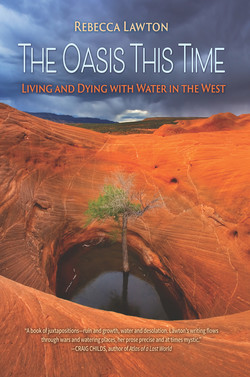

Читать книгу The Oasis This Time - Rebecca Lawton - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2.

SEND IN THE CLOWNS

Chaos and order, yin and yang, Abbott and Costello.

—Joe Lee, author, cartoonist, and student

of the former Ringling Brothers and Barnum

& Bailey Clown College in Sarasota, Florida

MY FIRST VISIT TO LAS VEGAS: AN OVERNIGHT WITH MY mother, father, and siblings on a road trip home from Arizona. We’d hauled across three states in our old Chevy station wagon, my father driving, my mother navigating. We four kids crowded into the backseat, maybe one of us in the seatless way back. It had been a wandering break from our home in rainy Oregon, the kind of trip we all loved. We’d milked the best out of every campground we’d found in the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts, often dry camping where no one else had pulled off. The nights sparkled with stars. The songs of coyote packs edged the dark. While our folks slept on a plywood bed in the wagon, we kids lay out under a shelter of sky, with only the thin layers of well-worn cotton sleeping bags between us and the godforsaken wilderness. They were more than enough.

When we entered Las Vegas’s orbit, we were still in thrall of the natural wonders of the Grand Canyon. We’d gotten dusty in mining and farming towns. We’d hung out on wooden porches in Old Tucson, were right there when outlaws challenged each other in the dirt streets. By contrast, the city had the shimmer of mirage. A fantasy of flickering lights—at first beckoning, but then proving hard and gray and dirty with littered streets.

We stayed less than twenty-four hours, arriving at dusk one day and leaving after breakfast the next. I remember just one, vivid episode during that small window of time. Our family of six was returning to our motel room via a concrete alleyway. My folks were out in front of us kids. Maybe we had our shoulders hunched to the chaos. Maybe we’d just left a 1960s version of today’s All-You-Can-Eat casino dinner. For sure we got a good look at the unglamorous posteriors of businesses backed onto the alley. Only a few other tourists walked there, hurrying past, dressed up for the foreign landscape in suits and heels. Slot machines jingled and whirled wherever a casino door stood open. The sounds matched the strangeness of the sights.

Down the alley, far toward the end, a man worked the sidewalk with a wide broom. Even from a distance, I could tell he wore some kind of costume. From billboards, I’d gathered that Las Vegas traded in disguise—women in jewels and feathers, adults with mask-like faces wearing perpetually excited looks as they watched outpourings of coins from slot machines. I stayed behind my parents and close to my older siblings—for once my place as third child didn’t bother me. We strolled nearer the sweeper. As we came into range, I stole the inevitable look. He was a sad-faced clown. He wore a suit of rags, battered derby, oversized tie, and big, floppy shoes.

He kept complete focus on his work. His alley-sweeping was not a performance. If not that, then what was it? He was really cleaning up. Maybe even the janitors were part of the act in this strange, out-of-place place in the middle of the Nevada desert.

WHAT HAPPENS HERE, STAYS HERE. IT’S THE LAS VEGAS CREED, a promise of anonymity for the visitor. The slogan is world renowned, the place considered a port in any storm. In the 1990s, the city had billed itself as a family-friendly destination, but that tack just didn’t cut it. Kids weren’t proving to be the big-ticket customers that their adult gambling counterparts could be. A casino host puts it this way: “I have a guy go to the pool and dump like seventy-eight thousand dollars in three minutes. He didn’t win a hand. It was brutal, right?” Meanwhile dads and moms, out of necessity, might dodge any come-ons as they shepherd the kids to the discounted buffet.

“Las Vegas needed a new direction,” the advertising agency R&R wrote in 2002 for the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, “for positioning the brand that would tap into the visceral and deeply emotional reasons visitors connect with the city.”

How visceral? No less than the fundamentally American entitlement to independence. How emotional? Our very need for liberty. Drawing on “rigorous brand research and analytics,” R&R concluded that people come to Las Vegas yearning to breathe free. “Adults get tired of adulting from time to time and desperately need some ‘Adult Freedom’—in a place where they won’t be judged.” In Las Vegas, one’s conduct needed to be off the record. The campaigners called the new spin a code, insight, tagline, cause, message, cultural phrase, platform, voice, spark, strategy—by any other name, it was branding. A business proposition.

It worked. R&R’s campaign and tagline entered the fabric of American culture, went worldwide, and “produced some of the most celebrated work in all of advertising.” The Visitors Authority saw a seventeen-to-one return on advertising dollars; year-round hotel occupancy rate boosted to eighty-seven percent, twenty-two percent above the national average; doubling of annual visitation from about twenty-one million guests in the kiddie era to forty-two million in 2016. Recognition in the media. “A stroke of marketing genius” (The New York Times). “A cultural phenomenon” (Advertising Age).

Uniforms for staff at most casinos morphed from those of dirndled, kid-friendly storybook characters to bikini tops and tight, revealing pirate’s pantaloons. Money and water flowed on the four-plus-mile reach of boulevard known as The Strip with a newfound sense of abundance. Families still could find plenty to do, but mostly at Circus Circus, which continued to flash the face of Lucky the Clown on its neon marquee. Fodor’s Travel dubbed the Circus Circus Adventuredome as “a welcome oasis in the frenzied Vegas adult scene.” Otherwise, Las Vegas itself became known as a rest stop away from the demands of parenting, running a household, working nine-to-five, and otherwise grinding on the wheel of daily obligation.

A FRIEND I’LL CALL MIKE RECENTLY SHARED THE STORY OF the power of Las Vegas to lure grownups into its cool embrace. Mike’s father, “Richard,” had reached his nineties after serving in the public sector, retiring in a wealthy suburb of Los Angeles, and inheriting a fortune in California real estate from parents and siblings. Richard also had acquired three marriages over the years: the first to Mike’s mother (ending in divorce), the second to a successful, working wife (lasting until her death), and the third to a much-younger, struggling single mother.

When I met Richard in his eighties, he walked with a limp and the uneven posture of a man suffering from scoliosis. He was quiet, mostly listening during conversation and responding with few words. He did have alive, interested eyes. When Mike saw him at his ninetieth birthday party in Los Angeles, though, Richard had become homebound. There was no more talk of the world travel he’d done with his third wife, “Annie.” Instead, the age gap between them had grown too wide to cross.

“One night Annie called me,” Mike says, “and was kind of hysterical, saying that Dad was in the hospital doing really, really badly, and was in Las Vegas. She said, ‘I’m giving you a chance to see your father’ before he dies.” Mike felt the sting of her words but wasn’t surprised. Annie had become Richard’s gatekeeper in recent years. Gradually, with a little-girl voice and manner that Mike describes as timid, she’d encouraged Richard to bond with her daughters and their string of live-in boyfriends.

Still, Mike wanted to see his father. He arranged a flight the next day to Las Vegas. Annie called in the morning to say he was too late. Richard had passed in the night.

“Yeah, thanks,” Mike recalls thinking, “but what were the circumstances of his death? What was he even doing in Vegas? Why would anyone load a ninety-something man that frail into a car to drive him all that way?”

Mike still doesn’t know, but he suspects it had something to do with Annie’s own addiction to Glitter Gulch. She’d often flown to Las Vegas to see a good friend there during her marriage to Richard. “Here’s Annie, my age or younger, and Dad’s an old man. I’d suspected some sort of romance, because she’d take off and go there alone. Maybe Dad even knew about it and was okay with it.”

At Richard’s wake, Mike met the “friend,” a private contractor who worked for several casinos. “His job was to keep their best customers happy. He’d give gamblers little tchotchkes and a free meal here and there and make them feel like they’re big shots. Basically he was paid to build people like Annie up. It began to dawn on me that she’d been going to Vegas to gamble, and was probably gambling away all of Dad’s wealth. She led kind of a double life.”

Mike finds it ironic that Richard had been in Vegas at all. “He was very anti-gambling. There was some story about his own father betting away what little money he had. Dad wasn’t one of those people who ‘goes to Vegas.’ He thought it was stupid. He never wanted to go.”

I KNOW SOMETHING ABOUT ADULT FREEDOM. THE GRAND Canyon river trips I worked in the 1970s and ’80s took people out of their day-to-day and into a different world—a deep, barely accessible place both physically and in the realm of regular human experience. The few dozen or so passengers on every trip unwound as they never did on the other rivers I worked in four other states. The letting go wasn’t something prescribed by river management. You couldn’t read about it in the advertising. Several days into a trip, someone might say, “This wasn’t mentioned in your company’s brochure.” The unbinding of souls came from an authentic immersion into a mile-deep place with astounding sights, monumental whitewater, rock walls so tall they inspired constant awe, and desert nights of unequaled tranquility. The physical factors combined, basically, to enchant everyone who made the trek. Bonding was inevitable, born of beauty as well as a feeling of hard-earned accomplishment in getting to camp safely at the end of every day. It took teamwork to make our way through that big, honking gorge, no matter how many times we’d run it.

River canyons, especially the Grand Canyon, are places of secrets, too: hidden green grottoes never dreamed of by the sun-dazed visitor who spends the obligatory ten minutes at the South Rim; unexpected friendships, cemented by the cooperation needed to get down 224 miles of world-class wild river.

Once back in the real world, we didn’t talk much about how a trip had gone. There were the usual disclosures about screwed-up or aced runs through rapids, but other trip descriptions fell short. Not so much because we wanted to keep it quiet as to acknowledge that words could never do the place or the people justice. We could take a stab at describing the chiaroscuroed walls, the complete immersion into a natural wonder, the kick-ass waves produced by changing debris fans and inscrutable gneiss narrows, but we couldn’t explain how we’d been changed. We just knew that the place cast a spell. We’d been to a dwelling of solace and sanctuary, and we wanted to return again and again.

SOMETIMES ON THE GRAND CANYON TRIPS, A GUIDE OR PASsenger had to hike out—to go back to a job somewhere, to end the season and return to school, to resupply something very important, like toilet paper or wound sutures or beer. In that case, usually still in summer’s doggiest days, it was a grueling journey to the rim. A race with the sun. The hiker would start before daylight, carrying all the filtered river water he could manage. For his own sake, he’d have to get out before most tourists at the rim rose for breakfast. A hiker had to zoom up the Bright Angel Trail to the Devil’s Corkscrew (a wall of switchbacks near the top) with as little dehydration drama as possible. He’d bolt the 6.3 miles up to Indian Garden, where clean water was available to fortify him for the remaining 1.2 miles to the rim. “Indian Garden is an oasis in the canyon used by Native Americans up to modern times,” the National Park Service writes. The garden makes Bright Angel Trail the safest of all possible hiking routes from the canyon, due to “potable water, regular shade, and emergency phones.”

Going from an oasis like Indian Garden to an oasis like South Rim isn’t just a hiker’s invention; water sources on desert treks have been key to human evolution since our very first years. The earliest people lived and hunted in arid lands, traveling between rare springs and pools where plant sources of food grew and wildlife foraged and stalked. Anthropological digs of Homo sapiens in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, included paleontological evidence of isolated oases. Our forebears lived on the rare freshwater body, then traveled to the next one, especially during wet years, ultimately finding their way out of Africa.

Oases likewise determined the trajectory of trade routes and settlement sites. The 4,600-mile Silk Road through Africa, Asia, and Europe strung together water sources leading to and from communities like Turpan in China and Samarkand in Uzbekistan. There was the Darb el-Arba‘in camel route in middle Egypt and the Sudan. The Moroccan caravan path from the Niger to Tangier. The aboriginal foot trails in the Mojave Desert in the American Southwest. Separate bodies of water, sometimes miniscule, connected us.

Later, the built world borrowed key ingredients of the oasis to bolster community life. The water creed in Rome, In Aqua Sanitas, promoted immersion for recuperation, rejuvenation, and improved citizenship. Be a good Roman. Clean up and calm down in the baths. Elaborate systems of aqueducts led from rivers and springs to towns and villages to fill the balneae (small-scale public and private baths) and thermae (large-scale, Imperial baths). In these community centers of their time, citizens gathered for conversation, soaks, and massage.

Water, central to restoring the human spirit, was already imported from the wilderness.

So water flows from the Grand Canyon to Las Vegas today. From one adult playground to another, from its Rocky Mountain headwaters to its impoundment at Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams, the Colorado River helps supply the immense human need to recuperate. In so harnessing the water flowing between stone walls, we see it not as a river. We’ve invented language for its incomparable need to go somewhere, and ours: flow regimes, bypass tunnels, turbines, releases, and cubic feet per second.

MY FAMILY PUT LAS VEGAS BEHIND US, BUT THE MYSTERY OF the alley-sweeping clown stayed with me. A puzzle. Clowns around the globe have evolved on a long and wandering trajectory from trickster to fool to star entertainers under the big top. Trickster comes from the French triche, from trichier, “to deceive.” Fool derives from the Latin foilis, for “bellows” or “windbag” (and, some say, “scrotum”). Trickster is the one who slaps; the fool is the one slapped. The clown does both, giving as good as he gets, surprising us when he first trips and falls like a doofus but then jumps up to demonstrate he’s the best bareback rider in three states.

The television clowns I’d known before that evening in Las Vegas showed little inhibition—they’d sob at the death of a flea. They’d shoot water from a flower. Their single handkerchief would grow to a laundry line. The inscrutable man in face paint might do anything at any moment. Decades after walking with my family down that alleyway, whenever I’d stop at the Hopi mesas between river trips, the dancing clowns in the pueblos would be there, in costume, under the hot sun. Families sat in surrounding seats, or stood on the walls looking down onto the dirt dance floor, watching. Sometimes quiet laughter would ripple through the audience, but whatever amused them flew over my head.

Now I think it was all about distraction. Obviously the clowns knew what they were doing—vying for the attention of serious dancers, making offers no one could refuse, playing to the crowd. While they sashayed seemingly without agenda among the other players, they were part of the act, and an important one. Throughout history, the key purpose of clowns has been to take our eyes off the ball. They spin straw into gold. They pull tricks out of a bottomless bag and then lift an umbrella and float out of sight. They exchange violent slaps and insults, then do that ridiculous thing of making sausage. We let ourselves be taken in. We’re complicit.

While we’re dazzled, they part us from our gold. We’re feeling good, not so attached to our cash. We don’t resist the gambler’s sleight of hand even though our higher selves know it’s there. In the words of Ecclesiastes 1:15, “The number of fools is infinite.” Or, as P. T. Barnum famously did not say, “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

WATER THERAPY SPREAD FROM ROME TO OTHER PARTS OF the built world. In going global, it acquired an international lexicon. Spa, Belgium, is synonymous with the soak. So is the bain in France, Toplice in Slovenia, Bad in Germany, fürdo in Hungary, città thermale in Italy. Early adopters of the Roman tradition didn’t have access to today’s research, which shows that heart-deep immersion for just ten minutes in a tank of eighty-six-degree Fahrenheit water improves the ability of blood, full of oxygen and nutrients, to perfuse the brain. Immersion may be billed as luxury, but its positive effects on neurological function make it more essential health benefit than extravagance. Soaking helps us think straight.

The enhancement of shade at any oasis is key, too, natural or not. We (and other mammals) need a two- or threefold increase in natural evaporation to survive the desert sun. We bake out there, unless we have canopy to cool our sweat so we can keep going. Our minds, especially, need to chill out, as our brains stay about thirty-two degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the rest of us. That brain fog we feel under hot sun beating down through cloudless skies isn’t imagined; it’s real and measurable. If we were to listen to our hot heads—our overheated brains—we’d cease walking to the next oasis. We’d perish out there, become a parody, emulate the crawling, ragged victims in the magazine cartoons.

To bring us immersion and shade, today’s spa towns install fountains and pools, plant trees brought in from exotic locales, and build dimly lit rooms to reimagine the shade of the natural oasis. The purpose: to help stimulate endorphins, morphinelike molecules associated with feelings of deep pleasure. Endorphins attach to “opiate” receptors in the body and brain. The forty-billion-dollar resort and spa industry, a fast-growing sector of leisure travel worldwide, knows about these feel-good results, and it’s not shy in using water to get them. Hot tubs, steam rooms, mud baths, and other assorted water bodies are built for relaxation, rejuvenation, and recovery. The touch of water on bare skin at the end of a hard day? It feels like heaven, and heaven is the oasis.

THE VALLEY DUBBED LAS VEGAS (“THE MEADOWS”) WAS known for its wealth of water long before the casinos offered Jacuzzi rooms alongside nickel slots with 93.42 percent odds (tops). “Oh! such water,” settler Oliver Pratt wrote in 1848. “It comes … like an oasis in the desert just at the termination of a fifty-mile stretch without a drop of water or spear of grass.” The Meadows has quenched human thirst for thirteen thousand years; it has sated wildlife for much longer. The natural artesian flow of the valley, though—once enough to “propel a grist mill with a dragger run of stones!” (exclamation mark courtesy of Pratt)—is a thing of the past.

The Meadows began desiccating in the 1800s with the advent of the railroad (steam engines needed a lot of H2O) and the 1905 formation of the Las Vegas Land and Water Company. Growth followed, then military and industrial development, then gambling, then Boulder Dam and “Lake” Mead to water it all. A steady rise in population followed in the 1940s and ’50s. About Las Vegas, the US Geological Survey writes in modern reports, “By 1962, the springs that had supported the Native Americans, and those who followed, were completely dry.”

To recapture the precious, natural oasis ecosystem that had once characterized The Meadows, those supplying Las Vegas with water perform a sleight of hand that fits the illusory quality of the place. The Colorado River, harnessed at the dam that hoovers water toward Mead, fulfills eighty-six percent of the valley’s water portfolio. Groundwater pumped from beneath the city and its sprawl supplies what the river cannot, contributing another ten percent to metropolitan and urban use. Recycled water makes up the last four percent. The Southern Nevada Water Authority estimates that casinos and resorts use an annual thirty-two thousand acre-feet of river water piped from Mead and four thousand acre-feet of groundwater from private wells (thirty-six thousand acre-feet in all, nearly twelve billion gallons).

With 603,000 residents within the city limits in the most recent census, and over two million in the greater metropolitan area—as well as forty-two million annual visitors brought in by successful advertising—the once-abundant surface and ground-water of the valley hasn’t met Last Vegas’s needs for years. Wells have been so systematically overdrawn that the water table has declined more than three hundred feet. The associated subsurface rock and soil, naturally hydrated when groundwater stays in the ground, has “deflated” and sunk some five feet in places. Resulting earthquakes, irreversible ground collapse, and property settling have caused billions of dollars worth of damage in the Las Vegas valley. Ground failures will worsen, says the US Geological Survey, as current use continues.

Far worse than any property damage is the sobering fact that, once depleted, groundwater won’t replenish for millennia. In the Las Vegas valley, natural recharge of the aquifer system—or replenishment from rainfall permeating the subsurface soil and rock—ranges from twenty-five thousand to thirty-five thousand acre-feet annually (only a quarter to a third of the more than one hundred thousand acre-feet or thirty-three billion gallons of subsurface water that we withdraw each year). That the water balance sheet is out of whack is not a new trend. In 1911, Nevada State Engineer W. M. Kearney advised against the region’s “lavish wasteful manner [with water], which has prevailed in the past.” Not many took him seriously.

Where does all the water go? Largely toward the creation of faux oases. The Water Authority estimates that sixty percent of drinking-quality water delivered to homes and businesses in Las Vegas irrigates landscaping and fills water features. In short, more than half of water that could be left in the river or under ground spews into fountains and onto lawns. Some seventy percent of residential use and twenty percent of casino and spa use is applied outdoors, for landscaping and swimming pools, or evaporated with the gusto of any arid region. Water use in Las Vegas is largely consumptive—that is, it’s fully used. It can’t be treated and recycled to bolster that measly four percent of recycled water (which is great for landscaping) or reserved for the river ecosystem in return-flow credits (conserved acre-feet that go back on the river’s side of the balance sheet). Consumptively used water is lost water.

So what? So Las Vegas is thirsty for more. The Water Authority is actively looking for new sources throughout Nevada. The US Geological Survey has said that piping water from the Virgin and Muddy Rivers to the north is a leading option for supplementing water-demand shortfalls in Vegas. Natural wetlands farther from The Meadows will be drained. Wetland species in remote reserves, like a species of tiny fish known as the Moapa dace, are already threatened by environmental changes that include drought. They hang on in little green refuges where one can stop to watch birds and wildlife, like the wetlands of the Desert National Wildlife Refuge Complex. If voracious Las Vegas has its way, such real oases may go dry.

And we play our part. We whose need for water is to this day lavish, we whose spirits soar at the sight of green in the desert, we who ooh and ahh at the miracle of fountains where no rain falls. Rather than steward and care for the oases nature gave us, we bask in the poolside shade of transplanted palms. Who among us doesn’t? We prefer efficiency to conservation—so say the water authorities—because the latter feels punitive.

We want to be free. We want to be distracted. We’re the Romans who smile and soak, play low-return games, and laugh when they send in the clowns.

MIKE’S FATHER RICHARD WAS BURIED IN A VETERAN’S CEMEtery outside of Las Vegas. In his final days, Richard had been reminiscing about his World War II service and may have even requested the honor guard that he’d earned. He’d flown C-47 supply planes in Burma at the time when airmen were crossing “The Hump” over the Himalayas from India to China without navigation systems. Taking inordinate risks, routinely pushing aircraft rated for eighteen thousand feet another ten thousand higher, the soft-spoken Richard had been a badass pilot at age twenty.

Even so, Mike found the military funeral surreal. “There were the marines and their starched, stiff outfits. They folded the flag and took it to The Widow, as she was called, and then saluted her. It reminded me of John F. Kennedy’s tribute or something.” Most of Richard’s surviving friends were hundreds of miles away in Los Angeles and too elderly to travel. All the other attendees were Annie’s family and friends. Of the elegies read, only Mike’s described a Richard from a different time and place. “I concentrated on the father I knew growing up.”

Richard’s resting place lacks anything wet. “It’s very modern, with flat plaques right on the ground. There aren’t gravestones or anything. There are just markers on concrete and no greenery anywhere. And it’s 110 degrees.” Not the emerald fields of Arlington or Golden Gate National Cemetery. Richard probably hadn’t dared to hope for a long life in those heady days of transporting explosives over too-high mountain passes guided only by the sun and stars. Now his gravesite roasts under unrelenting sun, at a concrete cemetery that he wouldn’t have chosen on a bet, had he been a gambling man.

As Mike was leaving Las Vegas, he helped a friend of Annie’s with her bags at the airport. “Jean and I were standing in line outside the terminal when a taxi pulled to the curb. A woman literally fell out of the car. She was dolled up, but her makeup was all streaked. She’d obviously stayed up all night gambling. I’ve never seen anyone so drunk in my life.” The woman cut in front of Mike and Jean in line. “Jean spoke up, saying that we’d been at a funeral. The drunk started swearing and bitching. ‘I don’t give a fuck about your funeral, I’ve had a really bad week.’ I realized that she’d probably lost everything gambling. And this whole scene just summed up the sadness of the place. That really capped it for me. Farewell to Vegas.”

Mike hasn’t been back. “Vegas is supposed to be this big, decadent party place, but it’s so depressing. People like this drunk woman go home broke. It’s not like anybody’s really having fun.”

He lost touch with Annie, who worked quickly to consolidate her husband’s multi-million dollar estate. Mike did consult with a lawyer and had asked his father in earlier years about some valuable family properties that predated Annie and even Richard. In the end, though, Mike’s soft-spoken accountant father either failed to act or did so passively: he didn’t write a will or trust. All his wealth went to Annie—or rather to Las Vegas, where she now lives and, Mike believes, gambles. Her short jaunts to the escape of an adult playground became one long trip.

He is mostly contemplative about it. “She was always so meek and nervous around me, but clearly she had this other side. She wanted to be treated like a queen, in the casino’s VIP lines and such. They’re just these phony preferences, though, and she can’t see through it.”

Mike grieves his father and his strange end. “What’s awful is that Dad’s soul has to bake in a hell like that. But there he is.”

AND THERE WE FOUR KIDS WERE, IN A LAS VEGAS ALLEY WITH our folks, coming closer to an ill-dressed clown sweeping concrete. Panic grew in me. Clearly we wouldn’t be getting away without at least making eye contact. He saw the six of us and stopped working. My skin prickled with caution. Nevertheless we all gathered around this man who looked nothing like Bozo or Ronald but instead like the itinerant men we’d seen in trainyards, raggedy transients our family had dubbed “H. O. Boes.” The word homeless hadn’t yet entered our vocabulary.

My ever-outgoing father asked him, “Aren’t you Emmett Kelly?”

“I am.” The clown leaned on his broom and took us all in. His eyes sparkled from a face coated in makeup.

My father and Mr. Kelly shook hands like old friends. In a way, they were. Dad had known of Emmett Kelly Sr.’s circus acts in the thirties. He’d even seen Mr. Kelly’s character Weary Willie play for laughs at a time when they were as rare as hundred dollar bills. An existential clown, or tramp clown like Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, Mr. Kelly Sr. had worked hard or hardly worked, did his best against entire armies, found beauty in fragile garden flowers. He often got the girl, even dressed in an arguably unattractive way: white lips to accentuate a frown, ashen whiskers, clothing that might’ve been fished out of a dumpster. And pushing a broom? Just part of the king-of-the-road lifestyle.

The clown in the alley, I learned later, was Emmett Kelly Jr., the son of the original. Either one would have been as big a celebrity as I’d ever met. At that moment, though, Mr. Kelly Jr. seemed like a regular guy. He’d been acting the janitor, and I knew at least one other like him—the custodian at my school—a man in the realm of the real. Mr. Kelly Jr. was in costume, but not in character. He turned a genuine spotlight of attention upon us for the few minutes we spoke. He wasn’t responsible for this fake-o town. He only worked here.

He warned us kids to “stay away from places like this.” He handed out postcards, signed with a fountain pen, according to my younger brother, who remembers everything.

When I reported to my third-grade class about My Spring Break in the Desert, I mentioned the ethereal beauty of the Grand Canyon. The painted movie sets in Old Tucson. The horses we’d ridden up a dry wash in Wickenburg—a rural landscape that felt to me like wilderness. I wowed my peers with talk of a mountain lion I’d seen, even though it lived behind glass at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. No one questioned any of these fantastical events until I mentioned Las Vegas and meeting a famous clown.

“Emmett Kelly was sweeping an alley?” my teacher asked. She didn’t say anything more, but her reproachful look spoke plenty.

I held up a postcard, evidence that I’d seen him. I didn’t have the words, though, to convey that he’d been working with the care of someone whose job it was to clean up after a show. At the moment of our meeting, he was no more part of an act than my family. Among artificial lights in a growing faux oasis, fed by elaborate waterworks irrigating a stopover in the desert where the ecotone was being turned to toast, Mr. Kelly Jr. was the real deal. He knew his craft by heart, learned from his father before him. He played his role alongside that old shapeshifter water, which poured through fountains and canals and sprinklers and spas to nourish the Las Vegas sleight of hand: let me separate you from your purse. He, however, was authentic to the core—as real as the river harnessed to liven the adult playground. As real as Mike’s father, the World War II pilot who is buried there.

I could tell. I was still a kid. I’d have known a phony when I saw one.