Читать книгу Addiction and Devotion in Early Modern England - Rebecca Lemon - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Scholarly Addiction in Doctor Faustus

Faustus, being of a naughty mind and otherwise addicted, applied not his studies, but took himself to other exercises.

—The English Faust Book

What does it mean to say, as The English Faust Book does in 1592, that Faustus is “addicted”? Faustus, it seems, should apply himself to the study of divinity but is otherwise inclined, embracing alternate fields as the infamous version of the legend by Christopher Marlowe depicts in detail. Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus opens with Faustus weighing the merits of divinity, a field in which he “profits,” “the fruitful plot of scholarism grac’d.”1 But his very talents snare him, for, “excelling all” his peers, he becomes “glutted” with “learning’s golden gifts” and begins to seek another form of scholarly sustenance, ultimately “surfeit[ing] upon cursed necromancy” (1.1.18, 24, 25).

If Faustus’s appetite for scholastic heights differs from narcotic addictions, his surfeit nevertheless resonates with modern notions of addiction as pathology. As Deborah Willis writes in her study of the play, “It is not hard to draw an analogy between Faustus’s evolving relationship to magic and modern narratives of addiction.”2 Marlowe’s play, she argues, anticipates modern, medical definitions of the addict in staging the diminishing will of the individual in the face of compulsive behavior. Yet early modern addiction, as this chapter will explore, also appears in Faustus and in a series of sixteenth-century tracts to be beneficial and even laudable. As a result of what could be called compulsive addiction, but which one might equally deem devotion or dedication, Faustus proves an able and talented scholar, adopting a profession for his “wit” and excelling in it (1.1.1–2, 11). He thus fulfills the Latin root of the word addīcere, which was discussed in the preface: in Roman law to addict was to bind someone to service or to affix or attach oneself to a person, party, or cause. In Latin writings more broadly the term “addict” came to connote giving oneself over, or dedicating oneself, to a master, lord, or a vocation. Following these Latin origins, sixteenth-century writers use “addict” to designate service, debt, dedication, and devotion. In chronicling scholarly pursuits, for example, early modern translations of Cicero and Seneca invoke addiction to help account for the devotion necessary to follow an academic path, as this chapter reveals. So, too, with Reformation theological texts from Jean Calvin through English reformers such as John Foxe and William Perkins, in which addiction signals the state of deep dedication and surrender through which the believer receives grace.

Marlowe attended Cambridge at the height of the controversy over Calvinist theology, and his reaction to his education deeply marks his play.3 In exploring the influence of Calvin and Calvinist-minded Cambridge divines on Marlowe, scholars have debated the play’s staging of the doctrine of predestination and election, asking whether Faustus’s damnation serves as a warning for spectators or a critique of Calvinist determinism.4 Reading the play as a drama about election (whether or not it endorses Calvinist theology) proves challenging, however, because as Alan Sinfield has noted, “The predestinarian and free will readings of Faustus … obstruct, entangle, and choke each other.”5 The play does not make its representation of reprobation or election clear, but instead elusively hints at and refuses to resolve this question.

Given the play’s provocative but at times contradictory presentation of theological doctrine, it is worth considering the question of free will and determinism from a different vantage point. As the following pages will explore, the Calvinism of Marlowe’s education proves useful because it illuminates not only the theological influences on his play but also, more broadly, how he might have understood the nature of scholastic and theological commitment itself. Calvin, like his English followers Perkins and Foxe, outlines the doctrine of predestination and election through reference to—and celebration of—a single-minded devotion deemed addiction.6 Faustus is, in line with this form of devotion, addicted to study, giving himself entirely to his chosen field: he signs a legal contract, professes his dedication, and exclusively commits himself to his studies. Marlowe stages scholastic devotion as a laudable addiction, drawing on classical and Christian evocations of the term, even as Faustus’s choice of necromancy illuminates one of the dangers of such devotion: attachment to the wrong faith or field. Marlowe’s Calvinist contemporaries acknowledge precisely this danger, suggesting how the surrender and release associated with addiction, while potentially saving, can lead to damnation when directed to the wrong spirits or forces. Thus, one might be addicted to sin or carnal pleasures, or more frequently, suffer from addiction to idolatry and popery, a condition Calvin writes of enduring before his conversion by God.

Tracing the invocations of addiction in the theological writings influential to Marlowe, this chapter thus approaches Doctor Faustus not as a drama of election but as one about the challenge of commitment. In drawing on and questioning contemporary invocations of addiction, Marlowe stages Faustus’s perilous attachment to bad religion while never condemning his title character for his devotional aptitude in the first place. The tension of the play lies precisely in how Faustus’s devotion and surrender to necromancy might have signaled his predisposition to what his contemporaries deemed a positive addiction, namely to God. To condemn Faustus’s constancy to Mephastophilis, or to necromancy more generally, disregards the very predisposition for addiction that might have led him to God, for it is Faustus’s paradoxical willingness to forego the exercise of free will, and his resolve to release into the supernatural, that marks him as open to receiving grace. His dedicated resolve might have flourished in the proper direction, as the play’s epilogue notes—Faustus might have “grown full straight” (epilogue). Instead, he follows magic—and as a result, the moralizing voice of the chorus attempts to frame Faustus’s path as pathological or sinful, deeming him a glutton who surfeits on necromancy.

Yet the play vigorously depicts Faustus’s relation to magic as a sign not of his compulsive appetite, but of his scholarly drive.7 Even as the Chorus warns that Faustus serves as an emblem, an Icarus burned by magic or a fierce God, the play itself stages a different (albeit related) drama, one not preoccupied with magic—after all, Faustus’s magic tricks have proved disappointing to generations of audiences—but with the struggle inherent to devotion. Overpowering dedication, and the individual release of oneself to an external force, is at once necessary, dangerous, and potentially pathological. If to early modern writers such surrender is often laudable and desirable, Marlowe, through Faustus, pushes early modern conceptions by staging both the wonder and terror of addictive release. That grace might enter in the form of the devil proves the play’s most haunting challenge to Calvinist invocations of addiction. The drama of addiction thus hinges on the longing for, yet also the regret surrounding, true faith, as Faustus finds himself—through the very process that might have offered salvation—contractually bound to hellish companions instead.

Addicted to Study

Tracking the first appearances of the term “addiction” in English reveals its use in two contexts: classical study and Reformed theology. Early modern translations of Cicero and Seneca both evoke addiction to study as a positive pursuit. In Cicero’s A panoplie of epistles (1576), as translated by Abraham Flemming, he recounts fondly the “knowledge, learning, and exercises, whereunto from my childehoode I haue béen addicted.”8 The Latin original (“iis studiis eaque doctrina, cui me a pueritia dedi”) deploys the term “dedication,” signaling that the early modern translator found “addiction” an adequate cognate. Further epistles underscore Cicero’s attachment to study as a form of addiction. Writing of the “study, to which I was addicted,” Cicero calls scholarship the “letters to which I have ever been addicted.”9 Addiction here signals sustained attachment and devotion, as Cicero expresses his commitment to his course of study and his singular application of his talents. Cicero’s son seems to have inherited, or reproduced, this addiction to study, at least according to a letter to Cicero from Trebonius, who, on seeing Cicero’s son in Athens, reported him to be “a yong man addicted to the best kinde of studie …, and of a passing good reporte of modesty: which thing, what pleasure it ministred unto me, you may wel understand.”10

Seneca, too, describes study as a form of addiction. In the translation by Thomas Lodge, The workes of Lucius Annaeus Seneca, both morrall and natural (1614), the young philosopher pursues his studies, as Faustus himself does, against the wishes of his family: he “addicted himselfe to Philosophie with earnest endeuor, and vertue ravished his most excellent wit, although his father were against it.”11 Just as Faustus challenges the promptings of his professors with his “wit” and finds ravishment in his studies, so too does Seneca (1.1.6, 111). Indeed both descriptions employ the term “ravish” to describe an intense relationship to a field of study. In doing so they suggest the force of scholarship in overwhelming, transporting, or capturing the scholar. Faustus, like Seneca, is carried away, but willingly and pleasurably. For both, the tension between family and worldly concerns, on the one hand, and the dedication to study, on the other, structures their understanding of vocation, further illuminating the exclusivity and captivation of addiction: “I will wholly dedicate my selfe, and … I will addict my selfe unto studie. Thou must not expect till thou have leasure to follow Philosophie. Thou must contemne all other things, to be always with her.”12 This exclusivity—condemning other pursuits for one’s field—separates addiction from mere instruction. Seneca rejects other intellectual, and presumably familial, lures in favor of a singular relation to philosophy. Faustus, too, models such dedication. “I wonder what’s become of Faustus, that was wont to make our schools ring with sic probo,” his friends demand (1.2.1–2). He retreats into necromancy, dismissing, as the opening soliloquy dramatizes, all other fields. Addiction to study is an extreme form of dedication and requires one to clear away all other obligations.

Addiction, as deployed in these early modern classical translations, is a crucial component of scholarship: only with clarity and dedication can the philosopher find his calling. Furthermore, addiction represents a process of culling away rival pressures, be they worldly or even intellectual. Lodge’s translation of Seneca’s essay “The Tranquilitie and Peace of the Mind” reads, for example, “A multitude of bookes burtheneth and instructeth him not that learneth, and it is better for thee to addict thy selfe to few Authrs, then to wander amongst many.”13 Addiction as dedication stands in contrast to flighty, unfocused pursuits: “He then that hath all his commidities in their entyre, may stay in the hauen, and addict himselfe readily to good occupations, rather then make saile and to go and cast himselfe athwart the winds and waves.”14 The scholar is not, Seneca argues, an explorer visiting new ports. One cannot “wander,” but one must hone, cull, and focus. Committing to one location, one “haven,” the scholar studies deeply. Wide-ranging study is a burden and distraction. Better to “addict thy selfe to few Authrs.” So, too, with Faustus, who, in narrowing the available fields, announces he will “sound the depth” (1.1.2) to find a pursuit that will envelop or ravish him. He will “profess” his art, proving a “studious artisan” and a “sound magician” (1.1.2, 56, 63). From this vantage point of addiction, Faustus’s desire to “sound the depth” of his studies, and his interrogation of fields in search of the proper path, seems not fickle but ultimately focused. Rather than choosing necromancy out of a kind of boredom, as Kristen Poole argues—“his descent into the black arts at first seems to be the product of his intellectual ennui, as he searches for new challenges and intellectual heights”—he instead seeks his Senecan “haven.”15 While Poole’s phrase “intellectual ennui” aptly accounts for Faustus’s fear of death and stasis, which is evident in his condemnation of divinity as “hard” (1.1.40), nevertheless he dismisses certain forms of scholarship not out of exhaustion but because he seeks to immerse himself in a limitless field. He needs to aim at the unknown, the unseen, and the unachievable.

Addiction, then, is a particular form of scholarship—it involves commitment, focus, depth, and stillness. Of course, these authors also concede the dangers of such single-minded dedication. Seneca announces the dangerous power of addiction when he writes, for example, that one must be cautious in one’s pursuits: “For the minde being once mooued and shaken, is addicted to that whereby it is driven. The beginning of some things are in our power, but if they bee increased, they carie us away perforce, and suffer us not to returne backe: even as the bodies that fall head-long downeward, have no power to stay themselves.”16 Seneca teases out the complex relationship of surrender and free will in scholastic addiction. Initially, the addict exercises choice: in the beginning “some things are in our power.” One might choose one’s path, as Faustus does—he elects to practice necromancy over divinity. But, Seneca writes, once the mind heads in a certain direction, addiction can carry one away. Addicts “have no power to stay” themselves. Momentum threatens but also fuels the addicted mind. Once on a path, the scholar progresses along it, gains speed, and moves forward even against his or her own will. Thus addiction is at once desirable, since it provides the dedicated resolve that propels the scholar forward, and potentially dangerous, since the power of addiction pulls one along the chosen path, for good or ill. The title of a text by the lawyer William Fulbecke betrays this double link of addiction and study: A direction or preparatiue to the study of the lawe wherein is shewed, what things ought to be observed and used of them that are addicted to the study of the law, and what on the contrary part ought to be eschued and auoyded (London, 1600). If the pursuit of learning is admirable, then the deeper the devotion, the greater the addiction and the more accomplished the scholar proves. “Driven,” “carr [ied] away,” “fall[ing] head-long downward,” the scholar demonstrates a lack of control admirable and overwhelming at once.

Addicted to God

Why does the scholar choose one path and not another? Seneca suggests that scholarly addiction emerges from one’s choices: “The beginning of some things are in our power.” But Marlowe’s contemporaries would answer differently. Addiction—whether to divinity or necromancy, to scholarship or to sex—comes from predispositions that, at least in a post-Reformation Europe influenced by Calvin, come not from human will but from God’s.17

As with Seneca, Calvin praises addiction as a form of careful study, in this case not of philosophy but of scripture: “They are then apt to receive the grace of the Gospell, which not regarding any other delightes, do wholy addict themselves and their studies to the obtaining of the same.”18 Like Faustus, the believer dismisses all other fields and devotes himself to his chosen path. In the case of the Christian reader, the fruits of study lead to addiction to Christ: “Therfore no man shal ever go forward constantly in this office, save he, in whose heart the love of Christ shal so reigne, that forgetting himself, and addicting himself wholy unto him, he may overcome al impediments.”19 Followers of Christ “addict themselves unto him, so that they did acknowledge him to be that Messias.”20 Further, “those are truly gathered into Gods sheepefolde … addict themselves to Christ alone.”21 The singularity of the commitment is clear: one is addicted to Christ “alone” “wholly.” Moreover, addiction to God compels the believer to follow a path, eschewing individual thought or will in favor of discipleship. Calvin writes, “For whosoeuer doe simplye addict themselves to Christe, and doe not strive to adde anye thinge of their owne head to the Gospell, the true lyghte shall never fayle them.”22

Throughout his Latin writings, including the biblical commentaries and sermons that comprise the vast majority of his published works in England and on the continent, Calvin deploys the verb addīcere to designate godly devotion, writing “se totos addicunt” of these dedicated readers.23 These Latin commentaries appeared in multiple editions and translations in England and dominated university libraries to the degree that, as Philip Benedict notes, “by the last decades of the century, Calvin’s works had eclipsed those of all other theologians in the library inventories of Oxford and Cambridge students.”24 Further, the importance of the English translations of Calvin, in addition to the French and Latin editions also published in England, can hardly be overstated. Between 1570 and 1590, forty-three editions appeared: “No author would be as frequently printed in England over the course of the second half of the sixteenth century as Calvin,” Benedict continues.25 Bibliotheca Calviniana, the table of editions of Calvin by language, reveals the prominence of English editions within a European frame: they are second only to Latin and French (Calvin’s original languages) and far exceed German, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, and other European-language translations.26

To study Calvin’s invocation of addiction in these publications is to find comfort in addictive surrender: being singularly focused, at the expense of other beliefs and relationships, brings the potential for redemption. Calvin writes, “GOD in his mercie dealt so lovingly with his people, when he redeemed them, that is, that they being redeemed, should addict and vow them selues wholy to worship the aucthour of their salvation.”27 Ministers of the word “may addict & give themselves wholly to the Church, whereto they are appoynted.”28 This reflexive construction—Christ’s followers “addict themselves” or “give themselves” (se totos addicant & deuoueant) to him and his church—might seem to indicate will and agency on the part of the believer in choosing the addiction. And Calvin does encourage his readers and audiences to foster the complete devotion encapsulated in addiction: his sermons and biblical commentaries repeatedly admonish listeners and readers to pursue utter devotion. But ultimately, he argues, addiction speaks not to individual will but to God’s favor. Only those who are “disciples of God” can “addict themselves”; those who are “unapt to be taught” reject Christ: “It cannot be but that they shal addict themselves unto Christ, whosoeuer are the disciples of God, and that they are vnapt to bee taught of God who do reject Christ.”29 The appearance of a reflexive construction in his Latin and its English translation (“addict himself,” “addict themselves”) seems, on the one hand, to counsel the believer to prepare him or herself for grace: “he must doe his diligence.” On the other hand, to modern readers the reflexive nature of the construction may be misleading in implying the believer’s role in his own addiction, since the agency of addiction does not lie with the addicted believer but in God’s grace. In this chicken-and-egg construction, those who are unapt to be taught cannot be taught; those who reject Christ have been rejected.

Calvin’s language is subtle. His rhetoric suggests, at moments, a form of free will in which the believer might stray from addiction to Christ toward another, less laudable attachment: “They do corrupt the power of Christ, who are addicted to their belly and earthly thinges: hee sheweth what we ought to seeke in hym and for what cause we ought to seeke him.”30 We “are ofte withdrawn” into lusts, being “addicted to [our] belly and earthly things.”31 But, at the same time, he makes it clear that only God can “correct that disease” before one can act: “Because by reason of the grossenes of nature, we are always addicted unto earthly thinges, therefore he doth first correct that disease which is ingendered in us, before he sheweth what we must doe.”32 Once God cures, he “sheweth what we must do” and “sheweth what we aught to seeke in hym.” In other words, one cannot even see the right path until God cleanses the natural depravity evident in one’s misguided addictions. The dedicated mind, with its resolution, is an illusion. Addictions are signs of grace or reprobation that one does not control.

Calvin establishes, then, a complex relationship between the compulsion to follow Christ and the lure of material life. On one level, these desires are clearly opposed to one another since one’s addiction, be it to Christ or to worldly pleasure, indicates elect or reprobate status. But on another, more fundamental, level, Calvin acknowledges that everyone struggles with pure addiction. Even the most faithful wrestle with competing desires. He claims, “It is true that the faythfull them selues are never so wholly addicted to obey God, but that they are ofte withdrawne with sinfull lustes of the flesh.”33 One might aspire to be “wholly addicted” but might err. In other words, addiction to God and addiction to the belly are at once opposed and yet connected as two sites for devotion that might both hold the believer. The tension between these two opposed forms of addiction can be reconciled only by acknowledging the inevitability of one’s dependence on God’s will. Humans, Calvin implies, struggle with some form of addiction. It is just a question of whether abandonment to addiction leads one to or away from God. Through grace, one might be able to embrace as firmly as possible servitude and obedience to God. This form of service and addiction is uplifting. The strength of one’s embrace of this addiction, however, depends on God’s grace. Without such a gift, one struggles with the earthly appetites and compulsions shackling the human body to its baser nature. The resulting addictions represent debasing tyranny.

This dangerous aspect of addiction appears in the English translations of Calvin’s French sermons. In his Latin writings Calvin deploys the term addīcere routinely, and the English translation faithfully tracks the term, rendering it as “addiction,” as noted in the citations above. By contrast, sixteenth-century French lacks modern French’s addiction and dépendence. When Calvin attempts to describe the phenomenon of addiction, he turns to potential cognates in terms ranging from adonner to attacher to dedier. Yet his English translators reintroduce the term “addiction,” illuminating the absent presence of the concept in the French sermons. Translating adonner, a term that designates a willful giving over of oneself, Arthur Golding turns to the term “addiction”—but only in special circumstances. Calvin, for example, uses versions of the word adonner 206 times in his Sermons de M. Jean Calvin sur le livre de Job. In Golding’s sizeable English folio translation (produced in six discrete impressions between 1574 and 1584 and amounting to what Stam calls a “bestseller,” which “achieved a popularity beyond that of any other Calvin commentaries”), he translates adonner as “addiction” in only three cases, each describing a special instance of attachment.34 When Calvin writes, “Or nous ayant acquis si cherement, il ne faut pas que nous soyons plus adonnez à nous mesmes, mais que nous soyons du tout dediez à son service,” Golding translates it as “Hee hath purchased vs so dearly, we must no more be addicted to our selues, but be wholly dedicated to his service.”35 Further, Calvin writes, “Et pourtant ce n’est pas raison que doresenavant nous soyons plus adonnez à nous mesmes: mais qu’un chacun soit prest de se dedier pleinement au service de Dieu,” and the translation reads, “It is not meete that henceforth we shoulde be any more addicted to our selues, but every man should bee readie wholly to dedicate himselfe too the service of God.”36 If active, dedicated devotion to God is the praiseworthy goal, Calvin here also describes an improper form of donation or giving over, a form deemed addiction in English, as in Latin. In this English version, “addiction” and “dedication” appear as synonyms, used interchangeably—one should not be “addicted” to the wrong path but “dedicated” to the proper course—and at the same time indicate addiction as a potentially dangerous form of attachment. Addīcere, adonner, and “addiction” signal mistaken attachment to oneself and the world, even as this attachment might mirror a more desirable form of addiction to God.

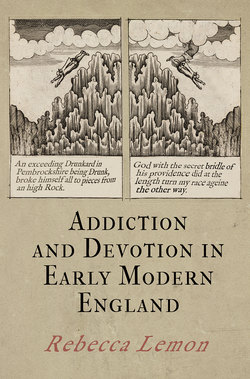

Calvin warns of the dangers of this improper addiction because he experienced them, at least according to his personal account of conversion. In the address to the reader prefacing his commentaries on the Psalms (first translated into English by Golding in 1571, following the Latin original published in Geneva in 1557 and French editions in 1558 and 1561), Calvin offers one of his few explicitly autobiographical statements about his conversion. He claims that he had been groomed for the ministry from a young age, but his father directed him to study law instead. While he endeavored to satisfy his father’s wishes, “God with the secret bridle of his providence did at the length turn my race ageine the other way,” toward divinity. Calvin relates how initially he “was more strictly addicted to the superstitions of the Papistrie, than I might with ease be drawn out of so deep a puddle.” His sudden conversion freed him from such bondage. God’s grace literally turned Calvin around, redirecting and reshaping him: God “sodenly turned my mind (which for my yeeres was over muche hardned) and made it easie to be taught.”37 Calvin here views himself as “strictly” or, in an alternate translation, “obstinately” addicted to the pope and superstitious belief.38 By “superstition” he indicates, as Alexandra Walsham notes, devotion to relics, saints, and other material manifestations of faith: “The ease with which the populace had been deceived by these tricks was itself a just punishment from God for its gullibility and natural addiction to ‘this most perverse kinde of superstition,’ and to a carnal religion that revolved around visible, physical things.”39 Here, Walsham’s terminology draws attention to the link between religious devotion and addiction. Only with God’s help to redirect and reshape him can Calvin relinquish his obstinate attachments: God did “turn my race” the right way: he “turned my mind” away from the papacy. God turns him around, softens his heart, and frees him from earthly lures so he can dedicate himself to the divine, a more compelling and liberating addiction.40 As a result, after his conversion he “burned with so great a desire of profiting: that although I did not quite give over all other studies, yet I followed them more coldly.”41

Calvin’s English followers, including Foxe and Perkins, take up and extend his model of addiction to scripture and superstition, continuing to tease out the depravity inherent in misguided addictions even as they trumpet the joys of addictive devotion to the divine. Foxe’s Actes and monuments (after the Bible, arguably the second most popular religious book in Elizabethan England following a 1572 government order requiring copies to be placed in all cathedrals in the country) invokes the devotional aspects of addiction when he narrates the lives of Protestant martyrs such as John Frith and William Tyndale, two figures who dedicated themselves to the study of scripture. These Reformed theologians demonstrate the addictive potential celebrated by Calvin himself. Frith, Foxe writes, “began hys study at Cambridge. In whose nature had planted being but a child maruelous instructions & love unto learning, whereunto he was addict. He had also a wonderful promptnes of wit & a ready capacitie to receaue and understand any thing, in so much that he seemed not to be sent unto learning, but also borne for the same purpose.”42 Like Seneca and Faustus, Frith has a “promptness of wit” and proves “addict,” “borne for” rather than merely acquiring learning.

Tyndale, too, proves addicted to study, which he pursues at Oxford, “where he by long continuance grewe up, and increased as well in the knowledge of tounges, and other liberall Artes, as especially in the knowledge of the Scriptures: wherunto his mind was singularly addicted.”43 Foxe praises the divine pursuits of Frith and Tyndale in terms that resonate with the scholastic addiction of Seneca and especially the devotional addiction of Calvin: these religious men are “singularly” focused, “borne” with aptitude and “turned” by God. Foxe also, and indeed more frequently, illuminates the dangers of addiction as expressed in mistaken attachments, especially when the believer proves addicted not to God but to Catholic idolatry: “These which addict themselves so devoutly to ye popes learning, were never earnestly afflicted in conscience, never humbled in spirite nor broken in hart, never entred into any serious feeling of Gods judgment, nor ever felt the strength of the law & of death.”44

Foxe’s contemporary, the Calvinist William Perkins—deemed by the end of the sixteenth century to be one of England’s most popular religious writers, with seventy-six editions of his work appearing before his death in 1602—also highlights the danger of Catholic attachments over devotion to God.45 “Perceived as translating Calvin for the masses,” as Poole puts it, Perkins praises those who “addict themselves unto Diuinitie,” yet cautions against the study of exegesis over scripture.46 He writes, “Hence come dissentions and errors into the schooles of the Prophets, which cannot be avoided while men leave the text of scripture & addict themselves so much to the writings of men, for thereby hee can more cunningly conuey strange conceits into mens minds: and therfore every one that would maintain the truth in purity and syncerity must labour painfully in the text.”47 The opposition of “purity and sincerity” to “error” and “dissentions” indicates the struggle of addiction. Perkins, even more pointedly than Seneca, explores how addiction to scholarship can go awry when the object of study is inappropriate.

Embracing Reformed theology, Perkins is particularly keen to encounter scripture directly. Study and translation of “the word of God” is the scholar’s appropriate calling. “The writings of men” only detract from the truth, and “popish writers” in particular lead audiences astray. Divinity students, he writes, “within this sixe or seven yeeres, divers have addicted themselves to studie Popish writers, and Monkish discourses, despising in the meane time the writing of those famous instruments and cleere lights, whom the Lord raised up for the raising and restoring of true religion, such as Luther, [and] Calvin.”48 Religious dedication, indeed dedication to God, is no longer enough; one must turn away from the Catholic version of God to celebrate that of Martin Luther, Calvin, and their followers. Reformed writings, like scripture, ring with “true religion,” “cleere lights” and purity. The copia of Erasmus must cede to the crystalline prose of Luther.

If Catholic writings corrupt the reader, only godly conversion cures. As Perkins puts it: “Againe, after conversion it is not an idle power in them: 1. Ioh. 3.9. He that is borne of God sinneth not, that is addicteth not himselfe, nor setteth himselfe to the practise of sinne; and the reason is given, because the seed of God remaineth in him.”49 Commitment to God and interest in worldly pleasures prove mutually exclusive. Perkins writes, “The love of the trueth, and of the world, the feare of the face of man, and the feare of God can never stand together. As also howe dangerous a thing it is to be addicted to the love of the world: for it hath beene alwaies the cause of revolt.”50 This is the power of addiction—it is a singular devotion that defines us, for good or ill. If Calvin understands abandoned devotion as a source of salvation as well as reprobation, then Foxe and Perkins more explicitly praise addiction to God in contrast to errant addiction to Catholic idolatry.

Finally, Marlowe’s contemporaries warn against necromancy itself as a form of addiction. In A dialogue of witches (1575), Lambert Daneau writes of addiction to Satan in these terms: “Whosoeuer were seruisable or addicted to Satan, were called by the name which is wel knowne and commune, that is Sorcerers,” who forged an “agréement with the diuel … & to be short, have wholy addicted them selves to Satan.”51 The active “agréement with the devil” proves, however, a form of ensnarement in which the sorcerer is victimized by the devil: they “fall into the snares of Satan, and become Sorcerers, that is to say, addicted unto Satan.”52 Condemning the sorcerer, Daneau includes a spirited call for another form of addiction, for if “the serpent is more addicted or subject to Satan, then the other beastes,” humans at least have the choice to turn away.53 Here the story of a convert who embraces Christ delivers Daneau’s point: “That he was converted to the fayth of Christ, it is read of him how earnestly and diligently he was addicted to that studie [of necromancy], which afterwarde, through the great goodnesse of god, he forsooke and renounced.”54 The parallels to Faustus are evident here. The scholar’s dedication, longing, and effort, directed initially to the wrong field, shift to worship of God instead, through whose goodness the convert is saved.

Addicted to Magic

If writers from Calvin to Foxe and Perkins insist on the double-edged quality of addiction as a firm commitment that may or may not lead to grace depending on the form of the devotion, Marlowe stages both the danger of choosing the wrong field and the struggle of committing in the first place. The play’s opening acts, from the first scene to the signing of the necromantic contract, chart Faustus’s devotional struggle as he seeks the addiction lauded from Seneca to Calvin to Perkins, hoping to lose himself in a vocation by relinquishing reason, soul, and body to a higher power. The play opens with Faustus, sitting in his study, surveying a range of scholastic pursuits and famously dismissing them all as inadequate to his purposes. In doing so he illuminates the challenge before him as he pursues a field of limitless endeavor. He wants to “level at the end of every art” (1.1.4, emphasis added), namely, aim at—but never reach—an end. Thus he condemns those fields that limit his striving. Logic, medicine, law, and divinity fail to attract his devotion because they result in a mere “end” rather than an imaginative expanse. While Aristotelian logic might have “ravish’d” him at one point, it now bores him: “Read no more: thou hast attain’d the end” of that field (1.1.6, 10). So, too, with medicine: “Why Faustus, hast thou not attain’d that end?” (1.1.18).55 These lines suggest the scholar’s desire to strive forward rather than to complete his studies. Law and divinity, too, limit his striving. Law “fits a mercenary drudge / Who aims at nothing but external trash,” while divinity, also, offers apparent certainty: “we must sin, / And so consequently die. / Ay, we must die, an everlasting death” (1.1.34–35, 45–47). If the audience might recognize divinity as offering unlimited grace (as the scriptural passage he reads goes on to promise), to Faustus its end in “everlasting death” mirrors the finality and nearsighted “aims” of other fields.

Faustus wants “to live eternally”; as Seneca writes, he wants “to be always with” the field of choice, perpetually moving forward so that, as Faustus puts it, “being dead” he might be raised “to life again” (1.1.24, 25). If these lines seem blasphemous—he desires, after all, to raise the dead in the manner of Jesus—they also speak to his desire for scholarship to offer him an unending path for life. Of course, as Genevieve Guenther argues, Faustus seems to crave a resolutely material life, seeking not everlasting salvation in heaven but instead life on earth, thereby making his comment doubly blasphemous.56 He wants to raise the dead back into their own bodies, she states, not into heavenly union. But what Guenther underplays, and what is notable in this opening soliloquy, is Faustus’s striving. His experience of embodiment is not static or fixed but mobile, for lack of curiosity or ambition is a kind of death, a mere “attain’d end” (1.1.18). By “end,” as Edward Snow argues, Faustus signals a “termination” rather than “an opening upon immanent horizons.” As a result, “having ‘attained’ [an] end means that he has arrived at the end of it, used it up, finished with it.”57 Magical texts, by contrast, allow him to imagine an unachievable, continually receding goal, a mystical form of knowledge just beyond his reach: it is “necromantic books” that “Faustus most desires,” for they are “heavenly” (1.1.51, 53, 51).58

Faustus ultimately choses necromancy because it offers not dominion but the ravishment of addiction: “’Tis magic, magic that hath ravish’d me” (1.1.111). The scholar seeks to be overcome and, as Calvin writes, “not regarding any other delightes,” to “wholy addict” himself and his “studies to the obtaining of” his goal.59 Even as Faustus wants to revel in “power,” “honor,” and “omnipotence,” he is fundamentally a “studious artisan” (1.1.55–57). Flourishing in his studies he hopes to be, as Cornelius promises, more consulted than the Delphic oracle. That is to say, he desires to be a source of knowledge that is invisible, empty, and devoid of will, reflecting instead the voice of the divine. This omphalos, or navel, of the world delivers its messages from a divine power that Faustus, too, wants to channel, “forgetting himself, and addicting himself wholy” as Calvin writes, so as to “ouercome al impediments.”60 Of course Faustus’s attraction to necromancy does not arise solely from his ambitious spiritual goals; as Luke Wilson has argued, he chooses necromancy with an expectation of its returns. He speaks of “gold,” “pearl,” “pleasant fruits,” and “princely delicates” (1.1.83–86). More specifically he seeks to command: necromancy offers servile spirits “to do whatever Faustus shall command” and to be “always obedient to my will.” “I’ll be a great emperor of the world,” he claims (1.3.37, 97, 104).

Yet scholars have tended to overlook how Faustus—perplexingly and contradictorily—seeks such power through the utter surrender of himself, releasing his own mind into a metaphysical, even divine, relationship. However much he might claim to pursue magic for material gain, his more sustained desire centers on metaphysical union. He seeks this merger through study, searching out the field that promises ravishment and then submitting himself to that field’s masters: Mephastophilis and Lucifer. Just as Calvin counsels ministers to “addict & give themselves wholly to the Church, whereto they are appointed,”61 so too does Faustus give himself: he “surrenders up to [Lucifer] his soul” (1.3.90). As with Calvin, Marlowe stages the complex exercise of the human will: Faustus strives and seeks, he labors in his field, but he must also surrender himself to it. Even as he proves eager to see if devils will obey him, and even as he celebrates his own skill in conjuring (“who would not be proficient in this art? / How pliant is this Mephastophilis, / Full of obedience and humility, such is the force of magic and my spells!”), ultimately Faustus “dedicates,” “surrenders,” and “give[s]” himself (1.3.28–31, 90, 103). On finding that Mephastophilis serves not himself but Lucifer, Faustus dedicates himself to Lucifer too; on finding his conjuration was per accidens rather than a sign of necromantic skill, Faustus responds not with disappointment but by pledging himself further: “There is no chief but only Beelzebub, / To whom Faustus doth dedicate himself” (1.3.58–59).

Faustus’s embrace of metaphysical merger appears in two ways: first, in his willingness to forego the logic he has mastered at the opening of the play, and second, in his signing of the contract.62 In choosing necromancy and binding himself to its masters, he exhibits the single-minded, exclusive attachment to his calling typical of the lauded addict: he follows faith (however dubious it might be). Aristotle’s logic and Ramus’s methods celebrate reasoning and critical thinking, but Faustus, despite his proficiency in logic and rhetoric, ignores such skills. Instead Faustus wants a “miracle,” he seeks to “be eterniz’d,” and to revel in “heavenly” books (1.1.9,15). This is not the ambition of a logician or lawyer. Imagination, emotion, hope, and faith, not logic, fuel his desires, arguably mirroring the devotion of the Christian faithful whose addiction to God defies earthly reason: “mine owne fantasy, / … will receive no object, for my head / But ruminates on necromantic skill” (1.1.104–6). A. N. Okerlund writes of these lines: “Faustus is telling us his mind is made up and not to be confused by critical analysis…. Distinguishing the valid from the invalid statement is the problem here—the problem to which Aristotle, Ramus, and their scholarly followers devoted their lives. But Faustus apparently cares not at all about the irreconcilable meanings of the Angels’ statements and hears only the words which excite his desires.” As Okerlund concludes, “Marlowe intends to call our attention to Faustus’s deliberate violation of formal logic.”63 While such a failure of logic might seem foolhardy, and indeed damnable, when viewed from the vantage point of addictive dedication Faustus’s illogical willingness to embrace magic appears as a sign of his faith: he refuses to be swayed from his path, in a manner Perkins himself might praise, by the writings of men. “We must no more,” Calvin writes, “be addicted to our selves, but be wholly dedicated.”64

If Faustus’s language of dedication, surrender, and ravishment—the language of addiction—expresses his scholarly ambition to lose himself in his studies, in surprising contrast (and throwing into high relief the scholar’s addictive devotion) Mephastophilis proves a cautious, reasoned, and even logical partner in magic. One finds reason and logic, for example, both in Mephastophilis’s answer to Faustus’s queries (he is, as many critics have noted, disarmingly straightforward in his answers) and in his effort to draw up the contract. Mephastophilis twice demands a “deed of gift” from Faustus (2.1.35, 60). The precision of Mephastophilis’s “deed of gift” is Marlowe’s addition to his source. In the English Faust Book, the term is “covenant,” which has greater resonance with biblical than English or continental law.65 Deploying a category of contract in the highly legal phrase “deed of gift” and emphasizing Mephastophilis’s logic rather than obfuscation, Marlowe creates a figure more sympathetic than the trickster of medieval mystery plays. At the same time, Marlowe draws heightened attention to Faustus’s failure—his inability to deduce or even hear the patently evident error of his choice.

Yet, Marlowe reveals, Faustus’s failure is also a triumph, for it exposes further his desire to addict himself to his field of choice precisely as Seneca and Calvin counsel. He embraces the contract as an opportunity to realize his addictive goals, constructing a document baffling in its terms but satisfying in its potential. This contract is another sign of Faustus’s longing for integration over autonomy, addiction over willpower. If Foxe, as noted above, derides those members of the early church who have “never entred into any serious feeling of Gods judgement, nor ever felt the strength of the law & of death,” Marlowe stages Faustus’s willing embrace of such deep feeling, encountering the strength of the law eagerly.66 For Faustus acknowledges that he will be proficient, indeed “great,” only to the extent he gives himself up entirely, donating his soul to another “as his own.” It is when Lucifer claims and owns Faustus’s soul that the magician merges with the devil he follows: “bind thy soul that at some certain day / Great Lucifer may claim it as his own, / And then be thou as great as Lucifer” (2.1.50–52). Far from shying away from such terms, Faustus designs them: he offers Mephastophilis his soul before the spirit has even requested the gift deed. In the play’s first act he tells Mephastophilis, “Go, bear these tidings to Lucifer: … Say he [Faustus] surrenders up to him his soul” (1.3.87–90). Then, in drawing up the contract’s terms in act 2, Mephastophilis’s request of “a certain day” (1.3.91) becomes, under Faustus’s design, “four and twenty years” (2.1.108), while the demand that he “bind [his] soul” (2.1.50) becomes Faustus’s more elaborate offering of “body and soul” (2.1.106) and further, “John Faustus, body and soul, flesh, blood, or goods” (2.1.110). In not just signing the contract but designing its terms, Faustus paradoxically wills away his will, resolving to surrender himself to the greater force of magic. Mephastophilis proves the beneficiary of Faustus’s longing for union and dissolution: “Had I as many souls as there be stars, / I’d give them all for Mephastophilis” (1.3.104).67

Contracted Faustus

Faustus’s contract is notable for its omissions as much as its guarantees. Indeed, the contract has generated significant critical discussion because its rewards for Faustus are so vague. Faustus appears, critics argue, to be unaware of how bad a bargain he constructs. In exchange for essentially two things—the ability to be a spirit and the service of Mephastophilis, both for twenty-four years—Faustus gives his body and soul to Lucifer. While the terms of the contract seem unfavorable to Faustus, it is nevertheless worth asking, what if the contract actually articulates precisely what Faustus seeks? In posing a version of this question, Guenther suggests that Faustus, in discounting the metaphysical realm, embraces the contract without recognizing its repercussions.68 But this chapter answers differently, by saying that if Faustus indeed seeks the devoted union he trumpets, he finds the contract a means of articulating this desire, if not securing it. Faustus’s ostensible goal—to be “great emperor of the world” (1.3.104)—cedes to his deeper aim, which is stated in the contract itself. Rather than securing his own “command” or empyreal power, he instead signs a contract ensuring that his own form will disappear and be supplemented by the continual presence of another. Indeed, he repeatedly insists that the contract include body and soul, even as Mephastophilis seems unconcerned with Faustus’s physical remains. Mephastophilis tells Faustus, “Thou hast given thy soul to Lucifer,” to which Faustus responds, “Ay, and the body too” (2.1.132–33). If his body and soul will be Lucifer’s after death, before that time Faustus will be physically joined to Mephastophilis, who will come—as the contract states—to Faustus “at all times” (2.1.103–4).

Forging a contract securing constant companionship with his magical mentor, on signing Faustus immediately asks (after first enquiring about the location of hell) to be married. He deflects his desire for a mate by claiming, “I am wanton and lascivious” (2.1.142), but this earthly request arguably tips his hand in betraying longing not for empyreal power but for union, precisely what the contract with Mephastophilis offers. Through marriage, as through magic, he seeks companionship on earth, to be overcome by relationship even as he also constructs a metaphysical union. The necromantic contract thus doubly satisfies Faustus, by offering him earthly company and spiritual merger: he enjoys Mephastophilis’s company for twenty-four years and then joins Lucifer, who elevates Faustus’s soul in claiming it as his own.69 For a character so ostensibly preoccupied with his own glory, Faustus proves surprisingly eager to lose himself in his field of study and devotion to the field’s masters. He seeks to be ravished, consumed, and overcome by the study of magic and the companionship of its practitioners. The contract’s terms thus illuminate the paradox of Faustus’s devotion: he is choosing to give up choice; he is exercising his right to surrender himself. Rather than seeking legal protection and securing his own claims, Faustus uses the contract to voice his loyalty, his surrender, and his willingness to give of himself to magic. Through the contract, in other words, Faustus attempts to announce, and secure, his addiction.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that Faustus takes the contract more seriously than anyone might reasonably expect. The legal scholar Richard Posner puzzles over Faustus’s “sanctity of contract,” exploring the numerous ways Faustus might have wiggled out of his obligation. First, the contract does not involve an immediate exchange but instead relies on Mephastophilis serving Faustus for twenty-four years before Faustus delivers his soul. “Such a contract,” Posner argues, “establishes a long-term relationship; and since not every contingency that might arise over a long period of time can be foreseen, it is understood that the parties will act in good faith to resolve problems as they arise rather than stand on the letter of the contract.”70 Even if Mephastophilis does exercise a “good faith” effort to fulfill every request, the contract remains riven with other weaknesses. As Posner writes, “The law refuses to enforce contracts that are against public policy, and a contract with the devil fits the bill.”71 If challenging the contract at the last moment would seem an unfair gain for Faustus, even here he could have nullified the bargain by offering restitution to the devil in the form of his body, his estate, and his service for the remaining years of his life, as the legal scholar Daniel Yeager argues in his analysis of the play.72 Faustus’s repudiation of the contract would be all the easier given the weakness of Mephastophilis’s position. The legal insistence of Mephastophilis that Faustus sign a contract in the first place might alert audiences—if not Faustus himself, who dismisses law as “too servile and illiberal” (1.1.36)—to the illegitimacy of his argument. “Mephostophilis’s insistence on formalities,” Yeager writes, “reveals his doubt about the validity of the contract.”73 Posner, too, concludes, “The devil could not argue either that he didn’t know that contracts with him were illegal or that the primary wrongdoer was not himself but Faustus…. So Faustus might have wiggled out of his contract after all.”74

Faustus does not seek, of course, to wiggle out of the contract. The question then becomes why Faustus upholds what Posner deems the “sanctity of contract” at all. Why believe the contract is, as Yeager writes of Faustus, “inviolable,” especially when Faustus has studied law and might recognize the legitimate challenges he could mount against Mephastophilis? He upholds the contract, this chapter answers, because this unmistakably legal exchange demonstrates the eagerness with which Faustus seeks—and perceives himself—to be bound. The issue is not, as Posner puts it, the “irrevocability of Faustus’s contract,” but rather Faustus’s perception and desire that his choice should be irrevocable. Once committed, Faustus remains convinced of the legitimacy of this commitment and strains to maintain his half of the bargain.75

If Faustus’s addiction were secure, surely neither he nor Mephastophilis would need a document signed in blood. But Faustus and Mephastophilis turn to these legal measures, one realizes as the play continues, because Faustus’s initial efforts to pursue addiction through willpower and resolve failed. At the start he repeatedly tells himself, “Be resolute” (1.3.14), reassuring Cornelius and Valdes of his commitment. When questioned by Valdes, who tells Faustus he can be a magician only “if learnèd Faustus be resolute,” Faustus responds, “Valdes, as resolute am I in this / As thou to live. Therefore object it not” (1.1.134, 135–36). Resolution to study and life go hand in hand for Faustus. As he conjures for the first time he again repeats: “Fear not, Faustus, but be resolute” (1.3.14). But resolve is not enough. Willpower alone cannot sustain Faustus in his commitment to magic. The contract represents, therefore, his second-order attempt to bind himself, offering more of himself than Mephastophilis demands. He designs a deed that will keep him dedicated to magic and overcome his hesitations. Logic ravished Faustus, as he admits at the opening of the play, and yet the scholar rejects this field anyway. He was resolved on divinity, until he was not.76 In embracing magic, in allowing himself to be ravished again, Faustus attempts to ensure his commitment through firmer means than he had exercised with his earlier devotions—hence, the contract’s specificity, and its insurance of his merger with Lucifer and Mephastophilis, not twenty-four years in the future but from the very moment of signing. And he must ensure (or at least attempt to secure) this continued obligation contractually because he knows what Seneca, Calvin, Foxe, and Perkins have illuminated before him: devotion is difficult.

If to some viewers Faustus’s failure to challenge the contract signals his reprobation (he literally cannot see what the audience is able to recognize—he’s making a terrible bargain in selling his soul to the devil), this chapter suggests how the play offers a more complex portrait of the hero than this answer allows. Faustus is not merely an emblem of Icarus, even if the Chorus might frame him this way. What makes Faustus’s situation at all sympathetic is his drive to devote himself to his studies, and through the contract he attempts to demonstrate—indeed, bloodily performs—precisely this devotion. Despite challenges to logic and reason, despite isolation from friends and distance from the heavens, Faustus binds himself to his field of study. The dilemma he faces—whether to commit himself to his path despite all of this evidence against it—is a compelling and inherently dramatic one not because it involves summoning the devil and being devoured by a hellmouth, but because it mirrors the travails of all aspiring addicts. Faustus wants to be bound, compelled, reshaped, and overcome by a metaphysical force. He seeks, as he repeatedly states, ravishment. While Faustus’s commitment to his contract might be, as Yeager calls it, “numbingly self-defeating,” Marlowe’s play illuminates, in this drama of self-defeat, the nature of attempted devotion.77 “Self” defeating might, in another context, be the precisely desirable outcome of devotion. The dissolution of the self in the supernatural is what the Christian faithful pray for and what the addict seeks. Indeed, even the bodily inscription warning Faustus away from the contract serves, arguably, to remind him of his desire for merger. When Faustus finds “Homo fuge” inscribed on his arm, he responds, “Whither shall I fly?” (2.1.77). This phrase of course refers to the biblical invocation, “man of god, flye,” from 1 Timothy 6:11.78 But one might also read “fuge” in its musical sense, which originated in the sixteenth century. A fugue, or fuga (out of fugere), is a form of composition weaving together two distinct threads contrapuntally. In this case, “fuge” resonates with Faustus’s broader desire to be subsumed or ravished by a greater power. Man, were he “fuge,” might turn into the music of the spheres. The word teasingly evokes an ideal, nonviolent form of union: just as the music emerges out of intertwining two strands of sound, producing harmony and depth, so too might Faustus be taken up into a relationship greater than himself.

Yet, tragically, in attempting union through a legal contract, Marlowe exposes Faustus’s desired but ultimately failed addiction. Like the Roman slave contractually bound to a master, Faustus becomes an addict through the law. But the addiction celebrated from Seneca to Calvin is not legal but vocational. It involves a calling. A contract upholds Faustus’s rights, even if they seem paltry. A contract can be negotiated and annulled, as Posner and Yeager note. One does not, by contrast, “wiggle out of” addiction. Thus, Faustus’s attempt to secure his addiction through contract exposes his devotional failure before he even begins. True devotion requires no contract, no promptings, and no threats. In the same way a beloved might erroneously hope a marriage contract could secure a lover’s fidelity, Faustus relies on the necromantic contract to fix his own insufficient desires.

Wavering Faustus

Faustus’s signing of the contract, ironically, betrays his own failed addiction. The document that secures his damnation fails to—and could never—represent his devotion. Certainly, the play’s remaining scenes offer the fulfillment of Mephastophilis’s promise: viewers see the rewards of necromancy in Faustus’s adventures. But as critics have long noted, the fruits of magic are rather slim. If Faustus hopes to command nations, he finds himself playing parlor tricks, leaving the audience, if not Faustus himself, disappointed.79 He mocks the pope and the horse-courser, he brings grapes to a duchess and conjures historical figures for the emperor and scholar friends. Why Marlowe, who stages Tamberlaine’s march across Europe and Asia, would hesitate to stage more satisfying magical triumphs has rightly preoccupied critics and audiences. The most evident answer, provided by the Chorus and ostensibly in concert with Calvinist theology and Elizabethan authorities, finds Faustus to be an emblem for misguided ambition. The failure of magic supports readings of the play as a cautionary tale (why sell one’s soul for mediocre magic?) insofar as one finds the play’s middle section to be an extended lesson on Faustus’s bad choice.

This chapter offers another answer, one—as suggested above—that finds the drama of the play to lie not in its subject matter of magic but, in properly Aristotelian fashion, in its action. For the drama of the play’s middle acts lies in Faustus’s wavering: the scholar with heroic resolve, a man who signed a contract he refuses to challenge, nonetheless falters. Indeed, perhaps more surprisingly than critics have noted, having made such a dramatic deal with the devil and having offered up his blood in signing, Faustus must nonetheless continually remind himself of his pledge. Faustus reassures himself, “Fear not, Faustus” (1.3.14). This imperative presages a series of reminders that Faustus offers himself as he wavers. “No go not backward. No, Faustus, be resolute. / Why waverest thou?” (2.1.6–7). This wavering, he claims, is because “something soundeth” in his ears, a voice that counsels, “Abjure this magic, turn to God again!” (2.1.7, 8). He keeps entertaining the possibility of repentance, or rather, the possibility of escape from his chosen commitment. In the first glimpse of the scholar after signing the contract, he cries, “When I behold the heavens then I repent” (2.3.1). Even though he might lament “my heart’s so harden’d I cannot repent,” he also actively embraces magic again on recalling the “ravishing sound” of the Ampion’s harp making “music with my Mephastophilis” (2.3.18, 29–30). He cries, “I am resolved: Faustus shall ne’er repent. / Come Mephastophilis, let us dispute again” (2.3.32–33). Wanting to dedicate himself entirely but pulling away, and wanting to repent but returning to magic, Faustus seems insecure in the very bargain he designed.

Faustus both picks the wrong field and can’t quite commit himself to it. For a man who begins the play wanting to be obliterated through integration into necromancy, he never achieves full surrender or release but instead wavers between professions and masters. He tells Charles V, “I am content to do whatever your Majesty shall command me” (4.1.15–16), and in doing so receives “a bounteous reward” (4.1.92–93); the Duke of Vanholt, too, tells him, “Follow us and receive your reward” (4.3.33). Even as he is bound to Mephastophilis and Lucifer, Faustus relates to earthly authorities as a pandering courtier seeking favor. He obsequiously calls Charles V “my gracious sovereign” while deeming himself “far inferior to the report men have published, and nothing answerable to the honor of your imperial Majesty” (4.1.12–14). Seeking favor and accepting rewards from earthly authorities, Faustus then relishes his power to humiliate his social equals or inferiors. The mocking knight and the horse-courser experience Faustus’s high jinx. These comic interludes strain against Faustus’s initial desire to be ravished, enveloped, and devoted: he seems preoccupied with his own status and reputation. Rather than dissolving his self, he seeks to protect and amplify it.

Fluctuating between authorities and erratic in his devotion, Faustus then begins to reproach others for his choices. As Poole writes, “Faustus has the unattractive habit of blaming others for his actions, often positioning himself as a passive entity.”80 He blames his own fall on reading: “Oh would / I had never seen Wittenberg, never read book” (5.2.19). Or, alternatively, he blames his fall on Mephastophilis, claiming he was tricked: “go accursed spirit to ugly hell: / ’Tis thou hast damn’d distressed Faustus’ soul” (2.3.77–78). Finally, Faustus claims that his relationship to Lucifer and Mephastophilis is incomplete, since he has not experienced magical power but only indulged his appetites. He, like the Chorus, condemns himself as a glutton, surfeiting on his desires: “The god thou serv’st is thine own appetite, / Wherein is fix’d the love of Belzebub” (2.1.11–12).81 He revels, he claims, in “a surfeit of deadly sin, that hath damned both body and soul” (5.2.10). He doesn’t even have the satisfaction of full, spiritual devotion to necromancy—it is his appetite that governed him, he claims, nothing else.

Finally Faustus calls out to God, in direct defiance of his contract: “Ah Christ, my Saviour, / Seek to save distressed Faustus’ soul!” (2.3.83–84). Having questioned faith but yearning for God, Faustus here proves a more complex and sympathetic character than the static scholars who fail him. Here he is not merely wavering—he wavers toward the divine, and in doing so admits the challenge of true faith. His prick of conscience, like the potential intervention of God in the form of the Good Angel or Old Man, teases the audience with hope for Faustus’s salvation. Indeed, for a Christian audience Faustus’s wavering toward repentance, while unrealized, is admirable, even heroic. The audience’s strong desire for Faustus’s conversion is modeled both by characters internal to the play and by the Chorus. Scholars cry, “God forbid!” (5.2.35) on learning of the contract, asking, “O what shall we do to save Faustus?” (5.2.46) and lamenting that the doctor had not turned to them earlier: “Why did not Faustus tell us of this before, that divines might have prayed for thee?” (5.2.40–41). The Good Angel, the Old Man, and the Scholars unite in attempting to sway Faustus back to salvation and devotion to God. They counsel Faustus, “Call on God” (5.2.26) even as the scholar understands it is too late.

Such wavering might demonstrate Faustus’s residual faith. Indeed, his necromantic addiction will always, one might argue, be compromised by his awareness—from his studies of theology and his emersion in Christian Wittenberg—of God’s divinity. Yet, at least to the extent Marlowe engages with Calvin’s theology, such mixing and mingling of Faustus’s devotions is as much troubling as hopeful. “No man shal ever go forward constantly in this office,” Calvin writes, “save he, in whose heart the love of Christ shal so reigne, that forgetting himself, and addicting himself wholy unto him, he may ouercome al impediments.”82 Calvin’s emphasis on exclusivity—the believer is constant, overcome, and subjected, while his love of Christ is entire, whole, and unfailing—precludes wavering. The faithful might be tempted, certainly: “The faythfull them selves are never so wholly addicted to obey God, but that they are ofte withdrawn with sinfull lustes of the flesh.”83 But Calvin clarifies that “ofte withdrawn” signifies not recantation but instead mere temptation, as the faithful remain steady in their dedicated service to God. For Calvin, all humans struggle with addiction: “By reason of the grossenes of nature, we are always addicted unto earthly thinges.” Nevertheless divine intervention might “correct that disease which is ingendered in us,” turning earthly into godly addiction.84 Marlowe, by contrast, depicts not conversion from one addiction to another but the incompleteness of attachment itself, whether to necromancy or to God.

If Calvin’s writings affirm the power of addiction to overcome the believer entirely, Marlowe instead stages—in his gnarled, questioning universe—a believer with an incomplete addiction. The play’s central conflict thus concerns Faustus’s attempt but ultimate inability to addict himself to supernatural forces. As he claims, “I do repent, and yet I do despair” (5.1.63). For even as Marlowe depicts the potential heroism of striving toward Christian conversion, he equally challenges it, by making repentance on Faustus’s part a form of spiritual and legal betrayal. For Faustus to reject the very path he surrenders to, by taking alternate advice and rejecting magic when its outcomes are insecure, would be to signal his infidelity to faith more generally, be it to the magic he embraces or to the God he does not. Tragically, then, even as Faustus’s wavering might be read as a sign of his potential for salvation, it nevertheless betrays his failed devotion not just to Mephastophilis and Lucifer but to anything: God, necromancy, friendship, or study of any kind. Staging the gap between the desire for addiction and its realization, the play illuminates how a character allegedly predestined for hell, overcome by desire for magic, and contractually bound to necromantic masters still cannot achieve addiction.

Yet in staging Faustus’s failure, Marlowe depicts not the depressing or powerless spectacle of the damned but the monumental difficulties of the addiction Calvin trumpets. Addiction, it turns out, is hard. If, as Rasmussen writes, “the central problem with most orthodox interpretations of Doctor Faustus is that they often verge on lack of sympathy, even open hostility,” viewing Faustus as a failed addict instead illuminates his wavering not as a sign of weakness but as indicative of the challenge of his task.85 Calvin sidesteps the effort necessary to achieve total surrender. Is addiction to faith really as simple as he makes it sound? Indeed, is addiction to sin that easy? Even as Calvin notes the ways in which the elect might stray from their addiction to God, he also describes addiction as effortless; it is simply a question of which addiction one might follow. Calvin’s theory, which is evident in his conversion story and his theory of election, seems to promise that addiction is everywhere—and more potently, that God is everywhere, as seen in all one’s addictive predispositions.86 But, Marlowe reveals, this theory of God’s dominant will falls short. If humans are so passive before this all-powerful God, then where is He? Mephastophilis works throughout the play to secure the soul of a character who is all too eager to give it away; God, by contrast, may or may not speak through the conscience, the Good Angel, or the Old Man.

It is perhaps perverse, then, that despite his inadequacies as a devotee, and despite his wavering, Faustus nevertheless reaches the promised end. He achieves final integration into Lucifer’s kingdom, and he does so not because of his own devotion but because of Mephastophilis’s extraordinary efforts. Again and again Lucifer and Mephastophilis counsel Faustus toward right belief, toward the kind of behavior expected of their “faithful.” Toward the end of the play, as Faustus tries to repent, Marlowe stages a divine figure literally holding the tongue and hands of the devotee, prohibiting him from straying: Faustus cries, “The devil draws in my tears…. O, he stays my tongue! I would lift up my hands, but see, they hold ’em, they hold ’em” (5.2.59–63). This staging of Faustus’s damnation, even as it shocks viewers, also arguably appeals to them.87 The fantasy of God accompanying the faithful through every hour of the day, staying their hands, holding their tongues, and distracting them with spectacles when they think of straying—this God exists only in reverse fantasy, in Marlowe’s play in the form of Lucifer. If even Faustus fails as an addict, despite receiving both direct encouragement from Mephastophilis and tangible material benefits from magic, imagine the challenges facing the godly. Tormented by popish regimes, ridiculed for restrained living, besieged by existential melancholy, and plagued by mortal questions, the godly must endure worldly troubles without a divine Mephastophilis by their side.

Conclusion

Marlowe’s play stages a supernatural universe in which even the unfaithful, weak, and wavering subject might meet his desired end. Understanding how Faustus’s addiction falls short illuminates the treacherous illusion of free will in the play. An attempt to exercise free will in defiance of his contract—indeed, the need to bind himself in a contract in the first place—reveals Faustus’s failure to lose himself in his devotional pursuit. The resulting opposition between free will (as it might allow him to turn from necromancy) and devotion (as it might demonstrate the fidelity of his commitments) is thus a Catch-22. Even as the evocation of free will might seem to dramatize Faustus’s potential to turn from sin, it also—to the degree that he successfully turns—demonstrates his propensity to infidelity and inconstancy, regardless of the devotional field. It is Faustus’s problematic inconstancy that signals his fall, as much as his failed exercise of what one might or might not take to be free will. Indeed, one might argue that Faustus should express even more commitment to Mephastophilis than he does, for only through this full exercise of addiction might he reveal his predisposition for true faith.

Rather than viewing the play as hinging on the tension between faith and free will—a tension that casts Faustus as either predetermined in his damnation or capable of saving himself—the study of addiction in Faustus illuminates instead the drama of his attempted devotion and his failed surrender. His desire to release his will to Mephastophilis indicates a predisposition to precisely the kind of radical faith required of the righteous believer; but his failure to achieve the form of commitment he trumpets indicates his fall. Viewed from this vantage point, the real question in the play is not whether Faustus has free will, but rather why Faustus has such a hard time committing. The answer suggested above is that devotion does not come easily. Even as the play illuminates the horrors of following the wrong path, it even more potently stages the challenge of, and fortitude necessary to, surrender to an addiction. Individual desires, combined with the external promptings of community, culture, and law, might still prove inadequate to the task. Faustus’s wavering exposes his incapacity for addiction, evident in his all-too-human propensity for wandering. After so many centuries, what remains admirable about Faustus is precisely his repeated attempts to give himself away to his pursuits in the face of his own fear and hesitation. This sort of addiction is clearly dangerous, but it is also extraordinary and compelling.