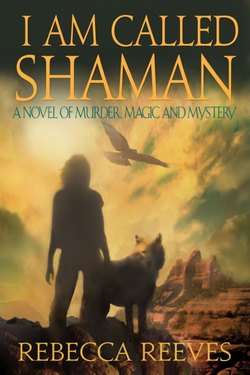

Читать книгу I Am Called Shaman - Rebecca Reeves - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Sunday, March 20

I sat on a stack of rough cut flagstone, and drew circles in the mortar dust with the toes of my pink-stained Reeboks. I tried to look as miserable as I felt.

My dad pointed a gloved finger at another pile of rocks we’d carried into the house this morning. “We need a piece of red sandstone next.”

“But I want to stay up here with you,” I said, placing the slab in his hand.

“School comes first, Abra.” His forehead furrowed as he concentrated on the exact placement of the rock that would become one of many in the new jigsaw puzzle fascia of the fireplace.

“It’s not fair.” I hated going to school with those cold cavernous rooms, fake lights, and hordes of unpredictable kids.

“I know it feels that way.” He sat back on his heels and gave me the smile he reserved for those times when I reminded him of himself when he was my age. “I felt the same way at your age, but, trust me, one day you’ll be glad you did.”

“But it’s all just stupid stuff, Dad.”

“Ah, but you’re learning how to learn, and that is the point,” he said. “Now, do you suppose you can get me another flagstone before this mortar dries out?”

The conversation was over. I hadn’t expected to win, but I could still make him feel bad about it. I heaved a sigh and grunted when I lifted the next rock.

He placed the stone and stared at it for a moment. It must have said something I couldn’t hear because my dad nodded at it, flipped it over, set it down, and announced, “Perfect.”

“Can I get a dog for my birthday?”

“Your birthday isn’t for another six months, Abra.”

“I know, but you said I could have a dog when I got older,” I reminded him. “I’ll be thirteen, that’s old.”

“Almost ancient.” He chuckled as he dipped the metal spatula into the bucket of concrete batter. “If you could have a dog, what kind of dog would you want?”

“A wolf,” I said.

“Abra Rachael Forrester!” I hadn’t heard my mother come in the room. “Stop it with that dog business, and you,” she pointed at my dad, “stop encouraging her.”

“But mom — ”

“I said no.” She spoke to the imaginary audience that always hovered somewhere over her head, “I swear she has an unnatural obsession with animals.”

“You’re the one who gave me initials that spell A.R.F.” I liked to rub that in whenever I could.

“Don’t sass me, young lady.” She swiped a manicured hand over her white Capri pants. “Honey, why won’t you just hire someone to do this fireplace, you’re making a mess.”

“Pride of workmanship,” my dad said without looking up.

“You and your little projects. If the maid quits, you’ll find the next one.” She checked the time on her diamond studded watch. “The Anasazi Gallery is showcasing a new artist out of Santa Fe, I’ll be back in an hour or two, Abra, you be cleaned up and ready to go when I get back.”

“Yes, mother,” I said to the floor.

Her Jaguar spit gravel as it climbed up the steep driveway. My dad and I didn’t speak until the roar of the throaty engine faded in the distance.

“You know, Abra,” he said, “you’ve been a big help this morning, but I can take it from here if you want to say goodbye to your friends before you go.”

“Yeah, okay.” I shuffled toward the back door.

I’d been studying the verbal dialects and body language of the animals in this canyon for a long time. I’d seen clear evidence of missing and mourning, but as far as I could tell, they had no word for goodbye. It seemed a human concept, and a sad one at that.

“Hey, Abra,” my dad called.

I turned to face him.

“I love you, kitten.”

My heart lightened and I grinned back at him. “Love you too, Daddy.”

I hopped off the back deck and trotted down the hill toward the creek, whistling my perfected Sparrow’s Midday Song. I didn’t want to spoil my last precious moments here with the sadness of goodbye, and I didn’t dare start following animal prints because I always lost track of time when I did that. Instead, I would savor this peaceful place for as long as I could. It would have to tide me over for a while.

At the water’s edge, I took off my shoes. After the jolt from the initial cold plunge, my body temperature adjusted, and I floated in the silky creek water. It felt so much better than the chlorinated water in the pool at our house down in Scottsdale.

A parade of clouds danced over the towering cliff wall that grew out of the far bank of the creek. The clouds’ shape shifted, revealing their inner spirit before disappearing over the other side of the canyon. A prancing poodle, then a unicorn rearing up on hind legs; the next set broke apart into a V, like geese flying in formation.

I couldn’t wait to be an adult, to be able to do what I wanted to do, when I wanted to do it. First of all, I’d sell our house in Scottsdale and live up here in Sedona at the cabin. Today, I’d ride my bike up to Midgley Bridge, and resume my search for the character old timers call “Big Ole Bear.” I’d get my sketchbook and be back here an hour before sunset to watch Mama Cottontail and her most recent litter of bunnies. She’d been so easy with my presence yesterday I didn’t want to break our routine. I’d eat pizza for dinner. I’d get a dog. I’d have three dogs. And a horse.

I floated a little longer before leaving the water to bake dry on the sand. The sun’s rays beat down on my skin, and made red geometric patterns behind my eyelids. A woodpecker drummed a hypnotic tune in a nearby tree. The music faded when my ears plugged up.

I tilted my head to drain out any creek water. It didn’t help. I swallowed hard several times as my parents had taught me to do on long airplane trips, but the pressure kept building until my heartbeat became the only sound in the world.

Then came the sound of a second heartbeat, slower than mine, but encased within my body.

My eyes snapped open.

She stood on the narrow ribbon of sand against the cliff wall. Diamonds flashed off the water that flowed between us. She wore suede moccasin boots with chunks of turquoise sewn around the top. Above her temple, thick ropes of matte black hair were offset by a silver-dollar sized shock of white strands. A chiseled black stone lay at the base of her graceful throat, and an assortment of feathers dangled from the handle of her walking stick. Her face shimmered like a mirage, first young and smooth, then old and weathered. Her serene black eyes didn’t waiver.

There were only two ways to get to the spot on which she stood: rappel down the cliff or wade through the water.

There was no rope hanging behind her. Her clothes were dry.

Was it her heartbeat I heard?

The corners of her mouth turned up.

Too much sun, dehydration maybe, this couldn’t be happening. I squished my eyes shut and pressed them against my knees, but her heartbeat remained strong and mesmerizing.

Another beat joined the rhythm, this one faster, but not discordant. The combination like the Hopi drumming ceremony my dad had taken me to last summer.

I dared myself to open my eyes.

An enormous gray wolf stood beside her. His head was as high as her waist, his celestial blue eyes intent, but not threatening. A breeze rippled his fur.

Then it happened. The woman lifted her arms out from her sides as if she were conducting a symphony. As her arms rose higher, a cacophony of pulsating life joined ours; beetles under the loamy soil, birds in the trees, even the trees themselves had a heartbeat.

I was hearing the surging life forces with my body more than my ears, but still it was deafening — and painful; as if my insides were rearranging themselves, struggling to make room to hold all this life.

Just as the scream was leaving my lips, something shifted inside me, and I let go. With that last shred of resistance gone, I exploded into a ball of golden light. Then there was only blackness.

When I came to, the woman and the wolf were gone.

Her walking stick lay on the ground beside me. The feathers fluttered in the breeze.

Twenty-One Years Later

Friday, March 20

Day One