Читать книгу The Amish Mother - Rebecca Kertz - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter One

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

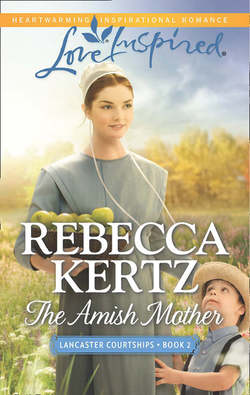

The apple trees were thick with bright, red juicy fruit waiting to be picked. Elizabeth King Fisher stepped out of the house into the sunshine and headed toward the twin apple trees in the backyard.

“You sit here,” she instructed her three youngest children, who’d accompanied her. She spread a blanket on the grass for them. “I’ll pick and give them to you to put in the basket. Ja?”

“Ja, Mam,” little Anne said as she sat down first and gestured for her brothers to join her.

Lizzie smiled. “You boys help your sister?” Jonas and Ezekiel nodded vigorously. “Goot boys!” she praised, and they beamed at her.

“What do you think we should make with these?” she said as she handed three apples to Jonas. “An apple pie? Apple crisp?”

“Candy apples!” Ezekiel exclaimed. He was three years old and the baby of the family, and he had learned recently about candy apples, having tasted one when they’d gone into town earlier this week.

Lizzie grinned as she bent to ruffle his hair. Ezekiel had taken off his small black-banded straw hat and set it on the blanket next to him. “Candy apples,” she said. “I can make those.”

The older children were nowhere in sight. Elizabeth’s husband, Abraham, had fallen from the barn loft to his death just over two months ago, and the family was still grieving. Lizzie had tears in her eyes as she reached up to pull a branch closer to pick the fruit. If only I hadn’t urged him to get the kittens down from the loft...

Tomorrow would have been their second wedding anniversary. She had married Abraham shortly after the children’s mother had passed, encouraged strongly by her mother to do so. She’d been seventeen years old at the time, but she’d been crippled her entire life.

“Abraham Fisher is a goot man, Lizzie,” she remembered her mother saying. “He needs a mother for his children and someone to care for his home. You should take his offer of marriage, for in your condition you may not get another one.”

My condition, Lizzie thought. She suffered from developmental hip dysplasia, and she walked with a noticeable limp that worsened after standing for long periods of time. But she was a hard worker and could carry the weight of her chores as well as the rest of the women in her Amish community.

Limping Lizzie, the children had called her when she was a child. There had been other names, including Duckie because of her duck-like gait, which was caused by a hip socket too shallow to keep in the femoral head, the ball at the top of her long leg bone. Most of the children didn’t mean to be cruel, but the names hurt just the same.

Lizzie had spent her young life proving that it didn’t matter that one leg was longer than the other; yet her mother had implied otherwise when she’d urged Lizzie to marry Abraham, a grieving widower with children.

Abraham had still been grieving for his first wife when he’d married her, but she’d accepted his grief along with the rest of the family’s. His children missed their mother. The oldest two girls, Mary Ruth and Hannah, resented Lizzie. The younger children had welcomed her, as they needed someone to hug and love them and be their mother. And they were too young to understand.

Mary Ruth, Abraham’s eldest, had been eleven at the time of her mother’s death, her sister Hannah almost ten. Both girls were angry with their mother for dying and angrier still at Lizzie for filling the void.

Lizzie picked several more apples, handing the children a number of them so that they would feel important as they placed them carefully in the basket.

“Can we eat one?” Anne asked.

“With your midday meal,” Lizzie said. She glanced up at the sky and noted the position of the sun, which was directly overhead. “Are you hungry?” All three youngsters nodded vigorously. She reached to pick up the basket, which was full and heavy. She didn’t let on that her leg ached as she straightened with the basket in hand. “Let’s get you something to eat, then.”

The children followed her into the large white farmhouse. When she entered through the back doorway, she saw the kitchen sink was filled with dirty dishes. She sighed as she set the basket on one end of the counter near the stove.

“Mary Ruth!” she called. “Hannah!” When there was no response, she called for them again. Matthew, who was eight, entered the kitchen from the front section of the house. “Have you seen your older sisters?” Lizzie asked him.

He shrugged. “Upstairs. Not sure what they’re doing.”

“Matt, are you hungry?” When the boy nodded, Lizzie said, “If you’ll go up and tell your sisters to come down, I’ll make you all something to eat.”

Jonas grabbed his older brother’s arm as Matt started to leave. “Mam’s going to make candy apples,” he said.

Matthew opened his mouth as if to say something, but then he glanced toward the basket of apples instead and smiled. “Sounds goot. I like candy apples.” Little Jonas grinned at him.

Matt left and then returned moments later, followed by his older sisters, Mary Ruth, Hannah and Rebecca, who had been upstairs in their room.

“You didn’t do the dishes,” Lizzie said to Mary Ruth.

The girl regarded her with a sullen expression. “I didn’t know it was my turn.”

“I’ll do them,” Rebecca said.

“That’s a nice offer, Rebecca,” Lizzie told her, “but ’tis Mary Ruth’s turn, so I think she should do it.” She smiled at the younger girl. “But you can help me make the candy apples later this afternoon after I hang the laundry.” She met Hannah’s gaze. “Did you strip the beds?”

Hannah nodded. “I put the linens near the washing machine.”

Lizzie smiled. “Danki, Hannah.” She heard Mary Ruth grumble beneath her breath. “Did you say something you’d like to share?” she asked softly.

“Nay,” Mary Ruth replied.

“I thought not.” She went to the refrigerator. “What would you like to eat?” Their main meal was usually at midday, but their schedule had differed occasionally since Abraham’s death because of the increase in her workload. Still, she had tried to keep life the same as much as possible.

“I can make them a meal,” Mary Ruth challenged. Lizzie turned, saw her defiant expression and then nodded. The girl was hurting. If Mary Ruth wanted to cook for her siblings, then why not let her? She had taught her to be careful when using the stove.

“That would be nice, Mary Ruth,” she said. “I’ll hang the clothes while you feed your brooders and sisters.” And she headed toward the back room where their gas-powered washing machine was kept, sensing that the young girl was startled. Lizzie retrieved a basket of wet garments and headed toward the clothesline outside.

The basket was only moderately heavy as she carried it to a spot directly below the rope. She felt comfortable leaving the children in the kitchen, for she could see inside through the screen door.

A soft autumn breeze stirred the air and felt good against her face. Lizzie bent, chose a wet shirt and pinned it on the line. She worked quickly and efficiently, her actions on the task but her gaze continually checking inside to see the children seated at the kitchen table.

“Elizabeth Fisher?” a man’s voice said, startling her.

Lizzie gasped and spun around. She hadn’t heard his approach from behind her. She’d known before turning that he was Amish as he had spoken in Deitsch, the language spoken within her community. Her eyes widened as she stared at him. The man wore a black-banded, wide-brimmed straw hat, a blue shirt and black pants held up by black suspenders. He looked like her deceased husband, Abraham, only younger and more handsome.

“You’re Zachariah,” she said breathlessly. Her heart picked up its beat as she watched him frown. “I’m Lizzie Fisher.”

* * *

Zachariah stared at the woman before him in stunned silence. She was his late brother’s widow? He’d been shocked to receive news of Abraham’s death, even more startled to learn the news from Elizabeth Fisher, who had identified herself in her letter as his late brother’s wife.

It had been years since he’d last visited Honeysuckle. He hadn’t known that Ruth had passed or that Abe had remarried. Why didn’t Abraham write and let us know?

“What happened to Ruth?” he demanded.

The woman’s lovely bright green eyes widened. “Your brooder didn’t write and tell you?” she said quietly. “Ruth passed away—over two years ago. A year after Ezekiel was born, she came down with the flu and...” She blinked. “She didn’t make it. Your brooder asked me to marry him shortly afterward.”

Zack narrowed his gaze as he examined her carefully. Dark auburn hair in slight disarray under her white head covering...eyes the color of the lawn after a summer rainstorm...pink lips that trembled as she gazed up at him. “You can’t be more than seventeen,” he accused.

The young woman lifted her chin. “Nineteen,” she stated stiffly. “I’ve been married to your brooder for two years.” She paused, looked away as if to hide tears. “It would have been two years tomorrow had he lived.”

Two years! Zack thought. The last time he’d received a letter from Abraham was when Abe had written the news of Ezekiel’s birth. His brother had never written again.

The contents of Lizzie’s letter when it had finally caught up to the family had shocked and upset them. Zack had made the immediate decision to come home to Honeysuckle to gauge the situation with the children and the property—and this new wife the family knew nothing about. His mother and sisters had agreed that he should go. With both Ruth and Abraham deceased, Zack thought that the time had come to reclaim what was rightfully his—the family farm.

He stood silently, watching as she pulled a garment from the wicker basket at her feet and tossed it over the line. He had trouble picturing Abraham married to this girl, although he could see why Abraham might have been attracted to her. But why would Lizzie choose to marry Abraham? He saw the difficulty her trembling fingers had securing the garment onto the clothesline properly. He fought back unwanted sympathy for her and won.

“You’re living here with the children,” he said. “Alone?”

“This is our home.” Lizzie faced him, a petite girl whose auburn hair suddenly appeared as if streaked with various shades of reds under the autumn sun. Her vivid green eyes and young innocent face made her seem vulnerable, but she must be a strong woman if she could manage all seven of his nieces and nephews—and stand defiantly before him as she was now without backing down. He felt a glimmer of admiration for her that quickly vanished with his next thought.

This woman and his brother were married almost two years. Did Lizzie and Abraham have a child together? He scowled as he glanced about the yard, then toward the house. He didn’t see or hear a baby, but then, the child could be napping inside. How did one ask a woman if she’d given birth without sounding offensive or rude? My brooder should have told me about her. Then I would know.

“I’m nearly done,” she said, averting her attention back to her laundry while he continued to watch her. She hung up the last item, a pillowcase. “Koom. We’re about to have our midday meal. Join us. You must have come a long way.” She bit her lip as she briefly met his gaze. “Where did you come from? I wasn’t sure where to send the letter. I didn’t know if you were still in Walnut Creek or Millersburg or if you’d moved again. I sent it to Millersburg because it was the last address I found among your brooder’s things.”

“We moved back to Walnut Creek two years ago—” He stopped. He wasn’t about to tell her about his mother’s illness or that he and his sister Esther had moved with Mam from Walnut Creek to Millersburg to be closer to the doctors treating their mother’s cancer. Mam was fine now, thank the Lord, and she would continue to do well as long as she took care of herself. Once his mother’s health had improved, they had picked up and moved back to Walnut Creek, where his two older sisters lived with their husbands and their families.

Zack had no idea how Lizzie’s letter had reached him. Their forwarding address had expired over a year ago, but someone who’d known them in Millersburg must have sent it on. He still couldn’t believe that Abraham was dead. His older brother had been only thirty-five years old. “What happened to my brooder?” She never mentioned in her letter how he’d died.

Lizzie went pale. “He fell,” she said in a choked voice, “from the barn loft.” He saw her hands clutch rhythmically at the hem of her apron. “He broke his neck and died instantly.”

Zack felt shaken by the mental image. He could see that she was sincerely distraught. “I’m sorry. I know it’s hard.” He, too, felt the loss. It hurt to realize that he’d never see Abraham again. He thought of all the times when he was a child that he’d trailed after his older brother.

His death must have been quick and painless, he thought, trying to find some small measure of comfort. He studied the young woman who looked too young to be married or to raise Abe’s children.

“He was a goot man.” She didn’t look at him when she bent to pick up her basket then straightened. “Are you coming in?” she asked as she finally met his gaze.

He nodded and then followed her as she started toward the house. He was surprised to see her uneven gait as she walked ahead of him, as if she’d injured her leg and limped because of the pain. “Lizzie, are ya hurt?” he asked compassionately.

She halted, then faced him with her chin tilted high, her eyes less than warm. “I’m not hurt,” she said crisply. “I’m a cripple.” And with that, she turned away and continued toward the house, leaving him to follow her.

Zack studied her back with mixed feelings as he lagged behind. Concern. Worry. Uneasiness. He frowned as he watched her shift the laundry basket to one arm and struggle to open the door with the other. He stopped himself from helping, sensing that she wouldn’t be pleased. He frowned at her back. Could a crippled, young nineteen-year-old woman raise a passel of kinner alone?

* * *

Lizzie was aware of her husband’s brother behind her as she entered the house with the laundry basket. She flashed a glance toward the kitchen sink and was pleased to note that Mary Ruth had washed the dishes and left them to drain on a rack over a tea towel.

“Mary Ruth, would you set another plate?” she said. “We have a visitor.” She was relieved to note that her daughter had set a place for her.

Mary Ruth frowned but rose to obey. Lizzie stepped aside and the child caught sight of the man behind her. She paled as she stared at him, most probably noting the uncanny resemblance of Zachariah to her dead father.

“Dat?” she whispered. The girl shook her head, then drew a sharp breath. “Onkel Zachariah.”

Watching the exchange, Lizzie saw him smile. “Mary Ruth, you’ve grown over a foot since I last saw you,” he said.

Mary Ruth blinked back tears and looked as if she wanted to approach him but dared not. The Amish normally weren’t affectionate in public, but they were at home, and Lizzie knew that the child hadn’t seen her uncle in a long time.

To his credit, Zachariah extended his arms, and Mary Ruth ran into his embrace. Eyes closed, the man hugged his niece tightly, and Lizzie felt the emotion flowing from him in huge waves.

“Zachariah is your dat’s brother,” she explained to the younger children.

Chairs scraped over the wooden floor as they rose from their seats and eyed him curiously. Zachariah had released Mary Ruth and studied her with a smile. “You look like your mudder.”

“Why didn’t you come sooner?” Mary Ruth asked. She appeared pleased by the comparison to her mother.

“I didn’t get Lizzie’s letter until yesterday,” he admitted. “After reading it, I quickly made arrangements to come.”

Mary Ruth nodded as if she understood. “Sit down,” she told the children in a grown-up voice. “Onkel is going to eat with us. You’ll have time to talk with him at the dinner table.”

The kitchen was filled with the delicious scent of pot roast with potatoes, onions and carrots. Mary Ruth had heated the leftovers from the previous day in the oven, and she’d warmed the blueberry muffins that Lizzie had baked earlier this morning.

Her eldest daughter set a plate before Zachariah and then asked what he wanted to drink. Standing there, Lizzie saw a different child than the one she’d known since Lizzie had married Abe and moved into the household. It was a glimpse of how life could be, and Lizzie took hope from it.

After stowing the empty laundry basket in the back room, Lizzie joined everyone at the table. The platter of pot roast was passed to Zachariah, who took a helping before he extended it toward Lizzie. Thanking him with a nod, she took some meat and vegetables from the plate before asking the children if they wanted more.

Conversation flowed easily between the children and their uncle, and Lizzie listened quietly as she forked up a piece of beef and brought it to her mouth.

“Are ya truly my vadder’s brooder?” Rebecca asked.

“Look at him, Rebecca,” Hannah said. “Don’t ya see the family resemblance?”

Lizzie looked over in time to see Rebecca blush. She addressed her husband’s brother. “You haven’t visited Honeysuckle in a long time.”

Zachariah focused his dark eyes on her and she felt a jolt. “Ja. Not in years. My mudder moved my sisters and me to Ohio after Dat died. I was eleven.” He grabbed a warm muffin and broke it easily in half. “I came back for a visit once when Hannah was a toddler.” He smiled at Hannah as he spread butter on each muffin half. “It’s hard to believe how much you’ve grown. I remember you as this big.” He held his hand out to show her how tall.

Hannah smiled. “You knew my mam.”

He had taken a bite of muffin and he nodded as he chewed and swallowed it.

“How come we haven’t met you before?” Matthew asked with the spunk of a young boy. “You didn’t come for Mam’s funeral.”

“I didn’t know about your mudder’s passing,” Zachariah said softly. “I still wouldn’t have known if not for Lizzie. I wanted to come to see you and your family before now, but I couldn’t get away.” He glanced around the table. “Seven children,” he said with wonder. “I’m happy to see that your mudder and vadder were blessed with all of you.” He smiled and gazed at each child in turn. “How old are you?” he asked Ezekiel.

Ezekiel held up three fingers. “Such a big boy. You are the youngest?” He seemed to wait with bated breath for Zeke’s reply, and he smiled when his answer was the boy’s vigorous nod. He then guessed Anne’s and then Jonas’s ages and was off by just one year for Jonas, who was four.

“How long are you going to stay, Onkel Zachariah?” Rebecca asked.

“Zack,” he invited. He leaned forward and whispered, “Zachariah is too much of a mouthful with Onkel, ja?” Then he shot Lizzie a quick glance before answering his niece’s question. “I thought I’d stay for a while.” He took a second muffin. “The dawdi haus—is it empty?” he asked.

“Ja,” Mary Ruth said while Lizzie felt stunned as she anticipated where the conversation was headed. “’Tis always empty except when we have guests, which we haven’t had in a long time...”

“Goot,” he said. “Then you won’t mind if I move in—”

Lizzie gasped audibly. “But that wouldn’t be proper...” The thought of having him on the farm was disturbing.

She became unsettled when Zack put her in the center focus of his dark gaze. “I’ll send for my mudder—and my sister Esther,” he said easily. “The three of us can stay there comfortably.”

Dread washed over Lizzie. “But—”

“Not to worry, Lizzie Fisher.” He flashed her a friendly smile as he buttered the muffin. “I’ll head home and then accompany them back to Honeysuckle. I won’t be moving in without a chaperone.”

But that wasn’t all that concerned Lizzie. She couldn’t help but wonder how long he—they—would be staying. Why did he want to stay? She’d never met her mother-in-law or any of Abraham’s siblings. What if they didn’t like her? What if they judged her incapable of managing the farm and decided that she was no longer needed? Could she bear to be parted from her children? Because, in her heart, they were her children although she hadn’t given birth to them.

She had enjoyed a good life with Abraham. She’d worked hard to make the farmhouse a home for a grieving man and his children. And Abraham appreciated my efforts, she thought. Right before his death, she’d felt as if he’d begun to truly care for her.

“You don’t have to worry about us,” Lizzie said quietly as she watched him enjoy his food. “We are doing fine.” Her hands began to shake, and she placed them on her lap under the table so that he wouldn’t see. “There is no need to return. I know your life is in Ohio now.”

Zack waved her concerns aside. “You’ll be needing help at harvest time. It can’t be easy managing the farm and caring for Abraham’s children alone.”

Lizzie felt her stomach twist. Zack, like everyone else, thought her incapable of making it on her own, and he’d referred to the children as Abraham’s. She experienced a jolt of anger. Abraham’s children were her children, had been for two years now.

Then a new thought struck her with terror. Zack was the youngest Fisher son. Wouldn’t that make him the rightful heir to his family farm? If so, had he come to stake his claim?

Lizzie settled her hand against her belly as the burning there intensified and she felt nauseous. Was she going to lose her home and her family—the children she loved as her own?

She closed her eyes and silently prayed. Please, dear Lord, help me prove to Zack that I am worthy of being the children’s mudder. When she opened them again, she felt the impact of Zack’s regard. She was afraid what having him on the farm would do to her life, her peace of mind and her family.