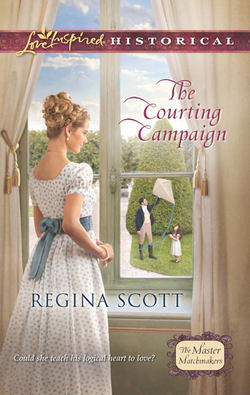

Читать книгу The Courting Campaign - Regina Scott - Страница 12

ОглавлениеChapter Four

Emma took her time settling Alice to sleep that night. The little girl was still wound up after dinner, telling Lady Chamomile all about the food, table settings and conversation. She seemed genuinely delighted with the whole affair. Why, then, had she claimed that Lady Chamomile was so unhappy?

Emma put the question to the girl as she tucked her into the child-sized poster bed in her bedchamber off the main room of the nursery suite.

Alice snuggled deeper under the goose-down comforter. “She is unhappy because she is an orphan.”

The answer cut into Emma. “Not all orphans are unhappy. Some know the Lord has better plans for them.”

Alice sighed, closing her eyes. “That’s good. But I think Lady Chamomile would be happier if we could find her a papa.”

Emma stroked Alice’s silky hair back from her face. “I’ll do all I can, Alice. I promise.”

She started the very next day at Sunday services. Dovecote Dale was served by a fine stone church in the center of the valley. Though the Duke of Bellington had responsibility for it, all four of the wealthy families—the Rotherfords at the Grange, Lord Hascot at Hollyoak Farm, the Earl of Danning at Fern Lodge, and the Duke of Bellington—had endowed gifts so that the little country chapel lacked for nothing. The building and bell tower had a fresh coat of white paint below a gilded steeple. The stained-glass windows glittered in the summer sun.

Inside, carved oak seats marched along the center aisle, and banners in rich silk draped the walls leading up to the alabaster cross. With his flyaway hair and silver-rimmed spectacles, the Reverend Mr. Battersea always seemed in awe of the place, honored to be given charge of their souls.

With the servants from the four estates, Emma listened with her usual interest to the readings and the sermon. But she was careful to be the first one on her feet and the last one to sit when the service called for the congregation to change positions. She wanted to take advantage of every opportunity to observe Sir Nicholas near the front.

From his absorption in his work to the way the staff seemed to revere him, she’d assumed he was a man like her foster father, though certainly not with Samuel Fredericks’s ability to denigrate those he saw as lesser beings. She was fairly sure her foster father was in a class by himself in that area. Mr. Fredericks attended church in his finest clothes, arriving in his best carriage. He worshipped with head high and shoulders broad, as if he wanted everyone around him to notice or he saw himself as a peer of the Lord instead of a humble penitent.

Sir Nicholas was different. Oh, his clothes were of fine wool and soft linen, but they were a bit on the rumpled side, and his cravat was more simply tied than that of Mr. Hennessy, the butler from the Earl of Danning’s lodge. Though she never saw Sir Nicholas pick up the Book of Common Prayer to follow the service, his lips seemed to be moving in the appropriate responses. Yet she detected little change in him, as if he were merely doing what he’d done a dozen times before.

Lord, what am I to make of this man? Last night I thought I saw a glimmer of a good father. But if he cannot give his heart to You, how can he give it to his daughter?

She received the beginning of an answer that afternoon, at the weekly Conclave.

Once a month, each member of the household received a Sunday afternoon off. She and Mrs. Jennings had the same day, and the cook had quickly introduced Emma to the place the servants gathered at the Dovecote Inn, not far from the church. The inn was a rough-stone building with flower boxes under the windows. More boxes under the overhanging eaves made homes for the doves for which the area was famous. On the upper floor lay a large private dining room, and it was there every Sunday afternoon that some collection of the local servants met to celebrate or commiserate their lots.

Some of the other houses, Emma knew, were more generous, so a few of the Conclave attendees like Mr. Hennessy were there nearly every Sunday. Others, like her, came once a month. Someone usually brought the largess of a master’s table—today it was fresh apricots from Lord Hascot’s orchard. And there was always tea and talk around the polished wood table.

The last time Emma had attended she’d brought her knitting and sat quietly on one of the tall upholstered chairs by the window, listening to the talk around her and the coos of the doves outside. She’d noticed that the unmarried servants tended to flirt with each other. She paid them no mind, as they didn’t seem to be serious.

Today, she had another purpose anyway, so she chose a seat near the stone hearth and confessed her goal to Mrs. Jennings.

“God bless you, Miss Pyrmont,” the cook said, face brightening. “You can count on my help—anything you want.”

“I’m trying to think of an activity Sir Nicholas could do with Alice,” Emma explained, edging forward on her seat as the other servants milled around them. “Something that might encourage him to forget his work for a time. You’ve known him for years, haven’t you? What did he like to do as a child?”

“Read,” Mrs. Jennings answered promptly, brushing back her skirts from the glowing fire. “Everything and anything. He knew the Latin names for things by the time he was Miss Alice’s age, and he knew most of the Gospels by heart by the time he was eight. He liked Luke the best. Said it had more facts.”

Of course. She’d suspected he set a great store by facts. And perhaps that was why he’d felt no need to use the Book of Common Prayer. He might well have memorized that, too! She studied the apricot she’d plucked from the bowl. “Did he have any favorite toys? Good friends?”

“Any so-called friends he found at Eton and lost in London,” the cook replied tartly. “But I’ll not gossip.”

“I will,” Dorcus said, ambling closer. The maid also had the afternoon off, but Emma had noticed she’d spent her time batting her eyes at a strapping footman from the duke’s household. “You should know what’s what, Miss Pyrmont,” she said now, pulling up a chair to sit beside Emma and the cook, “especially if you mean to become mistress of the Grange.”

“I have no such intentions,” Emma informed her, biting into her apricot to forestall additional comment. As if she’d ever consider marrying a man like Sir Nicholas! Her ideal husband would value his family, put their needs first.

“The more fool you, then,” Dorcus replied. “Being called a cheat never colored a fellow’s money.”

“That’s quite enough from you,” Mrs. Jennings declared. “Sir Nicholas is no cheat. If he says he made the right calculations, then he did.”

Dorcus rolled her eyes, but she rose and returned to her pursuit of the footman.

The cook leaned closer to Emma and lowered her voice. The warm scent of vanilla washed over Emma. “Never you mind her. All you need to know is that some of those philosophers questioned Sir Nicholas’s work. He left London because of it and gave himself completely over to his studies. All the more reason for you to carry on with your plan. And as for toys, he was quite partial to kites. Seems he’d read about some experiment by an American gentleman and was keen to repeat it.”

Kites, eh? Oh, for a windy day! But lacking that, surely there was something she could use from Mrs. Jennings’s stories.

Emma’s mind began to conjure up any number of activities designed to woo Sir Nicholas away from his work. She would have loved to speak further with the cook, but she could see Dorcus casting them looks. Best not to fan that flame. Emma thanked Mrs. Jennings and made polite conversation with the other servants until it was time to return to the Grange.

So, Sir Nicholas had studied from an early age, she thought as she walked up the lane from the village, the sun warm on her dark wool gown. Again, she wasn’t surprised. Indeed, the only surprising thing about her discussion with Mrs. Jennings was the reason Sir Nicholas found himself rusticating in Dovecote Dale.

His scientific calculations had obviously incensed his fellow natural philosophers to the point that he no longer felt comfortable among them. He must have made a tremendous mistake indeed. In her experience, it took a great deal to convince learned men to castigate their colleagues. Certainly she’d wished someone in authority to berate her foster father for his inhumane practices. But it seemed experimenting on children did not rise to the level of offense among the Royal Society.

There, she was starting to sound bitter again. She could feel her emotions like acid on the back of her tongue. One of the reasons she’d wanted to escape London was to leave her past behind, before those emotions poisoned her outlook, her hopes and her future. She was not about to give in to them now.

Help me, Lord. I know You must have sent me here for a reason. Show me the good I can do. Help me be a blessing.

Her own blessing was waiting for her on her return. In fact, Emma heard laughter before she reached the nursery.

As she paused in the doorway, she saw that Ivy was chasing the little girl around the table, her blue skirts flapping. Alice giggled each time she managed to evade capture. Ivy stopped immediately on seeing Emma, tugging down her apron and adjusting her lace-edged cap.

“Begging your pardon, miss,” she said, with a quick curtsey to Emma, “but someone would refuse a tickle.” She glanced pointedly at Alice, who covered her mouth with both hands. The giggle still slipped out.

Emma ventured in. “Tickles before dinner? What am I to do with the pair of you?” She clucked her tongue with a smile.

Alice dropped her hands and hurried to the table, slippers skimming the rosy carpet. “Do you wish a tickle, too, Nanny?”

Now Ivy giggled before a look from Emma sent her hurrying out to help Mrs. Jennings finish the Sunday dinner.

“Not at the moment,” Emma assured her charge. “And I’m guessing the rest of the household is not up to laughter either on a quiet Sunday evening.”

Alice climbed up into her chair and waited for Emma to push her up to the table. “I didn’t mean to make so much noise,” she said, face scrunching. “I know I shouldn’t bother Auntie or Papa.”

All at once the ideas that had been germinating in Emma’s mind sprouted into bloom. Her smile grew.

“Not at all, Alice,” she said, pushing the girl up to the table and going to her own seat to wait for the dinner tray to arrive. “I believe your father needs something to wake him up. And I know just how we can go about it.”

* * *

The next morning, Nick scowled at the scrap of wool sitting on his worktable. Two days ago the stuff had burst into flame immediately; his laboratory still gave off the grit of charcoal from the smoke even though he’d spent Sunday afternoon airing the place and setting up his next experiment. Today, under a different chemical treatment, the material would not so much as smolder. That didn’t bode well for success.

It had sounded like a relatively simple problem to solve. Coal miners required light to do their jobs deep underground. Coal mines gave off firedamp, a noxious gas that appeared to be a form of the swamp gases Volta had studied. Combine a flame with a patch of the gas, and the resulting explosion could kill dozens. The Fatfield Mine in Durham had lost thirty-two men and boys just two years ago after their candles ignited firedamp.

Still, the solution eluded many. Dr. William Clanny had developed a method of using water to force the air into a lamp, protecting the flame from the gas. While ingenious, the device was impractical to carry into the mines. Sir Humphry Davy, the chemist, was approaching the matter from a heating perspective. An enginewright named George Stephenson thought burnt air was the key to separating the flame from the firedamp.

Nick had been working with a team of natural philosophers led by Samuel Fredericks to consider the properties of the materials that could compose a lamp. They had thought they’d come across a likely combination of candidates, but their first attempt to test the lamp had resulted in the deaths of three men and a boy a little older than Alice.

The muscles in his hand were tightening; he shook them out. Obviously this composition would not meet his needs. He required something that would burn in the presence of oxygen but not firedamp, not the other way around. He’d have to start over.

He rocked back on his stool, took a deep breath. He was certain the secret lay in the composition of the lamp’s wick. He’d already had a glassblower create the appropriate chimney to partially isolate the wick from the gas and the blacksmith create the brass housing for the fuel. He’d tried wool, cotton and linen and various combinations of fuel, to no avail. One attempt was too flammable. Another, like this, wasn’t flammable enough. There was no easy in between.

Which somehow reminded him of his life of late.

Outside, he heard a noise. More like a bump and shuffle, really. Very likely the gardener was attempting to replace the shrub Nick had withered when he’d dumped a batch of chemicals after he’d first moved to the Grange. He’d learned to be more cautious in his disposal habits. He didn’t want Alice to accidentally come in contact with the stuff.

Perhaps he ought to try silk next. Kressley had recently proposed its use in commercial lamps. But he wasn’t sure it was practical by itself. Perhaps coated with some chemical to moderate the flammability.

The noise outside was rising in volume now, and he thought he made out words. Was that someone singing? He could place neither the tune nor the key.

Nick shook his head to clear his mind. It didn’t matter what was happening outside. He had work to do. His family’s income came in large part from the leasings of the mine to the east of the Grange. He felt as if he owed it to those men personally to find a safer way for them to work.

He still remembered the first time his father had taken him to the mine, on a gloomy day when Nick was eight. Nick had been about to leave for Eton, and his father seemed to see Nick’s imminent departure as reason to spend time together. Certainly Nick could find no other logical hypothesis for why his father had suddenly remembered his existence.

They’d driven to the mine in the gig, his father at the reins, but obviously determined to show his knowledge of the place. He’d pointed out the shadowed entrances, the stiff metal outbuildings, the men and boys laboring under the weight and darkness. His father’s face had glowed with pride as he described the prosperity, the accomplishment.

Nick had been more interested in how the mine worked. He’d prevailed upon his father to allow him to be lowered in one of the baskets into the pit. He hadn’t been afraid, even as daylight disappeared and blackness swallowed him.

Open-flame lamps produced more light at the bottom, where scarred walls told of past discoveries. Sitting on the floor had been a boy of six, face grimy, clothes grimier. One small fist enclosed the handle of a wooden door built into the wall.

“What are you doing?” Nick asked as he stepped from the basket onto the uneven floor.

“Manning the wind-door,” the boy replied with pride. “We open and close the doors to keep the air flowing.” As if to prove it, he heaved on the handle, and air rushed past Nick, setting the basket beside him to swaying.

That grimy face was the one he saw when he thought about the need for his safety lamp.

Something hit the door of his laboratory, hard. The memory faded. Enough of that nonsense. Each day down in those mines, hundreds of men and boys risked their lives. While it was not entirely his fault a replacement had not been found, he could not forget that a mistake of his had cost lives as well as his status as a natural philosopher. He would not rest until...

“What on earth is all that noise?” he demanded, jumping off his stool. He strode to the door and jerked it open.

Alice gazed up at him, little fingers barely grasping a battledore. The wooden racket was nearly as long as she was. Her eyes seemed disproportionately large for her face, but one look at him and they brightened. “Papa!”

“Alice,” he returned, bemused.

“Good day, Sir Nicholas,” Miss Pyrmont called from a short distance away. She swung her battledore up onto the shoulder of her brown wool gown. He seemed to remember the game that required the rackets also involved a shuttlecock that was cork at one end and feathers at the other. Hardly sufficient to make noise. He struggled to develop a hypothesis about the source of the thuds against his door.

“Miss Pyrmont,” he greeted her. “Why are you here?”

She cocked her head as she strolled closer. She wore no bonnet. Perhaps they were not required for a nanny as they seemed to be for other ladies. Certainly Charlotte and Ann had never left the house without one. Either way, the sunlight blazed against her pale hair.

“We’re playing a game,” she explained with a smile as she approached him. “I would think that would be obvious to a gentleman given to observation.”

Alice was still gazing up at him as if equally surprised he hadn’t figured it out.

“I can see you are playing a game,” Nick replied. “What I don’t understand is why you must play it here.”

“Don’t you like games?” Alice asked.

That was not the issue, but he didn’t think her nanny cared. Indeed, the look in Miss Pyrmont’s muddy eyes as she stopped in front of him was nothing short of challenge.

“Games can be enjoyable,” he started, when Alice dropped her battledore and seized his nearest hand with both of hers.

“Oh, good!” she cried. “Come play!”

He took a stutter-step forward to keep from bowling her over. “No, Alice. Not now.”

He had meant the tone to be firm, but not sharp. His daughter obviously had a different interpretation. She stopped and dropped his hand, and her lower lip trembled. “I’m sorry. I thought you wanted to play with me.”

How was he to answer that? Alice could not understand what drove him. She was too little to remember her mother’s death much less the recent tragedies associated with his work. She couldn’t know the depth for which he needed to atone. Only God knew how much Nick had failed, another reason he found it hard to take his concerns to the Almighty.

Miss Pyrmont had reached their sides. She knelt, brown skirts puddling, and took Alice’s hands in hers. “I’m sure your papa would love to play with us, Alice. We simply caught him at a bad time.” She glanced up at him. “Isn’t that right, sir?”

Nick blew out a breath. “Yes, just so. Thank you, Miss Pyrmont.”

She gave him a quick smile before returning her gaze to Alice, whose face was still pinched.

“Your father has important work to do,” she explained. “We wouldn’t want to keep him from it.”

“Noooooo,” Alice said, the length of the vowel proclaiming her uncertainty.

“Thank you for understanding, Alice,” Nick said. “I’ll be done soon, and then I’ll have more time for games.”

Alice brightened again. How quickly she believed him and with no evidence. A shame his colleagues didn’t have such faith in him. A shame he’d lost such faith.

Miss Pyrmont rose, all smiles, as well. In fact, he noted a distinct change in her appearance when she smiled, as if she somehow grew lighter, taller. The change seemed to lighten his mood, as well. Curious.

“I’m so glad to hear you’re making such progress, Sir Nicholas,” she proclaimed. “Do you think you will be done today, then?”

He could not be so encouraging. In fact, her brightness suddenly felt demanding, asking things of him he knew he could not achieve. Nick took a step back. “Not today, no.”

“Tomorrow then?” she persisted, following him.

“I cannot be certain,” Nick hedged, glancing over his shoulder for the safety of his laboratory.

“The next day, then,” she said with an assurance he was far from feeling. “We should celebrate over tea.”

“You’ll like tea, Papa,” Alice said as if he would be experiencing the brew for the first time. “The bubbles make kisses.”

Kisses? Though he knew for a fact that tea and kisses did not equate, he found his gaze drawn to the pleasing pink of Miss Pyrmont’s lips. As if she’d noticed his look, she took a step back, too.

“What time should Alice and I be ready for you to join us?” she asked.

She seemed to assume his agreement this time. Assumptions were dangerous things, to be used only when no source of direct observation or calculation was available. He did not think it warranted in this instance. Surely Miss Pyrmont had observed that he was too busy for a social convention like tea.

“I fear I cannot give you a precise day when I will be finished,” he told her. “Now, if you’ll excuse me, I should get back to my work. I suggest you find somewhere else to play.”

Alice seemed to crumple in on herself, and he felt as if a weight had been placed on his shoulders. He wished once more he knew how to make her understand. Perhaps she would appreciate his work one day, when she was older. He could imagine having her sit beside him as he explained his process, his hypotheses. She could help him think through his logic, question things he’d perhaps taken for granted. It seemed he needed someone like that in his life, or he would never have overlooked the mistakes in his calculations, much less his wife’s illness.

But as he turned to go, he caught sight of Miss Pyrmont’s face. Her chin was thrust out, her eyes narrowed, as if she could not understand him. She was certainly mature enough to realize the importance of his work, might even have been of some use to him in furthering it. But if possible she looked even more disappointed than Alice.

With him.