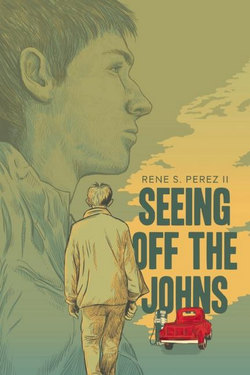

Читать книгу Seeing Off the Johns - Rene S Perez II - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеConcepcion ‘Chon’ Gonzales didn’t partake of Greenton’s joy in those forty seconds. Instead he forced himself into eighty seconds of fake sleep interrupted by the sounds of sirens and the loud hootings of his neighbors and parents. Even his little brother Pito went out to cheer them on. The traitor. Chon pretended to sleep through the Johns’ parade to prove some point—a point he couldn’t quite define—to his family and to all of Greenton, but the town failed to notice his silent protest.

The night before, Pito made a big deal of asking their mother to wake him up early so that he could join in the morning festivities.

“Promise me, Mama,” he had begged, unnecessarily.

Chon’s parents wanted Pito to witness what could result from hard work and skill, but they knew about Chon’s sulky dislike of John Mejia so they didn’t say much.

“Alright. Go to bed,” their mother said.

Pito clapped his hands excitedly and went to his room, avoiding his brother’s eyes. In the silence that followed, the rock chords of a beer commercial blaring from the TV underscored Chon’s anger at his brother and now at his parents. Chon sat at his end of the couch while his parents sat at the other, making a big deal of not mentioning the obvious—John Mejia’s spectacular success.

Chon spared them any further awkwardness by getting up, grumbling something about being tired after last night’s partying, and went to his room where he pretended to be asleep.

Chon hadn’t always cringed at the thought of the Johns, particularly at the thought of Mejia. His animosity was only four years old. It had existed for just under a quarter of his life and for the entirety of what he considered to be his manhood, from thirteen to that very day.

In elementary school, Chon had been the cutest and—that indicator of alpha male status—the tallest boy in his grade. Even then, it was clear to him that he could have for his girlfriend any girl he chose. Naturally, he chose the prettiest girl in school. From third grade through seventh, Chon Gonzales, the boy with the glowing hazelnut/amber brown eyes, had Araceli Monsevais at his side.

During this time, Chon played on Little League baseball and football teams alternately with and against the Johns. At many of these games, Araceli would sit in the stands and cheer Chon on. While she was there, more accurately, to cheer on her cousin Henry, who seemed always to be on any team Chon was on, Chon played every second in right field as though she were there for him and him only. He would make to run in the direction of any ball that was hit. In the event a ball was hit his way and he missed it, as he was likely to do, he would hustle to pick it up, try his damnedest to throw it where it needed to go, and pray that Araceli couldn’t see from the stands the tears that were burning in his eyes.

One of the lasting memories of Chon’s baseball days was the game when he had the good luck to smack a high curve—one the too-young pitcher he was facing shouldn’t have been throwing—with the sweet spot of his TPX, launching the ball into left-center field. After a sprint fueled by the desperation of a boy prematurely aware of the fleeting nature of Little League glory in a small town—a boy who knew that he wasn’t likely to ever hit a baseball that well again—and with the benefit of a throwing error from a left fielder who had fought with his center fielder teammate for the ball, Chon had enough time for a stand-up triple. He slid—Pete Rose-style—anyway. It was a great experience while it lasted. It should have made a great memory, except that when he got up and dusted himself off, he realized that Araceli hadn’t seen it. She had gone to get candy at the concession stand or to use the restroom or to do something that caused her to miss Chon’s only hit of the day—and the only extra-base hit of his short career.

That was the story of their relationship: poor timing and an inability to recreate a moment of glory.

That night, on the eve of the Johns’ departure from town, Chon lay awake thinking of possible ways in which he would win back the woman he felt destined to be his. Tomorrow Mejia would have the future and the rest of the world on the end of a string. With all of that good fortune coming to him, couldn’t he leave something behind?

John Mejia haunted Chon’s thoughts. But it was hard to extricate Greenton’s Romeo from its Juliet, if even only mentally—Chon couldn’t picture any version of Araceli without John Mejia at her side, at least any version he would want to focus on. The only John-less images he had of her were pre-John images.

The truth was, Chon could really remember hardly anything about his years with Araceli. How much attention did any boy pay to a girl before he is interested in sex? His interest in her was pure and fleeting, like so many other interests he picked up and put down when he was young. Sure they held hands, but only until their hands got sweaty. Sure they kissed, but what good is kissing when the kissers have no idea what it could lead to? They hadn’t even started talking on the phone in earnest teenage obsession.

And that’s all the Araceli that Chon could lay claim to: a pre-John one, an Araceli that Mejia seemed happy to concede to Chon, because he was never jealous. Mejia never registered Chon as a threat to his relationship with the most beautiful of Greenton’s daughters—not when he first took her from Chon, and not any time thereafter.

On the day he took her, a day at the beginning of seventh grade, Mejia made a big deal of waiting at Araceli’s locker to walk her to class. That was something Chon had done every now and then with Araceli, the girl he called his girlfriend, but who hadn’t called him her boyfriend in quite some time. While Araceli had achieved a firmness and amplitude of body in the summer between sixth and seventh grades, Chon, whose voice had not yet begun to break and squeak much less dip to the smooth baritone tenor of John Mejia’s, hadn’t seemed to notice. Once again, timing was off. Except that, this time, it was Araceli who hit for the fences and Chon who missed seeing it.

John Mejia didn’t miss it though. Chon never stood a chance against so much facial hair and muscles and bass and testosterone and so much burgeoning local celebrity. The Johns were already beginning their athletic takeover of the hearts and minds of Greenton. Strained as his relationship had become with Araceli, Chon wouldn’t have stood a chance against the opposition of any interested older boy. He didn’t fault Araceli for having snubbed him for one of Greenton’s two crowned princes. He simply figured, naively, that when his maturity and biology caught up to hers and to Mejia’s, he would win her back.

Time didn’t treat him so well though. He was plagued with such a case of acne that not even Christ would have touched him. He shot up in height from five nine to six four but couldn’t seem to gain an ounce of weight. Come eighth grade, he was a freak of nature and Araceli was dating the freshman starting quarterback and third baseman of Greenton’s most important varsity squads.

Chon lay in bed the morning of the Johns’ departure without a clue. How would he get Araceli back? His complexion was finally clearing. He’d managed to put on eight pounds during his junior year of high school. He no longer only saw ugly when he looked in the mirror. After some late night misadventures with Ana at work, he knew that he was walking around with hot blood in his veins and some experience to complement the desire that emanated from between his legs, controlling his every thought sometimes. But still Chon could only think of Araceli’s beauty in the context of her prom picture with Mejia.

So he slept uneasily, waking up from his light sleep when he heard Pito ask, “Did I miss it?” Their mother assured him that he hadn’t and shushed him up.

Chon could have just rested there quietly, staring at the ceiling or at the TV on mute or reading a magazine. Instead he forced his eyes shut and crammed his head between his pillows. Sleeping through the town’s final celebration of the Johns would harden Chon’s resolve to continue loathing a guy who never really did him wrong.

The first rush of applause, when the Robison family drove by his house en route to the Mejia’s, didn’t make Chon open his eyes. And he had fallen asleep for real by the time the sound of sirens and shouts passed by him some time later, waking him for the second it took him to realize what was going on. He closed his eyes in a calm and sinister fashion, like he imagined a super villain would. Because isn’t that what he was—Bizzaro trying to take Lois Lane from Superman?

When the day was over, he could tell himself he had slept through seeing off the Johns. He would emerge from his bomb shelter, guns in both hands, ready to fight the Nazis or the Russians or the Iraqis. He would right the wrong that had never really been done to him in the first place.

For good measure, and to put some distance between himself and his own stand—because what kind of stand would it have been if he’d backed down straightaway after not having made his point—Chon didn’t leave his room or get out of bed until three pm, thirty minutes before he had to go into work. He slammed the door to his room behind him and took the quickest of showers, brushed his teeth, slapped on some deodorant, combed his hair, then hopped in his car, an ’89 Dodge Dynasty that had been dubbed the Dodge-nasty by Chon’s best friend in town and, thus, the known world, Henry Monsevais. Henry was also Chon’s old Little League teammate and perennial bottom-of-the-order brother. And he was Araceli’s cousin, younger by two weeks. Henry had taken the liberty of severing the cursive connection between the y and the n and scraping off the first two letters of the logo on the trunk of Chon’s car. When Chon saw what Henry had done, he laughed and said, “It fits.”

When, for the remainder of his sophomore year, everyone in school had taken to calling Chon “Dodge-nasty,” he was less than pleased.

“I’m sorry, man. If I had known—” Henry apologized when John Robison said, “Later, Dodge-nasty” out the window of his Explorer as he cruised by. Chon cut Henry off.

“Don’t worry about it,” he said. He was at the pinnacle of teenage self-loathing. “It fits.”

Everything looked normal on the way to work. There weren’t any more or less cars on the road. The driver of every car loosened his grip on his steering wheel to pick up the index finger and pinky of his two o’clock hand in the form of a wave. There were more kids in the yards he drove by—playing football or hide and seek or whatever kids play—but today was the first Saturday of the summer, so that was to be expected.

When he pulled onto Main, he saw the “Hook ’em, Johns” banner bobbing up and down, lazing in its perch over town. It was almost enough to make Chon cringe except that the Longhorn symbols on either side of the banner reminded him that the Johns were moving away, on to bigger and better. They would meet new friends, new girls—women even—in Austin. Greenton, Texas and Araceli Monsevais and that microcosm of relevance—that blip that didn’t even register on Mejia’s radar—Chon ‘Dodge-nasty’ Gonzales were to be forgotten. They would be written off as a part of the quaint past.

“Good luck,” Chon said, flipping off the banner, “and good riddance.”

Chon parked the Dodge-nasty on the car-length path behind The Pachanga convenience store and gas station, worn bare to dirt by years of employee parking. Artie Alba, the store’s owner who lived in San Antonio but kept close watch on his store through reports he would receive from his in-town cousins, had purchased the Greenton Filling Station and renamed it. He knocked out a portion of the wall behind the register to install a drive-through window for the convenience of drunks too lazy to get out of their cars to buy beer.

Someone had spilled soda on the floor in front of the fountain area. Judging by the stickiness of the syrup that remained, the soda had been spilled three hours before. The beer cooler was near empty which didn’t make sense since beer sales were only permitted after noon, and the store’s solitary unisex bathroom was a mess, bombshat diarrhea all over the bowl. This is what Chon could look forward to for half of the summer’s work days, because now that he didn’t have school as an impediment or an excuse, he would be splitting the mid-shift with Ana, which meant coming in after Rocha, the septuagenarian drunk with his Olmec complexion and his malformed hook of a baby-sized left hand and his refusal to do any of the work that he was otherwise able to do when The Pachanga was still the Greenton Filling Station and Art Alba still lived in town.

“It’s my hand, bro,” he used to say, when asked about the state of the store at the end of the 7 to 3:30 shift he worked exclusively. “Mi manito nanito.”

Now all he would say if so confronted was, “Fuck you, kid. Do it yourself.”

And so Chon would have to do just that: face lakes of high fructose corn stickiness, mountains of unstocked beverages in the tundra of the walk-in, and the aftermaths of shit-bomb tsunamis.

He walked to the back and put the mop bucket in the sink to fill before he even clocked in. He met Rocha at the wall-mounted time card tower. “How was it today?”

Rocha grumbled from the bottom of his throat, not bothering his tongue to syllablize nonsense.

“Well, the store looks really great.”

“Chinga tu madre.”

“¡Ay papí! I love it when you talk dirty to me!”

“Pinché maricón desgraciado.”

His spirits lifted as they were, Chon mopped up the fountain area with a smile on his face. His day wouldn’t turn shitty until he hit the bathroom.

After a few hours of cleaning and relaying between the cooler, the drive-up window (at the sound of the doorbell buzzer on the bottom window sill), and the counter (at the sound of the bells above the door) like Pavlov’s dog, The Pachanga was clean, stocked, and operating as slowly as it did on any other day.

Chon had been sitting on the stool behind the register for as long as it took his mind to wander to thoughts of Araceli—which is to say it hadn’t been long—when he was distracted by the honking of a car passing by. It took him away from his favorite image of Araceli, remembered from the previous year’s luau-themed homecoming dance. She wore a bikini top—white with pastel polka dots of varied size, like stars approaching a spaceship Chon often fantasized he was piloting—with a simple flowerprint cloth tied at her waist and a pink lily in her hair. The Mejia goon in his blue board shorts, leather chanclas, and muscle-hugging designer tank top, though, was a part of that picture, a part Chon could only ever just blur out of focus, but never fully airbrush away.

He looked outside to see a line of cars making its way down Main to Viggie. It was a strange sight, so many cars on the road traveling in the same direction when there wasn’t a baseball or football game to get to. Was there a funeral in town? No, the cars were going in the opposite direction of both the church and cemetery. Besides, how could someone in town have died without Chon hearing about it? No matter how good he was at shutting his eyes and separating himself from what went on around him, he would have heard that kind of news the second it hit town.

It wasn’t just the cars. There were people on foot too, crying as they walked down the street. Chon felt like someone wading upstream in a rush of panicking hordes, unaware of the calamity and terror from which they were fleeing. His curiosity at the sight morphed to fear. That panic was interrupted by the bells over the storefront entrance. It was Henry, flushed and breathless.

“Holy shit, bro, they’re dead,” he blurted out. Henry’s face was covered with sweat, much of which had collected at the corner of his mouth on his pathetic Fu Manchu whiskers.

“Who’s dead?” Chon said.

“The Johns. There was an accident. They’re dead.”

Chon felt his eyebrow rise of its own volition.

“Give me the keys to the Dodge-nasty, man. Everyone’s going to the Robison place,” Henry said. He looked out impatiently at the cars and pedestrians making their way to the action. “Holy fuck,” he said to himself.

Chon took his keys from his pocket and slid them on the counter. Henry picked them up.

“Alright, man. You’re off at midnight, right?” He didn’t wait for an answer. “I’ll be back by then. Hay te watcho.”

Then he left. After a short time, everyone seemed to have left. The streets of Greenton were empty, Chon Gonzales alone on his stool to contemplate what it all meant.

Andres and Julie Mejia had eaten breakfast and then made love. They’d planned on being louder, but it was as silent and meditative as the first time after their oldest son Gregorio was born. Goyo was asleep in his crib, put down after his changing and bottle. Andres would swear that the look in his eye that day had nothing to do with the fact that it was the day the doctor-mandated moratorium on sex had ended.

“I really didn’t know,” he said whenever Julie brought it up afterwards. It became one of their favorite stories to share in intimate moments. “And who says I would have waited one second longer anyway, no matter what any doctor said.”

Andres had done some boxing in his teen years and some volunteer firefighting with the county. He had worked odd jobs stripping roofs and picking and hauling watermelons, at the same time serving as a mechanic’s apprentice. All of this work led to his still impeccable physique, a source of pride and shame to Julie. She had always been big. On the arm of her Mexican Adonis, her Adanis, she figured all anyone could see was the disparity between the two of them. She couldn’t see, like Andres did, like her sons did, like everyone did, that she wore every ounce of her weight perfectly—her face was exactly symmetrical save for a beauty mark above her lip on the right side, her hips and thighs would have broken the charcoal pencils of a thousand would-be artists trying to master curves, even her belly with its uniform softness which made Andres crazy when he wrapped his biceps and forearms around it—all of it transcended the oppression of Barbie, drove men who were into bigger women wild, and made men who weren’t see how they might be.

When Andres and Julie were done, sweaty bodies glowing in the strange glow of daylight filtering in through the shades, they lay in bed thinking that life would be like this from now on. After a day at work—him at the shop, her at the library—it would be making love—fucking, if that was the case—at any time, volume, or place in the house they so chose. They were both thinking, though they didn’t say so to each other, that they hadn’t felt like this since they’d played hooky back in school—lied to mom about a stomachache or to dad about menstrual cramps. But now they had no one to lie to. There was no shame in being in bed in the morning like this, only pride. Pride in their boys and pride in themselves for having made them.

Julie got out of bed to shower. Then Andres did. Then they made love again, remembering their resolution to not stifle the moans and grunts and climactic screams that had been building up in them for twenty-three years. After this they took to the shower together, during which she scrubbed his chest and back and he massaged shampoo gently on her scalp. They stood dressing at their respective ends of the bed where their bureaus were. Andres made a playful lunge at her, and she laughed.

“No,” she said. “We’ll be late.”

They took his truck, which he never took anywhere but to the shop or out on a call. He was not only Greenton’s most trustworthy mechanic, he was its one-man roadside assistance. Goyo helped. Every now and then, John did too, as the case demanded it.

They hadn’t even made it to the end of Sigrid when they were greeted by their neighbor Pedro Guerra who gave a shout to the couple and picked up his right hand, ring and middle fingers held down by his thumb.

“Hook ’em,” he shouted, and flashed a two-tooth smile.

Andres managed to wait until he pulled onto Viggie before he burst into laughter. Julie couldn’t hold it that long. Three other cars honked at the Mejias, extending the same greeting. They even saw other people salute friends and neighbors with their index fingers and pinkies. It seemed that the whole of Greenton was going to do this for the next four years, bathed in a sea of burnt orange until the boys graduated and went pro, as was their plan, and a new color was adopted. But pro ball teams didn’t have hand signs like the Longhorns did. Hook ’em just might turn into Greenton’s new hello.

Arn Robison had the fire going, coals nice and grey, grill warmed and ready for whatever flesh needed cooking. Andres and Julie walked straight to the Robison backyard to hug Arn and Angie. She was still as beautiful as she was when she met Arn. That made the couple a funny sight because Arn had lost most of his hair and gained quite a bit of weight in the interceding years.

The Mejias were always told not to bring anything but appetites to the Robison house. After so many dinners with them, they were finally comfortable in complying with the familiar directive. A fruit tray had been set out. When the Mejias arrived, Angie ran inside and returned with a tray holding four big New York strips.

“This is too much,” Julie said, as she often did at the Robison’s get-togethers.

“Who can begrudge us an indulgence on such a great day?” Arn looked up. But he was not talking about the weather, which was prefect by Greenton standards, the dry heat not so bad under the shade of a tree or, as in the Robison’s case, a deck covering. Andres looked at Julie and they smiled their secret at each other. No one could.

“And in that spirit,” Arn said, “a toast.”

He held out a glass of bourbon to Andres while Angie poured a couple of margaritas in stemware waiting on the table. They raised their glasses, the four of them, and looked at each other as though they’d all just rolled out of bed after an afternoon of intimacy.

“To our boys,” Angie said.

“To our Johns,” Julie added.

“To our Johns,” they all said.

They had always gotten on this well, despite their difference in age. The Robisons had their John late in life, after having been told they never would. Though the Mejias were in their early forties and the Robisons were well into their sixties, they were friends because their boys were friends, best friends. Well before Araceli sat down to dinner with the Mejias, they’d had John Robison over as a guest at countless dinners. They were not special dinners. The Mejias rarely strayed from their standard foods—fideo and meat, tacos and chalupas, easy ricotta-free lasagna, beef and, more rarely, chicken enchiladas. But they didn’t have to be special. They were not about anything more than two friends hanging together outside of school, the diamond and the huddle.

The Robisons, on their part, seemed to regard the Mejias—as some people do with their friends who are more than two decades their junior—as younger siblings and as children of their own. The Mejias had felt a sting of embarrassment when they went to the first of their dinners with the Robisons. They knew the Robisons were well off—Arn was the youngest grandchild and sole remaining Greentonite of Samuel and Wilhelmina Robison, who’d made a small fortune on a ranch outside of town. Arn had inherited money from them. He’d worked hard all his life as a horse doctor and hit big on some investments. But the Mejias weren’t prepared for the kind of food the Robisons were used to.

That first meal together, the Robisons served blackened catfish, which Julie thought was too fancy for her taste. Over a decade of dinners, though, the Mejias accepted that there would be the occasional lobster tail or swordfish or prime rib or hundred-dollar bottle of bourbon.

On that night—the night after the Johns headed to Austin—Arn grilled the steaks and served twice-baked potatoes he’d made earlier and left warming in the oven. The men switched to beers, the women to margaritas, with an occasional shot of the hard stuff in between. Angie brought out a stereo and CDs and looked for whatever stations could be caught from Corpus and Laredo playing the country and conjunto music that they all knew and loved, even Arn. The sun was flirting with the horizon, day with night, when the phone rang.

“They’re probably already there,” Angie said before she got up from the table. She didn’t want John’s first call home to go unanswered so she made to run to get it but slowed her pace when the tequila and bourbon hit her. She left Arn and the Mejias waiting at the table, their talk quieted in the hope that they could soon talk to their sons who were on the other end of the line.

Then they heard Angie scream.

On the stereo, George Strait sang that he would be in Amarillo by morning.

Chon’s first thought—right after Henry brought him the news, picked up the car keys and ran around the side of The Pachanga to get in the Dodge-nasty—was that the Johns death was an act of God, given to him as a personal blessing because he was a good Catholic boy who had completed all of his sacraments and said grace before every meal. He was too ashamed to ever share that thought with anyone though, not with Henry or his mother or even Araceli if she ever asked. He would never tell a soul.

The thought died quickly anyway, almost as soon as it had come to him. It was replaced with the image of an old couple crying over the loss of their only son; of the mechanic who had brought the Dodge-nasty back to life after Chon had bought it for $350 off the street and his wife who had checked out books to him—Dr. Seuss to Mark Twain—weeping at the passing of their youngest. And of Araceli Monsevais, Goddess of Greenton and queen of Chon’s dreams and imagination, crying. He thought of the lake of tears the people of Greenton were crying at that moment and was shocked. And shamed even further when he didn’t feel the warm stuff on his own face.

He sat at the register in silence. Through the store’s windows, he looked at a Greenton that was emptier, deader than he had ever experienced it before. He thought of the last time he’d seen the Johns. Araceli was sitting across Mejia’s lap on the tailgate of his father’s truck. Robison was sitting at the other end of the tailgate, entertaining a group of girls. The girls claimed to be friends, but were strategically elbowing each other away from the single John with malicious words told out of smiling mouths. They hungered for their sisters’ blood and the bragging rights that being with Robison on graduation night, the very weekend he was set to leave town, would have afforded them.

There was a huge circle of cars around the fire pit at the Saenz ranch that night, all of them driven there by high school students who had known the Johns as classmates and teammates and all of whom would be embraced and regarded as old friends if they ran into them on some city street in the surely glorious future. That said, the Johns were left alone—not necessarily placed in the limelight, but looked at enviously from a distance as they always had been at Greenton High and in town.

Chon and Henry were walking from a trip to the keg trough when Chon was summoned.

“Hey Dodge-nasty,” Robison shouted from his Chevy throne.

Chon looked at Henry. Henry shrugged. Chon made his way over to the truck.

“You really pulled through with the beer,” Robison said, raising his plastic cup.

Chon had gone against his better judgment in providing access to the night’s spirits. Though he didn’t have a problem selling beer to minors, he had never sold anyone underage so much—three kegs that had gone skunky from having been dropped, rolled, and kicked from one end of the Pachanga’s walk-in to the other. Chon knew that he could be fired, even arrested, if anything bad happened as a result of the beer he’d sold. He knew that every time he sold a six-pack to his contemporaries for ten dollars and kept the change.

“Didn’t Jesus say, ‘Drink up, folks,’—or something like that—at a wedding? So, you know, it was the Christian thing to do,” Chon said, looking over at Araceli.

“Hi Chon,” she said, with a little wave of her fingers. Mejia gave him a nod. This was why Chon had sold the kegs, this very exchange here.

“Yeah, man. Jesus. You’re a pretty weird guy, you know that, Dodge-nasty?” Robison said. He was drunk.

“You know what, Robe? This is the first time someone’s ever told me that when it didn’t sound like they were trying to be mean,” Chon answered back, trying his best to stare Araceli down, but out of the corner of his eyes.

“Hot damn, Dodge-nasty. You know how to make a guy feel good about himself,” Robison shouted. His crowd of girls all roared with laughter.

“Hot damn, Robe, that’s what I’m trying to tell you.”

Robison gave Chon a pound on the shoulder.

“Alright, well, good luck in Austin,” Chon said.

“Yes sir. And good luck to you here in Greenton,” Robison said, not intending to be ironic.

Chon’s eyes drifted past Araceli’s in a deliberate show that took all of the will power he had. They met John Mejia’s.

Standing there, face-to-face with his nemesis, Chon worked to convince himself that he and Mejia weren’t too different from each other. Mejia wasn’t better looking—at least not by leaps and bounds—than Chon. He had an athlete’s build, sure, but a lean teenage baseball player’s. All that separated them was a God-given and determinedly honed skill on the diamond—that and a future at a university in a city Chon couldn’t even picture in his head outside of images of clock towers and capitol buildings he’d seen in books. And a present with the only person worth wanting in a one-stoplight town built on cattle and railroads and killed by bypasses and super-ranches.

“Good luck,” Chon said.

Mejia gave him a nod and took a drink of his beer. As Chon walked away, Mejia told Araceli something that made her laugh. A fire burned inside Chon that made him wish things he would come to regret in a few short days.

The clock read 12:13 when Henry got back to The Pachanga. Chon was sitting in the dark in front of the store, unable to lock up because he’d given his keys to his best friend.

“You’re late,” he said when Henry got out of the car. He took the keys and caught a whiff of Henry. “And you’re drunk. Where’ve you been?”

“Flojo’s, man. Half the town is there, the other half is at church,” Henry said opening the passenger door to the Dodge-nasty. He let his body fall into the car, ass-first.

“You mean you were drinking at Flojo’s?” he asked Henry when he got in the car.

“Yeah man, they were letting anyone in. The sheriff was even there getting pedo. We had all posted up at the Robison place, the whole town. Then Goyo Mejia got there to be with his parents. I mean, you think everyone was wrecked before… When he got there, his mom came out to the porch to meet him and she, like, fell into his arms. That totally tore everyone up. He just stood there with her crying on him for so long he had to crouch down under her weight. His dad had to come out and help her up and into the house.”

They sat there in the parking lot of The Pachanga, the car not turned on, Henry’s story fogging up the car’s windows.

“After about an hour, Goyo came out and asked everyone to leave. He said that his parents and the Robisons were going through a rough time and had asked if we could leave them alone to ‘hurt over their sons.’ He said it like that. He wasn’t even crying, man. His face hadn’t seen a tear all day.

“By that time the whole sidewalk in front of the house was covered in candles. Man, I can’t even think of how so many candles got there so fast. That stretch of Viggie doesn’t have a streetlight, you know? The whole street was lit with candles. The sidewalk was covered in front of their place, so they just kept putting them in front of other houses. They almost reach to your house. Anyway, everyone left. No one said where they were going, but half ended up at Flojo’s and the other half at the church.”

Chon waited for Henry to tell him more. But Henry was done. He just sat there, his hands over his eyes, breath coming heavily out of his nostrils. Chon turned the car on and drove him home.

He took Mesquite from Henry’s house, a street that, along with Sigrid, served as the east end of Greenton’s east-west bookends. A few blocks from Viggie, Chon could see the town’s church strangely active. Half of Greenton must have been there, looking up at the cross with their hands clasped in prayer (like a button that has to be held down on a walkie-talkie for any correspondence to be transmitted), asking God, asking the beaten-bloody Jew on the cross—asking them both at the same time—why?

He went back over to Main Street. There was a truck pulled onto the sidewalk—like its driver had tried to park perpendicular to it and then drove right on ahead. Chon might have assumed this was one of the Flojo’s loaded congregants if he hadn’t seen someone, presumably the truck’s owner, standing on the roof of the cab. Chon slammed the brakes, backed into a two-point turn, and drove toward whoever was caving in the roof of his truck.

He put the Dodge-nasty in park, rolled down his window, and was about to shout the man down when he saw it was Goyo Mejia, indeed drunk, clinging to the telephone pole he was parked next to, tiptoeing up, just inches below the bottom right quadrant of the banner that had been hung for his little brother and his little brother’s best friend.

“Hey,” was all Chon managed to say. The first half of the H was loud enough to be heard, but he let the e and the y die in a downward glissandoing diminuendo, like a trombonist running out of breath and letting his instrument’s slide slip from his hand down to the ground.

Goyo was trying to stretch himself up the pole. Chon got out of his car to make his presence known, hoping that might make a difference. The danger of the situation had Chon standing on his toes, every muscle in his legs tense. When Goyo’s balance would tip this way or that Chon would give a start in that direction, like he did at so many routine grounders in his Little League days, with about the same, if not less, efficacy.

Suddenly Goyo gave a shout of frustration and punched at the telephone pole, which had years of nails and staples in it announcing so many yard sales and church Jamaicas and lost pets. Then he gave another shout, this one out of pain. He fell to his knee, still on the truck’s roof, and clutched at his bloody fist. Chon watched Goyo shift his focus from fist to banner, back to fist, then back again. Then he let go of his hand, laid both hands palm-side down on the roof of the truck, righted his stance, touched down and gave a leap.

Chon watched in awe. It was far more graceful a leap than Chon could have ever executed, drunk or otherwise. Goyo seemed to float in air, ascending inch by inch toward the night sky. He caught onto the banner, but it was secured to the poles so well that when the right side came down, the left still held. That changed what would have been an up/down trajectory for Goyo to an outward pull like Tarzan swinging on a vine and bought him in a belly flop onto the bed of his truck. A less determined, less inebriated man would have let go of the banner. But Goyo Mejia, clinging to a relic of his brother’s life that might otherwise have been taken by another person, held on with his bloody hand.

Half of the banner ended up in the bed of the truck with Goyo. The other half was splayed across Main Street. Chon heard a madman’s laughter, replaced quickly by the loud sobs of a person who had either broken his ribs or lost his brother. Probably both. But Goyo couldn’t have been hurt too badly because he began reeling what was left of the banner into the truck. Chon got in his car then and left, hoping that Goyo wouldn’t remember that he’d had an audience, that someone had seen him at his whisky-soaked, grief-stricken worst.

The house was empty when Chon arrived. Just like Henry said, candles lit his way home. In the time it took Chon to drop his friend off and bear witness to Goyo Mejia’s freefall, the candles had crossed his front yard and were making their way to Sigrid, if not all the way to Laredo and Mexico beyond. Chon got in the shower wondering if his parents and brother were among the half of town praying to a cross or the other half praying to the bottom of a glass.

He lay down in bed thinking, as he always did—but in a totally different way—of Araceli. He tried to imagine how she was hurting. He thought of how he would feel if she died, but he knew that it wasn’t the same thing. His obsession with her wasn’t the same thing as what she shared with John. He tried to think how he would feel if he lost his parents or his brother, but knew, without really knowing, that this wasn’t the same thing as losing someone you choose to love who chooses to love you back.

Then he gave up trying her hurt on for size. He knew she was hurting, and that was enough. He wished he could tear open her being and kiss her soul in ways sweeter and more loving than he had previously wished he could kiss her mouth or her breasts or her anything and her everything. He said a small prayer of his own for the Johns and their families.

He fell asleep that night having solved the riddle of nearly every sleepless night before then: he thought of Araceli without John Mejia muddying the picture. All he had to do, it turns out, was to think of her for her own sake—without thrusting upon her the weight of his desires and expectations—to see her as someone who could need and hurt and want and lose just like he could.

Two days later, the memorial service had to be moved from the Greenton Funeral Home to the school gym to accommodate the expected turnout. Coach Gallegos, the man the Johns had taken to regional tournaments in football and a state tournament in baseball, said a few words about the heart the Johns displayed on the field of play. Mrs. Salinas spoke about a Mejia most of them didn’t know, about the poetry he wrote and how he helped tutor his best friend and had sworn to do so through a tough academic life. “They had been thinking about academics at UT!” she said emphatically.

Dan McReynolds, who did the weekly football season addendum to the ten o’clock news—“The Friday Night Blitz”—drove in from Corpus and was the keynote speaker of sorts. He had been a fan of the Johns’ style since he first ran highlights of them during their freshman year. It was through this show that the boys had become regional celebrities, especially when McReynolds began running tape of the boys’ famous conferences at the line of scrimmage. He even began covering the Greyhounds baseball team during the spring, not just during the playoffs as was usually the case for AA teams from a town that made up so small a portion of KIII’s viewership. It all paid off when he was in Austin to cover the state playoffs during the Johns’ junior year. Greenton and AAAAA Corpus Christi Moody both lost in their respective semis. He did an exclusive interview with the boys that weekend and another when he came to Greenton to cover their signing with UT a few months prior to their deaths. During that interview, they made no show of lining up three different college caps and selecting one, as was the custom for such signings. In fact, they wore burnt orange for the occasion.

He talked about the young men he’d had the pleasure and good fortune of meeting. He’d become friends with them. He said that he had planned to cover them through college and the pros, sports or not, for the rest of his career. He gave a speech with as many sports analogies as he could fit in—he said the boys were running an option each with hands on the ball, each blocking for the other. He said that heaven was the end zone. He said that now they were in the stands cheering the rest of us on.

Chon listened and clapped along with everyone else. He had arrived early for the service, but already the gym was standing room only. He stood in back and, tall as he was, could not see the front rows of the service, where he assumed Araceli would be.

Throughout the service, the somber tone of the proceedings was disturbed by the sound of hyena-cackle laughing. People in the back of the gym where Chon was were exchanging confused looks and shaking their heads in disapproval. Single file lines formed on either side of the gym, leading up to where the Robisons and Mejias sat. When Chon got close to the front, he could see that the strange high-pitched sound wasn’t laughter, but Julie Mejia’s wails of grief.

Chon was glad to see that there were not two closed caskets at the front of the gym when he got there. They had been left at the funeral home. There were only three very large pictures—one of each John’s yearbook photos at either end of the stage and one of them when they had beaten Pleasanton to earn a trip to State their junior year. They each had an arm around the other. With their free hands they held up #1s.

Arn Robison and Andres Mejia were making an effort to shake the hand of every mourner who—out of respect or macabre curiosity—had taken a place in line to give their condolences. Angie Robison gave nods to people she knew and hugs to people she cared about and ignored the rest. Julie Mejia just cackled, clutching the arm of the son who was still with her. Goyo sat in a black suit and sunglasses, wiping his mother’s tears and caressing her face with his swollen right hand. Patchwork sutures on his fist stuck out ever so slightly, like tiny shoelaces that needed to be tied.

Chon shook both fathers’ hands, telling them he was so sorry. He had come from audience left, meaning he met Arn Robison first. When he got to Andres Mejia, he saw the Monsevais family sitting behind the Mejias. Henry was with his father, there to comfort his uncle and aunt who acted as though they’d lost one of their own because, really, they had. Conspicuously—and to Chon’s great disappointment—Araceli wasn’t there.

Sympathetic though he was to the families of the deceased, it was going to take more than a tragedy to quench his obsession. He still wanted to comfort Araceli, to make her feel better. He was removed from the initial shock of the Johns’ death, from the reality of life’s fragility and preciousness and whatever. His mind had wandered to more familiar selfish territory. He wanted to comfort her. He wanted to make her feel better. He wanted to save the day, to be her Band-Aid, her hero, to fill the roughly John-sized, boyfriend-sized void left in her heart.

He was tired from having closed the store the night before and having had to open up at five that morning because Rocha called in sick and Ana didn’t answer her phone when Art called to ask her to cover. There was a bottleneck leaving the student lot. It was only 1:30 in the afternoon though. Chon would have time to go home, shower, and get to work on time. But he wouldn’t get any sleep before going in to work.

He went to the funeral the next day with his family, even though he’d heard from Henry that Araceli wouldn’t be there either. It was as well-attended as the memorial service. People stood in the wings, vestibule, and stairs leading to the church. The Gonzales family arrived an hour and a half early, affording them a small stretch of the pew in the farthest back corner of the church. They watched two caskets carried into church, an experience Chon hadn’t expected to affect him as it did—he became lightheaded and would have fallen down if he weren’t already sitting. They heard Father Tom’s sermon and a Gospel reading, punctuated by Julie Mejia’s crazy crying. Then the caskets were carried back out and loaded into hearses. The mourners got into their cars and followed the procession through town to the Greenton cemetery. Not Chon, though. He turned the Dodge-nasty left when all of the other cars turned right. He had come to church, having dressed in a shirt and tie for the second day in a row, and paid his respects to the Johns without any hope in the world of seeing Araceli. This gesture was enough to convince Chon, as he was sure it convinced his family and would convince Araceli if it came up, that his sympathy was sincere. He’d done his politicking and point proving. He didn’t need to see a couple of mahogany boxes lowered into the ground.