Читать книгу My Grandmother's Hands - Resmaa Menakem - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

YOUR BODY AND BLOOD

“No one ever talks about the moment you found that you were white. Or the moment you found out you were black. That’s a profound revelation. The minute you find that out, something happens. You have to renegotiate everything.”

TONI MORRISON

“History is not the past, it is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.”

JAMES BALDWIN

“There is deep wisdom within our very flesh, if we can only come to our senses and feel it.”

ELIZABETH A. BEHNKE

“People don’t realize what’s really going on in this country. There are a lot of things that are going on that are unjust. People aren’t being held accountable . . . This country stands for freedom, liberty, and justice for all. And it’s not happening for all right now.”

COLIN KAEPERNICK

When I was a boy I used to watch television with my grandmother. I would sit in the middle of the sofa and she would stretch out over two seats, resting her legs in my lap. She often felt pain in her hands, and she’d ask me to rub them in mine. When I did, her fingers would relax, and she’d smile. Sometimes she’d start to hum melodically, and her voice would make a vibration that reminded me of a cat’s purr.

She wasn’t a large woman, but her hands were surprisingly stout, with broad fingers and thick pads below each thumb. One day I asked her, “Grandma, why are your hands like that? They ain’t the same as mine.”

My grandmother turned from the television and looked at me. “Boy,” she said slowly. “That’s from picking cotton. They been that way since long before I was your age. I started working in the fields sharecroppin’ when I was four.”

I didn’t understand. I’d helped plant things in the garden a few times, but my own hands were bony and my fingers were narrow. I held up my hands next to hers and stared at the difference.

“Umm hmm,” she said. “The cotton plant has pointed burrs in it. When you reach your hand in, the burrs rip it up. When I first started picking, my hands were all torn and bloody. When I got older, they got thicker and thicker, until I could reach in and pull out the cotton without them bleeding.”

My grandmother died last year. Sometimes I can still feel her warm, thick hands in mine.

For the past three decades, we’ve earnestly tried to address white-body supremacy in America with reason, principles, and ideas—using dialogue, forums, discussions, education, and mental training. But the widespread destruction of Black bodies continues. And some of the ugliest destruction originates with our police. Why is there such a chasm between our well-intentioned attempts to heal and the ever-growing number of dark-skinned bodies who are killed or injured, sometimes by police officers?

It’s not that we’ve been lazy or insincere. But we’ve focused our efforts in the wrong direction. We’ve tried to teach our brains to think better about race. But white-body supremacy doesn’t live in our thinking brains. It lives and breathes in our bodies.

Our bodies have a form of knowledge that is different from our cognitive brains. This knowledge is typically experienced as a felt sense of constriction or expansion, pain or ease, energy or numbness. Often this knowledge is stored in our bodies as wordless stories about what is safe and what is dangerous. The body is where we fear, hope, and react; where we constrict and release; and where we reflexively fight, flee, or freeze. If we are to upend the status quo of white-body supremacy, we must begin with our bodies.

New advances in psychobiology reveal that our deepest emotions—love, fear, anger, dread, grief, sorrow, disgust, and hope—involve the activation of our bodily structures. These structures—a complex system of nerves—connect the brainstem, pharynx, heart, lungs, stomach, gut, and spine. Neuroscientists call this system the wandering nerve or our vagus nerve; a more apt name might be our soul nerve. The soul nerve is connected directly to a part of our brain that doesn’t use cognition or reasoning as its primary tool for navigating the world. Our soul nerve also helps mediate between our bodies’ activating energy and resting energy.

This part of our brain is similar to the brains of lizards, birds, and lower mammals. Our lizard brain only understands survival and protection. At any given moment, it can issue one of a handful of survival commands: rest, fight, flee, or freeze.3 These are the only commands it knows and the only choices it is able to make.

White-body supremacy is always functioning in our bodies. It operates in our thinking brains, in our assumptions, expectations, and mental shortcuts. It operates in our muscles and nervous systems, where it routinely creates constriction. But it operates most powerfully in our lizard brains. Our lizard brain cannot think. It is reflexively protective, and it is strong. It loves whatever it feels will keep us safe, and it fears and hates whatever it feels will do us harm.

All our sensory input has to pass through the reptilian part of our brain before it even reaches the cortex, where we think and reason. Our lizard brain scans all of this input and responds, in a fraction of a second, by either letting something enter into the cortex or rejecting it and inciting a fight, flee, or freeze response. This mechanism allows our lizard brain to override our thinking brain whenever it senses real or imagined danger. It blocks any information from reaching our thinking brain until after it has sent a message to fight, flee, or freeze.

In many situations, our thinking brain is smart enough to be careful and situational. But when there appears to be danger, our lizard brain may say to the thinking brain, “Screw you. Out of my way. We’re going to fight, flee, or freeze.”

Many of us picture our thinking brain as a tiny CEO in our head who makes important executive decisions. But this metaphor is misguided: Our cortex doesn’t get the opportunity to have a thought about any piece of sensory input unless our lizard brain lets it through. And in making its decision, our reptilian brain always asks the same question: Is this dangerous or safe?

Remember that dangerous can mean a threat to more than just the well being of our body. It can mean a threat to what we do, say, think, care about, believe in, or yearn for. When it comes to safety, our thinking mind is third in line after our body and our lizard brain. That’s why when we put a hand on a hot frying pan, the hand jerks away instantly, while our thinking brain goes, What the hell just happened? OW! THAT SHIT IS HOT! It’s also why you might have the impulse to throw the pan across the kitchen—even though doing so won’t help you.

The body is where we live. It’s where we fear, hope, and react. It’s where we constrict and relax. And what the body most cares about are safety and survival. When something happens to the body that is too much, too fast, or too soon, it overwhelms the body and can create trauma.

Contrary to what many people believe, trauma is not primarily an emotional response. Trauma always happens in the body. It is a spontaneous protective mechanism used by the body to stop or thwart further (or future) potential damage.

Trauma is not a flaw or a weakness. It is a highly effective tool of safety and survival. Trauma is also not an event. Trauma is the body’s protective response to an event—or a series of events—that it perceives as potentially dangerous. This perception may be accurate, inaccurate, or entirely imaginary. In the aftermath of highly stressful or traumatic situations, our soul nerve and lizard brain may embed a reflexive trauma response in our bodies. This happens at lightning speed.

An embedded trauma response can manifest as fight, flee, or freeze—or as some combination of constriction, pain, fear, dread, anxiety, unpleasant (and/or sometimes pleasant) thoughts, reactive behaviors, or other sensations and experiences. This trauma then gets stuck in the body—and stays stuck there until it is addressed.

We can have a trauma response to anything we perceive as a threat, not only to our physical safety, but to what we do, say, think, care about, believe in, or yearn for. This is why people get murdered for disrespecting other folks’ relatives or their favorite sports teams. It’s also why people get murdered when other folks imagine a relative or favorite team was disrespected. From the body’s viewpoint, safety and danger are neither situational nor based on cognitive feelings. Rather, they are physical, visceral sensations. The body either has a sense of safety or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t, it will do almost anything to establish or recover that sense of safety.

Trauma responses are unique to each person. Each such response is influenced by a person’s particular physical, mental, emotional, and social makeup—and, of course, by the precipitating experiences themselves. However, trauma is never a personal failing, and it is never something a person can choose. It is always something that happens to someone.

A traumatic response usually sets in quickly—too quickly to involve the rational brain. Indeed, a traumatic response temporarily overrides the rational brain. It’s like when a computer senses a virus and responds by shutting down some or all of its functions. (This is also why, when mending trauma, we need to proceed slowly, so that we can uncover the body’s functions without triggering yet another trauma response.)

As mentioned earlier, trauma is also a wordless story our body tells itself about what is safe and what is a threat. Our rational brain can’t stop it from occurring, and it can’t talk our body out of it. Trauma can cause us to react to present events in ways that seem wildly inappropriate, overly charged, or otherwise out of proportion. Whenever someone freaks out suddenly or reacts to a small problem as if it were a catastrophe, it’s often a trauma response. Something in the here and now is rekindling old pain or discomfort, and the body tries to address it with the reflexive energy that’s still stuck inside the nervous system. This is what leads to over-the-top reactions.

Such overreactions are the body’s attempt to complete a protective action that got thwarted or overridden during a traumatic situation. The body wanted to fight or flee, but wasn’t able to do either, so it got stuck in freeze mode. In many cases, it then develops strategies around this “stuckness,” including extreme reactions, compulsions, strange likes and dislikes, seemingly irrational fears, and unusual avoidance strategies. Over time, these can become embedded in the body as standard ways of surviving and protecting itself. When these strategies are repeated and passed on over generations, they can become the standard responses in families, communities, and cultures.

One common (and often overlooked) trauma response is what I called trauma ghosting. This is the body’s recurrent or pervasive sense that danger is just around the corner, or something terrible is going to happen any moment.

These responses tend to make little cognitive sense, and the person’s own cognitive brain is often unaware of them. But for the body they make perfect sense: it is protecting itself from repeating the experience that caused or preceded the trauma.

In other cases, people do the exact opposite: they reenact (or precipitate) situations similar to the ones that caused their trauma. This may seem crazy or neurotic to the cognitive mind, but there is bodily wisdom behind it. By recreating such a situation, the person also creates an opportunity to complete whatever action got thwarted or overridden. This might help the person mend the trauma, create more room for growth in his or her body, and settle his or her nervous system.4

However, the attempt to reenact the event often simply repeats, re-inflicts, and deepens the trauma. When this happens repeatedly over time, the trauma response can look like part of the person’s personality. As years and decades pass, reflexive traumatic responses can lose context. A person may forget that something happened to him or her—and then internalize the trauma responses. These responses are typically viewed by others, and often by the person, as a personality defect. When this same strategy gets internalized and passed down over generations within a particular group, it can start to look like culture. Therapists call this a traumatic retention.

Many African Americans know trauma intimately—from their own nervous systems, from the experiences of people they love, and, most often, from both. But African Americans are not alone in this. A different but equally real form of racialized trauma lives in the bodies of most white Americans. And a third, often deeply toxic type of racialized trauma lives and breathes in the bodies of many of America’s law enforcement officers.

All three types of trauma are routinely passed on from person to person and from generation to generation. This intergenerational transmission—which, more aptly and less clinically, I call a soul wound5—occurs in multiple ways:

• Through families in which one family member abuses or mistreats another.

• Through unsafe or abusive systems, structures, institutions, and/or cultural norms.

• Through our genes. Recent work in human genetics suggests that trauma is passed on in our DNA expression, through the biochemistry of the human egg, sperm, and womb.

This means that no matter what we look like, if we were born and raised in America, white-body supremacy and our adaptations to it are in our blood. Our very bodies house the unhealed dissonance and trauma of our ancestors.

This is why white-body supremacy continues to persist in America, and why so many African Americans continue to die from it. We will not change this situation through training, traditional education, or other appeals to the cognitive brain. We need to begin with the body and its relation to trauma.

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates exposed the longstanding and ongoing destruction of the Black body in America. That destruction will continue until Americans of all cultures and colors learn to acknowledge the inherited trauma of white-body supremacy embedded in all our bodies. We need to metabolize this trauma; work through it with our bodies (not just our thinking brains); and grow up out of it. Only in this way will we at last mend our bodies, our families, and the collective body of our nation. The process differs slightly for Black folks, white folks, and America’s police. But all of us need to heal—and, with the right guidance, all of us can. That healing is the purpose of this book.

This book is about the body. Your body.

If you’re African American, in this book you’ll explore the trauma that is likely internalized and embedded in it. You’ll see how multiple forces—genes, history, culture, laws, and family—have created a long bloodline of trauma in African American bodies.

It doesn’t mean we’re defective. In fact, it means just the opposite: something happened to us, something we can heal from. We survived because of our resilience, which was also passed down from one generation to the next.

This book presents some profound opportunities for healing and growth. Some of these are communal healing practices our African American and African ancestors developed and adapted; others are more recent creations. All of these practices foster resilience in our bodies and plasticity in our brains. We’ll use these practices to recognize the trauma in our own bodies; to touch it, heal it, and grow out of it; and to create more room for growth in our nervous systems.

White-body supremacy also harms people who do not have dark skin. If you’re a white American, your body has probably inherited a different legacy of trauma that affects white bodies—and, at times, may rekindle old flight, flee, or freeze responses. This trauma goes back centuries—at least as far back as the Middle Ages—and has been passed down from one white body to another for dozens of generations.

White bodies traumatized each other in Europe for centuries before they encountered Black and red bodies. This carnage and trauma profoundly affected white bodies and the expressions of their DNA. As we’ll see, this historical trauma is closely linked to the development of white-body supremacy in America.

If you’re a white American, this book will offer you a wealth of practices for mending this trauma in your own body, growing beyond it, and creating more room in your own nervous system. I urge you to take this responsibility seriously. As you’ll discover, it will help create greater freedom and serenity for all of us.

Courtesy of white-body supremacy, a deep and persistent condition of chronic stress also lives in the bodies of many members of the law enforcement profession, regardless of their skin color. If you’re a policeman or policewoman, you’ve almost certainly either suffered or observed this third type of trauma. This book offers you a vital path of healing as well.

While I hope everyone who reads this book will fully heal his or her trauma, I know this hope isn’t realistic. Many readers will learn something from this book, and perhaps practice some of the activities in it, but eventually will stop reading or turn away. If that’s ultimately what you do, it doesn’t mean you haven’t benefited. You may still have created a little extra room in your nervous system for flow, for resilience, for coherence, for growth, and, above all, for possibility. That extra room may then get passed on to your children or to other people you encounter.

In today’s America, we tend to think of healing as something binary: either we’re broken or we’re healed from that brokenness. But that’s not how healing operates, and it’s almost never how human growth works. More often, healing and growth take place on a continuum, with innumerable points between utter brokenness and total health. If this book moves you even a step or two in the direction of healing, it will make an important difference.

In fact, in this book you’ll meet some people who have not fully healed their trauma, but who have nevertheless made strides in that direction and who have deepened their lives and the lives of others as a result.

Years as a healer and trauma therapist have taught me that trauma isn’t destiny. The body, not the thinking brain, is where we experience most of our pain, pleasure, and joy, and where we process most of what happens to us. It is also where we do most of our healing, including our emotional and psychological healing. And it is where we experience resilience and a sense of flow.

Over the past decade or so, therapists have become increasingly aware of the importance of the body in this mending. Until recently, psychotherapy (commonly shortened to therapy) was what we now call talk therapy or cognitive therapy or behavioral therapy.6 The basic strategy behind these therapies is simple: you, a lone individual, come to my office; you and I talk; you have insights, most of which are cognitive and/or behavioral; and those cognitive and/or behavioral insights help you heal. The problem is that this turns out not to be the only way healing works. Recent studies and discoveries increasingly point out that we heal primarily in and through the body, not just through the rational brain. We can all create more room, and more opportunities for growth, in our nervous systems. But we do this primarily through what our bodies experience and do—not through what we think or realize or cognitively figure out.

In addition, trauma and healing aren’t just private experiences. Sometimes trauma is a collective experience, in which case our approaches for mending must be collective and communal as well.

People in therapy can have insights galore, but may stay stuck in habitual pain, harmful trauma patterns, and automatic reactions to real or perceived threats. This is because trauma is embedded in their bodies, not their cognitive brains. That trauma then becomes the unconscious lens through which they view all of their current experiences.

Often this trauma blocks attempts to heal it. Whenever the body senses the opportunity—and the challenge—to mend, it responds by fighting, fleeing, or freezing. (In therapy, this might involve a client getting angry, going numb and silent, or saying, “I don’t want to talk about that.”)

As a therapist, I’ve learned that when trauma is present, the first step in healing almost always involves educating people on what trauma is. Trauma is all about speed and reflexivity—which is why, in addressing trauma, each of us needs to work through it slowly, over time. We need to understand our body’s process of connection and settling. We need to slow ourselves down and learn to lean into uncertainty, rather than away from it. We need to ground ourselves, touch the pain or discomfort inside our trauma, and explore it—gently. This requires building a tolerance for bodily and emotional discomfort, and learning to stay present with—rather than trying to flee—that discomfort. (Note that it does not necessarily mean exploring, reliving, or cognitively understanding the events that created the trauma.) With practice, over time, this enables us to be more curious, more mindful, and less reflexive. Only then can growth and change occur.

There’s some genuine value to talk therapy that focuses just on cognition and behavior. But on its own, especially when trauma is in the way, it won’t be enough to enable you to mend the wounds in your heart and body.

In America, nearly all of us, regardless of our background or skin color, carry trauma in our bodies around the myth of race. We typically think of trauma as the result of a specific and deeply painful event, such as a serious accident, an attack, or the news of someone’s death. That may be the case sometimes, but trauma can also be the body’s response to a long sequence of smaller wounds. It can be a response to anything that it experiences as too much, too soon, or too fast.

Trauma can also be the body’s response to anything unfamiliar or anything it doesn’t understand, even if it isn’t cognitively dangerous. The body doesn’t reason; it’s hardwired to protect itself and react to sensation and movement. When a truck rushes by at sixty miles an hour and misses your body by an inch, your body may respond with trauma as deep and as serious as if it had actually been sideswiped. When watching a horror film, you may jump out of your seat even though you know it’s just a movie. Your body acts as if the danger is real, regardless of what your cognitive brain knows. The body’s imperative is to protect itself. Period.

Trauma responses are unpredictable. Two bodies may respond very differently to the same experience. If you and a friend are at a Fourth of July celebration and a firecracker explodes at your feet, your body may forget about the incident within minutes, while your friend may go on to be terrified by loud, sudden noises for years afterward. When two siblings suffer the same childhood abuse, one may heal fully during adolescence, while the other may get stuck and live with painful trauma for decades. Some Black bodies demonstratively suffer deep traumatic wounds from white-body supremacy, while other bodies appear to be less affected.

Trauma or no trauma, many Black bodies don’t feel settled around white ones, for reasons that are all too obvious: the long, brutal history of enslavement and subjugation; racial profiling (and occasionally murder) by police; stand-your-ground laws; the exoneration of folks such as George Zimmerman (who shot Trayvon Martin), Tim Loehmann (who shot Tamir Rice), and Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam (who murdered Emmett Till); outright targeted aggression; and the habitual grind of everyday disregard, discrimination, institutional disrespect, over-policing, over-sentencing, and micro-aggressions.7

As a result, the traumas that live in many Black bodies are deep and persistent. They contribute to a long list of common stress disorders in Black bodies, such as post-traumatic stress disorder8 (PTSD), learning disabilities, depression and anxiety, diabetes, high blood pressure, and other physical and emotional ailments.

These conditions are not inevitable. Many Black bodies have proven very resilient, in part because, over generations, African Americans have developed a variety of body-centered responses to help settle their bodies and blunt the effects of racialized trauma. These include individual and collective humming, rocking, rhythmic clapping, drumming, singing, grounding touch, wailing circles, and call and response, to name just a few.

The traumas that live in white bodies, and the bodies of public safety professionals of all races, are also deep and persistent. However, their origins and nature are quite different. The expression of these traumas is often an immediate, seemingly out-of-the-blue fight, flee, or freeze response, a response that may be reflexively triggered by the mere presence of a Black body—or, sometimes, by the mere mention of race or the term white supremacy or white-body supremacy.

Many English words are loaded or slippery, especially when it comes to race. So let me define some terms.

When I say the Black body or the African American body, it’s shorthand for the bodies of people of African descent who live in America, who have largely shaped its culture, and who have adapted to it. If you’re a Kenyan citizen who has never been to the United States, or a new arrival in America from Cameroon or Haiti or Argentina, some of this book may not apply to you—at least not obviously. Aside from your (perhaps) dark skin, you may not recognize yourself in these pages. (I’m not suggesting that non-Americans without white skin aren’t routinely affected by the global reach of white-body supremacy, only that some of these folks have been fortunate enough to have little or no personal experience with America’s version of racialized trauma. Others have strong resiliency factors that have mitigated some of the effects of white-body supremacy in their lives.)

When I say the white body, it’s shorthand for the bodies of people of European descent who live in America, who have largely shaped and adapted to its culture, and who don’t have dark skin. The term white body lacks precision, but it’s short and simple. If you’re a member of this group, you’ll recognize it when I talk about the white body’s experience.

When I say police bodies, it’s shorthand for the bodies of law enforcement professionals, regardless of their skin color. These professionals include beat cops, police detectives, mall security guards, members of SWAT teams, and the police chiefs of big cities, suburbs, and small towns.

These categories provide ways of communicating, not boxes for anyone to be forced into. It’s possible that none of them fits you. Or maybe you fit into more than one. Don’t try to squeeze yourself into one in particular. Instead, adapt everything you read in this book as your body instructs you to. It will tell you what matches its experience and how to work with its energy and wordless stories.

Maybe you’re an African American whose body, for whatever reason, is entirely free of racialized trauma. Or maybe you’re a white American or police officer whose body doesn’t constrict in the presence of Black bodies, and who can stay settled and present in your own discomfort when the subject of race arises. Either way, I encourage you to try out the body-centered activities in this book. Whether or not you yourself are personally wounded by white-body supremacy, working with these exercises and letting them sink into you will help you build your self-awareness, deepen your capacity for empathy, and create more room for growth in your nervous system.

I’m not the first to recognize the key role of the destruction, restriction, and abuse of the Black body in American history. In Killing the Black Body, Dorothy Roberts wrote of centuries-long efforts by white people to control the wombs of African American women. A decade later, in Black Bodies, White Gazes, George Yancy explored the confiscation of Black bodies by white culture. In Stand Your Ground, Kelly Brown Douglas examined many social and theological issues related to the African American body. Meri Nana-Ama Danquah’s The Black Body collected thirty writers’ reflections on the role of the Black body in America. James Baldwin, Richard Wright, bell hooks, Teju Cole, and others have written eloquently on the subject of African American bodies. As I worked on this book, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, an examination of the systematic destruction of the Black body in America, reached the number one spot on the New York Times bestseller list.

All these writers are wise, loving, and profoundly observant. I’m deeply grateful for their contributions, which have helped to create the foundation on which this book is built. But I come at the subject from a different direction.

Some of these writers—Yancy, Roberts, hooks, Douglas—are academics and philosophers, while others—Coates, Baldwin, Wright, Danquah, Cole—are literary authors. With piercing insight and eloquence, they reveal what white-body supremacy tries to keep hidden, and lay bare what many of us habitually overlook or cover up. In this book, I accept with gratitude the baton that these wise writers have handed to me.

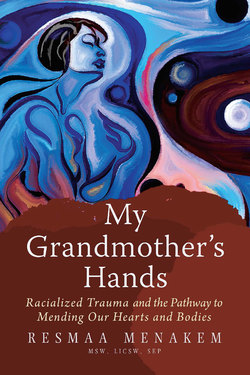

My Grandmother’s Hands is a book of healing. I’m a healer and trauma therapist, not a philosopher or literary stylist. My earlier book, Rock the Boat: How to Use Conflict to Heal and Deepen Your Relationship (Hazelden, 2015), is a practical guide for couples. In that book, as well as in this one, my focus is on mending psyches, souls, bodies, and relationships—and, whenever possible, families, neighborhoods, and communities.

In Part I, you’ll see how white-body supremacy gets systematically (if often unconsciously or unwittingly) embedded in our American bodies even before we are born, creating ongoing trauma and a legacy of suffering for virtually all of us.

This racialized trauma appears in three different forms—one in the bodies of white Americans, another in those of African Americans, and yet another in the bodies of police officers. The trauma in white bodies has been passed down from parent to child for perhaps a thousand years, long before the creation of the United States. The trauma in African American bodies is often (and understandably) more severe but, in historical terms, also more recent. However, each individual body has its own unique trauma response, and each body needs (and deserves) to heal.

In Part II, you’ll experience and absorb dozens of activities designed to help you mend your own trauma around white-body supremacy and create more room and opportunities for growth in your own nervous system. The opening chapters of Part II are for everyone, while later chapters focus on specific groups: African Americans, white Americans, and American police.

The chapters for African American readers grew, in part, out of my Soul Medic and Cultural Somatics workshops. I began offering these several years ago, along with workshops on psychological first aid. These provide body-centered experiences meant to help Black Americans experience their bodies, begin to recognize and release trauma, and bring some of that healing and room into the communal body.

The chapters for white readers draw partly from what I’ve learned from conducting similar workshops for white allies co-led with Margaret Baumgartner, Fen Jeffries, and Ariella Tilsen—white facilitators, conflict resolvers, and healing practitioners. The material on the community aspects of mending white bodies is supported by work I’ve done in collaboration with Susan Raffo of the People’s Movement Center and Janice Barbee of Healing Roots, both in Minneapolis.

The chapters for law enforcement officers draw from the trainings I’ve led for police officers on trauma, self-care, white-body supremacy, and creating some healing infrastructure in their departments and precincts.

Part III will give you the tools to take your healing, and your newfound knowledge and awareness, into your community. It provides some simple, structured activities for helping other people you encounter release the trauma of white-body supremacy—in your family, neighborhood, workplace, and elsewhere. Because all of us, separately and together, can be healers, I begin with tools and strategies that anyone can apply, and follow them with specific chapters for African Americans, white Americans, and police.

As every therapist will tell you, healing involves discomfort—but so does refusing to heal. And, over time, refusing to heal is always more painful.

In my therapy office, I tell clients there are two kinds of pain: clean pain and dirty pain. Clean pain is pain that mends and can build your capacity for growth.9 It’s the pain you experience when you know, exactly, what you need to say or do; when you really, really don’t want to say or do it; and when you do it anyway. It’s also the pain you experience when you have no idea what to do; when you’re scared or worried about what might happen; and when you step forward into the unknown anyway, with honesty and vulnerability.

Experiencing clean pain enables us to engage our integrity and tap into our body’s inherent resilience and coherence, in a way that dirty pain does not. Paradoxically, only by walking into our pain or discomfort—experiencing it, moving through it, and metabolizing it—can we grow. It’s how the human body works.

Clean pain hurts like hell. But it enables our bodies to grow through our difficulties, develop nuanced skills, and mend our trauma. In this process, the body metabolizes clean pain. The body can then settle; more room for growth is created in its nervous system; and the self becomes freer and more capable, because it now has access to energy that was previously protected, bound, and constricted. When this happens, people’s lives often improve in other ways as well.

All of this can happen both personally and collectively. In fact, if American bodies are to move beyond the pain and limitation of white-body supremacy, it needs to happen in both realms. Accepting clean pain will allow white Americans to confront their longtime collective disassociation and silence. It will enable African Americans to confront their internalization of defectiveness and self-hate. And it will help public safety professionals in many localities to confront the recent metamorphosis of their role from serving the community to serving as soldiers and prison guards.

Dirty pain is the pain of avoidance, blame, and denial. When people respond from their most wounded parts, become cruel or violent, or physically or emotionally run away, they experience dirty pain. They also create more of it for themselves and others.

A key factor in the perpetuation of white-body supremacy is many people’s refusal to experience clean pain around the myth of race. Instead, usually out of fear, they choose the dirty pain of silence and avoidance and, invariably, prolong the pain.

In experiencing this book, you will face some pain. Neither you nor I can know how much, and it may not show up in the place or the manner you expect. Whatever your own background or skin color, as you make your way through these pages, I encourage you to let yourself experience that clean pain in order to let yourself heal. If you do, you may save yourself—and others—a great deal of future suffering.

In Chapters Ten, Eleven, and Twelve, I’ll give you some practical tools to help your body become settled, anchored, and present within your clean pain, so that you can slowly metabolize your trauma and move through and beyond it. (I’ll also give you parallel tools to help you quickly activate your body on demand, for times when that might be necessary.)

It’s easy to assume the way people interact in twenty-first-century America is the way human beings have always interacted, at all times and in all places. Of course, this isn’t so. It’s equally easy to imagine that twenty-first-century American society is somehow fundamentally different from any other time and place in history. That isn’t so, either. Here are some things to acknowledge before we go further:

• Trauma is as ancient as human beings. In fact, it’s more ancient. Animals that were here eons before humans appeared also experience trauma in their bodies.

• Oppression, enslavement, and fear of the other are as old, and as widespread, as human civilization.

• A variety of forms of supremacy—of one group being elevated above another—have existed around the world for millennia and still exist today. Multiple forms of supremacy often intersect and compound each other, harming human beings in profoundly negative ways.

• Race is an invention—and a relatively modern one.

• My Grandmother’s Hands looks at racialized trauma in America, how that trauma gets perpetuated through white-body supremacy, and how we can heal from it. Because of its American focus, some of its insights and activities may not be appropriate for some other countries and cultures.

• White-body supremacy in America doesn’t just harm Black people. It damages everyone. Historically, it has also been especially brutal toward Native Americans, and, often, Latino Americans.

• As we’ll see, while white-body supremacy benefits white Americans in some ways, it also does great harm to white bodies, hearts, and psyches.

So far, all you know about me is that I’m a body-centered therapist who specializes in trauma work, that I lead Soul Medic and Cultural Somatics workshops, and that I’ve published a book that helps couples mend and deepen their relationships. (I’ve also published a book of guidance for emerging justice leaders.) But for you to trust me and stick with me throughout this book, you probably want to know much more. Fair enough.

I’m a longtime therapist and licensed clinical social worker in private practice. I specialize in couples’ trauma work, conflict in relationships of all kinds, and domestic violence prevention. Recently I established Cultural Somatics, an area of study and practice that applies our knowledge of trauma and resilience to history, intergenerational relationships, institutions, and the communal body. I’m also a leadership coach for emerging justice leaders. I’ve been a guest on both The Oprah Winfrey Show and Dr. Phil, where I discussed family dynamics, couples in conflict, and domestic violence. For ten years, I cohosted a radio show with US Congressman Keith Ellison on KMOJ-FM in Minneapolis. I also hosted my own show, “Resmaa in the Morning,” on KMOJ.

I’ve worked as a trainer for the Minneapolis Police Department; a trauma consultant for the St. Paul Public Schools; the director of counseling services for Tubman Family Alliance, a domestic violence treatment center in Minneapolis; the behavioral health director for African American Family Services in Minneapolis; a domestic violence counselor for Wilder Foundation; a divorce and family mediator; a social worker and consultant for the Minneapolis Public Schools; a community organizer; and a consultant for the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

For two years I served as a community care counselor for civilian contractors in Afghanistan, managing the wellness and counseling services on fifty-three US military bases. As a certified Military Family Life Consultant, I also worked with members of the military and their families on issues related to family living, deployment, and returning home.

But here’s what may be most important: I’m just like you. I’ve experienced my own trauma around white-body supremacy—and around other things as well. Sometimes white people scare me. Sometimes my African American brothers and sisters scare me. Sometimes I scare myself. But when I’m scared, I know enough to let my body tap into its inherent resilience and flow, to help it settle, and to lean into my clean pain. I also have a community of healed and healing bodies that supports me and holds me accountable.

Even though I’m law abiding and my brother is a cop, police sometimes scare me. I drive a Dodge Challenger with racing stripes, so police follow me a lot, and sometimes I get pulled over.10 I’m always friendly and polite when this happens, but I worry I’ll get the wrong officer who’s been struggling with his or her own trauma.

I was raised in a family that was sometimes stable, sometimes chaotic. My father struggled with chemical dependency and was violent at times. As a young adult, I was angry, frightened, and confused. It took me a long time to find my place in the world. Fortunately, I had a family, community, mentors, elders, and ancestors who all expected the best of me and encouraged me to grow up and heal.

I want you, and me, and all of us to heal, to be free of racialized trauma, to feel safe and secure in our bodies and in the world, and to pass on that safety and security to future generations. This book is my attempt to create more of that safety.

—BODY CENTERED PRACTICE—

Take a moment to ground yourself in your own body. Notice the outline of your skin and the slight pressure of the air around it. Experience the firmer pressure of the chair, bed, or couch beneath you—or the ground or floor beneath your feet.

Can you sense hope in your body? Where? How does your body experience that hope? Is it a release or expansion? A tightening born of eagerness or anticipation?

What specific hopes accompany these sensations? The chance to heal? To be free of the burden of racialized trauma? To live a bigger, deeper life?

Do you experience any fear in your body? If so, where? How does it manifest? As tightness? As a painful radiance? As a dead, hard spot?

What worries accompany the fear? Are you afraid your life will be different in ways you can’t predict? Are you afraid of facing clean pain? Are your worried you will choose dirty pain instead? Do you feel the raw, wordless fear—and, perhaps, excitement—that heralds change? What pictures appear in your mind as you experience that fear?

If your body feels both hopeful and afraid, congratulations. You’re just where you need to be for what comes next.

One final note: at the end of each chapter you’ll find a list of Re-memberings, which highlight the key insights from that chapter. Rememberings will help you easily recall these insights and use them for healing in a variety of ways: to re-member your ancestors, your history, and your body; to create more room and opportunities for growth in your nervous system; to build and rebuild community; and to discover or rediscover your full membership in the human community.

RE-MEMBERINGS

• White-body supremacy doesn’t live just in our thinking brains. It lives and breathes in our bodies.

• As a result, we will never outgrow white-body supremacy just through discussion, training, or anything else that’s mostly cognitive. Instead, we need to look to the body—and to the embodied experience of trauma.

• Our deepest emotions involve the activation of a single bodily structure: our soul nerve (or vagus nerve). This nerve is connected to our lizard brain, which is concerned solely with survival and protection. Our lizard brain only has four basic commands: rest, fight, flee, or freeze.

• In the aftermath of a highly stressful event, our lizard brain may embed a reflexive trauma response—a wordless story of danger—in our body. This trauma can cause us to react to present events in ways that seem out of proportion or wildly inappropriate to what’s actually going on.

• Trauma is routinely passed on from person to person—and generation to generation—through genetics, culture, family structures, and the biochemistry of the egg, sperm, and womb. Trauma is literally in our blood.

• Most African Americans know trauma intimately. But different kinds of racialized trauma also live and breathe in the bodies of most white Americans, as well as most law enforcement professionals.

• All of us need to metabolize the trauma, work through it, and grow up out of it with our bodies, not just our thinking brains. Only in this way will we heal at last, both individually and collectively.

• That healing is the purpose of this book.

• This book is about the body. Your body.

• Whether you’re a Black American, a white American, or a police officer, this book offers you profound opportunities for growth and healing.

• Trauma is not destiny. It can be healed.

• Talk therapy can help with this process, but the body is the central focus for healing trauma.

• Trauma is all about speed and reflexivity. This is why people need to work through trauma slowly, over time, and why they need to understand their own bodies’ processes of connecting and settling.

• Sometimes trauma is a collective experience, in which case the healing must be collective and communal as well.

• Trauma can be the body’s response to anything unfamiliar or anything it doesn’t understand.

• Trauma responses are unpredictable. Two bodies may respond very differently to the same stressful or painful event.

• Healing involves discomfort, but so does refusing to heal. And, over time, refusing to heal is always more painful.

• There are two kinds of pain. Clean pain is pain that mends and can build your capacity for growth. It’s the pain you feel when you know what to say or do; when you really, really don’t want to say or do it; and when you do it anyway, responding from the best parts of yourself. Dirty pain is the pain of avoidance, blame, or denial—when you respond from your most wounded parts.

3 I and some other therapists also recognize a fifth command: annihilate. The lizard brain issues this command when it senses (accurately or inaccurately) that a threat is extreme and the body’s total destruction is imminent. The annihilate command is a last-ditch effort to survive. It usually looks like sudden, extreme rage or like the attack of a provoked animal. Some therapists see annihilate as just a variant of the fight response, but I classify it separately, because annihilation energy looks and feels quite different from fighting energy. It’s the difference between a punch and a decapitation. Because fight, flee, or freeze has become such a meme, I’ll continue to use that phrase throughout the book. But in a therapy session, there are times when it’s important for the therapist to note and work with the unique energy of an annihilate response. At times, I’ll mention it again in this book as well. More generally, we would also be wise to recognize that much of what we call rage is actually unmetabolized annihilation energy.

4 If you’d like a more detailed understanding of human trauma, read Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (New York: Viking Penguin, 2014). If you’re interested in the practice of helping others heal their trauma or in addressing your own as swiftly and safely as possible, an excellent place to start is Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing Trauma Institute (SETA), traumahealing.org. I have received training from both Dr. van der Kolk and the SETA.

5 I did not invent the term soul wound. It has been around for some time, and is most often used in relation to the intergenerational and historical trauma of Native Americans. Eduardo Duran’s book on counseling with Native peoples is entitled Healing the Soul Wound (Teachers College Press, 2006). “Soul Wounds” was also the title of a 2015 conference on intergenerational and historical trauma at Stanford University.

6 These terms describe a general approach to psychological and emotional healing. They should not be confused with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which is a specific model of therapy that includes six distinct, predictable phases. CBT is widely used and has a generally good track record. However, it has also been widely disparaged, and it has been the subject of some controversy within the field. In my view, CBT’s primary limitation is the same limitation of talk therapy in general: it pays too little attention to the body.

7 Micro-aggressions are the small but relentless things people do to insult or dismiss us or deny our experience or feelings. If you’ve ever been deliberately ignored by a sales clerk, or questioned harshly and at length by a border patrol agent, or told, “I’ve never seen that happen; you must have imagined it,” you experienced a micro-aggression.

8 Although the formal, clinical term is post-traumatic stress disorder, a more accurate term would be pervasive traumatic stress disorder. Post means after, and for many Black Americans, traumatic stress is ongoing, not just something from the past.

9 The terms clean pain and dirty pain were popularized by one of my mentors, Dr. David Schnarch, and by Dr. Steven Hayer. Dr. Hayer defines and uses the terms somewhat differently than Dr. Schnarch and I do.

10 I also own a Corolla, which police follow far less often.