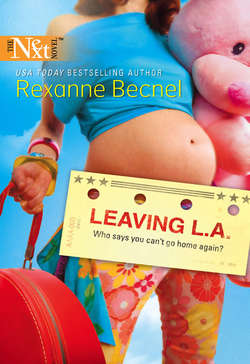

Читать книгу Leaving L.a. - Rexanne Becnel - Страница 8

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеI come from a long line of motherless daughters. I used to think of us as fatherless: my mother, my older half sister, me. But the truth is that the worst damage to us came from being essentially motherless.

That’s the conclusion I reached after six days, thirty cups of pure caffeine and two thousand miles of driving back home. Of course all that philosophical crap leached out of my head the minute I crossed the Louisiana state line. That’s when I started obsessing about what I would wear to my big reunion with my sister. I’m not proud to admit that I changed clothes three times in the last one hundred miles of my trek. The first time in a Burger King in Port Allen; the second time in a Shell station just east of Baton Rouge; and the third time on a dirt road beside a cow pasture just off Highway 1082.

Okay, I was nervous. How do you dress when you’re coming home for the first time in twenty-three years and you’re pretty sure your only sister is going to slam the door in your face—assuming she even recognizes you?

I settled on a pair of skin-tight leopard-print capris, a black Thomasina spaghetti-strap top with a built-in push-up bra, a pair of Rainbow stilettos and a black dog-collar choker with pyramid studs all around. My own personal power look: heavy metal, hot mama who’ll kick your ass if you get in my way.

But as soon as I turned into the driveway that led up to the farmhouse my grandfather had built over eighty years ago, I knew it was all wrong. I should have stuck with the jeans and the lime-green tank top.

I screeched to a halt and reached into the back seat where my rejected outfits were flung over my four suitcases, five boxes of books and records, and three giant plastic containers of photos, notebooks and dog food.

“This is the last change,” I muttered to Tripod, who just stared at me like I was a lunatic—which maybe I am. But who wants a dog passing judgment on you?

I glowered at him as I shimmied out of the spandex capris. They were getting kind of tight. Surely I wasn’t already gaining weight?

I was standing barefoot beside my open car door with my jeans almost zipped when my cranky three-legged mutt decided he’d had enough. Up to now I’d had to lift him into and out of the high seat of my ancient Jeep. That missing foreleg makes it hard for him to leap up and down. But apparently he’d been playing the sympathy card the whole two thousand miles of I-10 east because, as soon as I turned my back, he jumped down through the driver’s door and took off up the rutted shell driveway, baying like he was a Catahoula hound who’d just treed his first raccoon.

“Idiot dog,” I muttered as I snapped the fly of my jeans. The day I adopted him he’d just lost his leg in a fight with a Hummer on an up ramp to I-405 in Los Angeles. Not a genius among canines, and an urban mutt, to boot. The only wildlife he’d ever seen were the squirrels that raided the bird feeder I’d hung in the courtyard of my ex-boyfriend G.G.’s Palm Springs villa.

But here he was, lumbering down a rural Louisiana lane, for all intents and purposes pounding his hairy doggy chest and declaring this as his territory.

I paused and stared after him. Maybe he was on to something. Straightening up, I took a few experimental thumps on my own chest. “Watch out, world—especially you, Alice. Zoe Vidrine is back in town, and this time I’m not leaving with just a backpack and three changes of clothes. This time I’m not going until I get what’s rightfully mine.”

Then before I could change my mind about my clothes one more time, I slid into the driver’s seat, shoved Jenny into first gear, and tore down the Vidrine driveway, under the Vidrine Farm sign, and on to the Vidrine family homestead.

It was the same house. That’s what I told myself when I steered past a large curve of azaleas in full bloom. In a kind of fog I pressed the brake and eased to a stop at the front edge of the sunny lawn. It was the same house with the same deep porch and the same elaborate double chimney. My great-grandfather had been a mason before he turned to farming, and the chimney he’d built on his house would have fit on a New Orleans mansion.

I was in the right yard and this was the right house. But nothing else about it looked the same. Instead of peeling white paint interrupted with gashes of DayGlo-red peace signs and vivid green zodiac emblems spray painted in odd, impulsive places, the walls were a soft, serene yellow. The trim was a crisp white, and shiny, dark green shutters accented the windows on both floors. A pair of lush, trailing ferns flanked the wide front steps, moving languidly in the gentle spring breeze.

The day I’d finally fled my miserable childhood, there had been no steps at all, only a rickety pile of concrete blocks.

Now a white wicker porch swing hung on the left side of the porch, and three white, wooden rockers sat to the right.

It was the home of my childhood dreams, of all my desperate, adolescent yearnings. Nothing like the place I’d actually grown-up in.

I shuddered as my long-repressed anger and hurt boiled to the surface. How dare Alice try to gloss over the ugliness of our childhoods! How dare she slap paint down and throw a few plants into the ground and pretend everything was just fine and dandy in the Vidrine household!

Then again, my Goody Two-shoes sister had always looked the other way when things got ugly, pretending there was nothing wrong in our chaotic house, that we were a normal, happy family. Judging from the House Beautiful photo-op she’d created here, she hadn’t changed a bit.

If I’d had any remaining doubts about claiming my legal share of this…this “all-American dream house,” they evaporated in the heat of my rage. She might believe her own crap, but I sure didn’t.

I shoved the gearshift into Park and turned off the motor. That’s when I heard the barking—Tripod and some other yappy creature. From under the porch a little white streak burst through a bed of white impatiens and tore up the front steps, followed closely by my lumbering, brindle mutt. Up the steps Tripod started, then paused, his one forefoot on the top step, daring the little dog to try and escape him now.

Tripod hadn’t treed a raccoon. He’d porched a poodle. He’d made his intent to dominate known in the only way the other dog would understand. That’s what I had to do with Alice.

I jumped down from the Jeep and marched up the neatly edged gravel walkway, feeling my heels sink between the pebbles with every step. Damn, I should have changed shoes, too.

Just as I reached Tripod and the base of the steps, the front door opened. Only it wasn’t Alice. A lanky kid in a faded Rolling Stones T-shirt burst through the screen door. First he scooped up the fluff-ball of a dog. Then he crossed barefoot to the edge of the porch. “Hey,” he said. “You looking for my mom?”

His mom. So Alice had kids.

“Hush up, Tripod,” I muttered, catching hold of the dog’s collar. “Yeah. I am—if your mom is Alice Blalock.” Blalock was Alice’s father’s name. Since Mom hadn’t been sure who my father was, I’d remained a Vidrine, like her.

“Alice Blalock Collins. I’m her son, Daniel.” He gestured to Tripod. “What happened to his leg?”

“A big car. Where’s your mom?”

“She’s up at the church. Who are you?”

I planted one fist on my hip and shrugged my hair over my shoulder. “I’m your aunt Zoe.” I’m your bad-seed relative your mother probably never told you about. “I’m your mom’s baby sister. So. When will she be home?”

I could see I’d shocked the kid—my nephew, Daniel. While he went inside and called Alice, Tripod made a methodical circuit of the yard, marking every fence post, tree trunk and brick foundation pillar. He hadn’t done this at any of the rest stops we’d slept at or the Motel 6’s I’d snuck him into. But somehow he seemed to know we’d reached our destination and that this place belonged to him.

At least half of it did.

As for me, I sat down on the porch swing and tried to get my rampaging emotions under control. I was here. It wasn’t what I’d expected. Then again, I don’t know exactly what I did expect. Mom had been dead twenty years, and I’d been gone even longer. It made sense that Alice would have changed things. Of course her life would have gone on. Mine had. She wasn’t a nervous twenty-year-old anymore. Just like I wasn’t a scared seventeen-year-old.

But today, back here in this place, I felt like one all over again. And I didn’t like the feeling.

“Come here, Tripod,” I called. “Good boy.” I fondled his ragged ears until his crooked tail beat a happy tattoo. “Good boy. You showed that snooty little cotton ball who’s boss, didn’t you? Come on. Get up here with me.”

I hefted his fifty-five-pound bulk up onto the swing beside me, somehow reassured by his presence. We were a team, me and Tripod. A banged-up pair of survivors who weren’t taking anybody’s crap. Not anymore.

From my perch on the swing I peered through the window into the living room. I saw an upright piano and two wing chairs with doilies on the headrests. Beyond them I saw Daniel pacing back and forth in the dining room, talking on the phone. I stilled the swing and strained to hear his end of the conversation.

“…yeah, Zoe. And she’s definitely not dead.”

She’d thought I was dead?

“But if she’s my aunt, how come you never—”

He broke off, but I filled in the empty spaces. How come she’d never mentioned me to him? No wonder he’d looked shocked. The kid, if he’d even known of my existence, thought I was dead.

Now that made me mad. It was one thing for Alice to wonder if I was dead. After all, I hadn’t talked to her since right after Mom died. And if she didn’t follow the music industry and see my occasional photo in an appearance with one of my several rocker boyfriends through the years, she might be excused for speculating that I was dead. But to not even tell her son that she’d ever had a sister?

I snorted in disgust. Obviously nothing had really changed around here except for a fresh coat of paint. Underneath, our family was as ugly and rotten as ever. Alice might want to pretend I didn’t exist, and she definitely wouldn’t want me in her house.

Problem was, it wasn’t her house. It was our house.

One thing I was certain of: my mother wasn’t the type to have written a will. Too conventional for her. Too establishment. That meant, according to Louisiana laws, which I’d checked into just last week, since Alice and I were my mother’s only children, we were her only heirs. And we shared equally in her estate.

Daniel edged out through the front door and stared uneasily at me. I raised my eyebrows expectantly.

“She’ll be here in just a minute.”

I smiled and with my toe started the swing moving. I needed to go to the bathroom in the worst way. But I wasn’t going to put this kid on the spot by asking to use the bathroom. I had to keep in mind that he wasn’t a part of my issues with Alice and this place. I remembered what it was like to be caught in the middle of warring adults, and I didn’t want to put him in that position.

“How come you’re not in school?” I asked, trying to be conversational.

“I’m homeschooled.”

“Homeschooled?” Oh, my God. Hadn’t Alice learned anything from our experience with Mom? I managed a smile. “So. What grade are you in?”

“Tenth. Sort of. Eleventh grade for English and history. Ninth for math and science. It averages out to tenth.”

“Yeah. I see. You have any brothers or sisters?”

“No.” He shook his head. “Just me.”

I nodded. “So…You like the Stones?”

He looked down at the logo on his T-shirt, a classic Steel Wheels Tour-shirt from the early nineties. It was probably older than he was. “Yeah,” he said. “They’re like real cool for such old guys.”

Okay, Aunt Zoe, here’s your chance to impress your nephew, who’s obviously never even heard of you. “You know, I’ve met Mick Jagger a couple of times. Partied with him and the rest of the Stones.”

His eyes got big. “You have?”

“Uh-huh. Keith Richards, too.”

His eyebrows lowered over his bright blue eyes. Alice’s eyes. Mom’s eyes. “My mother says Keith Richards is depraved.”

“Depraved?” I would like to have argued the fact. Anything to contradict Alice. But what was the point? So I settled for a vague response. “You know, not everyone who lives a life different from our own is depraved.”

“I didn’t say they were.” He looked at me, this earnest kid of Alice’s, and I suddenly saw him as girls his age must see him. Tall, cute, maybe a little mysterious since he didn’t go to regular high school.

Or maybe weird and nerdy, an oddball since he didn’t go to regular high school.

Damn, but I’d hated my brief fling with the local high school.

No. What I’d hated was being the girl who lived in the hippie commune. The girl whose mother never wore a bra. The girl who didn’t have a clue who her father was. At least Alice had her father’s last name. But I was just a Vidrine, like my mother, and other kids were merciless about it. Love Child, they’d called me, and sung the Diana Ross song whenever I walked by.

Tripod put his head on my knee and whined. That’s when I realized I was trembling, vibrating the swing like a lawn-mower engine. Even my dog could tell I was wound just a little too tightly.

I looked away from Daniel, wondering when Alice would get here, then wondering how I was supposed to make this plan of mine work if just talking to this kid got me so upset.

“Did it hurt?” he asked. “You know, when the car hit your dog?”

A new subject, thank God. “I guess it did. The first time I ever laid eyes on Tripod he was flying off the front fender of this giant black Hummer.” Which Dirk, my ex-ex-boyfriend had been driving. “I stopped and so did this other car.” Dirk drove off and left me on the highway. “Anyway, we got him to a vet, who said his leg was shattered and did we want to put him to sleep or amputate.”

“Wow. You saved his life and adopted him?”

I shrugged. It sounded so altruistic the way he said it. The truth was, I’d charged the vet bill to Dirk’s credit card, then kept the dog to remind me how glad I was to be rid of that SOB. Never date drummers, I’d vowed after that six-year fiasco had ended.

But at least I had Tripod. We’d been together for almost four years now. I rubbed his left ear, the one that had a ragged edge from some incident that predated the Hummer. “He may be an ugly mutt, but he’s my ugly mutt.” And the only semitrustworthy male I’d ever known.

We both looked up when a Chevy van pulled into the driveway, swung past my Jeep and pulled around the side of the house toward the garage.

For someone who hadn’t seen her only sister in over twenty years, Alice sure took her sweet time. She came in through the back door. I caught a glimpse of her in the house—much slimmer than I remembered but still pleasantly plump. She paused at a mirror and fiddled with her hair. Even then it took her another full minute to join us on the porch. I guess she had to brace herself. After all, she obviously felt like I’d risen from the dead.

As kids she and I hadn’t exactly been close. You’d think we would have clung to each other in the midst of all the chaos thrown at us. Instead we’d become each other’s primary targets, both of us competing for the meager fragments of Mom’s love and attention.

Later, when I’d begged her to leave with me, I couldn’t believe she meant to stay. As furious at her as I was at our mother, I’d left without her, scared to death but determined to go.

I’d had my revenge two years later, though, when she called me about Mom being sick. I told her point-blank that I didn’t give a damn about Mom and what she needed. Four months later Alice had tracked me down again to say Mom had died, and what did I think we should do about a funeral?

Though now I know it was illogical, my response at the time had been utter rage: at Mom for dying and at Alice for crying to me about it. And maybe at myself for feeling anything at all for either of them.

“Don’t you get it?” I said to her in this cold, unfeeling voice. “I don’t care what you do with her or anything else in that hellhole of a house. I left Louisiana a long time ago, Alice. Get over it.”

And that had been that. Our last conversation.

But even though that had been twenty years ago I could feel the old animosity rise, like a fever that the antibiotic of time had only held at bay. We were still competing for Mom’s scraps. Only in this case it would be our inheritance.

“Hello, big sister,” I said with a wide, for-the-camera smile.

Alice’s wasn’t quite so eager. “Zoe. Well, hello.” She stood there, just staring at me as if she hadn’t believed Daniel, as if she wasn’t sure she even believed her own eyes. She glanced at Daniel, then away, clearing her throat. “I see you’ve met my son.”

With my left foot I set the swing into motion. “Yes. He seems like a great kid, though I could swear he’s never heard of his aunt Zoe.”

If it was possible her pinched expression grew even tighter. “Go inside, Daniel.”

When he didn’t jump right up, she turned a stern look on him. “I said go. Finish the history chapter—”

“I already did.”

“Then start the next one. And take off that awful T-shirt!”

He muttered something under his breath, but he did as she said. When he opened the door, however, the poodle slipped out. One yip and Tripod sprung off the swing, nearly knocking Alice over when she snatched her obnoxious pet up from the jaws of death.

“Make him stop!” she yelled at me while Tripod bayed at the fur ruff she held up over her head.

It would have made a hilarious photo, my ugly, three-legged hound up on his hind legs trying to reach her sweetly groomed little dog while she screamed bloody murder. A great album cover for a band like Devil Dogs.

Slowly I unfolded myself from the swing. “That’s enough, Tripod. Come on, now.” He could probably tell I didn’t really mean it. That’s why I had to haul him back by the collar while Alice put “Angel” back in the house.

Then still not sitting down, she said, “So what brings you back to Louisiana?”

I perched on the porch rail like I used to when I was a kid, before it was torn off in a drunken rage by one or another of Mom’s so-called boyfriends. “This is home, isn’t it? I’ve come home.”

She got this wary look on her face. “What do you mean? You’ve been gone over twenty years, and all of a sudden, out of the blue, you decide it’s time for a visit?”

“Something like that. Only this isn’t a visit, Alice. I’m back to stay.”

That’s when she sat down. I guess the shock made her knees weak. “You mean you’re moving back to Louisiana? But…you said you hated this place. You called it a hellhole.”

In my opinion it still was. But I only shrugged. “Things change. Not only am I moving back to good old Oracle…” I said, watching her wariness turn to horror. “I’m moving back here,” I added, sweeping my hand to include the house and its forty-plus acres. “In case you’ve forgotten, it is half mine.”

Just like her son, Alice’s first reaction to the little bomb I’d laid on her was to run inside and get on the phone. I suppose she was calling her hubby so he could hurry home and somehow make me leave. Like that would work. It might have been an angry impulse when I ditched Palm Springs and my sunbaked, half-baked existence there. But I’d had six long days of driving with only a nauseated dog and a string of country and western stations to keep me company. Lots of time to think. And now I was committed to my plan. I wanted my half of our inheritance, and I wasn’t leaving here without it. Keeping this farm was the only thing my mother ever did right. With my share I could start a new life, someplace where neither G. G. Givens nor my mother’s ghost could find me.

So Alice could call her husband and all his kin, too. But she wasn’t getting rid of me until I had my money.

I heard voices from inside the house. Daniel was yelling at his mother and she was yelling back. But I couldn’t see them through the window. Well, it was my house, too, wasn’t it? So I got up and walked inside.

“…it’s still a lie,” Daniel shouted down at his mother from halfway up the stairs. “A lie of omission. Just like you said I did when I told you I was going to New Orleans with Josh and his big brother but didn’t tell you we were going to the Voodoo Fest.”

“That’s different,” Alice retorted. “You knew if you asked me to go to that Voodoo thing that I would say no. That’s why you didn’t tell me, and that’s why it was still a lie.”

“And you thought I would approve of you pretending you didn’t have a sister?”

Good point, kid. I crossed my arms, waiting for Alice’s reply. But when Daniel’s eyes shot to me, she turned around, too. She was shaking. I could see it on her pale face. It should have made me happy, seeing my Goody Two-shoes sister caught in a lie. Instead it made me vaguely uncomfortable. I didn’t care if she felt bad. But some small part of me didn’t want to make her look bad in front of her son. I remembered how awful it used to feel when my mom pulled some monumental screwup, some embarrassing public incident that I couldn’t overlook even with my hands over my eyes and my thumbs in my ears.

“She thought I was dead,” I blurted out. “Okay? I’ve never been very good about keeping in touch, so…” I shoved my hands into the back pockets of my jeans and shrugged. “You might say we’ve never really been close. But now I’m back,” I added, switching my gaze to Alice. “So where should I put my stuff?”

When she just stared at me with big, round—scared—eyes, Daniel answered for her. “There’s plenty of room upstairs. Two guest rooms plus mine and a study.”

“Daniel—” Alice raised a hand to him, then let it fall in the face of his anger and hurt. His mother had lied to him. I guess that hadn’t happened before. Lucky boy.

“Fine,” I said into the tense standoff between them. “It won’t take me long to unpack. Then maybe you and I can have a nice long talk, Alice, and catch up on the past—” twenty-three “—few years.”

I was just lugging my second-to-last load up the front steps—why had I brought so many records and books?—when a third car turned into the yard. A burgundy Oldsmobile. An old man’s car, and given that the guy who got out had a full head of white hair it seemed like I’d guessed right.

I ignored him and let the screen door slam as I went inside. Once I got everything in my room, I planned on taking a bath. Then I was getting the hell out of this house for a while, because already it was giving me the creeps. It would take more than a few coats of Sunny Yellow and Apple Green latex to paint out the stains of my miserable childhood.

Outside I heard Tripod barking, then a man’s voice yelling, “Shoo. Get away!” Then, “Alice. Alice!”

Upstairs I looked at Daniel’s closed bedroom door. He’d been in there ever since his fight with his mother. Downstairs I heard Alice fussing at Tripod. I guess the man of the house got inside unscathed. I dug around for a dog biscuit before heading downstairs for the last box. Tripod deserved a reward for sticking up for me.

In the front parlor Alice sat hunched over on an elaborate settee, her husband next to her with an arm around her bowed shoulders. When he heard me on the stairs, he looked up and glowered at me. “Is this any way to treat your only sister?”

I planted one fist on my hip. “I’ve ignored her for twenty-three years and she’s done the same to me. How does that make me the villain and her the victim?” Then I strode forward and stuck out my hand. “Hi, I’m Zoe. And you must be…”

By now Alice had bucked up enough to speak for herself. “This is Carl Witter, a…a friend of mine.”

A friend? He looked a bit possessive of her to merely be a friend. And he ignored my hand. “Oh,” I said, pulling it back. “A friend. Where’s your husband?”

If possible, Carl’s pale eyes turned even colder. “Reverend Collins died thirteen months ago,” he bit out. “Which you would have known—”

“If she had told me,” I threw back at him. Alice had been married to a minister? I pushed that question aside. “I guess that makes you the new boyfriend.”

“I’m her friend,” he bit out. “And I’m not about to let you take advantage of her sweet nature, especially with an impressionable young man in the house.”

“An impressionable young man who didn’t know till now that he had an aunt.” The more I thought about that fact, the madder I got.

He leaped to his feet. “Given the aimless, Godless life you’ve led!”

“Stop it, Carl,” Alice begged, tugging on his arm.

“You don’t have to let her stay here,” he told her. “This is your home.”

“Which happens to be half mine,” I said.

That stopped him cold.

“Look,” I said before he could start up again. “Why don’t you and Alice go back to whatever you were doing. I can finish moving in without any help.” Then flashing them a smug smile, I flounced out of the house.

From behind a closed door—what used to be the “Meditation Room” when we were kids but what had actually been the “High Way Room” for getting loaded—I heard Angel yapping. From his spot on the porch, surveying his new domain, Tripod let out a warning bark.

“Good boy,” I told him, rubbing his ears the way he liked. “I think we’ve each won the first skirmish.” It was mighty interesting that, considering she thought I was dead, Alice and her creaky boyfriend sure seemed to know all about my “aimless, godless life.”

I straightened up and looked around me. The porch, the house, even the grounds looked nothing like how I remembered. But the ghosts of my childhood were still there, waiting to jump out at me. God, I hoped it didn’t take long for Alice to give me what was my due. I didn’t think I could last very long in this haunted house of ours.