Читать книгу Old Boyfriends - Rexanne Becnel - Страница 8

CHAPTER 1 Death and Dieting

ОглавлениеCat

M y friend M.J.’s husband died on a Friday, lying on the table during a therapeutic massage. A massive heart attack, that’s how the newspaper reported it. But that’s only because his son and the PR firm for their restaurant chain made sure that’s what they reported.

The truth? Viagra and the too-capable ministrations of a pseudowoman, pseudomasseuse wearing a black oriental wig, a red thong and fishnet hose are what did in Frank Hollander. The table was actually a round bed covered with black satin sheets, with an honest-to-God mirror on the ceiling. The House of the Rising Sun serves a very good hot and sour soup downstairs, but the therapy going on upstairs isn’t the sort that the chairman of this year’s United Way Fund Drive could afford to be associated with.

Needless to say, the funeral was huge. The mayor spoke, the bishop said the mass, and the choir from St. Joseph’s Special School, a major beneficiary of the United Way, sang good old Frank into the ground. As pure as those kids’ souls were, even they couldn’t have sung Frank into heaven.

Afterward, M.J.’s stepchildren entertained the mourners at her home, where everyone came up to the widow and said all the things they were supposed to:

“If I can do anything, Mary Jo, just call. Promise me you’ll call.”

“Your husband was a great man, Mrs. Hollander. We’ll all miss him.”

Blah, blah, blah. It was all I could do to keep my mouth shut. But Bitsey had given me my marching orders and I knew my role. I was there to support M.J., not to air my opinion about her sleazy bastard of a husband and his gang of no-good kids.

Thank God for Bitsey—and I’m not using the Lord’s name casually when I say that. Thank you, God, for giving me Bitsey. She’s like the voice of reason in my life, the perfect mother image for someone sorely deprived of that in her biological parent.

M.J., Bitsey and me. Three girls raised in the South, but trapped in California.

Well, I think that maybe I was the only one who felt trapped in the vast, arid beigeness of southern California. But then, I felt trapped wherever I was. I was slowly figuring that out.

That Tuesday, however, at M.J.’s palatial home with the air-conditioning running double time, and Frank Jr.’s Pacific Rim fusion restaurant catering the after-funeral festivities, we were all feeling trapped. Sushi at a funeral is beyond unreal.

Bitsey had explained to M.J. that she had to stay downstairs until the last guests left. She was the hostess, and it was only right. But yes, she could anesthetize herself if she wanted to. Everybody else was.

So M.J., in her perfect size-six black Giselle dress and her Jimmy Choo slingbacks, sat in Frank Sr.’s favorite fake leopard-skin chair and tossed back five vodka martinis in less than two hours.

M.J. drank, Bitsey ate, and I fumed and wanted to get the hell out of there. That awful, morbid couple of hours sums up pretty well how the three of us react to any stress thrown our way. And God knows there’s enough of it. When Bitsey hurts, she eats. Even when she was on Phen-Fen, and now Meridia, if she’s hurting—especially if her husband, Jack, pulls some stunt—she eats. Considering that Jack Albertson can be a coldhearted bastard, and unlike Frank, doesn’t bother to hide it, it’s no wonder she’s packed close to two hundred pounds onto her five-foot-four frame. The more she eats, the fatter she gets, and the more remote and critical he gets. Which, of course, makes her eat even more.

But I digress, which I do a lot. According to my sometimes therapist, that’s a typical coping mechanism: catalog everybody else’s flaws and you’ll be too busy to examine your own. M.J. drinks, Bitsey eats, and I run. New job. New man. New apartment.

Today, however, I had vowed to hang in there, bite my tongue and generally struggle against every impulse I had.

“So sorry, Mrs. Hollander.” A slick-looking man with a classic comb-over bent down a little to give M.J. his condolences. His eyes were on her boobs, which are original issue, contrary to what most people think. He handed her his card. “If I can help you in any way.”

After he wandered away, Bitsey took the card from M.J.’s vodka-numbed hand. “A lawyer,” Bitsey muttered, glaring at his retreating back. “How positively gauche to hand the bereaved widow a business card at her husband’s funeral. Is there even one person in this entire state who was taught a modicum of manners?”

“She’s going to need a lawyer,” I whispered over M.J.’s head, hoping the vodka had deadened her hearing. “Frank Jr. isn’t going to let her get away with one thin dime of his daddy’s money. Her clothes, yes. Her jewelry, maybe. In a weak moment he might even let her keep the Jag. But the house? The money?” I shook my head. “No way.”

“Shh,” Bitsey hissed. “Not now.”

M.J. turned her big, fogged-over blue eyes on Bitsey. “I need to use the little girls’ room.”

“Okay, honey.” Bitsey patted M.J.’s knee. “Do you need help?”

Somehow we guided M.J. through the crowd without it being too obvious that her feet weren’t moving. Good thing she’s only about a hundred pounds. The girl is as strong as an ox, thanks to Pilates three days a week, cross-training two days and ballet the other two. But she doesn’t weigh anything.

Instead of the powder room, we took M.J. to the master suite where we surprised Frank Jr.’s wife, Wendy, scoping out the place. The bimbo didn’t even have the grace to look embarrassed that we’d caught her in the act of mentally arranging her furniture in M.J.’s bedroom.

But when I spied the delicate ceramic bunny rabbit she held in her greedy, sharp-nailed clutches, I saw red. Bloodletting red. Bitsey had made that rabbit in the ceramics class where she, M.J. and I first met. She’d given it to M.J., and a cat figurine to me. I glared at Wendy until the bitch put the bunny down and flounced away.

Bitsey gave me a scandalized look. “Please tell me she wasn’t doing what I think she was doing.”

I rolled my eyes, hoping M.J. was too far gone to have noticed her stepdaughter-in-law’s avarice. But as M.J. kicked off her shoes and staggered to the “hers” bathroom she muttered, “Wendy wants my house. Frank Jr., too. She’s always saying how a big house like this needs kids in it.”

M.J. paused in the doorway and, holding on to the frame, looked over her shoulder at us. Tears spilled down her cheeks. She was gorgeous even when she was drunk, miserable and crying. If she wasn’t such a lamb, I’d hate her. “Like I didn’t try to have children,” she went on. “I always wanted children, and we tried everything. But…” She sniffled. “I just couldn’t get pregnant. She always lords that over me, you know. We’re the same age, but she’s got three kids and I don’t have any.” M.J. went into the bathroom and closed the door.

Bitsey looked at me. Her eyes brimmed with sorrow, but her mouth was pursed in outrage. “And now Wendy wants her house?” She fished the lawyer’s card out of her pocket.

I snatched the card and tore it in half, then tossed it in a garbage basket. “No. Not that lawyer. If he’s here at Frank’s funeral it’s because he’s a friend or business acquaintance. Some kind of way he’s connected to Frank Sr., and therefore Frank Jr. When M.J. gets a lawyer, we have to make sure it’s someone who doesn’t have any ties to the Hollander clan.”

“You’re right. You’re right,” Bitsey conceded. “You have a very suspicious mind, Cat. But sometimes that’s good.”

“A girl’s got to watch out for herself.”

Bitsey gave me a warm, soft hug. “And for her friends.”

M.J. went alone to the reading of the will. We found that out later. I would have canceled my appointments to be with her if she’d asked. Bitsey would have gone, too, not that she would have spoken up against a room half full of lawyers—all men—and the other half full of relatives—all bloodsuckers. But at least M.J. would have had one person on her side.

M.J. went alone, though, and when I called her that afternoon to see if she wanted to have dinner, all I got was the answering service. Even the housekeeper was gone. That’s when I knew something was wrong. Ever since the funeral, M.J. hadn’t left the house except for her exercise classes. I called Bitsey.

“Maybe she’s taking a nap,” she said. Bitsey is big on naps.

“Or drunk.”

“Or drunk,” Bitsey agreed. “We should go over there.”

“What about Jack? Isn’t it his dinnertime?” I tried to keep any hint of scorn out of my voice; I’m not sure I succeeded. The thing is, Jack Albertson is an overbearing jerk. Bitsey is the perfect wife, but nothing she does is ever good enough to suit him. She’s Julia Child and Heloise rolled into one: perfect meals served in a perfectly kept house. I helped her decorate it, but she keeps it up herself. Even their kids are perfect, good grades, no car wrecks or illegitimate babies—no thanks to Jack. But does he appreciate any of Bitsey’s good qualities? Not hardly. In his book she’s too fat, too permissive, a spendthrift and a brainless twit. Oh yeah, and did I mention? He thinks she’s too fat.

Sometimes I hate the jerk. But then, I’m beginning to think that maybe I hate all men.

“Jack’s working late tonight,” she said. “His division is entertaining a group of businessmen from South Korea and they’re pulling out all the stops to impress them.”

What I heard in her determined explanation was, “He’s nothing like Frank Hollander, so just turn off that suspicious little mind of yours.” For her sake I did.

“Okay, then,” I said. “I’ll meet you at M.J.’s in, say, twenty minutes. We’ll take her out to dinner.”

Twenty minutes later nobody answered the door, so we went around to the back. The gate was locked, but through the iron fence and tall border of variegated ginger and papyrus plants we could see M.J. lying on a chaise longue on the far side of the pool. She was asleep. At least, I hoped she was asleep.

When we were hoarse from trying to rouse her, I swore. “That’s it. I’m going over the fence.”

It would have been easier if I was twenty years younger or ten pounds lighter, or both. I had on high-heeled mules, ivory silk cigarette pants and a sleeveless black turtleneck. Very chic and severe, as befits an interior designer to the quasi rich and famous of Bakersfield, California. But it was lousy rock-climbing garb, and by the time I tumbled into a bed of pothos and aluminum plants, the whole outfit was ruined. “Hells bells. I think I broke something.”

“No you didn’t. Open the gate,” Bitsey demanded. So much for being motherly.

We hurried over to M.J.; for once Bitsey moved faster than me.

“Please, God,” Bitsey pleaded. “Don’t let her be dead.”

“Don’t say that. She’s not dead,” I muttered. “Dead drunk, but not dead.”

I was right, but barely. The last bit of margarita in the pitcher next to M.J. would definitely have finished her off. She was breathing but not responsive beyond a few indecipherable mutters.

“We should take her to the hospital,” Bitsey said as we wheeled her inside on the chaise longue.

“She’s just drunk. Look how big that pitcher is. She drank almost all of it.”

“What if she took something else?”

“Like what?”

“I don’t know. Sleeping pills. Painkillers. And look how sunburned she is. She must have been out there all afternoon.”

M.J. woke up when we turned a cold shower on her. “Stop. Stop!” She covered her face with her hands and curled on her side in the group-size shower stall.

“Mary Jo Hollander, what did you take today?” Bitsey exclaimed in her sternest I-am-the-mother-around-here voice.

“Tequila. Leave me alone.”

“What else?” I turned the cold up to full blast.

“Nothing!” She squealed in protest. “Nothing else.”

“No pills?” Bitsey demanded, her blond hair beginning to droop in the spray from the five-point water delivery system. “Mary Jo! No pills?”

“Nooo!”

Bitsey and I shared a look. As one we decided to believe her. So I turned off the water, Bitsey found some towels, and together we got M.J. dry and changed and into bed. This was beginning to be a bad habit. After that, completely done in, we threw ourselves onto the twin couches in the living room.

Bitsey kicked off her shoes. “She shouldn’t be living alone.”

“We both live alone.”

“I don’t live alone.”

I massaged my left ankle, which still hurt from my adventures with the iron fence. “Your kids are gone. Jack’s never around. Face it, Bitsey, you’re just as alone as me and M.J.” I knew I was being mean for no reason, but I was in a pissy mood.

“On the rag are you?” Bitsey was a sweetheart, but she wasn’t totally defenseless.

She was no match for me, though. “At least I’m not too old to still have a period.”

She glared at me. Bitsey was very sensitive about the impending death of her forties. She’d gone through the same tortures when she was thirty-nine and her first daughter went off to college. Forty was old! Four years later her middle girl went off without too much trauma. But the baby had left last August, she’d turned forty-eight the next month, and according to her gynecologist, she was officially in menopause. She hadn’t yet recovered from any of it.

I knew she’d be okay once she actually turned fifty. But we had another year and a half till then. Despite my nasty mood, I probably shouldn’t have made that last crack.

“At least I won’t die alone,” she finally said, but without any real venom in her voice.

I hugged a silk-tasseled pillow to my chest. “Sorry.”

She nodded. “Me, too.”

We sat in silence, surrounded by the self-conscious splendor of M.J.’s home. Pure California posh. By day it was bright and elegant: white everything—floors, walls, carpets, furniture; art in every shade of red; and the bright green of potted palms and ferns. By night the lighting turned everything amber, dark emerald and the color of blood. Dramatic.

You’d think as M.J.’s best friend I would have been consulted on the decor. But Frank Hollander used a big interior design firm from L.A. for everything: home, restaurants and his latest venture, a boutique hotel in San Diego. Despite my professional jealousy I could appreciate the house’s artistic merit. But it didn’t suit M.J. She’s a big softy at heart, so that slick, polished look didn’t come naturally to her. She had to work at it.

“I’ll stay with her tonight.”

“Good idea,” Bitsey said. She sighed. “She needs to get out of here.”

“You mean a vacation?”

She shrugged. “Something like that.”

“The trouble is, if she leaves—even for a week—Wendy and Frank Jr. would be in here with the locks changed. Possession is nine-tenths of the law and all that.”

Prophetic words. Hours later, after we forced two cups of strong coffee into her, M.J. spilled all. “He left me with nothing. Well, practically nothing,” she wailed, sitting cross-legged on the bed.

It was a garbled tale, interrupted by a bout of vomiting and lots of tears. By the time we had the gist of it, M.J.’s head was beginning to clear. “All those years,” she muttered. “Seventeen years of marriage and he betrays me, not only with that…that freak of nature woman-wannabe, but he lied about taking care of me. The kids inherited the corporation, and everything belongs to it—the restaurants, the hotel, even my house. And my car, too!”

“Wreck it,” Bitsey muttered.

I swiveled my head to stare at her. “Wreck it? You mean the car?” M.J.’s Jaguar sedan is the most gorgeous hunk of metal and leather you’ve ever seen.

Scowling, yet also looking like she wanted to cry, Bitsey nodded. “Wreck the car, wreck the house, wreck his reputation.”

M.J. sat up against the leather upholstered headboard of her Ponderosa-size bed. Vindictiveness in Bitsey was enough to sober anyone. “Wreck my car?”

“Wreck the house?” I said. “What do you mean?”

Bitsey got up, turned her back on us and stared out at the pool and the cunningly lit courtyard that surrounded it. “He deserves to be punished.”

“He’s dead,” I pointed out. “That’s pretty significant punishment, don’t you think?”

She shook her head. “It’s not like we have to lie about him. The truth will do just fine.” She turned around. “Maybe a little public humiliation will teach those horrible kids of his to mend their ways while they still can.”

Personally I didn’t think Frank Jr., Celeste and Roger would learn anything from a stunt like she was proposing except to hate their father’s second wife even more than they already did. But what the hay. “I’m in. Heck, I’ll spread the word to everyone I know about Frank and how he really died. I’ll even write a damned press release and send it to every media outlet in Southern California—if that’s what M.J. wants. But Bits, the Jag? I don’t think I have it in me to wreck the Jag.”

I was trying to lighten the mood, but it wasn’t working, at least not with Bitsey. She planted her fists on her hips. “I say burn down the house and drive the car into the pool. What have we got to lose?”

I swallowed hard. I had never seen Bitsey so furious. It wasn’t like the stomping around, cursing fury I was prone to. I might fly off the handle, but Bitsey was too much the genteel Southern lady for that. Instead she was cold and bitter, very scary for such a truly nice person. Struck dumb by her outrageous suggestion, M.J. and I could only follow her as she headed for the kitchen.

“We can plant evidence to implicate Frank Jr. as the arsonist,” she went on. She was serious.

“And you know how to do this?” I asked. “Don’t you watch CSI? You can’t hide something like that.”

“We wouldn’t be hiding it. That’s the beauty of it all. We’d just make Frank Jr. look guilty. Or better yet, Wendy. They deserve it. And after all, they’ll be the ones to collect the insurance. I’m sure she can think of a hundred ways to spend that much money.”

She turned on the steam attachment of M.J.’s elaborate espresso machine. M.J. and I shared a look. Bitsey might be an avenging arsonist, but she made a damned good espresso.

It was after midnight. I had no business drinking coffee, even decaf with lots of milk. But we were avoiding liquor for M.J.’s sake, so coffee it was. We sat in the breakfast nook of M.J.’s kitchen, one of the only cozy rooms in her house. M.J. was wrapped in a pink French terry robe, looking small and childlike with her face washed clean of makeup and her hair pulled back in a ponytail. Even miserable and hung over, the girl managed to still look good.

“Okay,” Bitsey said, setting two mugs of perfectly foamed café au lait before us. “Cinnamon or chocolate shavings?”

I’ve often thought Bitsey should open a coffeehouse. A chain of them. Bitsey’s Kitchen Table.

“Okay,” she repeated, once we were all settled. “Maybe burning Frank’s house down isn’t the best idea. But we should at least strip the place and sell off whatever we can. I can’t believe Frank left you penniless. Seventeen years of marriage and he does that to you? God, men are horrible.”

M.J. stared down at her coffee. “I signed a prenup, you know. But I thought, since we stayed married more than the ten years specified, that I would at least get something. Only it turns out he doesn’t own anything in his own name. It’s set up so that it all belongs to the company.”

“Everything?” I asked. “What about your jewelry? Or the art?” I gestured to a Steve Rucker painting above the sideboard.

“The jewelry’s mine,” M.J. allowed. “I’ll throw it into the ocean before I let Wendy get her greedy mitts on it.”

“Amen,” said Bitsey. She dumped two spoons of sugar into her cup. I reached for a packet of the blue stuff.

“Who bought the art?” I asked.

M.J.’s face screwed up in a frown. “I bought most of it.”

“How?”

“Credit card, of course.”

“Whose credit card?” Bitsey asked.

M.J. straightened in her chair. “It’s in my name. But Frank always paid the bills.”

“Doesn’t matter,” I said. “The art you bought is legally yours, not some corporation’s.”

“Or at least half yours,” Bitsey said. With eyes narrowed, she looked from M.J. to me and back. “Let’s take it. But first let’s eat.”

She took over the kitchen and made us mushroom omelets and fresh-squeezed orange juice. “I can’t believe you don’t have any grits,” she said as we sat down at the chrome-and-glass breakfast table.

“Even I keep instant grits in my pantry,” I threw in. Though I prefer the real thing, microwave grits are better than no grits.

“Frank likes oatmeal. Liked,” M.J. corrected herself. “Liked.”

“Another poor choice,” I said. “Any man who doesn’t like grits should be viewed with suspicion.”

“Did Bill like grits?” M.J. asked.

“Kiss off,” I threw right back at her. Bill was my second husband, now my second ex-husband.

“Jack loves grits,” Bitsey said. “You remember what grits stands for, don’t you?” she added. “Girls raised in the South. Grits.”

That was us all right. Girls raised in the sweet, green humidity of the deep South, and decades later trying our best to get by in the desert that was Southern California—even if that meant burglarizing our best friend’s house.

We worked through the night, stacking paintings, prints, statues and all the silver and china in the garage. By nine in the morning we had a moving van and a storage facility lined up. By noon everything was gone, and by one we were all zonked out at Bitsey’s house. Her husband, Jack, woke us when he came home around six.

“What’s going on around here?” he said from the door to the master bedroom. His voice carried down the hall to where M.J. and I shared the guest room. “What are you doing asleep, Bits? Why are M.J. and Cat here?” He must have seen the Jag. “And where’s my dinner?”

I sat up; M.J. looked at me. We both strained to hear more.

“Honey, I’m home,” I muttered. As I said, I don’t like Jack. I used to. I mean, on the surface he’s a pretty nice guy. Most guys are. But Bitsey was my friend, and more often than not, Jack made her unhappy. That’s all I needed to know.

Apparently he closed the door behind him, because although I could tell they were talking, I couldn’t make out what they said.

“I think it’s time for us to go.”

“Maybe so,” M.J. agreed.

“What’s wrong with the world?” I asked as we slid into yesterday’s clothes. “Bitsey’s husband is a jerk. Your husband was a jerk. Certainly my two ex-husbands are jerks.”

M.J. paused in the process of brushing her hair. “Are you still sleeping with Bill?”

In a weak moment, fueled by margaritas, I’d once revealed that my second ex and I occasionally get together. I didn’t say we slept together, but M.J. and Bitsey had drawn their own conclusions. Accurate conclusions, I might add. I searched for my sandals. “Every now and again.”

“Recently?”

I looked up at her. “Why do you want to know?”

It was her turn to look away. “Because he called me a few days ago.”

“He called you? Bill called you? But why?”

She didn’t answer, which was answer enough.

“You’re kidding. He hit on you, the bereaved widow? My best friend? And he’s trying to get you in the sack?”

“I hung up on him.” M.J. stared earnestly at me. “As soon as I realized what he was leading up to, I hung up. And you’re right. He is a jerk.”

I managed a smile, but my heart was racing. Not from jealousy, though, and certainly not from anger at M.J. Bill was a jerk; I’d always known that. We’d divorced once I realized that he’d never been faithful, not even for one month during the four years we were together. But this was even worse. M.J. was my friend. How could he set his sights on her?

And why did the fact that he was attracted to her leave me so panicked? Any man still breathing is attracted to M.J.

But that sort of logic didn’t matter to me.

M.J. put a hand on my arm. “I’m sorry, Cat. Are you okay?”

“I’m fine. Fine. And there’s no reason for you to apologize. It’s not your fault he’s a lowlife asshole.”

I raked my fingers through my hair. I thought I was beyond being hurt by the scumsucker, but my hands were shaking. “I wish I was a lesbian. Women are so far superior to men.”

“Yes,” M.J. agreed. “We are.” She gave me a hug, which I really needed. “But despite Frank and Bill, I have to believe there are still some good guys out there.”

I let out a rude snort. “Yeah, maybe. But they’re all prepubescent. The trouble with men is that they all suffer from testosterone poisoning. It shrinks their brains and swells their balls and they’re never the same again.”

M.J. laughed, but I was serious. “Come on, Cat,” she said. “Surely you’ve known one or two good guys.”

“No. I don’t think so.”

“Well, I have.”

“Yeah? Who?”

“My old high school boyfriend, for one.”

“If he was so great, why didn’t you just marry him?

“M.J. sighed. “I wanted to. But he went away to college on a football scholarship, and Mama had me on the beauty pageant circuit. That was when I really believed I could have a future in the movies. I guess he and I just sort of drifted apart. You know how it is at that age.”

I slipped on my shoes and let the subject drop. But her remembered high school passion reminded me of my own. He’d been a skinny Cajun boy and our favorite date had been to go fishing. At least we always took fishing gear when we set off in his flatboat. But we never did catch anything. We were too busy making out.

Despite my cynicism, I couldn’t help smiling at the memory. God, how I’d loved that boy.

“Anyway,” M.J. went on. “Not to change the subject, but I thought of something, or maybe I dreamed it. Anyway, we have to go back to the house.” She smiled like an impish kitten. “Frank kept mad money. I don’t know exactly where, but I remember last year when his grandson had a DUI and they wouldn’t take credit cards at the jail. He went upstairs and came down with a fistful of cash.”

“Is there a safe?”

“Yes, but it’s downstairs, and I already checked it.”

While Bitsey fed her demanding husband, M.J. and I took my car to her house. She’d padlocked the gate so we knew Frank Jr. hadn’t been in yet. But it was only a matter of time. Two hours and twenty minutes later we found a false bottom in the humidor in Frank’s study. It was a large, freestanding piece made of beautiful English oak.

Big humidor equals big hidden panel equals big, big payoff. Frank might have let M.J. collect art, but it was obvious that he collected money. Packets of twenties, fifties, hundreds and five-hundred-dollar bills. In his desk drawer we found three collections of the new state quarters and an odd bag of felt-wrapped coins. Old ones.

M.J.’s eyes lit up as she snatched the bag from the drawer. “These must be valuable or he wouldn’t have kept them.” Then she grabbed a few more of her clothes, filled a garbage bag with boxes of shoes, and we left.

“Aren’t you going to padlock the gate?

“Nope. And I didn’t lock the house, either. I’m outta here, and I’m never coming back.”

“Maybe someone will break in,” I said, “and burn it down. Wouldn’t Bitsey be pleased.”

“Me, too.” M.J. snapped her seat belt on.

I gave her a sidelong look. She meant it. Since Frank’s death, M.J. had spent over a week drunk and less than a day sober. But I could sense some sort of change in her, as if she’d turned a corner, from shock to sorrow to really pissed off. I steered my VW onto the boulevard that led to the gate house for the exclusive neighborhood.

“So. Are we heading back to Bitsey’s?” she asked.

“No. Not there. Tonight you can stay with me. Tomorrow we’ll figure out your next step.”

Bitsey came over around eleven the next day. I was working from home, mostly phone stuff, and I had a meeting at a client’s home at two. M.J. was in the shower. She’d already exercised for an hour and a half, made us a healthy breakfast of OJ, cracked-wheat toast, organic boysenberry jam and melon balls. Bitsey had a Krispy Kreme napkin in her hand and a sprinkle of sugar on the stomach of her olive-green jumper.

Bitsey flung her hobo bag onto the kitchen counter, stepped out of her shoes, then plopped down in my window seat. I looked at her over the rim of my red polka-dot Peepers. “Have you been crying? What did he do?”

She shot me a belligerent glare. “Why do you always assume it’s Jack? You never give him a chance.”

Tread lightly. “Well, since it’s only you and him at home now…” I raised my brows and trailed off.

“I talked to Margaret this morning.”

Margaret was the middle of Bitsey’s three perfect daughters, the one with the most potential for not being perfect. “Is she all right?”

“I don’t know.” Bitsey heaved a weary sigh. “You know she transferred to Arizona State. Well, it turns out she hates it there.”

“The state or the university?” I asked. “Or maybe the state and the university?”

She ignored me. “What if she drops out? Jack says if she does she can’t come home.”

I sat down next to her. “That’s not much of a threat anymore. At her age she probably won’t want to come home.”

Bitsey looked down at her lap and plucked at the Krispy Kreme sugar. She needed a manicure, I thought, then immediately hated myself for noticing. Sometimes I can be so shallow. The last thing Bitsey needed was her friends magnifying her insignificant flaws. Jack was more than up to that task.

She let out another deep sigh. “I wish I didn’t have to go home, either.”

Uh-oh. This didn’t sound good. For all the ups and downs in her marriage, the one thing Bitsey had never done was consider abandoning it. At least not out loud. I might not like Jack Albertson all that much, but I’d been divorced twice and I knew just how hard the process could be. I wasn’t so sure Bitsey was up to it.

“What’s wrong, Bits?”

She was blinking hard. “What if…” She swallowed hard, then turned to look at me. “What if Jack’s having an affair? If Frank could cheat on M.J.—you know how beautiful she is and he was just this wrinkled old man—if he could cheat on her, then what do you suppose Jack is doing to me?”

“Oh, Bitsey, I’m sure he isn’t doing anything of the sort,” I lied. For friends like Bitsey, you lie even if it tastes like gall.

She stared me straight in the eye. “You’re lying. I know you don’t like Jack. He’s critical and demanding, and he takes me for granted. You’ve pointed that out a hundred times.”

“That doesn’t mean he’s cheating.”

She pressed her lips together and blinked several times. “Maybe. Maybe not.”

M.J. came into the kitchen, her hair in a towel. “I don’t think Jack’s the type to cheat,” she said. Obviously she’d overheard our conversation.

Bitsey heaved that same, desolate sigh. “Did you think Frank was the type?”

M.J. shoved her hands deep into the robe’s pockets and shrugged. “I tried to pretend he wasn’t, but I knew he was. After all, he was married when we met.”

M.J. had been a trophy wife. Before that she’d been a twenty-three-year-old beauty pageant winner and aspiring actress, working as a hostess in Frank Hollander’s restaurant. He had kids almost her age, and when he’d dumped wife number one for her it must have been as bad as any cliché out there: a middle-aged man and his sex kitten.

Of course, I can understand why he’d fallen for her, and it’s not just how she looks. M.J. is one of those good-hearted, loving women who always tries to please the people she loves. And she’d really loved Frank.

There’d been no pleasing Frank’s kids, though. Some would say she’s getting what she deserves now, and I admit I even thought it. But not for long. To know M.J. is to love her. And I do love her.

“I used to be thin,” Bitsey said. “When Jack and I met I wore a size eight. Then I had all those kids.”

“I wish I had kids,” M.J. said in a quiet voice. “Tight buns and great abs are no substitute for a real family.”

“What about me?” I put in. “I don’t have kids or tight buns. By rights y’all should be feeling sorry for me.”

Neither of them laughed. Bitsey made coffee and we went out into the courtyard.

“That’s new,” Bitsey said of the plant nestled beside the pond.

“Louisiana Blue Iris,” I said.

That made M.J. smile. “There used to be drifts of those back home in the marshy area behind our house. Where’d you get it?”

“That specialty florist on San Pedro Avenue.” I stroked the deep purplish-blue flower. “A little taste of home, but without all the aggravating people.”

We were silent for a minute, then Bitsey looked at M.J. “Have you considered going home for a while?”

M.J. frowned. “Home? You mean like to Louisiana?”

“Don’t talk like that around me,” I said. “It gives me hives and I’ve got a very important meeting this afternoon.”

Bitsey didn’t spare me a glance. “Now that you’re out of that house and have a little money, you could go home to see your mother.”

“She moved to Florida,” M.J. said. “But maybe…”

“Does that mean you don’t have anybody left in New Orleans?”

“Not really. I mean, I have an aunt and two cousins. But I think maybe they’ve moved, too. The cousins, I mean.”

Bitsey stared into her half-empty coffee mug. “My dad’s still there, and it’s been three years. I guess I ought to go visit him. And I was planning to go,” she added. “But now…”

“Now what?” I asked when M.J. didn’t. You have to understand that Bitsey isn’t the sort to come right out and reveal her feelings. Maybe if she’s angry, but not if she’s sad. Right now she was seriously down in the dumps.

M.J. reached out and squeezed Bitsey’s hand. “Hey, Bits, what’s going on?”

Bitsey shook her head and put on her “it’s nothing” smile. “I got this invitation. That’s all. I was halfway thinking of going…”

“What, to a wedding?” M.J. asked.

“To my high school reunion,” Bitsey admitted. “My thirtieth.”

“Oh, you should go,” M.J. said. “I went to my twentieth and it was so much fun.”

Bitsey slowly shook her head. “I don’t know. Reunions can be hard and Jack can’t get away.” She sent me a quick, guilty look.

To my credit I kept my mouth shut and didn’t roll my eyes. But there was no way I would be able to restrain myself for long, so I changed the subject. “You never finished telling me what Margaret had to say.”

Bitsey gave me a grateful look.

“That’s right,” she began. “Well, like I said, Margaret’s not happy in Tempe. Five years, three majors, and now she’s thinking of taking a year off from school.”

“Maybe that’s not such a bad thing,” I said. “Maybe she needs more time to figure out what she really wants to do. “

“Tell that to Jack,” Bitsey muttered. Then she shook her head. “The thing is, there’s something else going on. I can feel it. I don’t know what it is exactly, but she’s so unsettled. So unfocused. Something’s wrong. I can hear it in her voice. But she won’t say what.”

Kids and how to deal with them were the one thing M.J. and I had no experience with—unless you count our mutual hatred of Frank’s awful kids. Generally we tried to be sympathetic with Bitsey’s situation, but we’d learned long ago not to be too forceful with our opinions. I could rag on Jack, but when it came to her kids, Bitsey was very sensitive.

A cloud passed over us, blocking the sun. It was such a rare occurrence that we all paused and looked up at the sky.

“What I wouldn’t give for a real thunderstorm,” I said. “Remember when you were a kid in the summertime and there was a storm, seems like every afternoon?”

“That’s the only time Mama used to let us play in the attic, when it was raining and we couldn’t go outside,” Bitsey said.

“We used to play under the house.” I said. Actually, it was a trailer up on cinder blocks, but they didn’t need to know that. Bitsey was a product of a Catholic elementary school and one of the best private high schools in New Orleans. M.J. was a suburban beauty queen. But I’d grown up in one of those spontaneous trailer parks that used to sprout up along the river road above New Orleans. To look at the three of us, we seemed pretty much the same. But we were a blue blood, a nouveau riche, and a redneck. And though we all visited our families now and again, we’d never all been back in New Orleans at the same time—which was just fine with me.

M.J. put her legs up on a wicker footstool. “You know, Bits, you ought to go to your reunion anyway. You could go with one of your old girlfriends.”

“Oh, I couldn’t do that.”

“Yes, you could,” I said. “Why should you have to miss your reunion because of Jack?”

“I’m not missing it because of him,” she said in this defensive voice. “He told me I could go.”

“Big of him,” I muttered.

“Be nice,” M.J. said.

“Look, Cat. The reason I don’t want to go…it’s because of my weight. Okay? Are you happy now? I’m fat and I don’t want my old boyfriend and all my cheerleader pals to see me like this.”

Why am I so stupid? As long as I’ve known Bitsey, you’d think I could have figured that out myself. Trying to backpedal I said, “Come on. You don’t think anybody else has gained a few pounds?”

She shook her head and looked away. “It’s a rule. Only thin people or the really successful, filthy rich ones go to their reunions.”

“Actually,” M.J. said, “I’d been thinking you looked a little thinner lately, especially around your face.”

For the first time since she’d arrived, Bitsey smiled. “Really? I’ve been dieting,” she admitted. “I told myself that if I lost twenty pounds I’d go to the reunion.”

“Good idea. So, how many have you lost?”

“Nine.” Her smile faded. “In two months only nine pounds. Even with the Meridia I didn’t make a dent.”

“But nine pounds is a good start,” M.J. said. “Really, it is. When is this reunion anyway?”

“Three weeks.”

The wheels were spinning; I could see it in M.J.’s eyes. “What if you and I took a little trip down south together?” she began. “I could get out of here—I don’t mean your apartment, Cat. I mean this town. Southern California. The desert.” She leaned forward to grab Bitsey’s arm. “I could use a change of scenery, and you could go to your reunion—”

“But I don’t want to go—”

“And in between, I’ll be your personal trainer.”

Bitsey started laughing. “My personal trainer? You mean, like, exercise? I don’t think so.”

“Come on, Bitsey. I need to practice on someone. Think about it. I have to either get a job or get a husband. And since I’m not ready for marriage—I don’t even have a boyfriend—it’ll have to be a job. But what kind of job am I eligible for? I suppose I could teach ceramics, but somehow I don’t think that would even pay for my manicures. But I could be a personal trainer. I could.”

She was right. I leaned forward. “You know, that’s a good idea. You’re already an expert in all sorts of exercises, and God knows you’re a walking advertisement.”

“Please, Bits, let’s do this,” M.J. said. “Let me practice on you and get you gorgeous. We could have a really good time down in New Orleans. By the time I’m through with you, you’ll make all your old girlfriends jealous and wow that old boyfriend of yours.”

“Hey? What about me?” I asked. Despite my aversion to them ever meeting any of my seedy family, I was beginning to feel left out. Besides, without them here to keep me sane, I might murder Bill. Accidentally, of course. “I could use a little making-over myself, and I could definitely stand to run into one of my old boyfriends, so long as he’s single and rich and not allergic to commitment.”

“That would be even better!” M.J. exclaimed. “All three of us together.” She caught my hand in hers, then took Bitsey’s in her other. “Let’s do it. We all have reasons to visit, so why not go together? We can make it a road trip, and along the way we’ll all get gorgeous. We’ll look up our old boyfriends, and we’ll have a terrific time. Come on, Bits, what do you say?”

Bitsey wanted to do it; I could see it in her sweet, yearning expression. But she was afraid. Well, damn it, so was I. Bad enough to go back there and deal with my mother and her other lousy kids, but last night after my conversation with M.J., I’d dreamed about making out in a flat aluminum boat with a lanky Cajun boy. Sure as anything, I was setting myself up for disappointment.

But it didn’t matter, because suddenly I wanted this trip in the worst way. “I’m in. I’m going with M.J. to Louisiana.” I grabbed Bitsey’s other hand and stared challengingly at her. “It’s on you, Barbara Jean. Are you in or are you out?”

Bitsey

I have been on and off diets for the past twenty-two years.

I diet before every single holiday, before we go on vacation, before every major social event, and afterward, too. My closet is organized with size eights in the back, then tens, and so on and so forth. I wore the eights and tens during the eighties when Jack and I first came to California. During the nineties I graduated to twelves and fourteens. The millennium ushered in the sixteens. Now I’m in eighteens, but I’ve taken a stand. I refuse to go into size twenty. It’s getting mighty tight, though.

When the invitation came from my high school reunion committee, it seemed like an ideal way to motivate myself. I made an appointment with my doctor, started taking Meridia, and vowed that this time I would succeed. And at first I did. I lost nine pounds the first month. That’s pretty good. But since then I’ve lost nothing. I’m stalled. Nine pounds is not enough to return to New Orleans. Nine pounds is not enough to face Eddie.

Eddie, Eddie, Eddie. What is wrong with me? I wouldn’t be behaving like an insecure fifteen-year-old if a different name had been listed on the reunion committee. But there it had been: Edward Dusson, Cochair. Eddie Dusson. Harley Ed, I used to call him. Dangerous Dusson, the other cheerleaders had said. My heart hurts just to remember how much I loved him in high school, and how much he’d loved me. But if I walked up to him today, would he even recognize me?

Then again, who’s to say that he hasn’t gained a hundred pounds himself?

I can’t imagine that, though. Not Eddie. Besides, if he’s on the reunion committee, he must still be fit and trim, still good-looking, and probably rich by now, too.

If only I could go see him and yet not have him see me. It was almost a relief when Jack said he couldn’t get away from work. I didn’t have to decide; he’d done it for me. I could be angry with Jack and hide at home, and on the weekend of the reunion, I could sit two thousand miles away and pig out on Oreo and Jamoca Almond Fudge.

But I have more pressing problems than Eddie’s weight and his bank account. This morning I telephoned Margaret, and her roommate informed me that Margaret had moved out. I must have sounded like an utter fool, a mother too stupid to know what her own child was up to. “Yes. Two weeks ago,” her roommate had said in this “you poor, pathetic thing” voice. The snooty little brat.

It turns out my middle child, the one with the highest IQ but the lowest level of ambition, is living with some guy she’s never even mentioned to me.

I knew something was wrong. I knew it. I should never have let her live off campus. I should have made her stay at an in-state university. I should have realized that even at twenty-two she wasn’t responsible enough for college. Junior college maybe, but not a big liberal arts school.

I called her on her cell phone, and after three tries reached her. She was in a bad mood already, because I’d awakened her. She is so much like her father, a total grump until he’s had his coffee. But it was ten o’clock in the morning. On a weekday most people are up by then.

Except that cocktail waitresses aren’t like most people. A cocktail waitress! It turns out that she works a late shift from six until two in the morning, and sometimes even later. But she makes great tips, she told me, so she thinks it’s worth it.

Oh, and his name is Gray. “He’s a bass player, Mom, in a roots rock band.”

A roots rock band. What is that supposed to mean? And what kind of musical roots does Tempe, Arizona, have anyway?

I shouldn’t have gone to Cat’s house after that call. I should have just crawled back into my bed. After all, Jack wouldn’t be home until after eight. All I had to do was order dinner from Gourmet Wheels, put it into my own pans, and he’d never know the difference.

But I couldn’t make myself sleep during the day without taking a Xanax, and I didn’t want to do that. So I threw on a green linen jumper over a white T-shirt, stuck my feet in my favorite espadrilles, and ran to Cat and M.J.

“It’s on you, Barbara Jean,” said Cat in that schoolyard bully way she sometimes gets. “Are you in or are you out?”

If they each hadn’t been holding one of my hands, I would have said “Out.” I would have. Except that when Cat and M.J. gang up on you, there’s really no way to defeat them, at least no way for me to defeat them. But it’s not because I’m a wimp. It’s because they make me brave. They grab hold of my hands, and all of a sudden Cat’s loud bravado and M.J.’s determined optimism spread through me like the enticing aroma of fresh-baked cinnamon rolls on a Sunday morning when the girls were little and all lived at home.

“I’m…in,” I said, hoping I wouldn’t regret it.

“Yes!” M.J. cried. “Here, let’s have a toast.”

We lifted our coffee mugs and clinked them together. “To road trips,” Cat toasted.

“To losing weight,” I added. “And fast.”

“To friends,” M.J. said. “And maybe old boyfriends, too.”

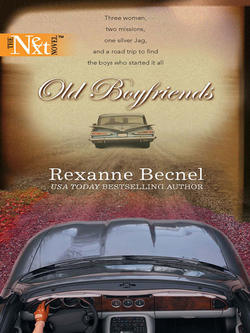

The rest of the morning passed in a blur. We had plans to make, a diet and exercise regimen and a travel itinerary to arrange. Cat would have to take time off from work. We decided to drive M.J.’s Jaguar. Cat was ecstatic about that. She hates to fly, and we would need a car when we got there anyway. So we’d make it into a real road trip, and if I wanted, we could stop to see Margaret in Arizona.

I calculated that if I restricted my caloric intake to below a thousand a day I could lose eight pounds in the next three weeks. Maybe even ten.

But only a thousand calories? I’d already eaten that much for breakfast.

That night I told Jack about our plans. I had returned home midafternoon, and in a frenzied burst—of guilt, I guess—I cooked his favorite Fiesta shrimp pasta for dinner. I also prepared a pot of gumbo—his mother’s recipe, not mine—and a pork roast stuffed with garlic. Tomorrow I planned to make a pan of spinach lasagna as well as a pot of Chicken à la Bushnell. That way I could freeze more than a dozen meals for him to eat while I was gone. All he would have to do was supplement them with salads and a hot roll or two.

“Why are you driving there?” he asked. “That’s a four-or five-day trip, assuming nothing goes wrong.”

“What can go wrong? As long as we stay on I-10 heading east we can’t get lost.”

He made a sarcastic sound. “The way you three jabber, you’ll miss a turn and end up in Idaho before you notice.”

“We will not!”

He got up from the table and without responding, headed for the television in the den.

I hate when he ignores me like that. It’s like getting in the final word, without saying anything. I wanted to scream, but of course, I didn’t.

After I loaded the dishwasher, I followed him into the den. He was reading the latest issue of U.S. News & World Report with the television on.

“I’ll leave the freezer stocked so you won’t have to worry about meals.”

“That’s all right,” he said, without looking up. “I can always order out. Just leave the phone number of that place you use.”

“The place I use?” I stared stupidly at him. “What place?”

“I don’t know the name. Meals on Wheels. Something like that.”

My heart did this great big, guilty flip-flop in my chest. He knew I sometimes used Gourmet Wheels? I was ready to abandon the trip right there. The one value I still had to Jack was my cooking ability. But if he knew about Gourmet Wheels and they were good enough for him, what did he really need me for?

He tossed the magazine on a side table and glanced at me. “So, when do you leave?”

“Um…next Friday,” I mumbled. “I’ll call you every night.”

“Okay.” He reached for the remote control and flipped through the channels. “You’d better tell the girls. Oh, look. They’re rerunning that Jackie Gleason biography, the one with the guy from Raymond.”

I went into the bedroom, closed the door and burst into tears. Then I called Cat and M.J.

We stayed on the telephone for two hours. You’d think we were teenagers the way we talk. Cat can make anyone laugh, she just has that way about her. She’s sarcastic and totally irreverent. She could be a stand-up comic if she wanted to, which always makes me wonder about her upbringing. I read Roseanne Barr’s biography, and Louie Anderson’s, and I know that the best comedians usually come from awful childhoods. The fact that Cat hardly ever mentions her family actually reveals a lot about her. But all she’s ever told us is that she grew up in one of those small towns strung up and down both sides of the Mississippi. For the most part they’re just clusters of little frame houses and the occasional trailer park, the kind that always attract tornadoes. My guess is that her father worked in one of the chemical plants.

As for me, I, too, sprang from that part of the state, only my grandfather owned six hundred acres of land there, an old sugar plantation that had been in the family since the early nineteenth century. He sold it right after World War II to one of those same chemical companies, and he made a lot more money from the sale than he ever did raising sugar.

Thanks to Pepere, my family has lived well ever since. He bought a huge Greek Revival house in the richest New Orleans neighborhood he could find, the Garden District, then proceeded to join every private club and exclusive society he could. He lived like a king for ten more years until he walked in front of a streetcar. He lingered three weeks, then died.

A month later my father eloped with my mother, a woman his father hadn’t approved of, and moved her into his father’s house. He lives there still, but alone now. Memere died when I was six. Mama died eight years ago. But at seventy-seven Daddy is going strong. He’ll be overjoyed to have all of us stay with him.

Cat and M.J. were pretty pleased by the idea, too. I just hope they don’t become awestruck when they see the way I grew up. The problem is, our house is huge. Magnificent even. It’s been written up and photographed for innumerable publications, as much for its architectural value as for the antiques that fill every nook and cranny. Mother bought only the best. Her entire life was dedicated to proving that she was good enough for the La Farges. Even though Grandmother was never as unkind to her as Grandfather had been, I don’t think Mother ever felt good enough for either of them, let alone the rest of her in-laws. So she did everything she could to make herself seem good enough to belong in their family.

Mother took classes in all sorts of subjects: art, music, antiques, and she was on so many committees and foundations I don’t know how she kept up. Our house was used for every kind of society fete you could imagine. But she only picked the charities that made her look like a generous benefactress or patron. Forget political fund-raisers. She was terrified of offending someone by taking a position on anything that might be controversial. But crippled children or multiple sclerosis or art education, the museum or symphony or ballet association—those were her charities.

To be fair, she did a lot of good. She was even nominated for the Times-Picayune’s Loving Cup. But she didn’t do it out of love. She did it to look good.

I always knew I was a disappointment to Mama. I hated all that society posturing, and I didn’t want to join a sorority at LSU. But of course I did. She planned my wedding to meet her standards, then helped us pick out an appropriately grand house to live in. But she was always on me about my clothes, my friends and especially my weight. It was a relief when Jack was transferred to California and I no longer had to see her every day.

Fortunately my brother married a woman even better connected in New Orleans society than he was. They were married just before Jack and I moved, and she and Mother became inseparable. I was sick with jealousy for years. Six years, twice a month with Dr. Herzog, to be exact. Then Mama died and so did my jealousy, though I still see Dr. Herzog now and again for other reasons. Anyway, my brother and his wife live in a monstrous Palladian-style mansion on St. Charles Avenue, so Daddy’s house is practically empty. We girls would have the entire second floor to ourselves.

Cat yawned into her end of the phone. “Some of us have to work tomorrow. Y’all can talk all night if you want, but I’m turning in.”

“’Night, Cat,” I said.

“’Night, Cat,” echoed M.J.

After the click M.J. started laughing. “You should see her face. She can’t stand to miss anything, so you know she must be tired.”

“So am I,” I said. “Tired and excited and scared.”

“Me, too,” M.J. said.

“Are you going to stay there? In New Orleans, I mean?”

She was quiet. All I heard was the faint rhythm of her breathing. “I don’t know. I don’t think so. But maybe. Except that I need you and Cat. What would I do without y’all? So no. I don’t think I can stay.”

All it would take was the right man to keep her there. I knew it but didn’t say so. The odd thing was, M.J. was even more scared than I was to go home. And I think maybe Cat was, too. It was a novel concept. What is it about home and the family and friends we leave behind? Compared to them we were all failures—failed marriages, failed careers. Well, Cat was doing okay in that department. But she’s the one with two divorces.

On the other hand, I told myself, marriages unravel in New Orleans, too. Youthful plans fall apart. Children disappoint you. You disappoint you. Maybe the secret to high school reunions was lying, creating another wonderful life that makes everyone else’s feel inadequate. I could do that, couldn’t I?

“Well, good night,” M.J. said. “See you at nine. And wear comfortable clothes and tennis shoes.”

“Okay,” I said. “Good night.” Comfortable clothes? Tennis shoes? I hung up the telephone and went to my closet. Big loose dresses. Too-tight pants. I closed the door and turned away, then reached for the Xanax. Tomorrow was going to be rough. I needed a really good night’s sleep to get through it.

I woke up late. Jack had already left for work. I saw his cereal bowl in the sink and his orange juice glass. I hadn’t made him breakfast on a weekday since Elizabeth left for college. She’s our youngest. Cat was gone, too, when I arrived at her house. The whole world was at work except for me and M.J., and she was doing warm-up stretches. I slunk into Cat’s sunroom feeling guilty, but M.J. didn’t fuss about the time.

An hour later I was close to tears. “No. I cannot do even one more.” Crunches, lunges, pliés, punches. I couldn’t do anything that involved any moving at all. I lay on my back on the floor and wiped the sweat from my brow. “I think I broke something, M.J. I’m not joking.”

She ignored me and like a sadistic drill sergeant, fixed me with an unsympathetic gaze. “You didn’t break anything, Bitsey. But you did use muscles you haven’t used in years.”

Somehow I rolled over and pushed up onto my knees. “And I don’t want to ever use them again.”

“Once we cool down you won’t feel so bad. Just remember your goal, to make that old boyfriend of yours sick over what he missed out on.”

Of course, that was the precise moment I caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror over the gold-leafed, side table against the far wall. A red-faced, middle-aged woman with ugly hair and wet spots everywhere her too-tight T-shirt snugged up to the rolls in her belly and arms. I squeezed my eyes closed against the sight, and against the tears. “This is not going to work, not in three weeks. Not in three years.”

“Oh, yes, it will.” She steered me toward the powder room. “Wash your face, comb your hair, then grab your sunglasses and visor. We’re going for a walk.”

That day I drank ten glasses of water with lemon, and three glasses of juice. Orange juice, cranberry juice and white grape juice. I had a salad for lunch, grilled vegetables and salmon for dinner and an apple for my evening snack.

“No cheating,” was the last thing M.J. said as I crawled into my Volvo. “I’ll be over in the morning to clean out your pantry and your closet,” she said, looking as fresh and perky as a prep school cheerleader.

“I hate you,” I muttered, glaring at her in the rearview mirror as I pulled out of the driveway. “I hate you and I hope you gain a hundred pounds. And that your boobs sag down to your waist.” She wouldn’t be so perky then.

I was in bed when Jack got home, and in bed when Cat called. I didn’t answer the phone but she knew I was there.

“I heard what she did to you,” Cat said into the answering machine. “And you have my condolences. Call me if you need anything. I have some prescription-strength Advil and three heating pads. Good night, Bitsey. I love you.”

The next day M.J. and I walked again, though walking is a relative term. She strode, I staggered. I suppose that averages out to walking. Afterward I watched while she emptied my pantry of every gram of carbohydrates. “Nothing white stays,” she said, “except on your hips and thighs.”

“But you drink,” I protested. “Like a fish,” I added, and none too nicely. But since drinking was her only vice, I meant to milk it for all it was worth.

She sent me a cool look. “The difference is that I exercise enough to counteract the calories. You’ll be able to drink, too, once you lose the weight.”

“So since I never want to drink as much as you do, does that mean I won’t have to exercise as much?” My voice was sweet, but I was seriously annoyed.

She gave me a long, even look that made me feel like an evil stepmother. If I didn’t want to accept her help, fine. I didn’t have to make ugly little digs at her. But before I could attempt to redeem myself, she shrugged one shoulder. “You can do what you like, Bitsey. Meanwhile this stuff can all go to the food bank. Now, let’s tackle your closet.”

Cat came over after work. She stared at the mountain of clothes on my bed. It’s a big bed, a California king, and the clothes M.J. said I could no longer keep smothered it. Cat picked up an ivory silk shell.

“She says I can’t wear it,” I explained. “Even if I lose weight.”

“When you lose weight,” M.J. corrected me. “The problem is, the blouse isn’t your shade of white.”

“That’s because it’s not white. It’s ivory.”

“And it’s too yellow for your complexion. Just like your hair,” M.J. said.

I stared at her. First my pantry, then my closet. Now my hair?

Cat took a seat across the room, grinning like a redneck in a ringside seat at a Dixie wrestling match. Round one might have gone to M.J. But I wasn’t down yet. “I’ve always been a blonde and I’m not changing now,” I said, feeling more than a little rebellious.

“I’ve made an appointment for you with my hairdresser. Tomorrow at eleven,” M.J. went on as if nothing I said mattered. “By the way, have you weighed in today?”

I wanted to strangle her. She was as bad as Jack, always honing in on my weakest spot and winning the argument, of course.

To put it mildly, I had a terrible week. My whole body hurt, my pantry and closet were embarrassingly naked, and I decided I hated cottage cheese.

My daughters were no solace. Margaret never returned my calls, Elizabeth couldn’t talk because she had a big test and a big paper and a social calendar that left no room for her poor old mother. Jennifer talked, but I made the mistake of telling her I was on a diet, and after that all she could do was lecture me with her theories of what worked for her. Seeing as how she’s never been more than one hundred and ten pounds, her theories didn’t exactly carry much weight with me. No pun intended.

The only good thing that happened started off as a bad thing. M.J.’s hairdresser, Darius, cut all my hair off. And I do mean all. He had to get rid of the old perm, he said, and as much of the old color as possible. He left me a measly inch and a half. Then he dyed it an ashy blonde. I cried all the way to Nordstrom where, to make me feel better, M.J. bought me a pale aqua sweater and a pair of silver clip-on earrings shaped like shells.

Only after she left my house did I venture into the bathroom and stare at my strange reflection. Jack was going to have a fit.

Or maybe not.

What if he didn’t care? Or worse, what if he didn’t even notice?

I fiddled with the hair. Smart and sassy was what Darius had said. Hair with attitude.

Actually, I looked like Meg Ryan’s mother. Well, maybe her fat older sister. One thing I did notice was that the short hair made my eyes look bigger. And the aqua sweater gave them a sparkle. I decided to reapply my mascara and eyeliner.

When Jack got home I had dinner ready “You cut your hair,” he said as we sat down to eat.

I ruffled my hand through the short, thick tufts. “Yes, though the hairdresser went a little overboard. Edward Scissorhands. But I like the color.”

He grunted. He probably didn’t know who or what Edward Scissorhands was. He’s not a movie person, even after fifteen years in California. He glanced at me again. “I forgot how much you look like Margaret. Or the other way around.”

That was the best part of the day. Of the week. He thought I looked like Margaret, who is probably the prettiest of our girls. That’s when I decided I loved my new hairstyle, the cut, the color, and most of all, the attitude.

We planned to leave on Friday. I wasn’t going to pack much. Instead I would buy some new outfits during the trip. I’d lost an additional six pounds this week. Six pounds in a week! The first few days I’d been so sore I could hardly move. But there’s nothing like success to make pain insignificant. By Friday I meant to lose two more pounds, and along the trip I hoped to lose another three or four. At least I would have met my twenty-pound goal. And I’d still have another week in New Orleans before the actual reunion. Maybe five more pounds?

In between exercise sessions, during all the free time I had left over from my five-minute meals, I’d made arrangements for the housekeeper and gardener. Their checks were already written for Jack to dispense. The refrigerator was stocked with everything he liked, and all he had to do was feed the cat, feed himself and put his dirty clothes in the bathroom hamper.

As I watched him drive off to work that Friday morning, it occurred to me how easy his home life was. No decisions, no responsibilities. He provided the paycheck, and in return he lived here and expected that his every need would be taken care of. I suppose it’s the fulfillment of the contract we made when we said “I do.”

I have a degree in early childhood education, and I taught two years before Jennifer was born. But for the past twenty-five years I’ve been a stay-at-home mom with no complaints from him. Or from me. Jack is a wonderful provider and I also have income from my trust fund, which I use mainly to build up the girls’ trust funds.

But he’s unhappy. I’m sure of it. And I must be, too, if I’m driving two thousand miles and torturing myself to lose weight just so I can see Eddie Dusson smile when he sees me.

I hugged my arms around myself as Jack’s Lexus turned the corner and disappeared. He’d given me a quick kiss—a peck, really—and told me to have a good time. Then he’d gone to work.

I gnawed on my left thumbnail. Maybe I should worry more about impressing Jack than impressing Eddie.

Maybe I shouldn’t be going on this harebrained trip at all.

Then M.J. and her big champagne-colored cat of a car came purring down the street with Fats Domino blaring “Walking to New Orleans,” and my decision was made. I was eighteen again, going on a road trip with my two best girlfriends, and we were going to have a blast.

I fitted my suitcases next to theirs in the trunk, loaded three plastic containers of cut fruit into the ice chest alongside all the bottled water and slid a six-pack of toilet tissue under the seat. I had baby wipes, too, for the nasty truck-stop bathrooms we were sure to encounter, especially if we drank all that water.

“I brought lots of nail polish,” M.J. said. “We can do pedicures and manicures and we’ll stop in Dallas to get new outfits.”

“Don’t you mean Houston? I don’t think Dallas is along I-10,” I said.

“The fact is,” Cat said, “We can do whatever the hell we want.” She gave me a devilish grin, then handed me a pair of sunglasses, cat-eyed glasses with navy-blue lenses and a V of diamonds at each corner. “I’ll be Patrick Swayze, you be Wesley Snipes, and M.J. can be John Leguizamo. Like in Wong Foo,” she added when I gave her a confused look. “We’re going glamorous and we’re going to leave people staring after us as we go by.”

What we got was a speeding ticket before we were barely out of the Bakersfield city limits.

Of course, we didn’t actually get the ticket, because M.J. and her fabulous chest were at the wheel. But it wasn’t a testosterone-driven C.H.I.P who went gaga at the sight of my gorgeous pal. It was an estrogen-deprived female motorcycle cop, pretty but butch, and not much older than my daughters. She gave us a tolerant lecture, warned us to slow down and left before we did.

“Well,” M.J. said. “That was a first. I charmed a lesbian cop.”

“I told you. This is Wong Foo—the Lesbian Version,” Cat said.

“Except that none of us are homosexual. Are we?” I added.

“Oh, no,” Cat said. “I like men. They’re usually lousy men, but nevertheless, they’re men.”

“But if I did like women,” M.J. said as she pulled back onto the interstate, “I would have liked her. She had the prettiest complexion and a cupid’s bow mouth. Did you notice?”

“Especially when she said ‘I’ll let it go this time,’” Cat added from the front passenger seat. “You know, I wonder why we get turned on by the people we do. I mean, not just straight or gay, but why one guy and not another? Why do I always pick charming jerks? Why does M.J. like sugar daddies, and Bitsey like…” She swiveled around to look at me. “Come to think of it, I don’t know what your type is, Bits. I mean, Jack is such a regular hardworking kind of guy.”

“Whom you do not like,” I reminded her.

“Only when he takes you for granted. So Bits, what is your type?”

I put on my cat-eyed glasses. “I don’t know. Maybe I don’t have a type.”

“What about that old boyfriend you mentioned? He was your type in high school. Was he like Jack?”

No. Eddie was nothing like Jack. In many ways he was the exact opposite. He’d been the boy from the wrong side of the tracks, the public school hood who had fascinated the good little Catholic schoolgirl I’d once been.

“Eddie was wild,” I said, mainly to placate Cat. “And I was a good girl.”

She laughed. “You still are.”

There was nothing wrong with being good, with doing the responsible thing. Even so, her words hurt. “I’m sorry I’m so boring.” I looked out the window, at the fields of citrus trees in rigid green rows.

“I didn’t say you were boring.” She turned around to look at me. “Bits, that’s not what I said or what I meant.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Obviously it does.” She reached back and tugged on my skirt. “Is that what this Eddie said when y’all broke up? That you were too boring for a hotshot like him?”

That fast my anger bled away. How could I be angry with Cat? She was my friend, and I knew she loved me. In some ways she even envied me. Stylish, successful, career-woman Cat envied plump mother and housefrau Bitsey. I looked at her and smiled. “He didn’t say those exact words, but I knew that’s what he meant. I think maybe by then the novelty of dating a rich society girl had worn off.”

M.J. glanced back at me. “I knew you went to private schools. But you were a rich society girl?”

Shoot. I hadn’t meant to say that. On the other hand, they’d figure it out the minute they saw Daddy’s three-story cottage. So I told them my story, all except for the part about Mother committing suicide because no matter how many accolades she received for her work, it was never enough.

“You were queen of a Mardi Gras ball?”

“Proteus,” I admitted. “And a maid for two others. But it was a big pain and I wouldn’t wish it on any of my girls.”

“Wow,” Cat said. “And you’re so not a snob.”

“Debutante does not mean snob,” I said. “Check your Funk & Wagnall’s.”

M.J. hadn’t said much, but I could tell she wasn’t just concentrating on her driving. We were in a dry stretch of land now, all sand and dried-out everything

“Would you like some water?” I asked her.

“That would be nice.”

“You know, although we’ve been friends for a long time, we never really told each other about our growing-up years. I know why I never said too much about it, because I didn’t want y’all to think I was some rich snob. But why don’t either of you talk about your childhoods?”

“Because mine was lousy,” Cat said. “And I don’t want to relive it.”

“You already know about mine. I was the beauty queen, from about age two to twenty-one. Then I came to California.”

I stared at the back of their heads, M.J.’s dark shiny ponytail and Cat’s impeccable blond bob. “This isn’t fair. There’s a reason y’all decided to go back to New Orleans now, and it has nothing to do with my high school reunion. So tell the truth.” I crossed my arms. “We’re in this together, aren’t we?”

M.J. glanced at Cat, then back at the road. Finally she caught my eye in the rearview mirror. “Okay. I mean, it’s no secret. I need to get away from Frank’s kids and hide the money and car from their greedy hands. I have a few friends I can visit, and…I need time to think about what I’m going to do next.”

Cat laughed at her. “What Bitsey wants to know—what we both want to know, is who’s the first guy you plan to look up? An old boyfriend. Who’s your Eddie? That football guy you told me about?”

A smile brought out M.J.’s dimples. “I suppose he is. My Eddie is a guy named Jeff. Jeff Cole, star running back for the John Curtis Patriots.”

I shifted to the side and pulled my feet up under me. “Now we’re getting somewhere.”

“Don’t get all excited,” M.J. said. “I doubt he’s in New Orleans anymore. He got a football scholarship to Ole Miss and then played pro ball for a few years. I don’t know where he is now.”

“Is that who you lost your virginity to?” Cat asked.

“Yes,” M.J. admitted.

Then Cat looked at me. “And Eddie was your first?”

Slowly I nodded. Then M.J. and I both looked expectantly at Cat.

“Okay, okay,” she said. “If you must know, I sacrificed my cherry to Matt Blanchard.” She twisted the top off her bottle and took a long drink. “On a picnic blanket on the banks of Bayou Segnette with mosquitoes biting our asses. Classic, don’t you think?”

M.J. laughed. “So why did you two break up?”

Cat shrugged. “Because I couldn’t wait to blow town, and he was planning to stay forever.”

“Who’s the first person you’re going to call when we get there?” I asked her. “Matt?”

She took a long time answering. The tires hummed along the road.

“No. Not Matt. For all I know, he’s married with a houseful of kids. I’ll probably call my sister first.”

“Not your mom?” M.J. asked.

“No. Not my mom.”

“Why not?” I saw Cat’s jaw tense and release. Her mom is a sore point with her, but I wasn’t letting her get away with being evasive anymore.

She let out a long whoosh of a breath. “Okay. If you can admit you were once a debutante, I guess I can admit that I was born trailer trash.”

For a moment I was struck dumb, not from what she said, but how she said it. There was such contempt in her voice. Loathing, even.

“Trailer trash,” M.J. repeated. “You know, I hate that term. It’s like people always have to find a shorthand way to categorize people. Dumb blonde. Trailer trash. Beauty queen. Trophy wife. They categorize you because it makes it easier to dismiss you. Debutante, too,” she added. “Society deb.”

All of a sudden she laid on the horn, I mean mashed it over and over, all the while tearing southeast on the interstate doing at least eighty-five. “Make way for the Trophy Wife, Trailer Trash, Debutante Express! Look out world, ’cause ready or not, here we come!”

We squealed and cheered and laughed until our sides ached. It was a good thing our butch C.H.I.P. wasn’t around, because this time she would have hauled us straight to jail.

“We need to find a rest stop,” Cat pleaded. “I have to pee.”

Which sent M.J. into fresh whoops of laughter. “Well said, trailer trash. You need to pee, but I need the little girls’ room.”

“Oh, you trophy wives are all the same,” I put in. “You never grow up. What this debutante needs is a powder room. And fast.”

We found one, and none too soon. Of course, after we relieved ourselves, M.J. made me walk from one end of the rest stop to the other, the entire time goading me to go faster. Faster. She said it was about a mile round trip, but in the desert heat it felt like five. I did it, though, and when we stopped two hours later for lunch, I gobbled up a huge Cobb salad with fat-free ranch dressing.

Cat drove the next leg. We meant to reach Phoenix by dusk and get a hotel with a nice health club. Three to a room would keep it reasonable. Though I’d consumed probably less than four hundred calories at lunch, I was still halfway into a torpor when Cat said, “So, are we going to visit Margaret?”

I blinked away the beginnings of a nap. “Maybe.”

“Maybe?” M.J. turned around to study me. “The perfect mom doesn’t want to see her daughter whom she hasn’t seen in months?”

Why did that make me feel so guilty? Because it was true. “I’m planning on calling, but she may be too busy to see us. She works evenings. Besides, if I see her I’ll only worry about her.”

“You’ll worry anyway, so I say we go see her. Okay, Cat?”

“Okay with me. We can go to the club where she works. Maybe I can pick up some young studly college boy. I’ve been thinking that what I need is a trophy husband.”

M.J. laughed. “Sorry, darling, but it doesn’t work that way. Trophy husbands are old and wrinkled and very, very rich.”

“Like Frank.”

“Like good old Frank.”

“Is that what you want again, M.J?” I asked. “A trophy husband?”

“I think she should hook up with Mr. Football,” Cat said. “What was his name?”

“Jeff Cole.” M.J. smiled and hugged her knees. Damn, but that girl was limber. “Wouldn’t that be great if my first real boyfriend was rich and still available?”

“We should try to find out,” Cat said. “Bitsey gets to meet up with Eddie at her reunion. You could call Mr. Football.”

“And what about you?” she asked. “Are you going to look up Mr. Stick in the Mud?”

“Matt,” Cat said. “Sheriff Matt Blanchard, according to one of my mother’s infrequent Christmas cards.”

“He’s a sheriff?”

“Of my old hometown. Mais, I tol’ you, he’s a good ol’ boy,” she said, slipping into a thick Cajun accent. “He prob’ly has a passel of kids by now, cher, an’ a kennel of hunting dogs, an’ a gun rack in his pickup truck.”

“I bet he chews tobacco,” M.J. said.

“And has a beer belly,” I put in.

“And hates uppity women,” Cat said. “Maybe I will look him up, just to be mean.”

From the back seat I considered just what we were doing in M.J.’s semistolen Jaguar on our way cross-country to New Orleans. I was going to my high school reunion because I wanted to see Eddie. I couldn’t explain why. I’m happily married, although I’m not so sure my husband is. The fact remained, however, that I wasn’t in the market for another man. But M.J. and Cat, my two very best friends, could each use a decent guy in their lives.

I unfastened my seat belt and scooted forward so that my head was even with theirs. “Listen to us,” I said. “We’ve all admitted that we have these unresolved relationships with our old boyfriends. Maybe there’s a reason we’re making this trip together. Maybe we’re supposed to resolve them. You and Jeff.” I squeezed M.J.’s shoulder. “And you and Matt.”

Cat fixed me with a narrow gaze. “And you and Eddie?”

I sat back. “Maybe.”

“You would cheat on your husband?” M.J. asked.

“I didn’t say that. God, you have your minds in the gutter. What I’m saying is that things are not…wonderful between me and Jack. I just need some perspective.”

“I say go for it,” Cat said.

“I will if you will,” I said right back.

M.J. frowned. “I don’t know if Jeff is even in New Orleans.”

I grinned. “I bet Margaret can find out for us.”

“Margaret?”

“The Internet. If he was a football player and later a coach, she can probably find out where he is now.”

“Maybe there will be something about the good sheriff, too,” Cat said. “And Eddie Dusson.”

It was decided then. Ahead of us the southern tail of the Rockies formed a jagged line on the horizon. But we would be driving over them and through them, and at the end of our journey we would find the girls we used to be—and maybe the boys we once upon a time loved.