Читать книгу Weird Tales #360 - Рэй Брэдбери - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE LONG LAST NIGHT

BY BRIAN LUMLEY

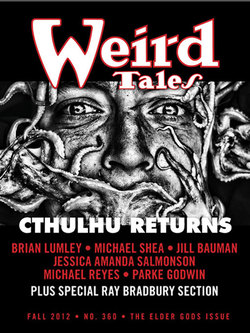

ОглавлениеBorn 2nd December, 1937, Brian Lumley came into the world just nine months after the most obvious of his forebears—meaning of course a “literary” forebear, namely, H. P. Lovecraft—had departed from it. In his early teens, as a result of reading Robert Bloch’s Lovecraft pastiche Notebook Found in a Deserted House, he became more surely attracted to macabre fiction, an attraction that has lasted a lifetime. HPL’s publisher August Derleth asked Lumley, whom he knew to be an aspiring author, whether he had anything solid he could use in a book he was preparing for publication, to be entitled Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Thus Lumley began writing in earnest. Derleth included stories by Lumley in a number of Arkham House anthologies and went on to publish three of the author’s books, Beneath the Moors; The Caller of The Black and The Horror at Oakdeene, all set mainly in Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos milieu and echoing HPL’s literary style. After 22 years in the British military, Lumley became “a professional author” (he had never really considered himself that before) and began to write in earnest. His breakthrough book was the ground-breaking horror novel Necroscope®, featuring Harry Keogh, the man who can talk to dead people; it became a best-selling series. Thirteen countries (and counting) have now published, or are in the process of publishing these and others of Lumley’s novels and short story collections, which in the USA alone have sold well over three million copies. In addition, Necroscope comic books, graphic novels, a role-playing game, quality figurines, and in Germany a series of audio books have been created from themes and characters in the Necroscope books, and Lumley has added his “real” voice to Dangerous Ground, a Downliners Sect rock & roll album released in the UK in 2004. In March 2010 Brian received the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award from the Horror Writers Association. This was presented to him at the World Horror Convention in Brighton, UK. HPL’s most accomplished successor, Mr. Lumley helps launch the Elder Gods issue of Weird Tales with the following frightening science-fictional version of tomorrow’s London.

I met or bumped into the old man on what was probably the very rim of the Bgg’ha Zone. And after careful, nervous greetings (he had a gun and I didn’t) and while we shared one of my cigarettes, he asked me: “Do you know why it’s called that?”

He meant the Bgg’ha Zone, of course, because he’d already mentioned how we should be extremely careful just being there. Shrugging by way of a partial answer, I then offered: “Because it’s near the center of it?”

“Well,” he replied, “I suppose that defines it now. I mean that’s likely how most people think of it; because after three or four years a name tends to stick, no matter its actual origin. And let’s face it, there’s not too many of us around these days—folks who were here at the time, old’uns like myself—who are still here to remember what happened that time.”

“When the Bgg’ha Zone got its name, you mean?” I prompted him. “There’s a reason it’s called that? So what happened?”

Getting his thoughts together, he nodded, and finally said, “The real reason is that shortly after that damn twisted tower was raised not long after they first got here, after they came down from the stars and up from the sea, or whatever, the only time anyone went anywhere near the twisted tower voluntarily—‘to find out what it was like!’ I’ve heard it said, if you can credit anyone would do such a thing!—the damn fool came out again a ragged, shrieking lunatic who couldn’t do anything but scream a few mad words over and over again. ‘The Bgg’ha Zone!’ he would scream while he laughed, skittering around and pointing at that mile-high monstrosity where it stands dead centre of things; and: ‘The twisted tower!’ he’d yelp like a dog. But he was harmless except to himself, and it was all he did until they gagged him to stop all his noise. Then his heart gave out and he died with the froth of madness drying on his lips … ”

“You talk too much and too loudly,” I told him. “And if I really should be as afraid of this place as you make out, then what in God’s name are you doing here?” Before he could answer, I shook another Marlboro from its pack, lit it, took a drag and handed it to him. I had no reason to antagonize the old boy.

“God’s name?” He turned his head and stared at me where we sat amidst the rubble, on the remains of a toppled brick wall; stared at me with his bloodshot eyes—his sunken, crying eyes that he’d rubbed until they were a rough, raw red—before accepting and sucking on that second cigarette. And: “Oh, I have my reasons for being here” he said. “Nothing to do with God, however. Not the God we used to pray to, anyway … not unless I’m here as His agent, sort of working for Him without really knowing it—in which case He might have chosen a better way to set things up!”

“You’re not making a lot of sense,” I told him, “and you’re still much too noisy. Won’t they hear you? Don’t they sometimes patrol outside the Bgg’ha Zone? I’ve heard they do.”

“Patrols?” He took a deep drag, handed my smoke back to me, and went on: “You mean hunters? And do you know what they hunt? They hunt us! We’re it! Meat!”

Then, after another drag and a sly, sidelong glance at me, from eyes still bloodshot but narrowed now: “Anyway, and like I said, I have a good reason for being here. A damn good reason!” And he balanced a small, battered old suitcase on his knees and hugged it to him, but not too tightly. It looked very heavy for its size.

“So then,” he nodded again. “I reckon it’s your turn now to tell why you are here. I never saw you before and I don’t think you’re from the SSR … so?”

“The SSR?”

“The South Side Resistance, for what they’re worth—huh!” he answered; but I was watching his veined right hand moving to rest on the gun at his bony hip. And again he asked, “So?”

“I stay live by moving around,” I told him. “I don’t stay too long in any one place, and I live however I can. I go where there’s food, when and where I can find it, and cigarettes, and on rare occasions a little booze.”

“The old grocery stores? The shattered shops?”

“Yes, of course.” My turn to nod. “Where else? The supermarkets that were. Those that aren’t already completely looted out. In the lighter hours—the few short hours of partial daylight, when those things sleep, if they sleep—I dig among the ruins; but stuff is getting very hard to find. Day by day, week by week, it’s harder all the time. Landed here just a couple of days ago. Least I think it was days; you never can tell in this perpetual dusk. I haven’t seen the sun for quite some time now, and even then it was very low down on the horizon, right at the beginning of this … this—”

“—This long last night?” he helped me out. “The long last night of the human race, and certainly of Henry Chattaway.”

Then he sobbed, and only just managed to catch it before it leaked out of him, but I heard it, anyway. And: “My God, how and why did this bloody mess happen to us?” And craning his neck he looked up to where black wisps of cloud scudded across the sky, as if searching for an answer there … from God, perhaps.

“So—er, Henry?—in fact you are a believer,” I said, standing up from the broken wall and dropping my smoke before it could burn my fingers. “So, are we sinners, do you reckon?” And I stepped on the glowing tobacco embers, crushing them out in the powdered, brick-red dust.

Controlling his breathing, his sobbing, the old man said, “Do you mean are we being punished? I don’t know—probably. Come with me and I’ll show you something.” And getting creakingly to his feet, he went hobbling to a more open area close by, once the corner of a street—more properly a function of twisted blackened ruins and rubble now—where the scattered, shattered debris lay more thinly on the river ground, and only the vaguest outlines of any actual street remained. Of course, this was hardly unusual; for all I knew the entire city—and probably every city in the world—would look pretty much the same right now.

The old man tugged on the sleeve of my parka where I stood glancing here and there, aware that at this once-crossroads we would be plainly visible from all four directions. But my companion was pointing toward the northeast; so that even before my eyes followed the bearing indicated by his scrawny arm, his trembling finger, I knew what I would see. And:

“Look at that!” He uttered a husky whisper, almost a whimper. And once again, “Look!” as he tugged more insistently on my arm. “Now tell me: isn’t it obvious where at least one of those names comes from?”

He was talking about the twisted tower—a “mile-high monstrosity,” he’d called it –where it stood, leaned or seemed to stagger, perhaps a mile away, or a mile and a half at most. But matching it in ugliness was its almost obscene height … not a mile high, no, but not far short; with its teetering spire stabbing up through the disc of cloud that had been drawn there and now circled it like a whirlpool of the debris of doomed plants round the sucking well of a vast black hole. It was built of the wreckage, the ravaged soul of the crushed city; of gutted high-rises; of several miles of railway carriages twined around its fat base and rising in a spiral, like the thread of a gigantic screw, to a fifth of the tower’s height; of bridges and wharves torn from their anchorages; of a great round clock face, recognizable even at this distance as that of Big Ben; of a jutting tube concrete and glass that had once stood in the heart of the city where it had been called Centrepoint … all of these things and many more, all parts now of this twisted tower. But it wasn’t really twisted; it was just that its design and composition were so utterly alien that they didn’t conform to the mundane Euclidean geometry that a human eye or brain would automatically accept as the shapes of a genuine structure, observing them as authentic, without feeling sick and dizzy.

And though I had seen it often enough before, still I took a stumbling step backwards before tearing my eyes away from it. Those crazy angles, which at first seemed convex before concertinaing down to concavities … only to bulge forth again like gigantic boils on the trunk of a monster. “That mile-high monstrosity,” yes; but I had seen it before, if not from this angle, and I’d known what effect it would have on me; so I’d been far more interested in what stood—seeming almost to teeter—in front of it, as if in some kind of obeisance:

It leaned there close to that colossal, warped dunce’s cap, out of true at an angle of maybe twenty degrees, only a hundred yards of so in the tower’s foreground; and instead of the proud dome that it had been, it now looked like half of a blackened, broken egg, or the shattered skull of some unimaginable giant, lying there in the uneven dirt of a vast, desecrated graveyard: the dome of St. Paul’s cathedral.

“Horrible, horrible,” the old man said and shuddered uncontrollably—then gave a start when, from somewhere not very far behind us, came a dismal baying or hooting call; forlorn-sounding, true, but in the otherwise silence of the ruins terrifying to any vulnerable man or beast. And starting again—violently this time as more hooting sounded, but closer and from a different direction—the old man said, “The hounds! That howling is how they’ve learned to triangulate. We’ve got to get away from here!”

“But how?” I said. “The howling’s from the south, while to the northeast … we’re on the verge of the Bgg’ha Zone!”

“Come with me—and hurry!” he replied. “If some of these wrecked buildings were still standing we’d already be dead—or worse! The hounds know all the angles and move through them, so we can think ourselves lucky.”

“The angles!”

“Alien geometry,” he answered, limping as fast as he could back down the rubble canyon where we’d met, then turning into a lesser side-street canyon. And panting, he explained: “They say that where the hounds come from—Tindalos or somewhere—something?—there are only angles. Their universe is made of angles that let them slip through space and they can do the same here. But London has lost most of its angles now; and with the buildings reduced or rounded and jumbled heaps of debris, the hounds have trouble finding their way around. And whether you believe in Him or not, you may thank God for that!”

“I’ll take your word for it,” I said, certain that he told the truth. “But where are we going?”

“Where I intended to be going anyway,” he replied. “But you most probably won’t want to—for which I don’t blame you—and anyway we’re already there.”

“Where?” I said, looking left, right, everywhere and seeing nothing but heaped bricks and shadowy darkness.

“Here,” he answered, and ducked into the gloom of a partly caved-in iron and brick archway. And assisted by a rusted metal handrail, we made our way down tiled steps littered with rubble fallen from the ceiling, lying there under a layer of dust that thinned out a little the deeper we went.

Where are we?” I asked him after a while. “I mean, what is this place?” My questions echoed while the gloom deepened until I could barely see.

“Used to be an old entrance of the tube system,” he told me. “This one didn’t have elevators, just steps, and they must have closed it down a hundred years ago. But when these alien things were rioting through the city, causing earthquakes and wrecking everything, all of the destruction must have cracked it open.”

“You seen to know all about it,” I said, as I became aware that the light was improving; either that or my eyes were growing accustomed to the dark.

The old man nodded. “I saw a dusty old plaque down here one time, not long after I found this place. A sort of memorial, it said that the last time this part of the underground system was used was during the Second World War—as a shelter. It was too deep down here for the bombs to do any damage. As for now, it’s still safer than most other places, at least where those hounds are concerned, because it’s too round.”

“Too round?”

“It’s a hole in the earth deep underground,” he replied impatiently. “It’s a tunnel—a tube—as round as a wormhole!”

“Ah! I said. I see. It doesn’t have any angles!

“Not too many, no.”

But it does have light, and it’s getting brighter.”

We passed under another dusty archway, and were suddenly on the level: a railway platform, of course. The light was neither daylight or electric; dim and unstable it came and went, fluctuating.

“This filth isn’t light as you know it,” the old man said. “It’s shoggoth tissue, bioluminescence, probably waste elements, or shit to you! It leaks down like liquid from the wet places. Unlike the hideous things that produce it, however, those god-awful shoggoths, it’s harmless. Just look at it up there on the ceiling.”

I looked, if only to satisfy his urging, at a sort of glowing mist that swirled and pulsed as it spilled along the tiled, vaulted ceiling. Gathering and dispersing, it seemed tenuous as breath on a freezing cold day. And:

“Shoggoth tissue?” I repeated the old fellow. “Alien stuff, right? But how is it you know all this? And I still don’t even know why you’re here. One thing I do know—I think—is that you’re going the wrong way.”

For he had got down from the platform and was striking out along the old rusted tracks that my sense of direction told me were heading –

“Northeast!” he said, as if reading my mind. “And I warned you that you wouldn’t be safe coming with me. In fact, if I were you I’d follow the rails going the other way, south; and sooner or later, somewhere or other, I’m sure you’ll find a way out.”

“But I’m not at all sure!” I replied, jumping down from the platform and hurrying to catch up. “Also, it’s like I said: you seem to understand just about everything that goes on here, and you’re obviously a survivor. As for myself, I’d like to survive, too!”

That stopped him dead in his tracks. “A survivor, you say? I was, yes—but no more. My entire family is no more! So what the hell am I doing trying to stay alive, eh? I’m sick to death of trying, and there’s only one reason I haven’t done away with myself!” And that catch was back in his voice, that almost sob.

But he controlled it, then swung his small, heavy, battered old suitcase from left to right and changed hands—groaning as he stretched and flexed the strained muscles in his left arm—before swinging the suitcase back again and visibly tightening his grip on its leather handle.

“You should let me carry it,” I told him, as we began walking again. “At least let me spell you. What’s in it, anyway? All your worldly possessions? It looks heavy enough.”

“Don’t you worry about this suitcase!” he at once snapped, turning his narrow-eyed look on me as his right hand fell once again to the butt of the weapon on his hip. “And I still think you should turn around and head south while you still can—if only … if only for my stupid peace of mind!— ” (As quickly as that he softened up) “—because I can’t help feeling guilty that it’s my fault you’re here! And the deeper we get into the Bgg’ha Zone, the more likely it is you won’t get out again!”

“Don’t you go feeling guilty about me,” I told him evenly. “I’ll take my chances, like I always have. But you? What about you?”

He didn’t answer, just turned away and carried on walking.

“Or maybe you’re a volunteer—” I hazarded a guess, though by now it was becoming more than a guess “—like that first one who went in and came out screaming? Is that it, Henry? Are you some kind of volunteer, too?” He made no answer, remained silent as I followed on close behind him.

And feeling frustrated in my own right, I goaded him more yet: “I mean, do you even know what you’re doing, Henry, going headlong into the Bgg’ha Zone like this?”

Once again he stopped and turned to me … almost turned on me! “Yes,” he half-growled, half-sobbed, as he pushed his wrinkled old face close to mine. “I do know what I’m doing. And no, I’m not some kind of volunteer. What I’m doing—anything I do—is for myself. You want to know how come I know so much about what happened around here, and to the planet in general? That’s because I was here, pretty much in the middle of it; the middle of one of the centres, anyway. And you’ve probably never heard of them, but there was this crazy bunch … the Esoteric Order, or some such … they had their own religion, if you could call it that, their own church where they gathered; and their bibles were these cursed, moldy old volumes of black magic and weird alien spells and formulas that should have been destroyed back in the dark ages. Why, I even heard it said that. … ” But there he paused, cocking his head on one side and listening for something.

“What is it?” I asked him. Because all I could hear was the slow but regular drip, drip, drip of seeping water.

Then, with a start, a sudden jerk of his head, the old man looked down at the rusting rails, where three or four inches of smelly, stagnant water glinted blackly as it slopped between the tube’s walls. And: “Shh!” he whispered. “Listen, damn you!”

I did as I was told, and then I heard it: those faintest of hollow echoes; a distant grunting, muttering, and slap-slapping of feet in the shallow pebbles back where we had come from. But the grunted—or gutturally spoken—sounds were hardly reassuring, and definitely not to my companion’s liking.

“Damn you! Damn you!” the old man whispered. “Didn’t I warn you to go back? You might even have made it in time before they came on the scene. But you can’t go back there now!”

Just the tone of his hoarse voice made my flesh creep. “So what is it?” I queried him again. “Who or what are ‘they’ this time?”

“We have to get on,” he replied ignoring my question. “Have to move faster—but as quietly as we can. Their hearing isn’t much to speak of, not when they’re up out of their element, the water—but if they were to hear us … ”

“They’re not men?”

“Call them what you will,” he told me, his voice all shuddery. “Men of a sort, I suppose—or frogs, or fish! Who can say what they are exactly? They came in from the sea, up the Thames and into the lakes and wherever there was deep water. It was as if they had been called … I’m sure they were called! By those crazies of the Esoteric Order. But true men? Not at all, not in the least! Their fathers must have mated with women, definitely—or vice versa, maybe?—but no, they’re not men … ”

Which prompted me to ask: “How can you know that for sure?”

“Because I’ve seen some of them. Just the once, but it was enough. And you hear that slap-slapping? Can’t you just picture the feet that slap down on the water like that? Good for swimming, but of small use for walking.”

“So why are we in such a hurry?”

And once more impatiently, or yet more impatiently, he said, “Because they can call out others of their kind. A sort of telepathy, maybe? Hell, I don’t know!”

We moved faster, and I could hear him wincing each time our feet kicked up water that splashed a little too loudly. Then in a while we came across a narrow platform to one wide, where the wall had been cut back some two feet to make a maintenance walkway four feet higher than the bed of the tracks.

“Get up there,” the old man told me. “It’s dry and we’ll be able to go faster without all the noise.”

I did as he advised and reached down to help him up. He was little more than a bundle of bones and couldn’t be very strong, but he didn’t for a second offer that case to me or release his grip on it. And so we moved ahead, him front, me behind; and eventually—this time without my urging—he continued telling me his story from where he’d left off; his story, plus that of the alien invasion or takeover; or walkover, which seemed to come much easier to him now. So maybe he’d needed to get it off his chest.

“It was those Esoteric Order freaks. At least, that was how everyone thought of them: as folk with too few screws, and what few they had with crossed threads! But no, they weren’t crazy except maybe in what they were trying to do. And actually, that even got into the newspapers: how the Esoteric Order was trying to call up powerful creatures—god-things, they called them—from parallel dimensions and the beginning of time; beings that had come here once before, even before the evolution of true or modern Man, only to be trapped and poisoned by yet more mysterious beings and banished back to their original universes, or to forgotten, forbidden places here on Earth …

“Well, it was a laugh, wasn’t it?” As daft as all those UFO stories from more than a century ago, and tales of prehistoric monsters that lived in a Scottish loch and on Himalayan mountains; oh, and lots of other myths and legends of that sort. Oh really? And if the oh-so-bloody-clever newspaper reporters who infiltrated the church and saw them at their worship and listened to their ‘idiotic beliefs’—if they had been right, then all well and good … but they weren’t!

“And when should it happen—when did it happen—but at Hallowmas? The feast of All Hallows, All Saints!

“And oh, what an awful feast that was, them feasting on us, I mean, when those monstrous beings answered the call and came forth from strange dimensions, bringing their thralls, servitors and adherents with them. Up from the oceans, down from the weird skies of parallel universes, erupting from the earth and bringing all of the planet’s supposedly dead volcanoes back to life, these minions of madness came; and what of humanity then, eh? What but fodder for their tables, fodder for their stables.”

That last wasn’t a question but a simple fact, and the old man was sobbing again—openly now—as he turned and grasped my arm. “My wife … ” he almost choked on the word. “That poor, poor woman … she was taken at first pass! Taken, as the city reeled and the buildings crumbled, as the earth broke open and darkness ruled … !

“Ah, but according to rumor, the very first to go was that blasphemous, evil old church; for the so-called priests of the Esoteric Order had been fatally mistaken in calling up that which they couldn’t put down again: a mighty octopus god-thing who rose in his house somewhere in the Pacific, while others of his spawn surfaced in their manses from various deeps. Not the least of them emerged somewhere in the Arctic Circle along with an entire plateau; that was a massive upheaval, causing earthquakes and tsunamis around the world! Another rose up from the Mariana Trench, and one far closer to home from a lesser known abyss somewhere in the mid-Atlantic. He was the one—damn him to hell!—who built his twisted tower house here in the zone.

In fact the Bgg’ha Zone is named after him, for he is Bgg’ha!

“And there’s a chant, a song, a liturgy of sorts that human worshippers—oh yes, there are such people!—sing of a night as they wander aimlessly through the rubble streets. And having heard it so often, far too often, dinning repeatedly in my ears while I lay as if in a coma, hardly daring to breathe until they had moved on, I learned those alien words and could even repeat them. What’s more, when the SSR trapped and caught one of these madmen, these sycophants, to learn whatever they could from him, he offered them a translation. And those chanted words which I had learned, they were these:

“Ph’nglui gwlihu’nath, Bgg’ha Im’ykh i’ihu’nagl fhtagn.” A single-made sentence that translates into this:

“From his house at Im’ykh, Bgg’ha at last is risen!”

“And do you know, those words still ring in my ears, blocking almost everything else out? If I don’t concentrate on what I’m doing, on what I’m saying, it all slips away and all I can hear is that damned chanting: Bgg’ha at last is risen! And perhaps I even have … I even have the means with which to do it … ”

But there the old man fell silent once more, possibly wondering if he’d said too much …

Then, as we rested for a few minutes, and as I looked down from the maintenance ledge, I saw how the dirty water glinting between the rusted rails was much deeper here, perhaps as much as ten or twelve inches. Seeing where I was looking, my companion told me:

“Yes, there’s very deep water up ahead, and likewise on the surface.”

Ahead of us?” I repeated him for want of something to say. “But … on the surface?”

“Mainly on the surface,” he nodded. “That’s where it’s leaking from. We’re heading for Knightsbridge, as was—which isn’t far from the Serpentine—also as was but much enlarged and far deeper now. That, too, was the work of Bgg’ha; he did it for some of his servitors, the kind we heard wading through that shallow water back along the tracks. There’s plenty more of them in the Serpentine, which is part of a great lake now that’s drowned St. James’s Park and everything in between all the way to the burst banks of the Thames. We can stay down here for another mile or thereabouts, but then we’ll have to surface … either that or swim, and I really don’t fancy that!”

“You’ve done this before,” I said as we set off again, because it was obvious that he had, and fairly often or recently. That explained how he knew these routes so well.

He nodded and replied, “Five times, yes. But this is going to be the last. For you, too.”

“Or maybe not,” I replied. “I mean, you never can tell how things will work out.”

“You young fool!” he said, but not unkindly, even somewhat sadly. “You’ll be right in the heart of the Bgg’ha Zone. Right there, in the roots of the twisted tower, that loathsome creature’s so-called ‘house!’ And I can tell you exactly how things are going to work out for you: you won’t be coming out again!”

“But you did it,” I answered him. “And all of five times—if you’re not lying, or not simply crazy!”

He shook his head. “I’m not lying, and I’m not just crazy. You’re the one who’s crazy! Listen, do you have any idea who I am, or why I’m really here?”

I shrugged. “You’re just an old man on a mad mission. That much is obvious. I may even know what your mission is, and why. It’s revenge, because they took your wife, your family. But one small suitcase—even one that’s full of high explosives—just isn’t going to do it. Nothing short of a nuclear weapon is ever going to do it.”

The look he turned on me then was sour, downcast, and disappointed. And: “Have I been that obvious?” he asked me, as we came to a halt where the ledge widened out onto an actual platform. “I suppose I must have been. But even so, you’re only half right—and that makes you half wrong.”

The shoggoth light was poorer here, where the mist writhing on the tiled, vaulted expanse of the ceiling was that much thinner. Our eyes, however, had grown accustomed to the eerie gloom and the fluctuating quality of the bioluminescence, and we were easily able to read the legend on the tunnel’s opposite wall:

KNIGHTSBRIDGE

“My God!” my guide muttered then. “But I remember how this place looked in its heyday: so clean and bright with its shining tiles, its endless stairs and great elevators, its theatre and lingerie posters. But look at it now, with its evidence of earth tremors and fires: its blackened, greasy walls; its collapsed or caved-in archways; all the other damage it’s suffered. And … and … Lord, what a mess!”

A mess? Something of an understatement, that. The ceiling was scarred by a series of broad jagged cracks where dozens of tiles had come loose and fallen; some of the access/exit openings in the wall on our side of the tracks had buckled inwards, causing the ceiling to sag ominously where mortared debris and large blocks of concrete had crashed down; and from its source somewhere high above a considerable waterfall was surging out of an arched exit and spilling into the central channel, drowning the tracks under a foaming torrent.

As we clambered over the rubble, the old man said, “I think that I—or rather that we—are probably in trouble.” And I asked myself: another understatement? How phlegmatic! And meanwhile he had continued: “Like everywhere else, this place seems to be coming apart. It’s got so much … so much worse, since I was last here … ”

Which was when he began to ramble and sob again, only just managing to make sense:

“There’s been so many earthquakes recently … if the rest of the underground system is in the same terrible condition as this place … but then again, maybe it’s not that bad … and Hyde Park Corner isn’t so far away … not very far at all … and anyway it was never my intention to try surfacing here … there’s water up there … too much water … but still a half decent chance we can make it to Piccadilly Circus down here . . I’ve got to make it to Piccadilly Circus … right there under that monstrous twisted tower!”

Feeling that I had to stop him before he broke down completely and did himself some serious harm, I grabbed his arm to slow him down where he was staggering about in the debris, and shouted over the tumult of the water: “Hey! Old man! Slow down and try to stop babbling! You’ll wear yourself out both physically and mentally like that!”

As we cleared the heaped rubble it seemed he heard me and knew I was right. Shaking as if in a fever, which he might well have been, he came to a halt and said: “So close, so very close … but God! I can’t fail now. Lord, don’t let me fail now!”

“You said something about not intending to surface here,” I reminded him, holding him steady. “About maybe having to swim?”

At which he sat down on a block of concrete fallen from the ceiling before answering me. And as quickly as that he was completely coherent again. “Wouldn’t even try to surface here,” he said, shrugging his thin shoulders. “There’s far too much water up there—and too many of those monsters that live in it! But we must hope that the rest of the system, between here and Piccadilly Circus, is in better condition.”

“Is that where we’re heading?” I inquired, grateful for the break as I sat down beside him. “Piccadilly Circus, I mean? So how do we manage it? Will it mean getting down in the water?”

Swaying a little as he got to his feet, he looked over the rim of the platform before answering me. “Are you worried about swimming? Well don’t be. The water here isn’t nearly as deep as I thought it might be … I think it must find its way into the depths of the shattered earth, maybe into a subterranean river. So even though we won’t have to swim, still it appears we’ll be doing a lot more wading; knee-deep at least and maybe for quite a while. So now for the last time—even though it’s already far too late—I feel I’ve really got to warn you: if you want to live, to stand even a remote chance, you’ve got to turn back now! Do you understand?”

“I think so, yes,” I told him. “But you know, Henry, we’ve been lucky so far, both of us, and maybe it’s not over yet.”

“I can’t convince you, then?”

“To go back? No.” I shook my head. “I don’t think I want to do that. And the truth is, we all have to die some time. Whether it’s at Piccadilly Circus under the twisted tower or back there where those—those beings—were splashing about in the water; I mean, what’s the difference where, why, or how we do it, eh? It’s got to happen eventually.”

“As for me,” he said, letting himself down slowly over the rim of the platform into water that rose halfway up his thighs, “it is a matter of where I do it—where I can be most effective! My revenge, you said … and at least you were right about that. But you: you’re young, strong, apparently well-fed! Which is a rare thing in itself! You probably came in from the woods, the countryside—a place where there are still birds and other wild things you can catch and eat—or so I imagine. So for you to accompany me where I’m going … ” He shook his head. “It just seems a great waste to me.”

There was nothing in what he’d said that I could or needed to answer; so as I let myself down into the water beside him, I simply said, “So then, are you ready to move on?” And since his only reply was to lean his bony body into the effort—for the flow of the water was against us and strong—I added, “I take it that you are! But you know, Henry, pushing against the water like this will soon drain you. So may I suggest—only a suggestion, mind you—that you let me carry the case? If you want to do the job you’ve set yourself, whatever it is, that’s fine. But since I’m here, why not let me help you?”

He turned to me, turned a half-thankful, half-anxious look on me, and finally reached out with his trembling arms and gave that small heavy suitcase into my care. “But don’t you drop it in the water!” he told me. “In fact don’t drop it at all—or bank it around—or damage it in any way! Do you hear?”

“Of course I do, Henry,” I answered. “And I think I understand. I’ve seen how you take care of it, and it’s obvious how crucial it must be to your mission, whatever that turns out to be. Perhaps as we move along, you’d care to tell me about it—but it’s also fine if you don’t want to. First, though, if you don’t mind, could you get my cigarettes and lighter out of the top pocket of my parka?” For I was hugging the case to my chest with both hands, well above the water level. “The water’s very cold and a drag or two may help to warm us—our lungs, anyway. Light one up for yourself and one for me.” And when he had managed that: “Thanks, Henry,” I told him out of the corner of my mouth, before dragging deeply on the scented smoke.

He smoked, too … but remained silent on the subject of the suitcase, and in particular its secret contents.

I thought I knew about that, anyway, but would have preferred to hear it from him. Well, perhaps there was some other way I could talk him into telling me about it. So after we’d waded for another ten or twelve minutes and finished our cigarettes:

“Henry, you asked me a while ago if I had any idea who you are.” I reminded him. “Well not, I don’t, but it might pass some time and keep our minds active—stop them from freezing up—if you’d tell me.”

“Huh!” he answered. “It’s like you want to know everything about me, and I don’t even know your name!”

“It’s Julian,” I told him. “Julian Chalmers. I used to be a teacher and taught the Humanities, Politics and—of all things—Ethics, at a university in the Midland.”

“Of all … all things?” Shivering head to toe, he somehow got the question out. “How do … do you mean, ‘of all things’?”

“Well, they’re pretty different subjects, aren’t they? Sort of jumbled and contradictory? I mean, is there any such thing as the ethics of politics? Or its humanity, for that matter!”

He considered it a while, then said, “Good question. And I might have known the answer once upon a time. But then I would have been talking about—God, it’s c-cold!—about human politicians. And since the actions or mores of human beings don’t really apply any more—”

But there he’d paused, as if thinking it through. And so:

“Go on,” I quickly prompted him, because I was interested. And anyway, I wanted to keep him talking.

“Well, the invaders,” he obliged me, “I mean all of them—from their leaders, the huge tentacle-faced creatures in their crazily-angled manses, to the servitors they brought with them or called up after they got settled here—all the nightmarish flying things, and those shapeless, flapping-rag horrors called hounds—and not least those scaly half-frog, half-fish minions from their deep-sea cities—not one of these species seems to have ever evolved politics, while the very idea of ethics seems as alien to them as they themselves are to us! But on the other hand, if you’re talking human politics, human ethics—”

“I don’t think I was,” I said, then just as quickly let the subject drop as another maintenance ledge came into view on the left. We couldn’t have been happier, the pair of us, to get out of the water and up onto that ledge; and, somewhat surprisingly, we were relieved to discover that a welcoming draft of air from somewhere up ahead was strangely warm!

“Most places underground are like this,” the old man tried to explain it. “When you get down to a certain depth, the temperature is more or less constant. It’s why the Neanderthals lived in caves. It was the same the last time I was here, which I had forgotten about, but this warm air has served to remind me that we’ve reached—”

HYDE PARK CORNER

He let the legend on the brightly-tiled wall across the tracks finish the job for him, precisely and silently.

“So, what do you think?” I asked him, as we moved from the ledge onto the underground station’s platform. “How are we doing, Henry?”

“Not good enough,” he answered. “We should be doing a whole lot better! My fault, I suppose, because I’m not as strong as I used to be. I’m just too frail, too weak, that’s all, and I’m not afraid to admit it. It’s what happens when a man gets old. But that’s OK, and I can afford to push myself one last time. Because this will be the last time, my last effort in the long last night.”

“Hey, you’ve done okay up to now!” I told him. “And if this warm draft keeps up it will soon dry our trousers out. It’s not much, I suppose, but it may help keep our spirits up.”

He glanced at me, if only for a moment conjuring up a thin, sarcastic ghost of a smile, and with an almost pitying shake of his head said: “Well okay, good, fine!—whatever you say, er, Julian?—but now it’s my turn to spell you. So if you’ll just give that case back to me … ”

Not for a moment wanting to upset him, I handed it over and said, “Okay, if you’re sure you can handle it—?”

“I’m sure,” he told me, as we looked around the platform.

Things were nowhere as bad as Knightsbridge; there had been very little damage here, not on the actual platform, and when I looked down at the tracks I could see them glinting dully under no more than twelve or fifteen inches of water. But both of the arched exits were blocked with rubble fallen from above, making my next comment completely redundant:

“It seems there’s no way up, not from here.”

Henry nodded. “Not even if we wanted to surface here, which we don’t. Next up is Green Park, and following that—assuming we get that far—Piccadilly Circus. But Green Park is right on the edge of the water, and—”

“And that’s Deep One territory, right?” I cut in.

He nodded, frowned and narrowed his eyes, and said, “Well yes, I do believe I’ve heard them called that before … ”

“Of course you have,” I replied. “That’s what you called them, back there where they were splashing about in the water behind us.”

Still frowning, he shook his head and slowly said, “It’s a funny thing, but I don’t remember that.” And then with a shrug of his narrow shoulders: “Well, so what? I don’t remember much of anything any more, only what needs to be done … ”

And with one last look around he went on: “We have to get back down into the water. Just when we were drying out, eh? Be glad Green Park’s not far from here, only one stop. But it’s a hell of a junction, or used to be. It seems completely unreal, surreal now—like some kind of weird dream—but there were three lines criss-crossing Green Park in the old days. I still remember that much, at least … ” He gave himself a shake, and finally went on: “Anyway, for all that it’s close to the lake, it was bone dry the last time I was there. Let’s hope nothing has changed. And after Green Park, at about the same distance again, then it’s Piccadilly Circus—the end of the line, as it were. The end for us, anyway.”

His comment was loaded—the last few words definitely—but I ignored it and said, “And is that where we’ll surface?”

Again Henry’s nod. “It’ll make your skin crawl,” he said, and then, matching his comment, shuddered violently—which I didn’t in any way consider a consequence of his damp, clinging trousers—and when he’d controlled his shaking, finally went on, “but yes, we’ll surface there, right up Bgg’ha’s jacksy or as close as anybody would ever want to get to it. … !”

I waited until we were moving steadily forward again, in still water that came up just inches short of our knees, then said, “Henry, you say our skins will be made to crawl. But is there any special reason for that—or shouldn’t I ask?”

“You shouldn’t ask.” He shook his head.

“But I’m asking, anyway.” It was just natural curiosity on my part, I suppose. And whatever, I wanted Henry’s take on it; because we all see things, experience things, differently.

“Piccadilly Circus as was is lying crushed at the roots of Bgg’ha’s house. That great junction, once standing so close to the heart of a city, is now in the dark basement of the twisted tower, that vast heap of wreckage where he or it lords it over his minions—and over his human captive, his ‘cattle.’”

“His cattle … ” I mused, because that thought or simile was still reasonably new to me. At least I’d never heard it expressed that way before coming across Henry.

“As I may have told you before,” the old man said, “that’s all they are: food for Bgg’ha’s table, fodder for his stable.”

We were moving faster now, under an arched ceiling that was aglow, seemingly alive with luminous, swirling shoggoth exhaust. And the closer we drew to Henry’s goal or target, the more voluble he was becoming.

“Do you know why I’m here?” he suddenly burst out. “I think you do—or rather, you think you do!”

Nodding, I said: “But haven’t we already decided that? It’s revenge, isn’t it? For your wife?”

“For my whole family!” he corrected me. And the catch, that half-sob was back in his voice. “My poor wife, yes, of course—but also for my girls, my daughters! And my eldest, Janet—my God, how brave! I would never have suspected it of her, but she was braver than me. Inspiring, is how I’ve come to think of it; that my Janet was able to escape like that, and somehow managed to crawl back home again. But she did, she came home to me, and then … then she died! Not yet twenty years old, and gone like that.

“She died of horror, and of loathing—because of what had been done to her—but never of shame, for she’d fought it all the way. And it’s mainly because … because of what Janet told had happened to her that I’ve kept coming here. It’s why I’m here now: for Janet, yes, but also for her younger sister, Dawn, and for their mother; and for all the other females who’ve been taken and who are still there, maybe alive even now … in that twisted tower!”

“Still alive?” I repeated him. “You mean, maybe they’re not just fodder, after all?” At which I could have bitten through my tongue as it dawned on me that it was probably very cruel of me to keep questioning him like this. But too late for that now.

Sobbing openly and making no attempt to hide it, Henry replied: “Janet was taken two months ago. They took her in broad daylight—or what we used to call daylight—on her way back home from an SSR meeting. She’d been a member since the time her mother was taken. A boyfriend of hers from the old days saw it happen. It was those freakish flapping-rag things, those so-called Hounds. I was always telling her to stick to the shadows whenever she ventured out, but on this occasion I had forgotten to warn her against angles. They had taken her on a street corner, just ninety degrees of curb that cost her her freedom, and, as I’d believed at the time, her life, too. But no, Janet’s captors were working for that thing in the twisted tower, something I hadn’t known until she escaped and got home three weeks ago.

“That was when I found out about what goes on in that hellish place. Since then I’ve risked my own life five times making this trip in and out; always hoping I might see Janet’s mother, or her younger sister Dawn, and that I might be able to rescue them somehow … but at the same time making certain deliveries and planning for the future … in fact planning for right now, if you really want to know. But my wife … and Dawn, that poor kid, just seventeen years old: they’re somewhere in that nightmarish tower, I feel certain. But alive and suffering still, or dead and … and eaten! Who knows?” There he paused and made an attempt to get himself under control.

Feeling the need to have the old man continue, however—no matter how painful that had to be for him—I said, “Henry, before Janet escaped, did she ever see her mother, or her younger sister Dawn, there in the twisted tower?”

He shook his head. “Not once. Other girls—plenty of them—but never her Ma. And where Dawn’s concerned, that’s totally understandable. She was taken just three days after Janet found her way home in time to … time to die! In other words, she had been out of that place before Dawn was taken in.” He paused for a moment or two before continuing.

“Now I know it must sound like I’ve been pretty careless of my girls, but that’s not so. And maybe it’s best if they really are dead, because of what Janet … because of what she told me was happening to those … those other female captives.”

And as he broke down more yet, as gently as I could I asked him, “Well then, Henry, what did Janet tell you? What was happening in there, to the other female captives?”

Sobbing and stumbling along through the water—sobbing so loudly I thought he might sob his heart out—still he managed to reply: “Oh, that’s something I see in my blackest nightmare, Julian, and I see it every night! But first let me tell you how Dawn was taken …

“I left her at home while I went looking for a place to bury Janet. No big problem there … a hole in the ground, with plenty of bricks and rubble to fill it in. Then I went rummaging for food in the ruins of a corner store I’d found; canned fruits and meat and such. But when I got back home with my haul—‘home,’ hah!—a concrete cellar in a one-time museum; a wing of the old Victoria and Albert, it might have been. But anyway, when I got back, Dawn was gone and the place had been completely wrecked; what few goods we’d had—sticks of furniture and such—were broken up, strewn everywhere, and the place was damp and stank of … oh I don’t know, rotting fish, weeds, and stagnant water. The evil stench of the Deep Ones, yes, and they, too, are the loyal servitors of Bgg’ha, as I believe they are of all the octopus-heads … ”

And there Henry fell silent again, leaving only the echoes of his tortured voice, and the sloshing of our legs through the water. But I couldn’t let it rest at that. There were things he had told me for which I would like explanations.

“You said your wife was taken that first night, as all hell stampeded through the city and there was no defense against the turmoil, the horror. But that was a long time ago, Henry—even years! Weren’t these monsters slaughtering everyone and destroying everything in their path at that time? How could you possibly imagine your wife could still be alive in Bgg’ha’s twisted tower? Especially after what Janet told you about it?”

At which the old man seemed to freeze in his tracks, jerked to a standstill, and in the next moment turned on me, snarling: “How do you know what Janet did or didn’t tell me, eh? And how much do you know about that damned twisted tower? Tell me that, Julian Chalmers!”

Oh, I was glad in that moment that I had returned his suitcase to Henry, and that he was carrying it with both hands. He still had that gun on him, and if he could have reached for it without jeopardizing the safety of the case and its contents, I felt sure he would have done so. And who knows what he might have done then? But he couldn’t and didn’t, and I said:

“Henry, I don’t mean to hurt you, but the creatures in the tower … they eat people, don’t they? Haven’t you already said so? And it’s been a very long time for your wife. Now, don’t be offended, but in the light of your daughters’s ages, not to mention your own obvious years, it’s my understanding that your wife isn’t a mere girl; so what good would she be, alive, to such as Bgg’ha and his minions? I mean, him and his monsters? Beasts in their stables? What use to them except as … well except as—”

But that was as far as he would let me go, and I could tell by the look on his face that it wouldn’t in any case be necessary to finish my question.

“God damn you, Julian!” he said, as he turned away. “It was hope—desperate, impossible hope!—that’s all. And as for … for poor Dawn … ” But he couldn’t say on and so went staggering away through the sluggish, blackly glinting water, in the eerie light of the swirling shoggoth tissue.

I gave him a few moments before catching up, and said. “I’m sorry, Henry, but you leave me confused. I know you’re planning some kind of revenge—in whatever form that will take—but if you were really hoping that Dawn and your wife are still alive, mightn’t the violence of any such revenge hurt them, too, not to mention you yourself?”

Yet again he came to a halt and turned to me. “Of course it would, and will!” He said, “But far better that, a quick, clean death to them—to all of us!—than what they could be suffering; to what Dawn, if not her mother, must be suffering even as we speak!” And before I could say anything more: “Now listen:

“Did you know that they take young boys, too? Young men, I mean, your age or thereabouts? And since you appear to be good at figuring things out, can you guess what they are used for?”

“No, not really,” I said, unwilling to disturb him further. “But in any case maybe we should quiet it down now. I think I heard voices—some kind of sounds, anyway—from somewhere up ahead.”

The old man came to a halt, his eyes focusing as he looked all about, searching for signs on the old blackened walls. And: “Yes,” he whispered, about as quietly as I had suggested. “Your ears are obviously better than mine. We’re only five minutes or so away from Green Park, and that’s one of the worst places for—”

“—Deep Ones?” I finished it for him, but he only nodded.

And from then on we stayed silent, creeping like mice, glad that the water level had fallen away to no more than an inch or two. And for the second time Henry entrusted his case to me …

Ahead of us, the shoggoth light brightened up a little until it was about half as good as dim electric light used to be. But if it had been only half as bright again, that would have suited us just fine and still we wouldn’t have complained—no, not for a moment! And Henry was right: four or five minutes later, Green Park’s platform came into view.

By then those barking, gutturally grunting “voices” I had heard had faded into distant echoes before ceasing almost entirely. But still there were the sounds of some sort of laborious work going on in that subterranean burrow’s upper reaches. So we didn’t climb up onto the platform but splayed down on the tracks in the shadow of the bull-nosed wall, where we crouched down and kept the lowest possible profile as we traversed the mercifully short length of the station. But halfway across the comparatively open space, suddenly Henry paused to tug nervously on the sleeve of my parka, indicating that I should look at the platform’s flagged floor.

Still keeping low, but raising my head just enough to scan the length of the platform end to end, I saw what he had seen: the large, damp imprints of webbed feet where the dusty paving flags had been criss-crossed. Then, too, I detected the frowsy smell of weedy deeps and the half-human creatures that dwelled in them.

Deep Ones! Henry formed the words with his mouth and lips, both silently and needlessly. And: Look! He pointed.

From the mouths of the entry/exit archways, rubble had been cleared away and heaped to the side. The stairs and one wrecked elevator, visible beyond the arches, were also clear of debris; but from one such entrance a thin stream of water flowed forth, snaking across the platform and over the lip of the bull-noses, before finding its way down into the well and from there, presumably, into unseen channels that were deeper yet. But even in the moments we spent watching it, so the flow quickly increased to a torrent, and at the same time a massed, triumphant shout—a hooting, snorting uproar, even at the distance—sounded from above. But of course we already knew that the engineering going on up there wasn’t the work of entirely human beings …

And now Henry whispered, “Come, let’s get out of here!”

Minutes later, and a hundred yards or more into the comparative darkness of the tunnel, finally the old man spoke up again. “We were lucky back there. We’ve been incredibly fortunate!”

“Oh?” I replied. “Lucky? How come?”

He looked at me incredulously. “Why, the fact that they had recently gone up out of the station! And that they hadn’t begun to flood the place earlier, like yesterday maybe. For if they’d done that we’d the swimming by now! Surely you know or can guess what they were doing, what they’re doing even now?”

Trudging along beside him, sloshing through inches of cold, black water, I shrugged. “Well, like you said: they’re flooding the place.”

“Yes, but why?”

“Because … because they like the water?”

Henry offered up a derisive snort, and repeated me sarcastically: “‘Because they like the water’? Is that all? Man, can’t you see? Don’t you understand? They’re terraforming—no, aqua-forming—the Underground system, similar to what we were doing to Mars before those freaks in the Esoteric Order fucked everything up! They’re making the Underground suitable, comfortable, compatible—to themselves, to their loathsome way of life! Now do you see it? This maze, these endless miles of tunnels, stations, and levels; these massive great rabbit-holes—and all of them filled with water! Paradise to the Deep Ones! Subterranean Temples to their master, octopus-headed Bgg’ha, with submarine connections to his twisted tower like a great sunken cobweb!”

It was an awesome, even awe-inspiring, thought … the entire Underground system filled with water: a vast submarine city where the Deep Ones could spawn and worship their bloated black deity for as long as the Earth continued to roll in its orbit.

Then for several long minutes we remained silent, Henry and I, as we slopped along under the swirling and ever-brightening glow of shoggoth filth.

But eventually he said, “Well then, Julian, have you figured it out yet?”

“Eh? Figured what out?”

“Why they take young men, of course.”

“You mean, if not to eat them?”

“Yes,” he nodded. “If not to eat them. What other use could young men be put to, eh?”

Deciding to let him tell me, I shook my head. “I’ve no idea, Henry.”

And beginning to sob again, however quietly, he said, “It’s because young men are sexually potent, Julian. Just like horses in the stud farms, as once were in the old days. That’s what my girl Janet told me. But it’s also why she escaped and came home worn out, dying, and pregnant! The baby—not much more than a fetus, I imagine, poor innocent creature—he or she died with Janet.

But better that then … than the other. And now … and now … ”

I nodded and said, “I understand—I think. And now there’s Dawn. Why don’t you tell me about her, if you can?”

“No,” he shook his head, “you don’t understand! You haven’t thought it through. But I didn’t have to, because I had it from Janet, and I’ll tell you, anyway; or perhaps by now you can tell me? Why would a monstrous thing like Bgg’ha—and his monsters in that twisted tower of a ‘house’—why would they want children, babies, from their captives?”

We both slowly came to a halt and stood facing each other; but knowing what he was getting at I made no reply. The old man saw that I knew and nodded an affirmative. “Oh, yes, Julian. In the long ago era of sailing ships, men from the west would sometimes come across cannibal tribes in the South Sea islands, and these savage people had a term for the enemies they roasted for food. The called them—or the flesh they ate off them—‘long pig,’ because that’s how we taste, apparently. Now I don’t know if they ever tried ‘short pig,’ if you get my meaning, but what could be more tender or pure than—”

“—Yes, I do understand, Henry.” I cut him short. “There’s no need to torture yourself any further!”

“But what horrified me most,” he continued, as if he hadn’t heard me at all, “wasn’t the thought of those monsters at their repast, not but wondering what the young men who fathered those babies—what they themselves, or for that matter the mothers—could be living on in the twisted tower! For what other source of … food could there possibly be in that dreadful place? And what kind of inhuman, bestial people could bring themselves to do something as terrible as that?”

Henry could barely stifle his soul-wrenching sobbing as he turned away from me, staggering and yet seeming more determined than ever; windmilling his arms and only just managing to maintain his balance, as he went splashing along the drowned, rusty tracks.

I caught up with the old man, caught his arm to steady his before he could trip and hurt himself, and said, “There are all kinds of men, Henry. Most men couldn’t do that, I think, but as for those who can … what choice do they have? They could reap what they have sown, as it were—if in this case you’ll excuse such a metaphor—and eat or starve in the absence of any other choices, and that’s all. But you know, some men, women too, are very adaptable; and in desperate times and situations the survival instinct in people such as these will quickly surface, and they’ll soon become inured, accustomed to … to whatever. Yes, that kind of person can get used to almost anything.”

But yet again I don’t think he’d heard a single word that I had said. And instead of scolding me for my logical approach to what he’d told me—however sickening, disgusting that approach must have seemed to him, if indeed he had heard anything at all of it—he once again began to babble about his youngest daughter, Dawn:

“You’ve never seen a girl so lovely, Julian. Only thirteen years old when the world went to hell … growing up almost entirely underground, in that dark, damp basement we called home. What chance for poor Dawn, eh? … Never had a boyfriend, never knew a man … her dark-eyed, raven-haired beauty wasted in the gloom of a cellar. And all she ever saw of the outside world on those occasions, those very rare occasions, when, at her pleading, I would take her into the light of day, was the sullen sky and the shattered city … But we could never stay for long … not even crouching in the rubble … there were terrible things in the poisoned sky—the Shantaks, I’ve heard them called, and the faceless Gaunts—and it was never very long before they’d glide into view scouring the land as they searched … searched for … what else but us! … For mankind’s scattered remnants! … For what few human beings remained!

“But by Dawn … she was everything to me … as her mother before her, and her poor sister. But they were taken, all three … and what have I now—what’s left for me?—except the top of a measure … of some small measure … of revenge?”

It seemed to me the old man was waiting for an answer, and so I shrugged and obliged him, saying, “But it appears there’s nothing much left for you, Henry, except your small measure of revenge. So you’ll do what you have to—and for that matter, so will I.”

“So will you?”

I nodded and said, “Well, there’s nothing much left for me, either! So just like you, I’ll do what I have to … ” And I had to bite my tongue as I almost added, “to survive.”

The shoggoth light ahead of us was very much brighter now, and in order to change the subject I pointed it out to my companion. “Look there, it’s almost daylight up front! As daylight used to be, I mean.”

“I see it,” he answered, as his sobbing gradually subsided. “Another fifteen to twenty minutes and we’ll be there. Piccadilly Circus … or ground zero, if you prefer.”

“Hmm!” I said. “But I always thought that term described a point on the ground directly beneath the explosion—not above it.”

He was obviously surprised. “Quite right, yes. But since we both know what I meant, why nitpick?” Then, looking at me sideways and slyly, “By the way, you really have got it all figured out, haven’t you?”

“Most of it,” I nodded. “But I still don’t know, can’t see, how you’ve been able in the circumstances to build any kind of device powerful enough to make all of this worthwhile. I mean, you’d need a laboratory, and the know-how, and the materials.”

Henry returned my nod. “Very good,” he said, “Very clever. But don’t I remember saying that you had no idea who or what I am or was? I’m sure I do.”

“Ah!” I said. “So this is what you were getting at. Except you never did get around to telling me. So then, Henry, who and what were you?”

“I am, as you know, Henry Chattaway,” he replied. “But what you don’t know is that I have an almost entire alphabet of letters after my name, that I’ve twice been put forward as a candidate for a Nobel prize in physics, and that … ” For this was the one thing I had most wanted to know, but hadn’t dared to ask him outright in case it gave me away. And:

“Well, why shouldn’t I tell you?” he said, as the man-made cavern or excavation that was the main Piccadilly Circus Underground station gradually came into view up front. “For it’s too late now to do anything else but see it through: the last of my dreams come true on this long last night.”

And as we climbed up from the tracks onto the platform and I returned his small heavy suitcase to him, he continued: “Julian, I was the top man—or rather, not to make too much of it, one of them—on PFDP, the Plasma Fusion Drive Project. Similar in its way to the Manhattan Project, it was very hush-hush, even though no one in the scientific community gave it a snowflake’s chance in hell, even as a theory … what, abundant energy from next to nothing? You may recall that one hundred years ago the same dream had given birth to the bombs that put an abrupt end to the Second World War … not so much a dream as a nightmare, as it happened—at least until someone began speculating about the possible benefits: that perhaps nuclear power could provide cheap energy for the entire world, which, of course, never really worked out. The fuel was dirty, dangerous, and had safety problems; the mutations and fatal diseases that followed on inevitably from the errors and accident were hideous, while some of the infected radioactive regions remain hot even to this day.

“Well, history repeats, Julian. Plasma Fusion was the next best hope for cheap energy, far better and cheaper and so much easier to produce … why, men might even go to the stars with it—if it worked! But it didn’t, or rather it did, except even the smallest, most cautious of tests warned of a Pandora’s Box effect. Only let it loose, and it would initiate a chain reaction with anything it could touch and fuse with. That’s the only and best explanation I can give to a layman, especially in what little time we have left. But enough: we stopped working on it, and the world authorities—every single one of them who recognized the awesome power of this thing—signed up to a strictly monitored ban on any further experimentation … simply because they could not afford not to!”

While Henry talked, his voice gradually falling to a whisper, we had proceeded from the amazingly and relatively pristine platform to the stairs and elevator. The latter had not worked since the night of the invasion, of course not; but the stairs, completely free of rubble, had taken us eventually to the surface, which upon a time had been a landmark, a renowned open-air concourse where many streets joined in that great circus it was named for; a far different sort of circus now.

“This place,” I said, my normal voice echoing, “is looking rather empty. Not what one would expect, eh?”

“I know,” Henry agreed in a whisper, probably unable to understand why I wasn’t whispering, too. “It’s been like this each time. You would think it should be crawling, right? Which, in a way, it is. Not how you might expect—not crawling with alien life, no—but with the very meaning of the word alien itself!”

Crawling, yes. And making one’s skin crawl, too. Even mine. It was the way it looked, its shapes, angles; its architectural feature, if you could call them that. Non-Euclidan geometry.

It had four legs—or was it three? Maybe five?—all leaning inward, or was it outward? Something like the Eiffel Tower, but a twisted version, and what we’d surfaced into was the base of one such leg that had used to be Piccadilly Circus; the rest of them were green-misted with distance and aquatic, submarine-tinged shoggoth light and the intervening structures of anomalous buttresses, columns, and spiraling staircases. And nothing stood still but appeared literally to crawl, each surface flowing and changing shape of its own accord.

As for the staircases: some had steps as broad as landings, other with steps like frozen ripples on a pond, but rising, of course, and a third sort with no steps at all but smooth, corkscrew surfaces of glassy substance, sometimes turning on clockwise threads, and at other times winding in reverse. And all of them stationary, until one looked at them.

We were dwarfed, Henry and I, made minuscule by the gigantic scale of everything; and screwing up his face, shielding his eyes as he peered up into reaches that receded sickeningly into skyscraper heights and vast balconied levels, Henry said, “That must be where the life is: Bgg’ha’s throne room, cages to house his prisoners, dwelling areas for them that serve him. The monster himself will sit high above all that, dreaming his dreams, doing what he does, probably unaware that he’s any sort of monster at all! To him it’s how things are, that’s all.

“But as for his underlings—the flying things, Deep Ones, shoggoths that build and fashion for him, varnishing their work with slime that hardens to a glass as hard as steel—I have to believe that most of them … well, perhaps not the shoggoths—who are more like machines, however monstrous—that the majority of them, know full well what they’re about.”

I think you’re right,” I told him. “But you know, Henry, we’re not too small to be noticed. And I can’t imagine that we would be welcome here; certainly not you, suitcase and all! You need to be about your revenge, and should it work—to however small, or enormous effect—then, while you will have paid the ultimate price, at least your physicist friends in the SSR will surely be aware of your success and will carry on your work. So why are we waiting here? And why is that awesome weapon you’re carrying also waiting … to be put to its intended use?”

It was as if he had been asleep, or hypnotized by his alien surrounding, or maybe fully aware for the first time that this was it—the end of the long last night. For him, anyway—or so he thought. And he was right: it was the end of the road for him, but not as he thought.

“Yes,” he finally answered, straightening up and no longer whispering. “The others who helped me put it all together, they will surely know. They’ll see the result from the skeletal roof of the museum. When the explosion takes this leg out, the entire tower may rock a little … why, it could even topple! Bgg’ha’s house, brought crashing down on the city that he destroyed! And that, my friend, would be acceptable as a real and very genuine revenge! By no means an eye for an eye—for who has lost more than me?—but as much as I could hope for, certainly.”

“The roof of the museum?” I repeated him as he headed for a recess—outcrop, stanchion, corner or nook?—in the seemingly restless wall. “What, the Victoria and Albert, whose cellar was your home?”

“Eh?” He stared at me for long, hard moments … then shook his head. And: “No, no,” he said. “Not the Victoria and Albert, but the Science Museum next door, behind the great pile of rubble that used to be the Natural History Museum.”

“Ahh!” And at last I understood. “So that is where and how you and your team from the SSR built it, eh? You used materials and apparatus rescued from the ruins of the Science Museum, and you put it all together … where?”

“In the Museum’s basement,” he replied, as the wall seemed to enclose us in a leadenly glistening fold. “Those massive old buildings—and their cellars—were built to last. We had to work hard at it for a long time, but we turned the Science Museum’s basement into a workshop. After tonight, when they’ve seen the result of our work, they’ll make the next bomb much bigger; big enough to melt the entire city, what’s left of it … ”

And that was that. Now I had all that I needed from the old man, all that I’d been ordered to extract from him. Wherefore:

You can come for him now, I told the tower’s creatures—or certain of them—fully aware that the nearest ones would hear me, because they would sure as hell have been listening out for me. But meanwhile:

We had entered or been enveloped in a fold in the irrationally angled wall, a sort of priest’s hole in the flowing, alien cinder-block construction. And there in a corner—I’ll call it that, anyway, but in any case “a space”—was Chattaway’s device, its components contained in four more small suitcases, arranged in a sort of circle with a gap where a fifth (the one we’d been keeping from damage for this entire subterranean journey) would neatly fit. The cases were connected up with electrical cables, left loosely dangling in the gap where the fifth would complete the circuit; while a sixth component stood central on four short legs, looking much like the casing of a domed, cylindrical fire extinguisher. In series, obviously the cases had been a kind of trigger, while the cylinder—the bomb—would have contained anything but fire retardant! And affixed to the cylinder at its domed top, standing out vividly against the metal’s dull gleam, sat a bright red switch which, apart from the warning made manifest by its color, looked like nothing so much as an ordinary electrical light switch. The cylinder and its switch—a deadly, however inarticulate combination, as the bomb had recently been—told a story all their own, but one which was now a lie!

Quickly kneeling, Henry opened his case, reached inside and carefully uncoiled a pair of socketed cables which he connected up to the dangling cables on both sides. And now he was ready.

Screwing up his face and half-shuttering his eyes, I imagined in anticipation of pain, he reached over the wired-up suitcases, his trembling fingers outstretched toward the red switch … until, seeming to remember something, he paused and glanced at me. And then to my dismay, because I do have something of a conscience, after all, he said:

“I’m so sorry, Julian, but I did give you every opportunity to leave.”

“Yes, you did,” I replied, kneeling beside him and, before he could stop me, flipping open the lid of one of the suitcases. “But as you can see, I knew I really didn’t have to leave.”

His jaw fell; his mouth opened wide; he gurgled for several long seconds, and finally said: “Empty!”

“All of them,” I nodded. “Even or especially the cylinder—the bomb.”

But even then the truth hadn’t full sunk in, and he said: “I don’t understand. No one—nothing, not a single damned thing—ever saw me here. Not once!”

“Not here, no,” I replied with a shake of my head. “But you were seen leaving—just the once, by Deep Ones at Green Park—the last time you made a delivery. You were correct about their telepathy, Henry. Despite the confusion, the fear in your mind, they saw something of what you’d been up to, and Bgg’ha ordered a search made; otherwise no one or nothing might ever have come in here. Anyway, having discovered your secret, Bgg’ha wanted to know more about you … which is why I was send out to look for you. Or to hunt for you, if you prefer.”

Hearing that and finally, fully aware of the situation, the old man snapped upright. His eyes, however bloodshot, were narrowed now; the dazed expression was gone from his face; his gun was suddenly firm in his hand, its blued-steel muzzle rammed up hard under my chin. I thought he might shoot me there and then, and I wished that I’d called for them sooner.

“God damn!” Henry said. “But I should pay more attention to my instincts … I knew there was something wrong with you! But I won’t kill you here; I’ll kill you out there in the open—or what used to be the open—so that when you’re found with your face shot off, they’ll know there are still men in the world who aren’t afraid to fight! Now get moving, you treacherous bastard! Let’s get out of here.”

But as we moved from the drift and slide of the continually mutating wall to the even greater visual nightmare of the twisted tower’s leg’s interior, and when I was beginning to believe I could actually feel the old fellow’s finger tightening on the trigger, then I cried out: “Henry, listen! Do you really intend to waste a bullet on me? I mean, look at what’s coming, Henry … !”

They were shoggoths, two of them, under the direction of a solitary Deep One. They came into view apparently from nowhere, simply appearing from the suck and the trust to glide towards us. Or at least the shoggoths approached us, while the Deep One held back and kept his watery great eyes on his charges, making sure they carried out their instruction—whatever those might be—to the letter. And, of course, I knew exactly what they had been ordered to do.

Suddenly gibbering, Henry released me and turned his automatic on the twin pillars of blackly-tossing, undulating filth, slime and alien jelly as each advancing creature formed a half-dozen huge, slithering, soulless and half-vacant eyes in addition to the many it already had, and flowed upon him from both sides. He fired: once, twice, three times … until his hammer clicked metallically on a dead round, and hollowly on an empty chamber; then cursed and hurled the useless automatic directly into the tarry protoplasm of one of the awesome ten-foot monsters. And finally, as if he noticed for the first time just how close the shoggoths were, he turned and made to run or stagger away from … but too late!

Moving with scarcely believable speed, they were upon him; they towered over him to left and right, putting out ropy pseudopods to trap Henry’s spindly arms. And closing in on his desperately thin vibrating body, slowly but surely they melted him into themselves, burning him as fuel for the biological engines which they were.

Then, as his agonized shrieking tapered and died along with Henry himself, and as the smoke and gushing steam of his catabolism went spiraling up from the feeding creatures, the loathsome foetor of Henry Chattaway’s demise was almost as sickening as the live smell of his executioners; but in combination, overwhelming the already rancid air to burn like acid in my nostrils, even though I had moved well away, the two taints together were far more than twice as nauseating. And I was glad that it was finally over, for my sake if not for the old man’s …

In backing away from all this, I had come up against a different kind of body with a smell I could at least tolerate; indeed I even appreciated it. The shoggoth-herder looked at me rather curiously for a moment, his almost chinless face turned a little on one side. But then as he sniffed at me and finally recognized my Innsmouth heritage, my ancestry, he further acknowledged my role in these matters by turning away from me and once more taking command of the shoggoths.

Left to my own devices, I shrugged off a regretful, perhaps vaguely guilty feeling and set about climbing the stairway with the tall landing-wide treads. This was hard work, indeed, for I was already weary from my journey through the Underground with old man Chattaway and his suitcase full of useless batteries.

But up there, high overhead, I knew the ovens would also be hard at work. And long or short pig … what difference did it make if I was hungry? Didn’t men eat fish, and in France frogs, too? But I suppose that’s the trouble with changelings like me, changelings who—waiting for their change, when at last they, too, can go to the water—hunt human: sooner or later we’ll begin to sympathize, even empathize with the hunted.

However, and despite the greater effort, I soon began to climb faster. For also up there were the cages and other habitats … and at least one beautiful girl in her middle teens; a girl called Dawn, who had never known a man; or not until comparatively recently, anyway. A shame that there were others like me up there, but I expected that she would still be very fresh.