Читать книгу Nagasaki - Éric Faye - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

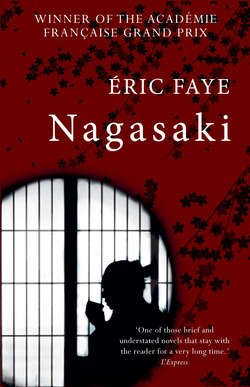

Nagasaki

ОглавлениеImagine a man in his fifties disappointed to have reached middle age so quickly and utterly, residing in his modest house in a suburb of Nagasaki with very steep streets. Picture these snakes of soft asphalt slithering up the hillsides until they reach the point where all the urban scum of corrugated iron, tarpaulins, tiles and God knows what else peters out beside a wall of straggly, crooked bamboo. That is where I live. Who am I? Without wishing to overstate matters, I don’t amount to much. As a single man, I cultivate certain habits which keep me out of trouble and allow me to tell myself I have at least some redeeming features.

One of these habits is avoiding as far as possible going out for a drink with my colleagues after work. I like to have time to myself at home before eating dinner at a reasonable hour: never later than 6.30 p.m. If I were married, I don’t suppose I would stick to such a rigid routine, and would probably go out with them more often, but I’m not (married, that is). I’m fifty-six, by the way.

That day, I was feeling a little under the weather, so I came home earlier than usual. It must have been before five when the tram dropped me in my road with a shopping bag over each arm. I rarely get back so early during the week, and as I went inside I felt almost as if I was trespassing. That’s putting it a bit strongly, and yet … Until quite recently, I hardly ever locked the door when I went out; ours is a safe area and several of my old-lady neighbours (Mrs Ota, Mrs Abe and some others a bit further away) are at home most of the time. On days when I have a lot to carry, it’s handy if the door is unlocked: all I have to do is get off the tram, walk a few steps, pull the sliding door across, and I’m inside. I just take off my shoes, put on my slippers and I’m ready to put the shopping away. Afterwards, I usually sit down and draw breath, but I didn’t have that luxury this time: at the sight of the fridge, the previous day’s concerns came flooding back to me all at once.

When I opened it, however, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Everything was in the right place, which is to say the place I had left it that morning. The pickled vegetables, cubes of tofu, the eels set aside for dinner. I carefully inspected each glass shelf. Soy sauce and radishes, dried kelp and red-bean paste, raw octopus in a Tupperware container. On the bottom shelf, all four triangular pouches of seaweed rice were present and correct. The two aubergines were there as well. I felt a weight lifting from me, especially since I was convinced the ruler would provide extra assurance. It’s a stainless-steel one, forty centimetres long. I stuck a strip of blank paper to the unmarked side and plunged it into a carton of fruit juice (with added vitamins A, C and E) that I had opened that morning. I waited a few seconds, just long enough for my probe to soak up the liquid, and then I slowly pulled it out. I hardly dared look. Eight centimetres, I read. Only eight centimetres of juice remained, compared to fifteen when I had left for work. Someone had been helping themselves to it. And yet I live alone.

My fears boiled up again. To make absolutely sure, I checked the notebook where I had been recording levels and quantities for several days. Yes, it had definitely been fifteen that morning. Once I had even gone as far as taking a photograph of the inside of the fridge, but had never done it since. Either I couldn’t be bothered or had felt stupid. That was in the days before I knew for sure; any remaining doubts had now vanished. I had new evidence that something really was going on, the third such sign in the last fortnight, and bear in mind I’m a very rational person, not someone who would believe a ghost was popping in to quench his thirst and polish off the leftovers.

My suspicions had first been aroused several weeks earlier, but had rapidly disappeared. Yet some time later they came back in a vague sort of way, rather like midges that buzz around in the evening air and then fly off before you’ve quite registered they’re there. The whole thing began one day when I was certain I had bought some food that I then couldn’t find. My instinctive reaction was, naturally, to doubt myself. It’s so easy to convince yourself you put something in your shopping trolley when in fact you only meant to. It’s so tempting to put memory lapses down to tiredness. Tiredness is used as an excuse for almost anything!

The second time, by chance, I had kept the till receipt and was able to confirm I had not imagined it: I really had bought the fish that had since vanished into thin air. This didn’t make things any clearer though; I remained mystified and no closer to an explanation. I was rattled. The inside of my fridge was, in a sense, the ever-changing source of my future: the molecules that would provide me with energy in the coming days were contained within it in the form of aubergines, mango juice and whatever else. Tomorrow’s microbes, toxins and proteins awaited me in that cold antechamber, and the thought of a stranger’s hand taking from it at random and putting my future self in jeopardy shook me to the core. Worse: it repulsed me. It was nothing short of a kind of violation.

The night did nothing to dispel my unease over the disappearing fruit juice. In the morning, I set my nit-picking mind to piecing together the puzzle. At times like this the brain investigates, reconstructs, corroborates, deduces, unpicks, juxtaposes, supposes, calculates, suspects. I ended up cursing that grey Sanyo fridge with the slogan ‘Always with you’ slyly printed across it. Was there such a thing as a haunted refrigerator? Or one that fed itself by skimming off part of its contents? When I got back from work, I was eager to do something to calm my anxiety, which was slowly becoming a form of torture. At just gone six o’clock, there was still time … It was a last resort and I would probably feel ridiculous doing it, but my stress levels were now such that I simply had to know. To hell with the routine, I would eat dinner late.

I put my coat and shoes back on, went out, and caught a tram heading down towards Hamanomachi. The shop where I intended to purchase my new ‘trap’ was only two stops away and, providing my DIY skills were up to the task, I would sleep more peacefully afterwards.

In fact I didn’t need to put my handyman credentials to the test, as the device turned out to be much easier to fit than I had anticipated. I would have to wait until I was at work the next day to put my plan into action, a strategy that would make my fridge readings look like Stone Age techniques. I would aim to get in as early as possible and be at my desk by 8 a.m. I was relieved to be taking action but impatient to get started and, to tell the truth, beginning to lose the plot: it was after nine when I realised I hadn’t had a bite to eat. Oh well, just this once.

Sitting in my armchair with a pot of hot tea beside me, I tried to take my mind off things by watching TV, but nothing gripped my attention. Instead I picked up the magazine I subscribe to but never normally read. On page 37, a picture of a horribly wrinkled man caught my eye. ‘Tanabe Tomoji hasn’t touched a drop of alcohol in his life,’ declared the journalist. As I skimmed the article, I couldn’t help thinking what a fool this man was. Tanabe, the oldest man alive, maintained he had got to the age of 113 eating nothing but vegetables and the occasional deep-fried prawn as a treat. Well, he sounded like a real live wire. This living fossil’s last remaining source of pleasure consisted of peeling a prawn or two, though he was eating fewer and fewer of them because greasy foods no longer agreed with him. Poor old Tanabe! Soon you’ll be welcomed into nirvana and everything will be all right, you’ll see: they’ve put a fried-prawn stand right by the entrance and you can stuff yourself to your heart’s content without worrying about the oil.

It seems ridiculous now, but at the time I was captivated; I stopped thinking about my trap and read the article from beginning to end. ‘I’m happy,’ the old fogey told them. ‘I want to live another ten years.’ Silly twerp! And I don’t know why but afterwards, oblivious to the sun going down amid the far-off rumble of traffic, I stayed for some time sitting in the dark, looking out of the bay window but not seeing the bay itself, the looming ships or the dockyard.

At that point in the evening you assume that your waking self with all its sediment of bitterness, worries, regrets or remorse and jealousy, will dissolve in a deep sleep, until the night veers off course. Though no different from usual – no louder, no quieter – the cicadas wake you the second you start drifting off. They screech on and on, driving you to distraction like drunken harpies; or are you being over-sensitive tonight? Here they come, single file into your head through one ear and out the other, circling around your skull before diving in again, spiralling malevolently in their line, laughing mockingly. Mercifully a violent downpour disperses them before dawn like the protesters on the NHK news last night, driven from wherever it was by water cannons. But how can you doze off knowing that with a simple copy of the key, the intruder – since there obviously is one – can let themselves into your home at any moment, together with a gang of heavies to beat you up and leave you for dead before you even know what’s happening to you? You think to yourself: it’s because of you, intruder, that I can’t sleep, and I’ll have a terrible headache later sitting in front of my areas of high and low pressure, but just you wait. You’ll get what’s coming to you. Everything is in place. And look, it’s time to get up; it’s already six thirty.

There comes a time when nothing happens any more. The ribbon of destiny, stretched too wide, has snapped. There’s no more. The shockwave caused by your birth is far, oh so far, behind you now. That is modern life. Your existence spans the distance between failure and success. Between frost and the rising of sap. I had been mulling all this over on the tram the previous week, and that morning, as I sat in the same spot on the tram, looking out at the same urban wallpaper, the thought that it might not be set in stone made me euphoric. The vehicle hurtled along, taking in the stops, taking in pensive, silent humans preoccupied with trying to decipher unfathomable dreams. Maybe they lived more fully in their sleep than in their waking hours? After a litany of stations I knew by heart – Kankodori, Edomachi and Ohato, Gotomachi followed by Yachiyomachi then Takaramachi – I got off and changed onto another line. Sometimes I finish my journey on foot, but this morning I wasn’t up to it, and besides I was in a hurry. No sooner had I left the metallic grating sound of the tram behind me than the cicadas took over, screeching as I walked under their trees. They were judging me, confounding my thoughts and barely formed sentences so that as soon as I reached the office I shut the windows and asked my colleagues to give me a moment: I was up all night because of them and they’re hysterical this morning, listen to them; it makes you want to block your ears, and even then, when everything’s sealed up, they still find a way in; they can get through glass and concrete, they pass through walls, these creatures – which brought my mind back to the matter in hand: the camera, and my very own person who walks through walls.

I retreated to my desk, alone. As far as my colleagues knew, I was busy studying the overnight satellite photos; because, like them, I am a meteorologist. Once I’ve logged on to my computer and launched the relevant programs, I spend each morning consulting the latest charts and reports sent in from various weather stations. Since on this occasion there was no need to issue any weather warnings or attend to any other urgent tasks, I opened a window in the bottom right-hand corner of my screen. In the space of a few clicks, I had set the trap. It was done. As if by magic, a still shot of a kitchen appeared, the same kitchen where I had just been eating my breakfast. Everything looked calm. If I had been married with a wife at home, I could have watched her moving about from my desk. Before leaving the office of an evening, I would know what she was making for dinner. The webcam I had installed the previous day worked brilliantly. Without leaving my seat, I could be an invisible, weightless ninja spying on my own home. I had achieved ubiquity without even trying. But then the telephone rang, telling me I was needed. The departmental meeting scheduled for ten o’clock had been brought forward and was starting any minute. Blast, just as I was trying to concentrate on the little aquarium in the bottom right-hand corner of my screen.

Later on, once the meeting had finished, I resumed my watch, regaining the use of my third eye. It’s possible to link these tiny webcams to your mobile phone, which is exactly what I should have done had mine not been prehistoric (three years old). Then I wouldn’t have had to waste my time during the meeting; I could have carried on watching the house while listening to them listening to each other, repeating each other, rehashing each other. If I was married, I could keep an eye on my wife, either out of jealousy or because I couldn’t bear to be parted from her. Passing in front of the camera, she would wink flirtatiously at my third eye, perhaps even blow it a kiss. Come the afternoon, I would know which friends she had round and what they were wearing. But today, the camera was far from being a chastity belt or any other marital tie. From inside the glass cabinet where I had installed it, the camera unveiled a chilling picture of my solitude which made me shiver if I dwelt on it. Luckily I had no time to dwell on it because the telephone rang, a colleague asking my advice, and I fine-tuned the shipping forecast: my job consists of pre-emptively saving the lives of fishermen from Tsushima-to to Tanega-shima and beyond.

As the morning wore on, so the cicadas kept up their racket. I was at their mercy, my nerves in tatters. They could force a confession from any suspect.

The house, on the other hand, was still giving nothing away.

I maximised the window in the bottom right-hand corner. There it was, full screen. A full screen of nothing. There was something odd though. Now that I had blown it up and could see the kitchen in detail, something was niggling me. Was it the bottle of mineral water left out on the work surface? Experts have been known to rely on such intuitions: the painting in front of them is a fake; they are utterly convinced of it, even without proof. They step right back and then lean in closer, in much the same way as I was inspecting the kitchen under the magnifying glass of my fears. This tableau was a fake. The bottle had moved. While I was a) in the meeting, b) in the loo, c) on the phone or d) sidetracked by a colleague struggling to interpret a shot. Was I really, totally sure that it wasn’t exactly where I had left it? For the remainder of the morning, I left my desk only to go and buy a bento box from the local Lawson, which I grazed on in front of my computer: an absence of ten minutes that I was now compensating for by not taking my eyes off the table where I would have dinner that evening. There I was, like a weatherman under house arrest in the eye of a static anticyclone. As I opened the box which held my lunch, I had the impression of looking into a doll’s house from above, with all the little neatly divided compartments filled with multicoloured items of food. And I said to myself, you could fit a webcam in each of your six rooms, split the screen into the same number of windows and do nothing from morning to night but examine from a distance the bento box you live in.

And then it was lunch time. My colleagues deserted the open-plan office, the air conditioning having given up the ghost, and, preferring to swelter rather than put up with the cicadas, I went round shutting all the windows again, leaving just one open, the one on my computer screen, which I continued to watch while finishing the contents of the box compartment by compartment. Hadn’t the bottle of water been slightly closer to the sink earlier on? A matter of fifteen or twenty centimetres, it seemed to me. No sooner had I convinced myself of this than I changed my mind again. You’re making things up, trying to rationalise your unconscious thoughts. For that matter, are you really sure those yogurts disappeared after all? You should report it, you know, go to the police: I’ve had three pots of yogurt stolen in the last few months. Come on now, calm down. Lately, you’ve been all on edge.

That afternoon, I was talking to two new recruits who couldn’t find anything better to do than pester me. While I was explaining how to use a program to design maps, I felt like banging their heads together to make them see they could not have picked a worse time to bother me. It must have been obvious from my curt tone, especially when one of them asked what the webcam at the bottom of the screen was for, there. I dodged the question, continuing to give explanations while all the time keeping half an eye on the kitchen. They must have thought I had OCD, or taken me for a home-loving depressive. Or was it his elderly mother’s house he was watching from afar? I was about to comment on something when the rectangle in the bottom right darkened slightly. A figure was moving about on screen, shrunken (the wide-angle camera flattened everything in its field; I shouldn’t have mounted it so high) and silhouetted; for a few seconds, the window that looks out onto the road was partially eclipsed. As I carried on talking to the two men next to me, I gradually realised the person I was dealing with was a woman and, judging by her hairstyle and slight frame, no longer a girl by any stretch of the imagination. She simply crossed the room and, since her head was turned the other way, I saw nothing of her face but the outline of her cheek; I couldn’t make out any distinguishing features at all. Anxious not to let them sense my unease, I turned back to the two nuisances and made trivial chit-chat, trying my best to sound casual. That was a mistake. By the time I turned my attention back to her, the figure had moved out of frame. My two colleagues thanked me and left me to my empty kitchen; it was as if I had been fooled by a hallucination. She was bound to come back the other way; I just had to be patient.

Only she didn’t. Ten minutes, a quarter of an hour went by. It would have been ridiculous to call the police; what exactly would I have reported? The disappearance of a shadow? I could just hear the policeman muttering as he searched the house: perhaps you’re married in a parallel dimension, Shimura-san, or maybe you thought you had at last seen the girl you would have liked to marry? (Then, leaning towards me, acting the shrink.) A girl you knew as a teenager, who turned you down just like the others? Whose arrogant features have stayed with you, lodged deep in your mind, and now that vivid memory is messing up your brain. Unless it’s a fairytale elf that’s moved in? We’re all like you, Mr Shimura, we all have our own elves to help us through the day. Then, speaking in hushed, nudge-nudge tones and shooting me a lewd smile, he would lay out his little theory: a prostitute or a junkie, wasn’t she, go on, admit it, or a girl from a massage parlour you fell for and then tired of – these things happen, we’re only human – and she clung to you because she had nowhere else to go, so you decided to get her out of your hair by claiming trespass, burglary …

No! I didn’t want to hear any nonsense like that. I needed proof. Police officers don’t go around arresting thin air. I temporarily closed the kitchen window on my screen. My colleagues reopened those of the office and the cicadas burst in by the dozen. Filthy creatures. Behind them, the crows endlessly repeated the same caaw, caaw sound. And in the wings of this choir were the soloists, the bells of Urakami and the sirens of police cars chasing elves.

The cicadas were still tormenting me when I got off the tram, harpies unleashed on me, shaking their maracas in my ears. Invisibly imposing their rhythm on my walk towards insanity. I felt afraid at the thought of entering my house. From a distance, the lock did not appear to have been broken. Whether that was reassuring or not, I didn’t know. Old Mrs Ota, keeping watch as always, saw me standing rooted to the pavement and called me over. She does this from time to time, motions me over and we chat about one thing or another. She once told me I reminded her of her son. Same generation, same grown-up schoolboy charm, but he has a family and lives a long way away, and only visits once a year. Or twice if I should happen to die, she joked.

Still preoccupied by the events of the afternoon, I half expected her to declare theatrically, as she does when recounting local gossip, ‘I saw her coming out of your house!’ But no, she only wanted to natter about this and that, and in the end it was me who asked the question. From the way she raised her eyebrows, I could see she hadn’t noticed anything out of the ordinary and was almost annoyed with herself: but I haven’t moved an inch all day except to do my morning shop. Did that mean I had dreamed the figure on my screen? Did a webcam eventually progress from scanning Formica kitchen surfaces to capturing the resident spirits, or kami, too? Did they record the spectres coming and going in a place thought to be empty? Over time, might the ‘retina’ of a camera become sensitised to what the human eye cannot perceive, the way a dog picks up ultrasound waves that his master’s ears are incapable of hearing? As I made to leave, Mrs Ota threw me an oblique glance. Why do you ask? Should I have seen someone? Did you have a visitor? I assumed an air of unease, sighed softly and smiled.

‘I must be becoming suspicious in my old age. There’s a woman who used to clean for me, who I think kept a set of my keys. I saw her hanging around here this morning. So …’

‘We’re quick to suspect the worst.’

‘Well, in this day and age.’

‘I don’t remember you having a cleaning lady, Shimura-san.’

‘Oh, it wasn’t for long.’

‘You didn’t trust her?’

I didn’t reply. Without explicitly asking, I had given her reason to keep an even closer eye on things over the coming days. What deity would demand offerings of yogurt, a single pickled plum or some seaweed rice? Never mind that I was raised a Catholic, I often go to feed our kami at the local shrine, but it never occurred to me for one moment they would come into people’s houses and help themselves.

‘I think I’ve seen her, you know, your cleaning lady. It must have been about a month ago – I saw someone in your kitchen in the middle of the day. I said to myself, now that’s odd, but then I remembered that you had a sister who comes to visit sometimes. Or perhaps he’s got a girlfriend, I said to myself as well. Perhaps he’s got a girlfriend.’

Her chubby face wore a look of pure kindness. Mrs Ota clearly meant well, but I dismissed her suggestion with an awkward laugh designed to hide my embarrassment.

‘I thought … Time’s ticking on, Mr Shimura. None of us are getting any younger! You should have a girlfriend, or you’ll end up spending your old age on your own.’

After sliding the door open, I listened out for any strange noises. I had never felt this way before. Either old Mrs Ota had stopped paying attention at some point that afternoon, or the figure I had glimpsed had stolen away through a back window, sneaking out unnoticed like a ninja that just materialises and then vanishes in the same way, suddenly and soundlessly. I quickly went round inspecting the windows and noticed that one of them, in the guestroom, was unlocked. Yes, she could easily have slipped out of this room: it didn’t back on to anything, no Mrs Ota on this side. Only the hills opposite, bristling with grey roofs that always make me think of a monster’s scales. And this monster was falling asleep. I fastened the lock and swore to check the windows every morning before leaving the house. I felt better after closing the blinds, if still slightly on edge. I was thinking about the figure Mrs Ota had caught sight of the previous month.