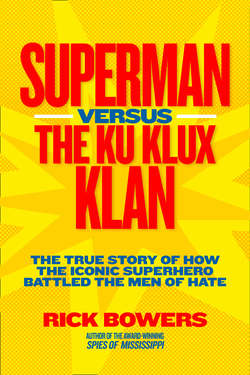

Читать книгу Superman versus the Ku Klux Klan: The True Story of How the Iconic Superhero Battled the Men of Hate - Richard Bowers - Страница 9

* CHAPTER 1 * KOSHER DELIS & DISTANT GALAXIES

ОглавлениеWALKING DOWN THE HALLWAY of Glenville High, Jerry Siegel braced for another day of disappointment. It was only 8:30 in the morning, and the 17-year-old science fiction aficionado was already counting the hours to the final bell. The pretty girl with the long, brown hair and flashing eyes would no doubt turn away from his glances. The student editor of the award-winning school newspaper, the Torch, would probably reject his latest story idea. The swaggering guys on the football team and the cliquish cheerleaders on their arms would not even acknowledge his existence. At least after school Jerry could hustle to his house at 10622 Kimberly Avenue, bound up to his hideaway in the attic, pick up a science fiction magazine, and lose himself in a fantasy world of mad scientists and rampaging monsters, space explorers and alien invaders, time travelers and spectral beings.

Jerry loved science fiction. Ever since he was a kid he had buried himself in a new breed of magazines with titles like Weird Tales and Amazing Stories. Full of dense print and crude illustrations, these simple, low-budget publications were magic to him. The smudged type on that thin paper told stories of intergalactic warfare, futuristic civilizations, and brilliant new technologies that promised a brighter and better world.

These astounding tales were attracting a growing audience of teenage fans across the country. They referred to their magazines as zines and shared their reactions and ideas through the mail. For Jerry, zines were the ultimate escape from his humdrum existence at school and the tension at home with his mother, who constantly babied him and worried that he was too much of a dreamer to make it in a harsh world.

Jerry had to admit that his future did not look all that bright. Because he lacked the grades and the money to go to college, the world ahead often seemed as bleak as the coldest, darkest reaches of outer space.

Jerry Siegel was the youngest of six children born to Mitchell and Sarah Siegel. Like so many other Jewish immigrants, Mitchell and Sarah had fled persecution in Europe to build a new life in America. After arriving from Lithuania, the couple had changed their name from Segalovich to fit in more easily in their adopted homeland. At first Mitchell worked as a sign painter and dreamed of becoming an artist. But with a growing family to support, jobs scarce, and money tight, he gave up his dream of painting beautiful works of art. Instead he opened a haberdashery, or secondhand-clothing store, near the factories in the old Jewish ghetto of Cleveland. Mitchell worked long hours, saved his money, and eventually moved the family out of the ghetto and into a comfortable, three-story, wood-frame house in Glenville, a close-knit neighborhood of nice homes, spacious front porches, and big backyards. Set amid rambling green hills and gurgling streams that meandered to Lake Erie, Glenville was the American dream come true for its tens of thousands of Jewish residents.

Glenville was also a protective cocoon for those residents—a safe haven from the prejudice that lurked just outside its borders. Sure, there were plenty of good, hardworking Christian people out there, but some Christians called Jews insulting names like kike and hebe and instructed their children to stay away from those kinds of kids. The classifieds in the Cleveland Plain Dealer were filled with job ads bluntly stating “No Jews Need Apply.” Country clubs in exclusive neighborhoods refused to accept Jewish members. There were even hate groups that called for the kinds of mass-removal programs that the Siegels thought they had escaped when they left Europe. In fact, Jews could simply turn on their radios to hear the Radio Priest, Father Charles Coughlin, spew anti-Semitic tirades from the National Shrine of the Little Flower Parish in Royal Oak, Michigan, just 180 miles from Glenville. A frequent speaker at mass rallies in Cleveland, Coughlin organized his most loyal followers into Christian Front organizations to oppose equality for Jewish Americans.

As the Great Depression wreaked economic havoc on the nation, another frightening fringe organization was becoming more and more active. With unemployment at a record high and clashes between striking workers and employers turning into bloody melees, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) sought to exploit public fear. Preaching a gospel of racism and religious intolerance, the KKK called upon white protestant men to band together to fight the Jew’s demand for social acceptance, the Negro’s plea for just treatment, and the immigrant’s call for decent jobs and fair pay. To keep up with the times, this secret society of hooded vigilantes had expanded its traditional hate list from Negroes, Jews, and Catholics to include union organizers, liberal politicians, civil rights advocates, crusading journalists, and supporters of the New Deal—President Franklin Roosevelt’s program to restore the economy by putting people to work. As tensions rose, new recruits came forward to join the nation’s most militant defender of white protestant rule. Although the KKK recruited only members who were white and protestant, it boasted of standing for the principle of “100 percent Americanism.”

On summer days the streets of Glenville buzzed with kids riding bikes, skipping rope, and playing stickball or hide-and-seek. On summer evenings teenage boys and girls walked hand in hand down the sidewalks, and gaggles of kids hung out on spacious front porches, told jokes, flirted, and talked about the future. Throughout the week pedestrians flowed down lively East 105th Street, where Solomon’s Delicatessen piled corned beef and pastrami high on fresh rye bread and Old World restaurants served classic European fare like brisket, cheese blintzes, matzo ball soup, and lox and bagels. On Saturdays, worshippers flocked to more than 25 synagogues, the men wearing the traditional yarmulke to cover their heads and the women dressed in the fashions of the day. The jewel of Glenville was the grand Jewish Center of Anshe Emeth (a synagogue) at East 105th and Grantwood Avenue, a modern building with a sculpture of the Star of David crowning its roof. It was the central gathering place for the community—the place to go to shoot basketball, to swim laps, or to take classes on subjects ranging from Hebrew tradition to American culture. By the early 1930s more than half of Cleveland’s Jewish population lived in Glenville, and more than 80 percent of the 1,600 kids at Glenville High were Jewish.

JERRY SIEGEL WAS DIFFERENT from most of the other kids in Glenville. While they were playing ball in the street, shooting hoops at the community center, or shopping on 105th Street, Jerry was holed up in the attic with his precious zines. He also loved to take in the movies at the Crown Theater, just a couple blocks from his house, or at the red-carpeted and balconied Uptown Theatre farther up 105th. Scrunched in his seat with a sack of popcorn in his lap and his eyes fixed on the screen, he marveled as the dashing actor Douglas Fairbanks donned a black cape and mask to become the leaping, lunging, sword-wielding Zorro. Jerry admired Fairbanks and all the other leading men—those strong, fearless, valiant he-man characters who took care of the bad guys and took care of the gorgeous women too. Jerry worshipped Clark Gable and Kent Taylor, whose names he would later combine to form Clark Kent.

Jerry usually sat in darkened theaters alone as he absorbed stories, tracked dialogue, and marveled at the characters. After the movies he would walk to the newsstands on St. Claire Avenue to pick up a pulp-fiction novel or a zine. Soaking in every line of narrative and dialogue, he would read the books and magazines cover to cover—then read them again. Turning to his secondhand typewriter, he would dash off letters to the editors, critiquing the stories and suggesting themes for future editions. He would scour the classified sections for the names and addresses of other science fiction fans and send them letters in which he shared his ideas for stories, plots, and characters. For kids like Jerry, science fiction provided a community—a network of fans bound together by a common passion.

One of Jerry’s favorite books was Philip Wylie’s Gladiator. Initially published in 1930, it was the first science fiction novel to introduce a character with superhuman powers. Jerry moved through the swollen river of words like an Olympian swimmer, devouring the description of the protagonist, Hugo Danner, whose bones and skin were so dense that he was more like steel than flesh, with the strength to hurl giant boulders, the speed to outrun trains, and the leaping ability of a grasshopper. Danner’s life is a tortured pursuit of the question of whether to use his powers for good or evil. That made Jerry think about how hard it was to choose right over wrong.

Then there was that unforgettable image of the flying man—the one he had seen on the cover of Amazing Stories. Jerry would hang on to that image for the rest of his life. The flying man, clad in a tight red outfit and wearing a leather pilot’s helmet, soared through the sunny sky and smiled down on a futuristic village filled with technological marvels. From the ground, a pretty, smiling girl waved a handkerchief at the airborne man and marveled at his fantastic abilities. In this edition of Amazing Stories Jerry saw a thrilling new world of scientific advances and social harmony—a perfect green and sunny utopia to be ushered in by creative geniuses with more brains than brawn, more natural imagination than school-injected facts, more good ideas than good looks. Jerry wanted to help create that utopia. Luckily, he had a partner in his quest.