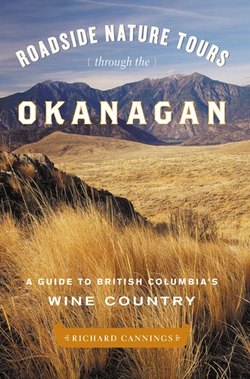

Читать книгу Roadside Nature Tours through the Okanagan - Richard Cannings - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTUCKED INTO THE EASTERN flanks of the Cascade Mountains is a narrow valley unlike any other in Canada—the Okanagan. This small watershed is only 30 to 60 kilometres wide and extends 170 kilometres from Osoyoos in the south to Armstrong in the north. The Okanagan has a dry climate but is filled with a series of large lakes that moderate the hot days of summer and the Arctic airflows of winter. The lakes and small streams of the valley also provide water that has transformed most of the desert grasslands in the valley bottom into lush orchards and vineyards. And packed into this valley are some of the rarest and most fascinating plants and animals in the country.

When I was young, my hometown, Penticton, used to advertise itself as the “City of Peaches and Beaches.” In fact, a concession stand in the shape of a giant peach still sits on the shore of Okanagan Lake. In those days visitors came to the Okanagan Valley for just that combination—a week or two with the family to lie on glorious natural sand under the hot sun, followed by a quick stop at the fruit stands on the way home to Vancouver or Calgary to stock up on cherries, apricots, peaches, and apples.

Although I grew up on an apple orchard and spent perhaps too many of my boyhood summer days on the sunny lakeshore, I always knew the Okanagan was much more than peaches and beaches. Our family often hosted keen birders and young biologists who came to enjoy the valley’s other riches—an incredible diversity of plants and animals, many of which were difficult to find anywhere else in Canada. I quickly developed a strong sense of pride about how special this place was and have carried that feeling ever since.

After living in the urban excitement of Vancouver for more than twenty years, I was drawn back to the Okanagan in 1995 by my deep love for the region. Things had changed, of course— twice as many people lived in Penticton than when I last lived there, and five times as many in Kelowna. But I also got the feeling that more local residents shared my feelings about the natural Okanagan and that more tourists were coming just to see spring wildflowers and listen to birdsong, to climb the rugged cliffs along Skaha Lake, and to cycle along the historic and spectacular Kettle Valley Rail Trail. Shortly after I settled in, I got a phone call from the local chamber of commerce suggesting that we form a group to organize an annual nature festival, an event that would have been unthinkable when I was a child.

I also noticed that the agriculture industry was changing rapidly. Apple, pear, and apricot orchards were being converted to vineyards, driven by the discovery that the local soils and climate were ideal for growing high-quality grapes for fine wines. When I was a teenager, people noted Okanagan wines only for their low prices and matching quality, but my new neighbours in Naramata produced wines that were winning awards around the world. More and more people were coming to the valley specifically for its wines; I even led a couple of weekend “wine and wildlife” tours for visitors from Vancouver to take advantage of this change in focus for tourism. My participants agreed that an exciting morning of birding followed by a delightful lunch on a patio with a glass of chilled Ehrenfelser was hard to beat on a warm spring day.

In the thirteen years since I moved back to the Okanagan, this shift in tourism has continued to the point where nature- and wine-loving visitors make up a significant part of the annual tourist population, although sun-lovers still crowd the beaches in July and August.

To paraphrase James Thurber, “I don’t know much about wine, but I know what I like.” I do, however, know a bit about natural history, and I hope that this book will allow visitors who come for wine or wildlife—or even some hot sunshine—to explore some of the Okanagan’s roads with fresh eyes for its natural treasury and to come away with a richer sense of what makes this valley one of the best places on Earth.

The Natural Okanagan

Although the Okanagan’s reputation for fine weather may be enough to bring visitors from the rain-soaked coast of British Columbia or blizzard-bound Alberta, one natural feature of the valley stands out as an obvious attraction: its diversity. Few places in Canada—or even North America—can boast its combinations of desert sands and deep lakes, towering rock cliffs and rich benchlands, and cold mountain forests and hot grasslands. Freezing winds carve back the needles on stunted firs at tree line, while only a few kilometres away a rattlesnake slides around yellow cactus flowers, hunting for pocket mice. Cattail marshes line river oxbows only a few metres from sagebrush that sends roots deep into dry soils in a constant quest for water.

This wide array of habitats is not only refreshing for the hiker or biker but a real boon to wildlife. The presence of permanent water in such an arid landscape greatly boosts the numbers and varieties of animals able to live in the area. And the statistics are impressive. About 200 species of birds nest in the Okanagan Valley, more than anywhere else in Canada. In fact, few places in North America could boast such an impressive list in such a small area—arctic birds on the mountaintops, boreal forest birds in the spruce, coastal forest birds in the cedars, and southwestern desert birds in the sagebrush. No wonder birders come from all over the continent to the Okanagan to add to their life lists. Every May teams of birders from all over British Columbia participate in the Okanagan Big Day Challenge, competing to see how many kinds of birds they can see in one crazy day in the Okanagan. I was on the team that set the long-standing record of 174 species.

And it’s not just birds, of course. Fourteen species of bats live in the Okanagan, more than anywhere in Canada, including the spectacular spotted bat, which looks like a little flying skunk with oversize pink ears. The valley is also the British Columbia hot spot for reptiles and amphibians, featuring spadefoot toads, tiger salamanders, rubber boas, and, at least formerly, pygmy short-horned lizards. One little pond near Penticton is home to almost half the dragonfly species of British Columbia. Most other invertebrate species are not well surveyed, but the presence of northern scorpions, Jerusalem crickets, and black widow spiders certainly adds spice to a prowl through the grasslands.

Another quality of the natural environment that draws visitors to the Okanagan is rarity. Many of the Okanagan’s plants and animals are found nowhere else in Canada or at least are very difficult to find elsewhere. The canyon wren is found from southern Mexico to the rocky cliffs just south of Kelowna, and the sage thrasher from Arizona to the White Lake Basin west of Okanagan Falls; the Lyall’s mariposa lily grows only on the east slope of the Cascades from central Washington north to Osoyoos; and the list goes on.

In Canada, most of the plants and animals unique to the Okanagan are associated with habitats at low elevations—the dry grasslands on the valley benches and moist woodlands and marshes along the lakes and streams. These habitats, in turn, have been the prime landscapes settled and irrevocably altered by human settlement in the past century. The Okanagan has the biggest concentration of species at risk in the country, and almost all of these species are endangered because of that combination of rarity in Canada and habitat loss. Some estimates suggest that 80 per cent of riparian habitats—the birch woodlands along the old channels of the Okanagan River and the marshes at the head of each lake—and 50 to 70 per cent of grasslands have been lost to agriculture and urban development.

The Building of the Okanagan Valley

Two hundred million years ago, there was no Okanagan Valley. Indeed, very little land stood where British Columbia is today— just the shallow waters of the continental shelf of western North America. Then, starting about 180 million years ago, a series of continental collisions occurred. Large island masses, perhaps similar to Japan or the Philippines, slid into the west coast of North America, carried by drifting continental plates. These landmasses pushed up and overrode the sedimentary rocks on the shelf, creating much of the land area of British Columbia.

The collisions continued off and on until about 60 million years ago, when the dynamics of the colliding plates changed and the tremendous pressure that had built the mountains of British Columbia largely ceased. As the eastward pressure eased, the great piled mass of southern British Columbia slumped back to the west, allowing huge cracks to appear in the land. These cracks—called relaxation faults—are some of the large valleys of British Columbia we know today—including the Rocky Mountain Trench, the Kitimat Trench, and the Okanagan Valley.

As the Okanagan Valley opened, the sedimentary rocks laid down on the old continental shelf of North America rose to the surface after being deeply buried for more than 100 million years. They had been greatly changed—melted and recrystallized into hard metamorphic rocks such as gneiss. The high rock cliffs of the south Okanagan, including the massive wall of McIntyre Bluff north of Oliver, are almost all part of this group. The rifting process that opened the Okanagan Valley was accompanied by a great deal of volcanic activity. Many of the smaller mountains in the valley—for instance, Munson Mountain in Penticton, Giant’s Head in Summerland, Mount Boucherie near Westbank, and Knox, Dilworth, and Layer Cake mountains in Kelowna—are all made of volcanic rock from this period.

For the next 50 million years or so, nothing truly dramatic happened to the Okanagan landscape. Vast outpourings of lava blanketed the Columbia Basin to the south and the Chilcotin Plateau to the northwest; some of these flowed onto the Thompson Plateau at the north end of the Okanagan, cooling into columnar basalts. The mountains slowly eroded, as mountains always do, creating rounded plateaus on either side of the valley.

Then the ice came. About 2 million years ago, the Earth’s climate cooled as the Pleistocene Epoch began. More snow fell each winter, and the summer melt decreased. Snow accumulated rapidly in the mountains of British Columbia, forming glaciers that flowed out of the Coast, Columbia, and Rocky mountains and filled the valleys. The glacier flowing south through the Okanagan Valley grew until it overtopped the plateau on either side and joined other river glaciers to form a vast ice sheet almost 2 kilometres thick. Covering all but the highest peaks in the province, this ice sheet flowed inexorably west to the sea and south over the Okanagan and other valleys to melt on the Columbia Plateau in what is now Washington State. The Pleistocene wasn’t constantly cold; it contained a half-dozen or more long periods within it when the world was warmer than it is today. The glaciers shrank and advanced with each climatic cycle; the latest major advance began about 30,000 years ago and reached its maximum extent about 15,000 years ago. Shortly after this peak, the climate warmed again, and the ice quickly melted back and was more or less gone by 12,000 years ago.

The ice sheet melted from the top down as well as from its leading edges, so the first areas free of ice were the mountaintops and plateaus, and the last remnants of the Pleistocene were huge masses of ice in the valley bottoms. Old rivers flowed again as the ice melted, but they often found their ancient paths blocked by valley glaciers or altered forever by the deep scouring action of the ice. In the south Okanagan, a large, lingering mass of ice created a big plug at the narrowest point of the valley—the rock cliffs south of Vaseux Lake. The Okanagan River backed up to form a large lake, called Glacial Lake Penticton, that stretched 170 kilometres north to Enderby. Like all glacial lakes, it was a milky blue colour from the large amount of fine glacial flour it carried, silt scoured off bedrock by thousands of years of glacial flow.

The glacial flour settled to the bottom of the lake each year, forming a deep layer of pale material called glaciolacustrine silt. The river flowed north out of Lake Penticton into the Thompson and Fraser systems until the plug at McIntyre Bluff melted so that the Okanagan could flow once again into the Columbia. The shaping of the Okanagan Valley was complete—the glaciers had rounded off the plateau hills and cut the valley broad and deep. Like all fiord lakes, Okanagan Lake is very deep—about 232 metres at the deepest point. Meltwater streams filled other parts of the valley with huge amounts of sand and gravel carried down from the scoured plateaus. The glaciolacustrine silts form conspicuous white cliffs along the shores of Okanagan and Skaha Lakes but are noticeably absent south of McIntyre Bluff, the site of the plug that formed Lake Penticton.

Ecosystems

To make sense of the tremendous natural diversity of the Okanagan, it helps to divide the region into ecosystems. At the simplest level, there are four of these: the narrow ribbons of dry grasslands on the benchlands on either side of the valley bottom; the coniferous forests that stretch to the mountaintops; the islands of alpine tundra that cap the highest peaks; and the lakes, rivers, marshes, and other water-rich habitats.

The desert grasslands really characterize the Okanagan and set it apart from other lake-filled valleys in Canada. At first glance, these grasslands might appear to be rather monotonous and less diverse than the forests above, especially on a hot August afternoon when the dry soil crunches underfoot and the songbirds are silent. A closer inspection, however, quickly reveals a beauty and richness equal to any rain forest. The bunchgrasses here differ from grasses of the Canadian prairies in several ways, but primarily in that they actively grow only in spring, when soil moisture is adequate. By July the hillsides are parched, and the grasses, their nutrients stored in a large mass of fibrous roots, turn gold. The grasses wait out the summer drought and winter chill then green up again in spring. Many prairie grasses, adapted to moister summers, do not form distinct bunches but instead grow more evenly across the ground almost like a turf.

If you look at the grass itself, you will see that there are several kinds of bunchgrass common to the Okanagan, each indicating subtle differences in rainfall, temperature, and soil structure. Many valley-bottom grasslands in the south Okanagan are dominated by red three-awn grass, with its thick clumps of fine leaf blades and a three-parted seed head that looks exactly like the centre of a Mercedes-Benz logo. At slightly higher elevations, the southern grasslands are dominated by the tall tufts of bluebunch wheatgrass, with its seeds arranged on vertical stems like tiny beads on a string. This is the archetypal bunchgrass that fed the cattle industry, which in turn shaped the history of the West. Drier locations are often covered by needle-and-thread grass, whose seeds are essentially miniature spears that easily attach themselves to passing cattle and humans. Healthy upper-elevation grasslands in the southern valley, such as those on Anarchist Mountain east of Osoyoos and in the rolling hills around Vernon in the northern valley, are dominated by fescues, bunchgrasses with more feathery seed heads.

But perhaps the commonest grass of all in the Okanagan is a newcomer: cheatgrass. A native of southern Europe, its barbed seeds are shorter and more insidious than those of the needle-and-thread, filling socks and shoes with a mass of painful points. Cheatgrass is an annual plant, its seeds germinating in fall then flowering the following spring. The small plants don’t form bunches; their predilection for overgrazed sites has allowed cheatgrass to blanket entire landscapes across the Intermountain West.

Are these grasslands really a pocket desert, as the area around Osoyoos Lake is often called? The combination of sandy soils, cacti, rattlesnakes, and scorpions certainly fits the public perception of a desert. The annual rainfall is about the same as that of southern Arizona, and no one would dispute that the area around Tucson, with its saguaro cacti, is a desert. But many ecologists say that the presence of perennial grasses in the Okanagan Valley— the bunchgrasses mentioned above—indicates that these grasslands are a steppe. More particularly, they would call it a shrub steppe, because the grasses often grow in association with woody plants such as antelope brush and sagebrush.

Like the different grasses, each of these shrubs adds its own character to the ecosystem. Antelope brush is found in the southern half of the Okanagan Valley; its dark, gangly limbs are often associated with red three-awn, and together the two form one of the most endangered plant communities in the country. The sandy soils are dotted with clumps of brittle prickly pear cacti and serenaded by the songs of the lark sparrow. The present endangerment of this community is due at least in part to its increasing value as prime grape-growing land.

Sagebrush covers the dry hills of the southern valley as well, primarily on the west side. It seems to be found on more loamy soils than antelope brush and is often associated with bluebunch wheatgrass. Several species of birds and other animals are closely tied to sagebrush to the point where they are rarely found more than a stone’s throw from the aromatic grey shrubs. Sage thrashers nest throughout the dry western valleys of North America, north to the White Lake Basin just west of Okanagan Falls. Another songbird with a close attachment to sagebrush is the Brewer’s sparrow, which reaches the northern limit of its range just west of Penticton.

Throughout the grasslands there are scattered ponderosa pines—big, veteran trees with glowing brick-red bark and long green needles. As you climb off the benches and onto the surrounding hills, these trees become more common and quickly coalesce into park-like woodlands. This change from grassland to forest marks the lower tree line. Ponderosa pines are the tree species in this region most tolerant to drought and high summer temperatures. They are the classic conifer of the dry valleys and mountains of the West, evoking images of cowboys riding through sunlit glades. Like sagebrush, ponderosa pine woodlands host a suite of species found in no other habitat. The pygmy nuthatch is perhaps the bird most tightly bound to ponderosa pines; this small bird roams the forests in flocks that comb the furrowed bark and large cones for insects and other food items. A more enigmatic ponderosa pine specialist is the white-headed woodpecker, a strikingly patterned bird that specializes in eating pine seeds through the winter; in Canada this woodpecker is found only in the south Okanagan Valley.

Ponderosa pine forests have changed dramatically in the last century. Indigenous people burned these forests on a rotating schedule for thousands of years, setting fires on cool autumn days to clear out small trees and shrubs that encroached on the grassland understory. The large pines have a very thick bark, allowing them to survive the ground fires and maintain the open, park-like structure—large, scattered trees with a grassy under-story— so characteristic of these dry forests. When the West was settled by Europeans in the late 180 0s and early 19 0 0s, this method of forest management was abruptly stopped, replaced by logging of the large trees and active suppression of fires. Throughout much of the West—and the Okanagan is no exception—this has resulted in dense stands of young ponderosa pines, each fighting for scarce water resources and shading the light-starved plants on the forest floor.

As you climb higher on the hillsides, average temperatures drop and average precipitation increases, and with these differences comes a similar change in tree species. Douglas-fir gradually replaces ponderosa pine; then it, in turn, is replaced by western larch, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine fir. The plateaus on either side of the valley are covered largely by dense growths of lodgepole pine. Ecologists call lodgepole pine a seral species—a tree that pioneers open ground after a fire or logging, then gives way after a century or two to spruce and fir. In recent decades much of the lodgepole pine in British Columbia has been decimated by mountain pine beetles, and as a result, the forest industry has targeted it with massive clearcuts.

A few rounded peaks rise above the upper tree line in the Okanagan Valley. The forest opens up to green meadows with scattered whitebark pine; higher still, the trees are reduced to wind-pruned clumps of twisted branches, and flowers bloom from cushions tucked out of the wind behind lichen-covered rocks. This is alpine tundra, where summers are too short and too cool to allow tree germination.

In a valley with little rainfall, watery habitats play a disproportionate role in shaping the natural landscape. Not only do the large lakes provide year-round water, they also moderate daily temperatures, particularly in winter, allowing species that would otherwise have to move out or hibernate to stay active. And the lush growth around marshes, lakeshores, and river oxbows provides a rich food source used by almost every wildlife species in the valley at one time or another. The broad-leaved trees along the shores—birches, cottonwoods, and aspens—are highly attractive to many birds and mammals. They grow quickly and are commonly attacked by various heart rots, producing hollowed trunks that provide snug homes for woodpeckers, owls, squirrels, raccoons, and many other species.

Like the grasslands, these rich, moist environments have been disproportionately affected by human settlement—lakeshores are naturally the most favoured sites for housing and resort developments. Perhaps the project that affected these habitats the most was the channelization of the Okanagan River in the 1950s. This project completely altered the water flow in the system, flushing spring runoff through the valley as quickly as possible. Salmon runs dwindled, affected by both the drastic changes in local channels and the construction of eleven dams downstream on the Columbia River. The wet meadows and birch woodlands along the old meandering river channel were then converted to agriculture or housing, and as the seasonal flow disappeared, the few that remained became shadows of their former selves.

Climate

The Okanagan Valley has a reputation for being a hot, dry place; the sandy benchland of the Osoyoos area is often called Canada’s pocket desert. The valley does indeed lie in the rain shadow of the Cascade and Coast mountains, and so moist Pacific air is wrung dry as it rises over these ranges on its eastward track in from the ocean. This maritime flow is one of three airstreams that dominate the local climate; the other two are the warm continental flow from the Great Basin to the south and the frigid air that creeps down from the Arctic in winter.

One of the most important factors that affect the Okanagan climate is the presence of large lakes through most of the valley. These lakes significantly moderate the climate throughout the year, warming the valley in winter and cooling it in summer.

The south Okanagan receives about 30 centimetres of precipitation per year. This is certainly less than in most parts of the province, but it is not the driest area—sites such as Ashcroft and Keremeos, tucked into deep valleys in the eastern flank of the Cascade and Coast ranges, often get less than 25 centimetres. Rainfall increases gradually as you go northward in the valley and then rather sharply near the north end; Kelowna gets 31.5 centimetres and Armstrong 44.8 centimetres of precipitation each year.

Spring comes early to the Okanagan in comparison with other inland areas in western Canada. As the days lengthen in February, the track of the Arctic airstream shifts eastward, allowing warm Pacific air to flood in from the coast. The snow quickly melts in the valley bottom, and the first spring flowers—sagebrush buttercups and yellowbells—brighten the golden grasslands. By the end of February, the first spring migrant birds have returned from the south—tree and violet-green swallows take in the early midge hatches over the river, and western meadowlarks sing again. By late March the apricots are blooming white throughout the southern valley, followed in April by the pink peach, white cherry, creamy pear, and white and pink apple blossoms. Wild currants are blooming too, and the first hummingbirds come back to take advantage of the new nectar.

The spring air warms rapidly, and on hot days in late May, you can often see children swimming in the lakes—adults usually wait until July. Most of the birds have returned by the end of May; pink bitterroot blossoms appear as if by magic out of the hot, dry soil, and cottonwood fluff drifts through the air like snow in a summer snowstorm. Although precipitation is relatively even throughout the year in the Okanagan, June is the wettest month. Warm rains melt the deep snowpack in the mountains, and all the creeks swell, sending frigid, silty water into the lakes. Sometime in early July, a strong high-pressure ridge builds to the west, deflecting the moist Pacific airstream north into the Yukon, and the dry and hot days of a classic Okanagan summer settle in, fuelled in part by oven-like air flowing north out of the Great Basin Desert. Young birds leave their nests, and the laneways of the valley fill with scuttling groups of tiny quail.

The Pacific airstream reestablishes itself in late August, bringing fall showers back to the Okanagan. Songbirds such as warblers and flycatchers stream south, heading for winter quarters in Central America. Shorter days and a lower sun bring lower temperatures, and by early October the mean temperature on the mountaintops falls below freezing. The larches on the eastern slopes of the valley turn brilliant gold, and the cottonwoods along the creeks soon follow with a similar show of colour. The frost line drops steadily; the first snow flurries bring temporary washes of white to the valley bottom in November. As small lakes in northern and central Canada freeze, rafts of coots, ducks, and other waterfowl appear on the lakes of the Okanagan.

The real cold is yet to come, however. Sometime in December or early January, the first stream of Arctic air slips through passes in the Rockies and slides into southern British Columbia. Overnight lows drop below –10°C, and vineyards spring into action to harvest the frozen grapes for icewine. Snowfalls now blanket the ground for weeks on end. Snow depths in the south Okanagan rarely exceed 15 centimetres but are regularly over 30 centimetres in Kelowna and even deeper in Vernon. Armstrong receives a total of 135 centimetres of snow each year, compared with only 60 centimetres in the southern parts of the valley. Snowfall also increases with elevation, of course; some subalpine areas can get over 500 centimetres of snow, much to the delight of local skiers.

Early History

As the glaciers receded from the Okanagan, animals and plants recolonized the rock and gravel left behind. The climate warmed quickly, and the landscape was rapidly transformed into a mosaic of forests and grasslands. Among the new arrivals were people who came to hunt the game, harvest the plants, and take the salmon from the reestablished river.

The Native people of the Okanagan call themselves Syilx and are part of the Salish language group. The name Okanagan, first recorded by Lewis and Clark as Otchenaukane in 1805, has an obscure history. It is usually translated as “going towards the head,” but exactly how this word relates to the valley is unclear. One explanation suggests that it refers to people travelling up the Okanagan River to the head of the lake near Vernon, and another refers to seeing the top of sacred Mount Chopaka from near Osoyoos. There were four major settlements in the valley in the late 1800s: one at the north end of Osoyoos Lake at Nk’Mip; one on the flats between Okanagan and Skaha Lakes at Penticton; one at the north end of Okanagan Lake at Nkamaplix; and one at Spallumcheen near Armstrong. These settlements were used throughout the winter, when the people lived in kekulis (circular structures built partly underground for warmth) and ate the foods that they had harvested and stored throughout the warmer months.

In spring, family groups would leave these settlements to travel throughout the Okanagan territory to a complex array of traditional food-harvesting sites, including spring fishing grounds in the Similkameen, bitterroot (speetlum in the Okanagan language) patches on the southern grasslands, and saskatoon berry (siya) patches throughout the valley. In late summer, families would camp in high mountain meadows to pick huckleberries, while others gathered in larger groups at salmon concentrations in the south Okanagan and at Kettle Falls to the southeast. Hunter families would harvest deer and other game in the fall, but as the days shortened and snow began to fall on the mountains, most families would return to the permanent settlements for the winter. Apparently enough resources could be found around Penticton to warrant year-round residence there, since its name means “people always there.”

The earliest Europeans to visit the Okanagan were fur traders; Scotsman David Stuart is reputed to be the first of these to see the valley, in 1811. The Okanagan quickly became an important trade route; furs were packed south from the northern forests of British Columbia to Fort Kamloops, then down the Hudson’s Bay Company Brigade Trail through the Okanagan Valley to the Columbia River at Fort Okanogan, and from there to the Pacific at Fort Vancouver and Fort Astoria. David Douglas, the famous botanist who first identified the Douglas-fir, travelled north along this route in the spring of 1833. The fur trade waned sharply in the middle of the 1800s when silk replaced beaver felt as the latest style in European hat fashion. The Brigade Trail was also replaced by a more western route in 1846, when the establishment of the forty-ninth parallel as the border between the United States and British North America forced Kamloops traders to travel west of the Okanagan to the mouth of the Fraser River.

British Columbia joined Canada in 1871, and one of the first results of that union was the creation of Indian reserves throughout the new province. Reserve boundaries were drawn over a period of years, starting in the late 1870s, and then often redrawn as ranchers and developers lobbied the government for choicer parts of the valley. The reserves changed the lifestyle of the Native population completely: summer food harvests were gradually disrupted, and traditional habitat management tactics, such as prescribed burns, were essentially outlawed immediately.

Cattle, Cherries, and Chardonnay

One of the earliest impacts of European colonization in the Okanagan Valley was the arrival of the cow. In the 1860s large ranching operations were set up to provide beef for the miners who had flocked to British Columbia during the Cariboo Gold Rush and other, similar strikes. By 1864 there were about 14,000 cows in the valley, and that number rose to 26,000 by 1890—about 20 cows for every human. These cattle were grazed year-round on the arid grassland benches in the valley bottom and drastically altered that habitat. The grass species west of the Rocky Mountains evolved without the herds of bison that continually grazed the prairie grasses, so they were not adapted to constant grazing pressure. Much of the low-elevation grasslands changed from thigh-high bunchgrass to dusty stubble.

By 1900 most of the large cattle ranches were being broken up for development. Townsites sprang up throughout the valley, and the dominant agricultural landscape changed from ranches to orchards. Early orchards were irrigated by a system of flumes and canals that diverted water from local creeks to the upper parts of the orchards. Water was directed through the trees by a series of smaller ditches. In the early 1900s, ground crops such as tomatoes, cantaloupes, and watermelons were extensively planted between trees, but as the trees matured into full production, these crops were phased out. Many early orchardists also kept cattle and chickens for extra income, growing alfalfa between the trees for forage.

Agricultural development continued through the first half of the 1900s, so that by 1950, almost all the private land in the valley bottom was either urban or orchard. Agriculture dominated the local economy; forestry activities in the early 1900s were concentrated on providing timber for local development, including the construction of flumes and apple boxes.

A few vineyards were planted as early as the 1920s, and Calona Wines began production in the late 1930s. The wine industry blossomed in the 1960s and 1970s but generally produced inexpensive and decidedly inferior wines. In 1984 Canada and the United States signed a free trade agreement that allowed duty-free importation of American grapes for processing in the few large Okanagan wineries. Many predicted that this would spell the end of the Okanagan vineyards, and large acreages of vines were pulled up, particularly along Black Sage Road in Oliver. However, a few small estate wineries were having remarkable success with European vinifera grapes, and the number of these small operations began to grow quickly. As of 2008, more than 100 wineries in the Okanagan and Similkameen valleys use grapes from more than 3,000 hectares of vineyards. Winemakers have found that the long, hot summers at the south end of the valley are ideal for Bordeaux varietals such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Merlot, while vineyards in the cooler, northern sections of the valley are well situated for German wines such as Gewürztraminer, Riesling, and Siegerrebe.

Now the orchardists struggle most with cheap imported fruit, and grape growing provides better monetary returns than almost every tree fruit except cherries. As apple, apricot, pear, and peach prices remain in the doldrums, every winter now brings new scenes of orchards being pulled up, burned, and replaced with the more lucrative vines.

More than just the agricultural scene is changing in the Okanagan. The valley has always been a favoured destination for people, luring them with its mild climate, warm waters, and diverse wildlife. Each year new residents arrive, pushing housing developments upslope into pine forests and filling marshlands with condos. But unlike their predecessors, most of these new colonists are choosing the Okanagan for its natural beauty, and hopefully, they will promote the intelligent regional planning necessary to preserve this richness.

This book explores that natural legacy along a series of highways and byways throughout the valley. Some of the subjects of discussion can be easily seen from a moving car—the black snags of a forest fire, hillsides covered in spring flowers, an osprey landing on its pole-top nest with a big carp. To see other fascinating denizens of the valley requires occasional stops and walks through the grasslands and forests. If the weather permits, drive along with your windows open so that you can smell the soft aromas of sagebrush and pine and hear the meadowlarks sing. Some of the routes described are short drives that can be completed in less than an hour, whereas a few are more ambitious and could be all-day adventures.