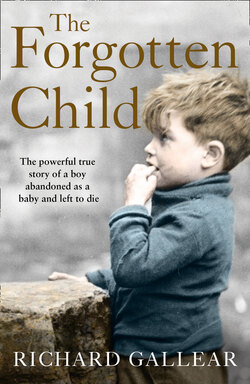

Читать книгу The Forgotten Child - Richard Gallear - Страница 7

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Left to Die

‘What was that?’ The whispered words faded to echoes in the dark mists of that frozen night, 17 November 1954.

Postman Joseph Lester had just finished his shift at Birmingham’s sorting office and started out on his walk home along Gas Street, through the gap in the wall and down to the canal towpath at Gas Street Basin. It was nine o’clock; the temperature was two degrees below zero. Tired and shivering cold, he was keen to get back to his family in Ledsham Street and relax in front of a roaring fire. This was his usual shortcut home, so he knew his way through the fog that thickened the darkness and stayed well clear of the water’s edge. There was nobody about – just the unseen lapping of water and the muffled, almost inaudible sounds of the city all around … until that faint something, a sort of whimper.

Joseph pointed his torch where he thought it came from, but he found it almost impossible to see anything. He retraced his steps and tried again, shining the beam to and fro over the water and straining his eyes to pick any form out of the darkness. As he moved his torch for one last sweep over the canal, the beam caught something pale. Was it his imagination? Had it moved?

There it was again. An eerie sound, was it a wounded animal? Surely even a rat wouldn’t venture out on this wintry night. But rats aren’t usually pale coloured. Could it be a kitten, or maybe the shape was just a piece of paper?

Joseph hesitated. It was probably nothing worth stopping for, but something niggled at him, making him turn back from his homeward path. He picked his way over the main bridge and round the basin to the other side, where he knew there was another low bridge, which was about where he thought the pale object must be. Sure enough, as he approached it from the back, he heard that sound again, fainter still. Whatever it was, he needed to find it soon. He clambered down and under the bridge, ducking to shine his torch through the profuse undergrowth.

‘There it is!’ he said out loud to himself, reaching what looked like a parcel wrapped in newspaper, only two or three inches from the water’s edge. But this was no normal parcel. As he peeled back the paper, he found inside a scrawny newborn baby, white, cold and whimpering. Joseph was shocked beyond belief: he’d seen rats as big as cats down there, capable of attacking this baby or pushing him into the canal.

He wrapped him up again and placed him inside his coat, holding him close to try to warm him, and turned to go back up to the street, where he knew there was a phone box to dial 999. Police Constable Watson came to meet Joseph and took his name, then noted down his brief account of finding the baby.

‘Well done, mate,’ he told him. ‘You might have saved a life tonight.’

Joseph smiled and went on his way, back to his wife and children. Meanwhile, the policeman hailed a squad car and took the baby straight to the Accident Hospital, where he was rushed through and seen straight away. A nurse gently opened up the two layers of newspaper and removed the thin, stained blanket beneath. She gasped when she saw the baby’s roughly cut umbilical cord.

‘Do you think the mother gave birth alone?’ she asked.

‘Yes, it looks like it,’ said the doctor. ‘And he looks underweight, probably premature.’ Clearly shocked, he examined the boy. ‘He’s only about two hours old, and his temperature is very low,’ he said as he gently rubbed the baby’s fragile skin in an attempt to warm him up. ‘He’s suffering from exposure. It’s touch and go, I’m afraid.’

Another nurse arrived and weighed him before swaddling him in a soft, warm blanket.

‘Call the night sister,’ ordered the doctor. ‘And see if you can find the Chaplain. This baby needs to be baptised, he may not survive the night.’

The night sister came and the Chaplain too.

‘What name shall I give him?’ he asked.

‘Any ideas?’ the night sister asked the nurses.

‘He looks like a Richard,’ suggested one of them, so that was the name he was given.

‘We must transfer him to Dudley Road Maternity Hospital,’ said the doctor. ‘They can put him in an incubator to give him the best chance. Can you arrange that please, Sister?’

As they waited for the paperwork to be completed, the nurses gathered round baby Richard, who had by now regained a little colour and started to cry and kick his legs up. Everyone smiled to see him protesting.

‘He’s a determined little mite,’ said the doctor. ‘He might just make it.’

One of the nurses accompanied the baby in an ambulance to the Dudley Road Maternity Hospital, where they were better equipped to look after him.

On admission to Ward D6 and placed in an incubator, Richard rallied and his temperature normalised. Not only did he survive the night, he became the nurses’ favourite.

Meanwhile, the next day’s newspapers were full of articles about the abandoned ‘canal-side baby’. The headlines read: ‘BABY LEFT ON CANAL BANK’, ‘NEW-BORN BABY FOUND WRAPPED IN NEWSPAPER’, ‘CHILD FOUND UNDER BRIDGE’, ‘POLICE SEARCH FOR MOTHER’. In fact, the police used the newspapers to put out pleas for the mother to come forward, or for any information, but there was no response. It seemed the baby would have no parents named on his birth certificate.

Almost hour by hour, Richard’s condition improved and he began to flourish. ‘DAY-OLD BABY IMPROVING’ was one of the second day’s headlines.

Later that day, a woman was brought into Dudley Road Maternity Hospital and admitted for treatment, suffering complications after giving birth. She gave her name and address, but would say no more. However, with the press still badgering the hospital for news of the abandoned baby’s progress, an astute nurse suspected a link. The police were alerted and sent round a constable to question the woman in her hospital bed. At first silent, her weakened state left her vulnerable. Within minutes, she broke down and admitted she was the woman they were looking for. However, she didn’t give much away at that stage – just that she had given birth that evening at her lodgings (a story that would later prove to be untrue) and wandered round with the baby, tired and confused, before laying him down under the canal bridge.

While in hospital, it seems, she did not request to see the baby. However, had she asked, she would not have been permitted to visit him while the police were investigating the case.

The next morning’s newspapers triumphantly carried the story on their front pages: ‘CANAL-SIDE BABY: MOTHER TRACED’ and other similar headlines.

Now the police charged her with abandonment and started to gather evidence from postman Joseph Lester, PC Watson, the first policeman on the scene, the doctor at the hospital where the baby was first admitted, and anyone else they could find.

On 22 December, Richard’s birth mother was in the dock at Birmingham Magistrates’ Court, where she had no alternative but to plead guilty to ‘abandoning the child in a manner likely to cause it unnecessary suffering or injury’. The press reported the case in considerable detail.

The prosecution set out the evidence, explaining how the baby was found by the canal, very close to the water’s edge, and the state he was in: ‘The weather was bad. Exposure had endangered the baby’s life and it was not likely the child would have lived, but for the keen observation of Mr Lester.’

The mother’s counsel told the court that she was afraid of losing her lodgings and possibly her job too. ‘And the fact that the baby was born prematurely, when she got home from work,’ he explained, ‘caused her to act in an unnatural manner.’

‘I hope you realise the gravity of your offence,’ the magistrate scolded her. All the available evidence, which was not very much, was heard. Finally, the magistrate looked straight at the mother and said: ‘You might have faced a charge of infanticide, for what you did could have resulted in the child’s death.’

Oblivious to all this, baby Richard was basking in the affection showered on him by the nurses in Ward D6 and only a day or two after his arrival was well enough to thrive outside the incubator. He fed hungrily and was soon ready to be discharged from hospital. On 28 November, just 11 days after his birth, the duty doctor wrote a letter to Birmingham Children’s Officer:

The following day, a form was filled in at Birmingham Children’s Department to take over responsibility for him.

That afternoon, the nurses gathered to wave off baby Richard as he was handed over to a woman from the Children’s Department, who took him to Field House Nursery – the place that would become his first real home.