Читать книгу The Blackmailers: Dossier No. 113 - Richard Dalby - Страница 5

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

ÉMILE Gaboriau’s ingenious creation Monsieur Lecoq was the first important literary detective to be featured in a series of novels during the 1860s. Published midway between Edgar Allan Poe’s three celebrated stories featuring C. Auguste Dupin (including ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’) in the early 1840s and Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel in 1887, Monsieur Lecoq was also an exact contemporary of Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (1868), considered to be Britain’s first classic detective novel.

Gaboriau moved ahead of his contemporaries by focusing attention on the gathering and interpretation of evidence in the detection of crime. Historically he is second only to Poe in creating pure detective fiction, by writing the first novels in which the nature of the crime, the role of the detective, the misdirections, the reader participation and the solution are all carried through successfully in the contemporary manner, a great inspiration to all who followed in this genre.

Émile Gaboriau was born in the town of Saujon, France, on 9 November 1832, the son of a notary. He spent seven years in the cavalry before settling in Paris, where he wrote poetic mottoes for birthday cakes and songs for street singers.

He then became assistant, secretary and ghost-writer to Paul Féval, author of widely-read criminal romances for feuilletons (inserted as supplements in daily newspapers). Gaboriau gathered much of his material in police courts for Féval, and in 1858 broke away to begin work on his own serialised novels.

After writing seven popular romances, Gaboriau produced his first detective novel, L’Affaire Lerouge, which began its newspaper serialisation in September 1865, and was published in book form the following year. In this story, Gévrol, chief of the detective police in the Paris Sûreté, is in charge, but the major detection is provided by Père Tabaret, an amateur consultant who explains his methods to the young Lecoq. Tabaret has studied the literature of crime for a long time and worked by ratiocination, or precise thinking, to solve a very deceptive crime, said to have been based on a contemporary murder.

Lecoq began in L’Affaire Lerouge as a minor detective with a shady past who had previously contemplated illegal methods of gaining wealth before joining the Sûreté. His career was inspired and closely based on the life and memoirs of the real-life detective Eugène François Vidocq (1775–1857), who also joined the Sûreté after a life of crime.

After his début, Lecoq had much more important leading roles in Le Crime d’Orcival (1867), Le Dossier No.113 (1867), Les Esclaves de Paris (1868, initially in two volumes), and Monsieur Lecoq (1869, also in two volumes). These enthralling mysteries ensured that Lecoq gained countless admirers throughout Europe, including the statesmen Benjamin Disraeli and Otto von Bismarck. As Gaboriau’s reputation grew, so were his novels translated and published in the UK, but none were more successful than the bestselling Lecoq quintet, issued by Routledge in the summer of 1887 in cheap paperback and yellowback editions under the titles The Widow Lerouge, The Mystery of Orcival, File No.113, The Slaves of Paris and Monsieur Lecoq.

In addition to becoming a master of disguise, Lecoq developed valuable crime-fighting techniques, such as using plaster to make impressions of footprints and devising a test of when exactly a bed has been slept in. He was always a supreme master of excavating and analysing deeply-buried vital clues. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the first Sherlock Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet, followed shortly after the Routledge paperbacks, at Christmas in the same year.

Émile Gaboriau died suddenly on 28 September 1873, supposedly of ‘overwork’, aged only 40, having written 21 novels in thirteen years (fourteen of them in his last seven years of life). He described his works as romans judiciaires, a crime-mystery form much imitated by writers in the century to come.

The third Monsieur Lecoq novel, Le Dossier No.113, was first translated into English in 1875 and published by A. L. Burt in New York. The work was copyrighted to James R. Osgood & Co., but the identity of the translator was not given. Running to 145,000 words, the English translation was literal and rather cumbersome, although the book proved to be popular and was reissued by a number of publishers many times over the next four decades.

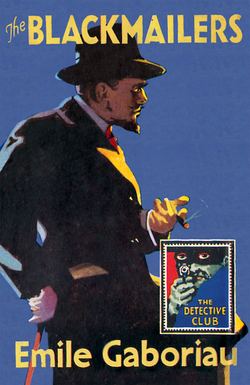

In 1907, a new translation by Ernest Tristan was published by Greening & Co. under the more evocative title The Blackmailers, a complete but more efficient interpretation of the book that halved its page count. It was this version that William Collins Sons & Co. of Glasgow later released in their rapidly expanding series of Pocket Classics. Also selected as the sixth book in Collins’ new Detective Story Club imprint, it was published in September 1929 with typical fanfare:

‘Émile Gaboriau is France’s greatest detective writer. The Blackmailers is one of his most thrilling novels, and is full of exciting surprises. The story opens with a sensational bank robbery in Paris, suspicion falling immediately upon Prosper Bertomy, the young cashier whose extravagant living has been the subject of talk among his friends. Further investigation, however, reveals a network of blackmail and villainy which seems as if it would inevitably close round Prosper and the beautiful Madeleine who is deeply in love with him. Can he prove his innocence in the face of such damning evidence?’

The story was filmed in Hollywood in 1932 under the older title File No.113, starring Lew Cody as the subtly renamed ‘Le Coq’.

Although Gaboriau’s fame and reputation were inevitably overshadowed by newer crime writers after his death, he was later championed by several discerning critics including the novelists Valentine Williams (in a 1923 landmark essay, ‘Gaboriau: Father of the Detective Novel’) and Arnold Bennett, who praised all the Lecoq novels in 1928, stating that they are ‘brilliantly presented and, besides the detection and crime-solving, Gaboriau was able to provide a really good, sound and emotional novel’.

After 150 years, Gaboriau’s novels will always deserve to be savoured, appreciated and rediscovered by connoisseurs of early detective fiction.

RICHARD DALBY

January 2016