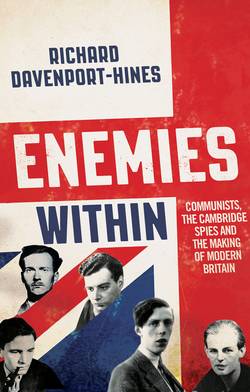

Читать книгу Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain - Richard Davenport-Hines - Страница 18

The political culture of everlasting distrust

ОглавлениеThe most effective British Ambassador to Stalinist Russia was Sir Archie Clark Kerr, who was created Lord Inverchapel as a reward for his success. ‘Nearly all of those who now govern Russia and mould opinion have led hunted lives since their early manhood when they were chased from pillar to post by the Tsarist police,’ he wrote in a dispatch of December 1945 assessing diplomacy in the new nuclear age. ‘Then came the immense and dangerous gamble of the Revolution, followed by the perils and ups and downs of intervention and civil war.’ Later still came the deadly purges, when ‘no one of them knew today whether he would be alive tomorrow’. Through all these years Soviet apparatchiks ‘trembled for the safety of their country and of their system as they trembled for their own’. Their personal experiences and their national system liquidated trust and personal security.45

Stalin achieved supremacy by implementing a maxim in his book Concerning Questions of Leninism: ‘Power has not merely to be seized: it has to be held, to be consolidated, to be made invincible.’ To Lev Kamenev, whom he was to have killed, he said: ‘The greatest delight is to mark one’s enemy, prepare everything, avenge oneself thoroughly, and go to sleep.’ Dissidents who had fled abroad were assassinated. In 1938, for example, Evgeni Konovalets, the Ukrainian nationalist leader, was killed in Rotterdam by an exploding chocolate cake. Stalin compared his purges and liquidations to Ivan the Terrible’s massacres: ‘Who’s going to remember all this riffraff in twenty years’ time? Who remembers the names of the boyars Ivan the Terrible got rid of? No one … He should have killed them all, to create a strong state.’46

Stalin rewarded his associates with privileges so long as they served his will. ‘Every Leninist knows, if he is a real Leninist,’ he told the party congress of 1934, ‘that equality in the sphere of requirements and personal life is a piece of reactionary petit-bourgeois stupidity, worthy of a primitive sect of ascetics, but not of a socialist society organized on Marxist lines.’ But Stalin was pitiless in ordering the deaths of his adjutants when they no longer served his turn. The first member of his entourage to be killed on his orders was Nestor Apollonovich Lakoba, who was poisoned during a dinner at which his attendance was coerced by Stalin’s deadly subordinate Lavrentiy Beria in 1936. Beria then maddened Lakoba’s beautiful widow by confining her in a cell with a snake and by forcing her to watch the beating of her fourteen-year-old son. She finally died after a night of torture, and the child was subsequently put to death.47

The enemies of the people were not limited to saboteurs and spies, Stalin said at the time that he launched his purges. There were also doubters – the naysayers to the dictatorship of the proletariat – and they too had to be liquidated. The first of the notorious Moscow show-trials opened in August 1936. Chief among the sixteen defendants were Zinoviev and Kamenev, who had agreed with Stalin to plead guilty and make docile, bogus confessions in return for a guarantee that there would be no executions and that their families would be spared. They were faced by the Procurator General, Andrei Vyshinsky, the scion of a wealthy Polish family in Odessa, who had years before shared food-hampers from his parents with his prison cell-mate Stalin. Vyshinsky was ‘ravenously bloodthirsty’, in Simon Sebag Montefiore’s phrase, producing outrushes of synthetic fury at need, and using his vicious wit to revile the defendants as ‘mad dogs of capitalism’. The promises of clemency were ignored, and when all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death, there was a shout in court of ‘Long live the cause of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin!’ Stalin never attended executions, which he treated as ‘noble party service’ and which were officially designated the Highest Measure of Punishment. Vyshinsky seldom saw the kill, for he too was squeamish. At the Lubianka prison, Zinoviev cried: ‘Please, comrade, for God’s sake, call Joseph Vissarionovich [Stalin]! Joseph Vissarionovich promised to save our lives!’ He, Kamenev and the others were shot through the back of the head. The bullets, with their noses crushed, were dug from the skulls, cleaned of blood and brains, and handed (probably still warm) to Genrikh Grigorievich Yagoda, the ex-pharmacist who had created the slave-labour camps of the Gulag and was rewarded with appointment as Commissar General of State Security.48

Yagoda, who was a collector of orchids and erotic curiosities, labelled the bullets ‘Zinoviev’ and ‘Kamenev’, and treasured them alongside his collection of women’s stockings. At a subsequent dinner in the NKVD’s honour, Stalin’s court jester Karl Pauker made a comic re-enactment of Zinoviev’s desperate final pleading, with added anti-semitic touches of exaggerated cringing, weeping and raising of hands heavenwards with the prayer, ‘Hear oh Israel the Lord is our God.’ Stalin’s entourage guffawed at this mockery of the dead: the despot laughed so heartily that he was nearly sick. A year later Pauker himself was shot: ‘guilty of knowing too much and living too well: Stalin no longer trusted the old-fashioned Chekists with foreign connections’. When Yagoda in turn was exterminated in 1938, the ‘Zinoviev’ and ‘Kamenev’ bullets passed ‘like holy relics in a depraved distortion of the apostolic succession’ to his successor Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov. Two years later Yezhov was convicted of spying for Polish landowners, English noblemen and Japanese samurai. When taken to a special execution yard, with sloping floor and hosing facilities, Yezhov’s legs buckled and he was dragged weeping to meet the bullet. Similarly the executioner who shot Beria after Stalin’s death stuffed rags in his mouth to stifle the bawling.49

Denis Pritt attended the first Moscow show-trials of 1936. A former Tory voter and a King’s Counsel with a prosperous practice in capitalist Chancery cases, he had turned Red, and became the barrister chosen by the CPGB to defend party members accused of espionage. For fifteen years he was MP for North Hammersmith: after his expulsion from the Labour party in 1940 he continued for a decade to represent the constituency as a communist fellow-traveller; he was rewarded with the Stalin Peace Prize. ‘The Soviet Union is a civilised country, with … very fine lawyers and jurists,’ Pritt reported of a criminal state which deprived its subjects of every vestige of truth. The Moscow trials were a ‘great step’ towards placing Soviet justice at the forefront of ‘the legal systems of the modern world’. Vyshinsky, he said, resembled ‘a very intelligent and rather mild-mannered English businessman’, who ‘seldom raised his voice … never ranted … or thumped the table’, and was merely being forthright when he called the defendants ‘bandits and mad-dogs and suggested that they ought to be exterminated’. Any doubts about the guilt of Zinoviev and Kamenev were dispelled for Pritt by ‘their confessions [made] with an almost abject and exuberant completeness’. None of the defendants had ‘the haggard face, the twitching hand, the dazed expression, the bandaged head’ familiar from prisoners’ docks in capitalist jurisdictions. Bourgeois critics who vilified socialist justice exceeded the bounds of plausibility: ‘if they thus dismiss the whole case for the prosecution as a “frame-up”, it follows inescapably that Stalin and a substantial number of other high officials, including presumably the judges and the prosecutors, were themselves guilty of a foul conspiracy to procure the judicial murder of Zinoviev, Kamenev, and a fair number of other persons’.50

Stalin’s obsession with ‘wreckers’ and ‘saboteurs’ working within the Soviet Union is certainly a projection of Moscow’s activities abroad: plans and personnel for sabotage of British factories, transport and fuel depots in the event of the long-expected Anglo-Russian war were probably extensive. More than ever, after the purges, Stalin used gallows humour to intimidate his entourage. At a Kremlin banquet to welcome Charles de Gaulle in 1942, he proposed a toast: ‘I drink to my Commissar of Railways. He knows that if his railways failed to function, he would answer with his neck. This is wartime, gentlemen, so I use harsh words.’ Or again: ‘I raise my glass to my Commissar of Tanks. He knows that failure of his tanks to issue from the factories would cause him to hang.’ The commissars in question had to rise from their seats and proceed along the banqueting table clinking glasses. ‘People call me a monster, but as you see, I make a joke of it,’ he chuckled to de Gaulle. Later he nudged the Free French leader and pointed at Molotov confabulating with Georges Bidault: ‘Machine-gun the diplomats, machine-gun them. Leave it to us soldiers to settle things.’51

Soviet Russia killed its own in their millions, tortured the children of disgraced leaders, urged other children to denounce their parents for political delinquency, used threats of the noose or the bullet as a work-incentive for its officials, and built slaughter-houses for the extermination of loyal servants. ‘There are no … private individuals in this country,’ Stalin told a newly appointed Ambassador in Moscow, Sir Maurice Peterson, in 1946. The best-organized and most productive Stalinist industry was the falsification of history. Blatant lies were symbols of status: the bigger the lies that went unchallenged, the higher one’s standing. Communist Russia liquidated trust throughout its territories. Every family constantly scrutinized their acquaintances, trying to spot the informers and provocateurs, or those who by association might bring down on them the lethal interest of the secret police. By the culmination of the purges in 1937, people were too scared to meet each other socially. Independent personal judgements on matters of doctrinal orthodoxy became impermissible. As Hugh Trevor-Roper noted in 1959, ‘the Russian historians who come to international conferences are like men from the moon: they speak a different language, talk of the “correct” and “incorrect” interpretations, make statements and refuse discussions’. When after thirty years of internal exile, Nadezhda Mandelstam returned to Moscow in 1965, she found that fear remained ubiquitous. ‘Nobody trusted anyone else, and every acquaintance was a suspected police informer. It somehow seemed as if the whole country was suffering from persecution mania.’52

In Stalin’s toxic suspicions we reach the kernel of this book: the destruction of trust. Purges, so Nikolai Bukharin told Stalin in 1937, guaranteed the primacy of the leadership by arousing in the upper echelons of the party ‘an everlasting distrust’ of each other. Stalin went further, and said in Nikita Khrushchev’s presence in 1951, ‘I’m finished, I trust no one, not even myself.’ Soviet Russia’s ultimate triumph was to destroy reciprocal trust within the political society of its chief adversary.53