Читать книгу The Wood for the Trees: The Long View of Nature from a Small Wood - Richard Fortey - Страница 7

1 April

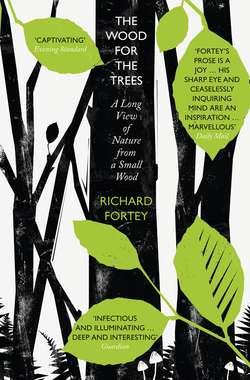

ОглавлениеAfter a working life spent in a great museum, the time had come for me to escape into the open air. I spent years handling fossils of extinct animals; now, the inner naturalist needed to touch living animals and plants. My wife Jackie discovered the advertisement: a small piece of the Chiltern Hills up for sale. The proceeds from a television series proved exactly enough to purchase four acres of ancient beech-and-bluebell woodland, buried deeply inside a greater stretch of stately trees. The briefest of visits clinched the deal – exploring the wood simply felt like coming home. On 4 July 2011 ‘Grim’s Dyke Wood’ became ours.

I began to keep a diary to record wildlife, and the look and feel of the woodland as it passed through diverse moods and changing seasons. I sat on one particular stump to make observations, which I wrote down in a small, leather-bound notebook. I was unconsciously compiling a biography of the wood – bio in the most exact sense, since animals and plants formed an important part of it. Before long, I saw that the story was as much about human history as it was about nature. For all its ancient lineage, the wood was shaped by human hand. I needed to explore the development of the English countryside, all the way from the Iron Age to the recent exploitation of woodland for beech furniture or tent pegs. I was moved by a compulsion to understand half-forgotten crafts and revive half-remembered words like ‘bodger’, ‘spile’ and ‘bavin’. Plans were made to fell timber, to follow the journey from tree to furniture; to visit the canopy in a cherry-picker; to explore the archaeology of that ancient feature, Grim’s Dyke, that ran along one side of the plot. I wanted to see if the wood could yield food as well as inspiration.

My scientific soul reawakened as I sought to comprehend the ways that plants and animals collaborate to generate a rich ecology. I had to sample everything: mosses, lichens, grasses, insects, and fungi. I investigated the natural history of beech, oak, ash, yew, and all the other trees. I spent moonlit evenings trapping moths; daytime frolicking with nets to catch crane flies or lifting up rotten logs to understand decay. I poked and prodded and snuffled under brambles. I wanted to turn the appropriate bits of geology into tiles and glass. The wood became a route to understanding how the landscape is forever in a state of transition, for all that we think it unchanging. In short, the wood became a project.

Grim’s Dyke Wood is just a segment in the middle of more extensive ancient woodland, Lambridge Wood, lying in the southern part of the county of Oxfordshire. Splitting Lambridge into separate plots generated a profit for the previous owner, but also allowed people of modest means to own and care for their own small piece of living history. Our fellow ‘woodies’ – as Jackie terms them – proved to include a well-known harpsichordist, a retired professor of business systems, a founder member of Genesis (the band, not the book), a virologist turned plant illustrator, ex-actors turned psychologists, and a woman of mystery. Our own patch is one of the smaller ones. All of the ‘woodies’ have their own reasons for wanting to be among the trees – some desire simply to dream, some would rather like to turn a profit, others to explore sustainable resources. I believe I am the only naturalist. All the owners are there to prevent the wood from being felled or turned into housing. For the long history of Lambridge Wood tells us that our trees are less worked today than at any time in the past. This sad redundancy is no less part of its tale, as our wood is inevitably connected to the wider world of commerce and markets. The histories of my home town, Henley-on-Thames, a mile away, and the famous river on which it sits, are bound into the narrative of the surrounding countryside. Ancient manors controlled the fate of woodlands for centuries. I have to imagine what the wood would have seen or heard as great events passed it by; who might have lurked under the trees, what poachers and vagabonds, poets or highwaymen.

Once the project was under way a curious thing happened. I wanted to make a collection. This may not sound particularly remarkable, but for somebody who had worked for decades with rank after rank of curated collections it was rejuvenation. Life among the stacks in the Natural History Museum in London had stifled my acquisitiveness, but now something was rekindled. I wanted to collect objects from the wood, not in the systematic way of a scientist, but with something of the random joy of a young boy. Perhaps I wanted to become that boy once again. Eighteenth-century gentlemen were wont to have cabinets of curiosities in which they displayed items that might have conversational or antiquarian interest. I wanted to have my own cabinet of curiosity. I would add items when my curiosity was piqued month by month: maybe a stone, a feather, or a dried plant – nothing for the eighteenth-century gent. I believe that curiosity is a most important human instinct. Curiosity is the enemy of certainty, and certainty – particularly conviction that other people are different, or sinful, or irreligious – lies behind much of the conflict and genocide that disfigure human history. If I could issue one injunction to humankind it would be: ‘Be curious!’ My collection will be a way of encapsulating the whole Grim’s Dyke Wood project: my New Curiosity Shop. And I already know that the last item to be curated will be the leather-bound notebook.

The collection requires a cabinet to house it. Jackie and I plan to fell one of our cherry trees and convert it into a wonderful receptacle for the wood’s serendipitous treasures. We must discuss the work with Philip Koomen, a noted Chiltern furniture-maker devoted to using local materials. Philip’s workshop, Wheelers Barn, is in the remotest part of the Chiltern Hills, only about five miles from Grim’s Dyke Wood as the crow flies, but about fifteen as the ancient roads wind hither and thither. His studio is imbued with calm. Polished sections through trees hanging on the walls show the qualities of each variety: colour, texture, grain, and age all combine to distinguish not just different tree species, but individual personalities. No two trees are identical. Some have burrs that section into turbulent swirls. Pale ash contrasts with rich walnut, and cherry with its warm tones is satisfactorily different from oak. This is a man who cares deeply about materials and believes in the genius loci – an integration of human and natural history that lends authenticity to a hand-made item. Philip’s handiwork from our own cherry tree will be a physical embodiment of our wood, but by housing the idiosyncratic collection picked up as the project develops it will also contain the wood, as curated by this writer. It will be a cabinet of memories as much as objects. We haggle a little about design, but I know I shall rely on his judgement. I will have to be patient when I gather up the small things in the wood that take my fancy. It will be some time before the collection can live in its dedicated home.

This book could be thought of as another kind of collection. Extracts from my diary describe the wood through the seasons. I follow H.E. Bates’s wonderful book Through the Woods (1936) in beginning in the exuberant month of April rather than with the calendar year, and frigid January. But then, H.E. Bates himself inherited the same plan from the writer and illustrator Clare Leighton, whose intimate portrait of her own garden through the cycles of the seasons, Four Hedges,1 he much admired. My friends and colleagues come to sample and identify almost every jot and tittle of natural history that they can find. Natural history leads on to science, and the stories of grand estates, woodland skills and trades, and life along the River Thames. Human folly and natural catastrophes link the wood to a wider world beyond the trees. This complex collection explains why the wood is as it is today; its rich diversity of life is a concatenation of particular circumstances. I am trying to reason how the natural world came to be so varied, and my understanding is refracted through the lens of my own small patch. I am trying to see the wood for the trees.

Bluebells

Some trees stand close together, like a pair of friends huddling in mutual support. Others are almost solitary, rearing away from their fellows in the midst of a clearing. The poet Edward Thomas described ‘the uncounted perpendicular straight stems of beech, and yet not all quite perpendicular or quite straight’.2 Each tree trunk has individuality, for all the harmony of their numbers together. One leans a little towards a weaker neighbour; another carries a scar where a branch fell long ago; this one has an extraordinarily slender elegance as it reaches for its place under the sky; that one has a stocky base, as chunky as an elephant’s leg, and doubtless at least as strong. No two trees are really alike, yet their collaboration on the scale of the wider wood creates a sense of architectural design. The relatively pale and smooth beech bark helps to unite the structure, for in the early spring’s soft sunshine the tree trunks shine almost silver. The natural cathedral of the wood is supported by brilliant, vertical superstructure, one that shifts subtly with the moods of the sun.

It is too early in the month for many fresh beech leaves to have unfurled from their tight buds. The wood is still flooded with light. Some of the sunlight falls on the crisp, dark tan to gold-coloured leaves fallen from last year’s canopy that lie in scruffy patches on the ground; stubbornly dry, they have yet to rot away. The sunshine brings the first direct heat of the year, enough to warm our cheeks with hints of seasons to come. Am I imagining that the beech trunk is actually hot on its illuminated side? It does not strain the imagination to envisage the sap rising beneath the grey-green roughened bark, rejuvenated by April showers. Where the sunlight reaches the thin soil spring flowers accept the warmth and light; briefly, it is their time to flourish. After standing to contemplate the grandeur I now have to get down on my hands and knees to see what is happening at ground level. By the pathside are patches of heart-shaped leaves mottled with white; the sun glances off the tiny, glossy, butter-yellow petals of the lesser celandine, eight petals in a circle per flower, not unlike a child’s first drawing of what every flower should be. Celandines are growing in the company of dog violets, whose flowers are as complicated as the celandine’s are simple: the whole borne on an arched-over stem, carrying five blue-violet petals, of which the lowest is lip-like and marked with the most delicate dark lines converging towards the centre of the flower. At the very heart of it there is a subtle yellowing and, behind, a spur offering a treasure of nectar: clearly the whole structure is an inducement for pollinating insects – a road map promising a reward. Through the beech litter brilliant green blades of a grass, wood melick, are pushing upwards to seek their share of precious light. Near the edge of the wood, lobed leaves of ground elder form a mat of freshest green; this notorious garden weed is constrained to behave itself in the wild.

But close observations of wayside flowers may be something of a distraction from a Chiltern spectacular. Perhaps I prefer to taste a few appetisers before becoming overwhelmed by the main course. For just beyond a short sward of wood melick is a shoreline edging the glory of the April beech woods in England: a sea of bluebells. The whole forest floor beyond is coloured by thousands upon thousands of flowers; a sea – because it seems unbroken and intense, like the yachted waters in a Dufy painting. But the display might equally be described as a carpet of bluebells; that word is more appropriate to the floor of a natural cathedral. Besides, the hue is a dark and rich blue, a shade not truly belonging to the ocean. Rather it is the cobalt blue of decorated tin-glazed wares produced at Delft, in Holland. In these woods, a magical slip is washed over the floor of the woodland as if by the hand of a master; a glaze that lasts only a few weeks, but transforms the ground beneath the beeches. From a distance there is a vague fuzziness about it, as if the blueness were evaporating upwards. The show is produced by massed English bluebells, Hyacinthoides non-scripta, a species unique to western Europe. This is old Britain’s very own, very particular and extraordinarily beautiful celebration of early spring. There is no physical sign in our wood of the Spanish bluebell interloper Hyacinthoides hispanica, the common species in English gardens. It is a coarser plant, with a more upright spike of flowers, and generally less elegant. In many places it is hybridising with the native species.

Each bluebell arises from a white bulb the size of a small tomato, and produces a rosette of spear-like leaves and a single flower spike; none is much taller than your forearm. It takes hundreds to make a splash of colour. The bells hang down in a line along the raceme in a single graceful curve. ‘Raceme’ is scientifically correct, of course, but how I wish that we could refer to it as a ‘chime’. Flowers at the base of the spike open first, their six delicate petals curving backward to form a skirt that curves away from the creamy anthers; it takes a while for the whole display to be over, as each flower up the spike comes to perfection one after another. With a natural variation in flowering times according to aspect and local climate, there are a few woodland nooks where bluebells open up precociously, and others where they linger longer. But wherever they bloom, theirs is a short-lived glory; and only when they are seen in numbers can the delicate perfume they produce be appreciated. As they generally reproduce from a slow multiplication of their bulbs, rather than from seed, the masses of English bluebells seen in our woods are a reliable indicator that they are of ancient origin. Hence it is likely that the flowers that delight my eyes today have been admired for centuries from the same spot near the edge of this very wood. The temptation is to pick a great bunch of blooms, but in a vase they lose vibrancy; they need a myriad companions to assert their natural magnificence. A thrush singing in mellow, repetitive phrases from deep within a holly bush adds some sort of blessing.

This is our own piece of classic English beech woodland, gifted with bluebells, covered with trees for generations, and changing at the slow pace of sap rising and falling. When Lambridge Wood was subdivided by the previous owner our little piece of it was arbitrarily christened Grim’s Dyke Wood, after the ancient monument that passes through the wood. The new name added an irresistible whiff of romance to the sales pitch that helped us to part with our money. It is a triangular plot with nearly equal sides, two of them marked out by public footpaths. We access the north-east corner of the triangle by vehicle along a track through Lambridge Wood that leads to a converted barn adjacent to our piece of woodland; the barn has a picturesque cottage next door that will also feature in this book. On the ground, it is hard to detect a very gentle slope of the whole plot to the south, but the incline is enough to admit a magical influx of winter light in the afternoon with the setting sun. About four acres (1.6 hectares) of woodland is not exactly a vast tract of forest, but it is enough to include more than 180 mature beech trees, which I counted, and bluebells galore, which I didn’t.

Lambridge Wood sits high in the Chiltern Hills, thirty-five miles to the west of London, near the southern tip of the county of Oxfordshire. Although so near the capital, the wood could be ten times further away from it and would not gain a jot more feeling of remoteness. As I contemplate the bluebells only the occasional growl overhead from aeroplanes bound for Heathrow reminds me that there is a great urban sprawl so close to hand.

The Chiltern Hills form the high ground for a length of more than fifty miles north-west of London. They follow the course of the outcrop of the pure white limestone known as the Chalk.3 The same rock makes the white cliffs of Dover, where England most closely approaches continental Europe; the sight of the cliffs has brought a lump into the throat of many a returning traveller, so it might be thought of as a peculiarly English rock, although it is actually widely spread around the world. As limestone goes, it is a very soft example of its kind – one that can be flaked with a penknife. Even so, it is harder and more homogeneous than the rocks that underlie it to the north, or overlie it in the direction of London, and differential weathering and erosion over hundreds of millennia has promoted the relative recession of the softer rocks to either side. The Chilterns stand proud.

The scarp slope along the northerly edge of the hills is surprisingly steep, and from the top of the Oxfordshire segment there are fine long views across the Vale of Aylesbury towards Oxford in the distance. That scarp lies only ten miles north-west of our wood. Half that distance away, Windmill Hill at Nettlebed is one of the highest points in southern England at 692 feet (211 metres) above sea level.4 The tops of the Chiltern Hills are richly wooded compared with the intensively farmed lowlands on the gentle plain to the north, where a patchwork of neat green fields or brown ploughed farmland is the rule. Google Earth or the Ordnance Survey map reveal much the same pattern, whether seen from above or in plan. The high ground has long fostered special pastoral practices, in which woods played a continuous and important part in the rhythm of country life. That is why they have survived. Our tiny patch is just one small piece of a larger tapestry stitched together from irregular swatches of trees, stretching over many miles. Other kinds of farmland are interspersed, to be sure, and in some places there has been sufficient clearance for open downland. But near our patch, copse, shaw, hanger and wood dominate the landscape.

When I first walked through Lambridge Wood as a newcomer to the Chiltern Hills I was overwhelmed by a feeling of entering a realm of eternal nature. Here was the antidote to jaded city life. The woods are unchanging; they help to put our small concerns into perspective. They are restorative, havens for animals and plants; safe places for the spirit. Such a perspective drenches Edward Thomas’s rapt accounts of woodland in The South Country, and has a modern mirror in Roger Deakin’s Wildwood nearly a century later. Here is the farmer A.G. Street writing in 1933 after listing more than one disappointment of middle age: ‘The majesty of the wood remains unaltered. As I wandered slowly through it, the terrific importance of my trouble seemed to fade away. The peace of the wood and the comfort of the still trees soon iron out the creases in my soul.’5 Surely some comparable emotion lay behind the enthusiasm with which we purchased Grim’s Dyke Wood, our own piece of peace. It was a romantic (or even Romantic) notion, and not wrong in its essentials. But, as Henry David Thoreau remarked of the English poets: ‘There is plenty of genial love of Nature but not so much of Nature herself.’6 The wood has indeed given much pleasure, but much of that delight proves to be an intimate examination of nature close to. And I now know that the history of nature is not only natural history. The wood is not eternal – it is a construct, a human product. It was made by our ancestors, modified repeatedly, nearly obliterated, rescued by industry, forgotten and remembered by turn. The animals and plants rubbed along with history as best they could, mostly unconsidered except as meat, fuel and forage: the natural history was part and parcel of the human history. The result is what we see today. Romantic empathy with ‘Nature’ is all very well, but it does have to brush up against the hard grit of history, which can soon polish off any coating of wishful thinking.

So this book is both romantic and forensic, if such a combination is possible. My diary records the status of the beech trees and the animals and plants, the play of the light, the passage of the seasons, expeditions and people, and the incomparable pleasures of discovery. I have also taken samples from the wood to the laboratory to dissect under a microscope. I have invited help from experts to identify tiny animals – mostly insects – about which I know little. Add to this excursions into historical literature and archives, and much time spent scrutinising scratchy ancient maps, deeds and sales catalogues to understand how the wood fared under management for profit or pleasure, and its place in the economy of estate, county and country. I have interviewed those who have known the woods during long lives. There will be a little geology, and more than a touch of archaeology.

Several of my previous books have dealt with big themes: the history of life or the geology of the world refracted through a personal lens. This book is the other way round: a tiny morsel of a historic land looked at all ways. The sum of all my observations will lead to an understanding of biodiversity – the variety of animals, plants and fungi that share this small wood. Biodiversity does not just belong to tropical rainforests or coral reefs. Almost every habitat has its own rich assemblage of organisms competing, collaborating and connected. What is found today is the result of climate, habitat, pollution or lack of it, history and husbandry. For me, the poetry of the wood derives from close examination as much as from synthesis and sensibility. But I am aware that description alone does not necessarily lead to understanding. This example from what may be Wordsworth’s worst poem (‘The Thorn’) comes to mind:

And to the left, three yards beyond,

You see a little muddy pond

Of water – never dry

I measured it from side to side:

’Twas four feet long, and three feet wide.

The Darwin connection

Despite this dire topographic warning, I must describe the anatomy of the countryside around the wood, since it is crucial to this history. Grim’s Dyke (and Lambridge) Wood lies at the top of a locally high ridge, and immediately to the north of it a steep slope runs away continuously downwards to a rather busy road; that part of the incline below the barn has been cleared of trees, and is now occupied by a well-fenced deer park. The main road is partly a dual carriageway running westwards up a typical Chiltern dry valley and serves to connect the nearby small and historic town of Henley-on-Thames, where I live, with the larger and even more historic town of Wallingford thirteen miles away. Wallingford also lies adjacent to the Thames, but between it and Henley the great river takes an enormous southerly bend by way of big, bustling Reading, as if reluctant to breach the barrier of the Chiltern Hills. This it finally does – and most picturesquely – near the village of Goring, about seven miles from Wallingford, where the Chalk cliffs are steep enough on the eastern side of the floodplain to suggest a gorge. Geographers have more prosaically called it ‘the Goring Gap’. Robert Gibbings is the most charming writer on this and other stretches of the Thames.7 I doubt I can live up to his blend of precise natural history with human observations of all kinds. The journey across country between Henley and Wallingford is very much shorter than the distance along the river, a fact that profoundly influenced the development of medieval Henley and its surroundings, including our small wood. Henley played an important part in the transport of goods and people between London and Oxford, and its story is inextricably bound up with that of the River Thames.

There are other ways to locate our wood within the English countryside. Ancient England is a curiously tessellated collage of different patterns of ownership and responsibility. Parish, village and manor all make different claims. Grim’s Dyke Wood lies near the edge of the old ecclesiastical parish of Henley-on-Thames, so its original church, as it were, is the fine, thirteenth-century flint-and-stone edifice of St Mary’s in the centre of town two miles away.8 On the way out of Henley in the direction of Wallingford and Oxford the road is dead straight and splendidly bordered with wide grass verges and avenues of trees. This is the Fair Mile, appropriately named, and the ecclesiastical parish extends out in this direction. At the end of the Fair Mile, a minor road forks off to the right along another valley to Stonor, while the main road continues uphill towards Nettlebed and Wallingford. At this point our wood lies at the top of the slope on the skyline to the left (and south). The fork in the road marks the end of the village of Lower Assendon, and is very near to the wood as the red kite flies, which it frequently does around here. Smoke from Assendon chimneys can be smelled in the wood. Assendon also houses the Golden Ball, the closest pub, which seems nearly as ancient as the hills, and is reached by a steep downhill scramble along a path descending from Lambridge Wood. At the top of the hill, and further away from Lambridge, another ancient village with the briefest possible name – Bix – is arranged around a huge common, and is in a different parish.

But more important to our story than either parish or village is the manor. For most of its recorded history Lambridge Wood, including our piece of it, has been part of the manor of Greys. The manor house, Greys Court, is a remarkable survivor, just a mile away from Grim’s Dyke Wood. Both the house and the estate are now managed by the National Trust, and thousands of visitors flock there. These benign crowds of pensioners and picnickers arriving by car make it difficult to imagine the house as a remote backwater, but there was a time when the Chiltern Hills were wild and inaccessible. Criminals could go to ground there; religious dissenters could hide there. Greys Court still commands the least urban aspect in the Home Counties. From the garden lawn the modern road is hardly visible, and the view is dominated by a broad, clear valley dotted with sheep and flanked on either side by dense beech woods. It could still be a landscape through which horses provided the only transport, at a time when London belonged to another world.

Although substantial, Greys Court could hardly be described as a stately home. Part twelfth-century fortified castle, and part Tudor mansion, it remained in private hands from medieval times until 1969. In a brick outhouse an extraordinarily ancient donkey wheel resembling some cock-eyed wooden fairground attraction was used until the twentieth century to lift water from a well excavated deep down into the chalk. It is not difficult to imagine how a place like Greys Court might roll with the blows of history, battening down at times of hardship, fattening up in times of plenty. The extensive estate could provide what was needed: sufficient arable land for wheat and barley, pasture for cattle and sheep, from the beech stands fuel and wild game, and good water from the well. Lambridge Wood lay along the northern edge of the estate. Land nearer the big house was more likely to come under cultivation, so the marginal position of the wood doubtless contributed to its long-term survival. It was always useful just where it was.

The parish church for Greys Court, where the grand names belonging to the big house are interred, is a tiny, flint construction with a low tower, close by the road in Rotherfield Greys, a hamlet that also has the second-nearest pub to our wood, the Maltsters Arms. Church and pub can be reached from the wood on public footpaths leading southwards and crossing open fields for a little more than a mile. I have never met anyone else on these old rights of way. The paths that run along the River Thames just a couple of miles away are crowded with walkers, but the open Chilterns are still the province of the skylark and the stroller. On a clear spring day, the low hills conceal endless possibilities, all of them joyous. The Maltsters Arms is one of those cosy pubs with exposed oak beams on low ceilings, real fires, no background music, and a landlord who actually seems to like his customers.

The church is next to the pub, as tradition demands. A large chunk of its interior is taken up by a side chapel devoted to the monuments of the masters and mistresses of Greys Court, and principal among these is the exuberant and splendid alabaster and marble tomb of Sir Francis Knollys (d.1596) and Katherine, his wife. Their effigies lie side by side praying in formal splendour, while around the tomb seven sons and seven daughters parade in a pious line. Most touching is a tiny baby who died in infancy, whose effigy lies alongside that of his father. Sir Francis was a noted courtier of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. I like the thought that on his days away from court Sir Francis may have wandered in our wood for pleasure, or maybe hunted game there. On the floor of the nave a brass to Robert de Grey (d.1388) is altogether more modest, even though the manor and church both bear his name. Clad partly in chain mail, his sword by his side, and gauntlets still frozen in metallic prayer, he seems more a grand cipher than a real person.

In the countryside, for many centuries manors and estates were paramount. Those who owned the estates neighbouring Greys provided its society. These nearby manors suffered the same pestilences and plagues, and shared good years and bad. The lords and gentry knew one another, and paid formal and informal visits. They eventually became what my mother would have termed ‘county’. From time to time the estates were home to remarkable historical figures; at others their occupants were quietly obscure. The status of peasantry and servants and artisans changed gradually, but all the estates had to absorb the changes, which continue today. The closest estate to our wood – and Greys manor – was Fawley Court and Henley Park to the north: a pigeon could fly from Grim’s Dyke Wood into the Park in a minute. To the east lay Badgemore. The fine house has now vanished, and what remains of it is a golf club. While further still to the north a small and perfectly set stately home remains in its own valley; the Stonor family that lives there boasts more than eight hundred years of occupancy, and one of the longest continuous lineages in Great Britain.

Another map ties the wood more closely with Rotherfield Greys than with Henley-on-Thames. Civil parishes are the basic unit of local government, and frequently do not have the same boundaries as the ancient ecclesiastical parishes. They elect councillors, not priests, and their boundaries were sorted out at the end of the nineteenth century to make a more sensible system of local administration. Our wood lies in the civil parish of Rotherfield Greys, even though it is ecclesiastically Henley; this is appropriate to its other links with the big house. It seems that Lambridge Wood was always on the edge of some map or parish or village, which may be a good place to be to pass unnoticed. And like many other woodlands, our wood was also free from tithes: a 10 per cent levy on the income derived from the land once provided the principal source of income to support the local church. Following an Act of Parliament in 1836 a schedule of tithes was compiled across England, and in the Oxfordshire Record Office a map of 18409 portrays Lambridge Wood with considerable accuracy. The accompanying ledger prepared by a clerk in best copperplate script declares it ‘exempt’. I occasionally put a pound coin in the box at Rotherfield Greys as a token of expiation.

In 1922 Lambridge Wood was sold off from the Greys estate after a history stretching back to Domesday. We have the map detailing ‘Lambridge Farm and 160 acres of woodland’ which was sold in Henley Town Hall on 26 July to George Shorland, a rich farmer and entrepreneur who had purchased land all around Henley. The modern era of Lambridge Wood had begun, and the unbroken thread leading back to medieval times had been severed. We will meet some of the subsequent owners later on, but now I am going to take a jump to 1969, when Lambridge Wood passed into the ownership of Sir Thomas Erasmus Barlow, Bt, whose heirs owned it until as recently as 2010. I admit that the name meant nothing to me. Sir Thomas was the third baronet to carry the title, and a distinguished naval commander. In a fairly perfunctory way, I started one of those online searches that have become routine for writers, as they have for almost everybody else. I moved backwards in time as far as I could. The First Baronet, another Thomas, had been Queen Victoria’s private physician, a man who died dripping with honours, and no doubt had an outstanding bedside manner. The Second Baronet, Sir Alan Barlow, father of Thomas Erasmus, was scarcely less distinguished as a civil servant in the grand tradition, serving as Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald’s Principal Private Secretary from 1933 to 1934. But then I discovered something that caused the mouse to freeze in my fist. Alan Barlow had married Nora Darwin. A magical name had somehow found its way into the genealogy of the wood. If one thread had been severed, another had been established. It did not take much more research to establish that Nora was the granddaughter of Charles Darwin. So our wood, the subject of my own modest natural history investigations, had recently belonged to a direct descendant of the greatest natural historian of all time.

I happen to know another direct Darwin descendant who worked with me at the Natural History Museum, the botanist Sarah Darwin. The Darwins are an unusually distinguished clan, and the present generation respects the ramifications of the dynasty. Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus sired one of those lineages that seem to have done nothing but good in the world: the third Sir Thomas’s middle name must have been a nod in the direction of the grand old progenitor. Sarah knows the current baronet, Sir James Barlow; not least, they are both Ambassadors for the Galapagos Conservation Trust, which seeks to protect the world’s most famous natural evolutionary laboratory from further damage through foolish exploitation. In the autumn of 2014 Sarah introduced me to Sir James and his sister Monica. I met them both in our wood, and together we traced a path through Lambridge that they had not done for many years. James remembered his grandmother, who, he said, had been dandled on Darwin’s knee. So there I was, talking to somebody whose grandmother might have giggled and snuggled into the breast of the incomparable naturalist. I know that a number of generations back we are all related somehow – it is just a matter of statistics – but none of my friends or colleagues (apart from Sarah) has any direct link with Charles Darwin. It is difficult not to see this connection as a kind of blessing for the project – in the most secular meaning of that word, of course.

As we ambled through Lambridge Wood James and Monica explained that their father had been very much the conservationist until his death in 2003. Some parts of the wood (not ours) had been clear felled in rectangular plots, and replanted with conifers, mostly larch and Corsican pine. These are not natural trees to find in the Chiltern Hills; on the aerial view they show up as intensely dark-green areas quite distinct from the undulating beech crowns. The intention was to harvest the mature larch for pit props, but that project was evidently ill-conceived, since the Barlow ownership of the wood coincided almost exactly with the terminal decline of coalmining in Great Britain. Now, some of our fellow small wood owners are simply removing the larch to allow the broadleaved forest to recover. There is a great pile of conifer offcuts near the entrance to our wood; I decided to leave these fragments of mistaken forestry in order to study the processes of decay.

Elsewhere, the beech wood seems to have been left quietly to get on with being a beech wood, helped by periodic thinning. The manager of the wood was John Mooney, and the Barlows told me that they knew him as ‘Eeyore’ because of his pessimistic prognostications for making any money out of the wood. His annual accounts always finished with a thumping loss. It is as well that Barlow senior was primarily interested in good ecological stewardship, for all his correspondence from Mr Mooney is steeped in wry gloom.10 The wood was under threat from trespassers, he said, or horse riders who cut barbed-wire fences, and poachers who poached. Deer of all species curtailed almost all regeneration, and what little was left was damaged by squirrels. The whole business was hamstrung by interfering busybodies and/or charlatans from the Campaign for the Preservation of Rural England and official bodies like English Nature. In 2000 his annual summary finished magisterially: ‘It has been getting progressively worse for the past 25 years [before] hitting this nadir.’

Then Harry Potter came to the rescue. From 2001 onwards J.K. Rowling’s novels about the young wizard were adapted for the screen, and the movies were watched by countless children. Many of them wanted their very own broomstick so they could play quidditch and generally fly about the place. The heads of the broomsticks were made from bound bundles of twigs, and the right kinds of twiggy shoots could easily be cut from birch trees and regenerating stumps in Lambridge Wood. More than a century ago there was an artisan known as a ‘broom squire’ who plied his trade deep in the beech woods, so it was a traditional skill.11 Now there was an unprecedented broom boom, a besom bonanza. James Barlow said that they couldn’t supply enough to the toy trade. In the end Lambridge Wood as a whole made at least a little money, in a thoroughly ecologically respectable way.

The distribution of trees today in our patch of Grim’s Dyke Wood is likely to have been much the same when Sir Thomas bought the whole woodland, except that the beeches have had another forty years or so to increase their girth and height. Mr Mooney recorded that the wood escaped comparatively lightly from the great storm of October 1987, which flattened whole woods elsewhere (it didn’t cheer him up). Many of the beeches are between ten and twenty paces apart, close enough to provide total leaf cover in summer, although there are several small clearings, and a large one on the northern edge where felling must have been more recent. Although beech is dominant, other kinds of woodland trees are a delightful addition to the silviculture. Eighteen magnificent wild cherry trees shoot skyward on sheer trunks to the same height as the beeches. Three stately ash trees decked in yellowish bark have spawned uncountable numbers of offspring. Less noticeable are wych elms discreetly hiding among the beeches. We have a total of just two oak trees, one of them a fine specimen, the other something of a poor relation, both tall. The same number of yew trees are the only conifers in our wood; these two are just at the beginning of their long, long lives. I scratched around for hours among brambles before finding a solitary field maple, and a tiny youngster at that, but I am glad to have it in my inventory.

Then there is the understory: trees of lesser stature that will grow happily in the shade of their towering neighbours. The most obvious is plentiful dark-green holly – probably too much holly. Still, I welcome it where its prickly evergreen foliage makes an almost impenetrable screen twice as high as a man around my favourite part of the wood: the Dingley Dell. Not quite in the middle of our patch, the Dell surrounds two of our most impressive old beech trees, which have been christened the King and the Queen. Unlike many of our beeches they don’t soar away upwards immediately; there is a little spread of branches. Beneath these giants the ground is clear except for a covering of old leaves. Sitting on a log there in the April sunshine I feel as content as a dog before a fire. It is a place to write up my notes, and eat bacon sandwiches. Around the Dingley Dell a few old coppices of hazel – a traditional Chiltern undercrop – produce clusters of long, unbranched trunks almost straight from near the ground; these are of several ages and hence variable thickness. Some of the branches are dead – they need attention. A couple of young birch trees are growing on the edge of the large clearing. All these tree species have become old friends, and like all my friends they have quirks and history and several failings. We shall get to know them all.

Cherry blossom

During April the wild cherry blooms at the same time as the bluebells, but the cherry flowers are displaying high in the canopy. In hand I examine a flower head that has fallen down from above: coppery young leaves, half a dozen at the tip of the shoot all pointy and enthusiastic as if they should cry, ‘Forward, forward!’ But then behind this tip is a natural flower arrangement – ten little bundles of white cherry blossom coming off a grey-brown stick. They are arranged in clusters of four or five blooms, each one held on a green ‘matchstick’ an inch long. Every flower carries five notched, almost perfectly white petals surrounding yellow stamens, which are tiny threads with spherical heads like miniature pins (and in the centre of the flower, hardly grander, the style and stigma). Five red-brown sepals bend backwards from the flower as if to feign deference to the performance going on in front, which might be described as a cluster of tutus; and each bunch of flowers emerges from another five-fold arrangement of bracts next to the stem. So the twig is a series of bouquets topped by a flourish of leaves, a brief, exuberant festival of white blossom fifty feet above the common view. An early feast for insects, I suppose. Why do we need those double garden varieties of flowering cherry – ‘flore pleno’ and the rest? Admittedly they do augment the resemblance of the flowers to tutus, but there is already enough in the solitary blossoms. A Japanese artist might lose himself in a flower or ten: so short-lived, so fragile, like rice paper crimped into snowflakes. Even now a gentle snowfall of petals tumbling from high above is settling on last year’s old beech leaves; in an hour or two the sun will have frizzled them into obscurity.

Butterflies appear suddenly in some numbers, and not just the umber-brown speckled wood butterflies, flitting erratically like camouflaged and subtle ghosts in and out of the shade, but also brimstone butterflies as bright and freshly coloured as primrose flowers. These last arrivals almost make up for the absence of real primroses in the wood, for the iconic springtime flower does not deign to live in the sparse, poor soil of Lambridge (this saddens me, as Darwin worked on primroses). A solitary peacock butterfly, a battered survivor of the winter frosts, with eyed wings shredded at their margins, is sunning itself on a bramble in the clearing, the better to gather the energy for a final burst of egg-laying. A green-veined white lingers for a second, then flits past and away.

I have evidently become attuned to the Class Insecta. In the midst of the bluebell sea, open flowers are pollinated by large bumblebees that delicately hang off pendent blossoms that look too frail to carry them. I fancy they are like oversize clappers hanging off the bells. I believe I can recognise the white-tailed (Bombus lucorum) and red-tailed (Bombus lapidarius) species, not least because they have a convenient dab of the appropriate colour at the end of their fuzzy abdomens. A huge red-tailed bumblebee must be a queen on the search for an old mousehole in which to establish a new colony. She buzzes about the cherry roots, and she won’t have long to wait to find a suitable site. While I am crouching among the bulbs, a ‘pretend’ bumblebee whizzes past me that I know to be the bee fly (Bombilius major), one of nature’s cruel deceivers. Although fuzzy and generally bee-like, it is no bee at all (it is closer to a bluebottle). It carries a long proboscis at its head end, and I watch it dart forward into and back out of a flower to feed on nectar, so it really is an entomological humming bird as much as anything. But it reproduces by laying its eggs near a true bees’ colony, and its larvae crawl into the ‘nest’ where they consume the bees’ grubs. In fact, it is an entomological Iago. I recall that Darwin described how deception was commonplace in nature; the man himself apparently so free of duplicity.

This is the day when all the male birds sing out passionately for a mate. Their plumage is buffed and preened, spring-ready. I am an amateur at birdsong, but I cannot mistake the sweet and penetrating phrase of the song thrush, repeated thrice or so, as if to emphasise its originality, for the next phrase is always different, and always repeated in its turn. I can pick out the implausibly loud song of the tiny jenny wren with a little rattle at the end of its performance. The songs of the robin redbreast and the blackbird I know well from my own garden. But I would not have recognised the nuthatch’s broadcast had I not seen the handsome blue-backed bird sing from a bare twig: a kind of ‘pwee-pwee-pwee’ – simple and penetrating. Can it be that there is an inverse relationship between the showiness of the plumage and the beauty of the song? The nightingale and the most musical of the warblers are pretty ordinary of feather, while the extravagant peacock’s raucous cry appeals only to other peacocks and the English aristocracy. Somewhere in the middle of this aesthetic spectrum, black-yellow-green great tits are everywhere in the wood uttering their repeated high regular notes – ‘tee-too’, possibly – which is hardly spectacular. The more sibilant, guttural, chatty conversation of the blue tit is more appropriate for such a small and bouncy cheeky chappie. Just now many blue tits hop rapidly about the denser branches whistling to one another, ‘Here we are!’ What I cannot do (pace the nuthatch) is reliably locate the source of all the birdsong; it seems to emanate in a general and celebratory way from almost everywhere. I begin to understand those descriptions of whole woods ‘bursting into song’. The distant drumming of a woodpecker, a sporadic, hollow-sounding percussion, provides all that is needed for a backbeat to the avian orchestra. But then I briefly catch a glimpse of a timid tree creeper dodging behind a beech trunk, almost furtively working its way rapidly up the tree in search of insects tucked into tiny crannies in the bark that it can pick out with its curved bill. It moves in silence.

One cry is at odds with the general vernal celebration – a kind of wheezy, cross-sounding phrase repeated irregularly. Our pair of woodland buzzards are wheeling and gliding slowly round and round high overhead, as if barred from the general celebration below. Theirs is a simple call, almost like that of a baby working up to something more exciting. I had seen them yesterday flying through the wood itself: weighty, serious birds that appeared too substantial to negotiate their flightpath between the trees, something they nevertheless did with aplomb. Lambridge Wood is their patch. Beware, small rodents and unwary birds! If it turns out to be a good year for them, it will be a good year for the buzzards too.

Among the bluebells my eye is taken by something much more turquoise: a thrush’s egg lying on the ground. It looks so perfect at first glance; a Mediterranean-summer blue overlaid with just a few black dots. I then remark a ragged hole in one side – somebody has taken it from its clay-lined nest and consumed the contents. The buzzards are exonerated (too much of the egg survives); I suspect a grey squirrel. I cradle the empty shell in the middle of my palm. It is almost impossibly light. Surely this must be the first item for my wood collection; I must cherish it.

And then my eye is caught by a perfectly white bluebell, just one among so many thousands of the common kind. I suppose it should be called a whitebell. It is as rare as a sober Irishman on St Patrick’s Day, but much more conspicuous. It stands out from the crowd, visible yards away. It is the result of a natural mutation. If it were a successful mutation I suppose there would be many more of them, but there it is, living proof of that molecular part of the science of evolution that Charles Darwin did not know about. Just one tiny change on the DNA code and blue becomes white. Since most bluebell reproduction is from the proliferation of the bulbs, if I had a mind I could lift this example, nurture it in my garden, and artificially ensure its success. I could call it variety ‘Grim’s Dyke’. The origin of so many white garden flowers is thus revealed: white campanulas, that are so blue in the hedgerows; white pinks (never, after all, ‘pink whites’); white honesty; even white pelargoniums. Like the wild cherry, some are born white; others have whiteness thrust upon them.

Ground elder soup

The first ground elder shoots (Aegopodium podagraria) are prolific near the edge of the wood. This plant is a notorious garden weed that, once established, is almost impossible to eradicate from the herbaceous border, but in a wood it makes a prettier sight and a more constrained patch. Its lobed and divided leaves appear well before parsley-like flowers. When the leaves are young and pale green, I discovered that they are a good vegetable; they become rank a month later. So there is a different way to view ground elder: as food! Ground elder soup is simple to make. A bagful of young leaves is gathered easily enough. The coarser stalks must be broken off, and the leaves are roughly chopped. A finely-sliced onion is softened by frying in butter, until it just starts to caramelise. At this point a medium-sized floury potato is added, chopped into small cubes, and placed with the leaves and onion in a heavy pot, and then a generous quantity of stock (or 1½ to two pints of water and a chicken or vegetable stock cube) together with a pinch of mixed herbs and pepper to taste. After it has been brought to the boil it is simply a matter of simmering over a low heat until the potato is soft, when the whole can be blended in a liquidiser. Croutons or a swirl of cream add a finishing touch. I should say that there are other wild members of the parsley family that are poisonous, most particularly hemlock. There should be no risk of mistaking the feathery leaves of hemlock for the rose-like leaves of ground elder, but if in doubt leave well alone.