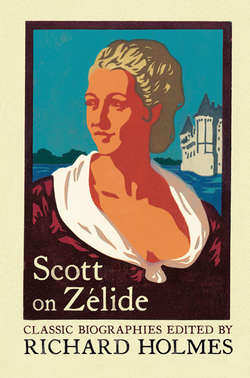

Читать книгу Scott on Zélide: Portrait of Zélide by Geoffrey Scott - Richard Holmes - Страница 7

3

ОглавлениеIn her remarkable summer letter of July 1764, Zélide set out two possible and radically different directions for her life. What she is most concerned about – this young woman of the European Enlightenment – is sexual happiness and intellectual fulfillment. The two do not necessarily coincide. She puts two alternatives before the Chevalier d’Hermenches.

First, she could be an independent woman. She could model herself on the celebrated Parisian wit and beauty Ninon de Lenclos, live a self-sufficient life in a city (Amsterdam, Geneva, London or Paris are all considered), take lovers as it pleased her, write books, keep a literary salon, and develop a circle of trusted and intimate friends. Or second, she could be a married woman. In this role, not at all to be despised, she could fulfil the wishes of her parents, make a good aristocratic marriage to ‘a man of character’, find emotional security in her family, have children, and look after a large country estate in Holland. This too could be immensely fulfilling, provided only that she found a truly loving and intelligent husband, who ‘valued her affections’, who ‘concerned himself with pleasing her’, and above all, who did not bore her.

‘You may judge of my desires and distastes,’ she wrote to the Chevalier d’Hermenches. ‘If I had neither a father nor a mother I would be a Ninon, perhaps – but being more fastidious and more faithful than she, I would not have quite so manylovers. Indeed if the first one was truly lovable, I think I might not change at all…’

This possibility sounds like Zélide setting her cap at the Chevalier, a thing that she would often contrive. But perhaps she was not entirely serious? She continued: ‘But I have a father and mother: I do not want to cause their deaths or poison their lives. So I will not be a Ninon; I would like to be the wife of a man of character – a faithful and virtuous wife – but for that, I must love and be loved.’

But then, was Zélide entirely serious about marriage either? ‘When I ask myself whether – supposing I didn’t much love my husband – whether I would love no other man; whether the idea of duty, of marriage vows, would hold up against passion, opportunity, a hot summer night…I blush at my response!’ Here was the premonition of the choice that has faced so many modern women since: career or marriage, freedom or faithfulness.

The extraordinary fascination of Zélide’s life story lies in how this choice worked out in practice, over the next forty years. It was not, of course, by any means as she had planned it. She did marry and settle on a country estate, but she never had children and she was desperately lonely for much of her life. Equally she did write books, notably the exquisitely observed social comedy Mistress Henley (1784), the influential and tragic love story Caliste (1788) and the proto-feminist novel Three Women (1795). And she did have her hot summer nights. But she was intellectually isolated, and ended by pouring much of her emotional life into letter-writing. The great social changes of the French Revolution came too late to save her. After her death in 1805, at the age of sixty-five, her books and her story were soon apparently forgotten.