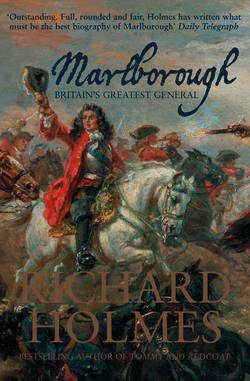

Читать книгу Marlborough: Britain’s Greatest General - Richard Holmes - Страница 8

Portraits in a Gallery

ОглавлениеWe can get much closer to our quarry in words than we ever can in pictures. Portraits often deceive, and it is perhaps in the early eighteenth century that the deception is most complete. There are the great men of the age, with well-scrubbed pink-and-white faces, staring complacently at their world from beneath full-bottomed wigs, lips pursed in the half-smile of those who know that life has treated them well. The peruke’s soft curls and the snowy lace of a jabot tumble onto a coat whose stuff and hue betokens the wearer’s status: a cleric’s black broadcloth, a merchant’s prosperous blue or plum, or a soldier’s martial red. Peers often wear the ermine of their House, with a coronet denoting their rank (six silver balls on a plain silver gilt circlet for a baron, and on to the chased coronet with its eight strawberry leaves for a duke) dangling from the noble fingers or tossed onto a table just within the picture’s frame. In their portraits generals appear in the armour they would never have worn on the battlefield, sometimes with a plumed helmet, as useless then as a general’s ivory-hilted dress sword is today, standing in for a peer’s coronet.

Women are plump-faced, opulent of bust and shoulders, and usually portrayed with their heads tilted ever so slightly to the right to allow the artist to throw some shadow beneath a soft jawline. Children are rarely allowed much in the way of childhood. Once boys had been breeched, at the age of four or five, they appeared as miniature adults. Johann Baptiste Clostermann’s huge family portrait of the Marlboroughs, painted in about 1694, shows the parents and their five children against theatrical drapes. John, later Marquess of Blandford, their eldest son, is stepping up onto the dais, looking back at the artist and gesturing proudly towards his elegant family. He was nine years old at the time.

A year later Nicholas de Largillière painted James II’s only legitimate son, James Francis Edward Stuart (‘the Old Pretender’) and his sister Louisa Maria Theresa. Although the young prince was only seven and his sister just three, both are dressed for court: James is wearing long coat, lace jabot and silk stockings, and Louisa has a dress with a train and the tall fontange headdress. William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, was the only one of Queen Anne’s many children to live beyond infancy, and was regarded by many as the heir most likely to prevent the restoration of his uncle James II. In 1699 Sir Godfrey Kneller painted him as a warrior prince, with a soldier’s cuirass: the boy was ten years old and had just a year to live.

There is enough symbolism to keep costume historians busily engaged for years. Gentlemen advertise their status by wearing swords, the slim, straight-bladed small sword in town and the stubbier hunting sword in the country. Races at Newmarket, then the only major national meeting, were an exception, for folk of all classes met on equal terms, turning out ‘suitable to the humour and design of the place for horse sports’, with nobody wearing swords. Spurs were important even if there was no evidence of a horse, for they showed that although the sitter might not be riding at the time, he could vault into the saddle at a moment’s notice. Not for nothing did the Latin inscriptions on gentry’s tombstones style a knight as equitus and a gentleman as armiger. In Charles II’s time red shoe-heels – a fashion borrowed, like so much else, from France – suggested noble rank, and the fashion spread so that officers of the Restoration army were as identifiable by their bright heels as their great-grandsons were to be by their epaulettes. The greatest officers of state, like the lord treasurer and secretary of state, carried thin white staffs of office. Sidney, Earl Godolphin, had his made short enough to be carried in a sedan chair, while the Earl of Rochester had his, of the longer variety, carried by a bareheaded footman to allay any doubts about the distinction of his chair’s occupant.

A portrait of Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough painted in about 1700 had a gold key added to its waist in 1702. In the interim Sarah had become keeper of the privy purse to the new queen, Anne, and the key confirms the status that her expression already suggests: she is a woman whose beauty is matched, at last, by her wealth and influence. And so pigment is splashed across canvas. Mouths curve like cupid’s bow, dogs stare admiringly at masters, steeds curvet without apparent inconvenience to riders, and occasionally, like extras in a drama, lesser mortals gather slain game or ply musket and bayonet amidst the background smoke.

None of this is a great deal of help to historians. Even court artists in England, it is true, could rarely disguise that bulbous blue-eyed, faintly irascible expression that characterised the Hanoverians, any more than their colleagues in Vienna could do much with the Hapsburg jaw. However, artists seldom get us beyond polite generalities. Portraits of Prince Eugène of Savoy-Carignan, Marlborough’s great collaborator, give no real sense that he was widely regarded as one of the ugliest men of his age, and almost always had his mouth slightly open. Louis XIV, for all his sneer of cold command, was five feet five inches tall, a full five inches taller than Charles I but an inch and a half shorter than William of Orange – who was four inches shorter than his wife Mary. William himself was, if you will forgive the phrase, no oil painting: he was thin and somewhat hunchbacked, and his face, already striving to accommodate a prominent nose, was heavily pockmarked.

While artists were happy enough to use their skills to reflect status and lineage and to hint at accomplishments and aspirations, in the main they present us with a great number of plump-faced, well-to-do gentlemen in wigs, accompanied by ladies perhaps too generously built for modern taste. Charles II’s mistresses were generally Junoesque but pretty, while James II’s were as substantial, but so very, very plain that Charles quipped that they had been imposed upon his brother by his confessor as a penance. Sir Peter Lely’s portraits, however, make them look so alike that even contemporaries complained:

Sir Peter Lely when he had painted the Duchess of Cleveland’s picture, he put something of Cleveland’s face as her languishing eyes into every picture, so that all his pictures had an air of one another, and the eyes were sleepy alike. So that Mr Walker the painter said Lely’s pictures were all brothers and sisters.27