Читать книгу Dr Johnson and Mr Savage - Richard Holmes - Страница 10

Chapter 3 Night

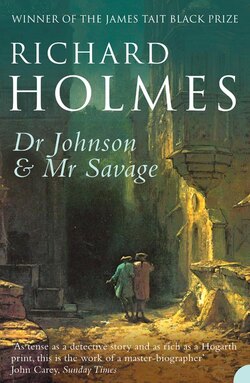

ОглавлениеThere has always been one vivid, popular legend of Johnson’s unlikely friendship. It is enshrined in a particular anecdote that was passed lovingly around Johnson’s later circle: each one heard, embroidered and retold a different version of it. The account describes how Johnson and Savage walked round the squares of London all one night, being too poor to afford either food or lodging but sustained by the passionate intimacy of their conversation.

This story, in its various renditions, became symbolic of the Augustan writer’s life in Grub Street, just as the story of Thomas Chatterton’s death in a Holborn garret became symbolic of the romantic poet for the later eighteenth century. It passed quickly into treasured anecdote, and remains to this day the one clear image of young Johnson in London. A recent American scholar summarises it with relish: ‘Those who know nothing else of his early life can envision in Hogarthian detail Johnson in his ill-fitting great-coat and Savage dressed like a decayed dandy, wandering the street for want of a lodging and inveighing against fortune and the Prime Minister.’1

It is easy to see why the story appealed. It is indeed like a Hogarth illustration to Johnson’s famous line, from his poem London, ‘Slow rises worth, by Poverty depressed’. The link between poverty and genius, between poetry and lack of recognition, is axiomatic for the young writer coming to try his fortune in the great city.

We can instantly imagine the scene: the cobbled streets, the stinking rubbish, the tavern signs, the shuttered house-fronts; the moonlight and the dark alleys; the slumbering beggars, the footpads and the Night Watch; and the two central figures striding along, bent in conversation, convivial and ill-matched. Here is the huge, bony Johnson with his flapping horse-coat and dirty tie-wig, swinging the famous cudgel with which he once kept four muggers at bay until the Night Watch came up to rescue him; and here the small, elegant Savage with his black silk court-dress (remarked on at his trial), his moth-eaten cloak, his tasselled sword and his split shoes, which well-wishers were always trying to replace.

It is a night scene: these friends are outcasts from society, without money and without lodgings, talking of poetry and politics and reforming the world, while the wealthy complacent city slumbers in oblivion. They are in a sense its better conscience, ever wakeful; or its uneasy dream of oppression and injustice. It is a romantic, Quixotic, heroic or mock-heroic picture, depending on one’s point of view. But how true is it?

There are in fact four separate accounts of these night-wanderings. They are given by Sir John Hawkins, Johnson’s early biographer; by his young friend the Irish playwright, Arthur Murphy; by his later companion in the celebrated Club, the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds; and by Boswell. All depend on hearsay, for none of them actually knew Johnson at the time, or had ever seen him together with Savage. Indeed an extraordinary fact at once emerges: no one, at any time, or in any place, ever left a first-hand account of seeing Johnson and Savage together. It was, from the start, an invisible friendship.

The episode of their night-walks exists as a kind of composite memory rather than as a specific event which anyone witnessed. All the accounts must have had Johnson as their ultimate source, but the circumstances are never quite the same. To show how the story developed, it is interesting to unwrap each version and examine its layered contents. We begin with Boswell, and work backwards until we finally reach Johnson’s original account, dating from 1743.

Boswell was writing forty years later, and paints a general picture without describing a specific time or location in London. He emphasises the stoicism of the two friends whose imaginations could rise above the grim material facts of their poverty. ‘It is melancholy to reflect, that Johnson and Savage were sometimes in such extreme indigence, that they could not pay for a lodging; so that they have wandered together whole nights in the streets. Yet in these almost incredible scenes of distress, we may suppose that Savage mentioned many of the anecdotes with which Johnson afterwards enriched the Life of his unhappy companion, and those of other Poets.’2

Boswell seems to admit tacitly that there may be some picturesque exaggeration in Johnson’s fond recollections of these ‘almost incredible scenes of distress’. (Indeed the degree of Johnson’s poverty will bear further examination.) He likes to suppose that their talk was literary and anecdotal. He shrewdly imagines Johnson as collecting biographical ‘anecdotes’ from Savage, for the later Lives of the Poets; much as he in turn, many years later, would quiz Johnson for his own Life. His version of the night-walk is poetic: a handing-on of tales and traditions.

Uncharacteristically Boswell adds no visual details: nothing of dress, weather or season – a summer amble under the stars would presumably be very different from a winter tramp in rain or frost. But he does suggest, rather uneasily, that the two friends might sometimes have had enough money for other pursuits of the night, specifically drinking and whoring. ‘I am afraid, however, that by associating with Savage, who was habituated to the dissipation and licentiousness of the town, Johnson, though his good principles remained steady, did not entirely preserve [his] conduct … but was imperceptibly led into some indulgencies which occasioned much distress to his virtuous mind.’3

This is merely a hint, but a hint from Boswell on such a subject—experto crede—is much; and deserves to be borne in mind. So too does the rich London low-life material which Johnson subsequently incorporated into his Rambler essays, including a two-part biography of a country girl who becomes a prostitute, ‘The Story of Misella’. She ends her life in an appalling series of late-night taverns and infested night-cellars, which Johnson describes with bitter conviction:

Thus driven again into the Streets, I lived upon the least that could support me, and at Night accommodated myself under Penthouses as well as I could … In this abject state I have now passed four Years, the drudge of Extortion and the sport of Drunkenness; sometimes the Property of one man, and sometimes the common Prey of accidental Lewdness; at one time tricked up for sale by the Mistress of a Brothel, at another begging in the Streets to be relieved of Hunger by wickedness; without any hope in the Day but of finding some whom Folly or Excess may expose to my Allurements, and without any reflections at Night but such as Guilt and Terror impress upon me.

If those who pass their days in Plenty and Security could visit for an Hour the dismal Receptacles to which the Prostitute retires from her nocturnal Excursions, and see the Wretches that lie crowded together, mad with Intemperance, ghastly with Famine, nauseous with Filth, and noisome with Disease; it would not be easy for any degree of Abhorrence to harden them against Compassion, or to repress the Desire which they must immediately feel to rescue such numbers of Human Beings from a state so dreadful.4

Sir Joshua Reynolds’s account has a very different atmosphere. President of the Royal Academy, an elegant, easygoing man of the world, Reynolds had been fascinated with Savage’s story ever since he had first read Johnson’s Life in the 1750s. He had then shared with Johnson an acute dislike of aristocratic pretensions, and at a supper party in the presence of the Duchess of Argyll, the two pretended to be manual labourers, and loudly discussed the hourly wage-rate: ‘How much do you think you and I could get in a week, if we were to work as hard as we could?’5

Reynolds had first read of Savage on returning from his painter’s apprenticeship in Rome, casually picking up the book in a drawing-room in Devonshire. He began to read it ‘while he was standing with his arm leaning against a chimney-piece. It seized his attention so strongly, that, not being able to lay down the book till he had finished it, when he attempted to move, he found his arm totally benumbed.’6

This is a painter’s anecdote, mental attention represented by physical posture, with a certain flattering exaggeration of pose. Reynolds evidently questioned Johnson subsequently about his night-walks with Savage, and produced a witty bravura version, which would have told well in the Club. He supplies an exact location, a brisk amusing style, a conversational theme and a dramatic flourish at the end. All is high style and insouciance, a brilliant Society sketch:

[Johnson] told Sir Joshua Reynolds, that one night in particular, when Savage and he walked round St James’s Square for want of a lodging, they were not at all depressed by their situation; but in high spirits and brimful of patriotism, traversed the square for several hours, inveighed against the minister, and ‘resolved they would stand by their country.’7

The touch of heroic absurdity – two down-and-outs resolving to save the nation – is designed for indulgent laughter. But Reynolds, if he reports Johnson accurately, tells us two surprising things. The first is that the night-walks did not take place in the fabled zone of Grub Street but in the new, fashionable squares of the West End. The second is that their talk was not literary but political. They talked daring opposition politics against the corruption of the Whigs and the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole; and they praised ‘patriotism’, a specifically eighteenth-century usage, implying a radical politics which reviled the ‘German’ monarchy of the Hanoverians. Both this geography and this ideology throw a significant light on the young Johnson and his friend.

The compact geography of eighteenth-century London meant that the city could be crossed on foot in two hours, from the Tower in the south-east to Tyburn in the north-west. It represented a well-defined grid-map of power, professions and social classes. The central axis, running east-west parallel to the River Thames, was the broad boulevard of the Strand. Originally, as the name implies, the Strand was a riverside thoroughfare open to the water, with warehouses, shops, town houses, quaysides, and open unwalled shingle along its length. There was no regular Embankment, and no bridge across the river at this point. A painting by Canaletto, made from the terrace of Somerset House looking east in the 1740s, shows a broken vista of houses, balustrades and riverside steps going beyond St Paul’s to the single London Bridge at Southwark in the East End.

The river was itself a thoroughfare as busy as the Strand, packed with skiffs, wherries, sailing barges and every conceivable kind and size of water-taxi, which passengers hailed at scores of stairs, landing-stages and pontoons. This constant flow of human traffic, east-west along the Strand and the Thames, by day and night, represented the shuttle of power and business activity within the capital.

So, to the east of the Strand, from Ludgate to the Tower and Spitalfields, lay commercial London: banking, broking, shipping, publishing, manufacturing, and the slums. This was the original, historical sire of Grub Street, a narrow road of printers, taverns and lodging-houses roughly where the Barbican and the Museum of the City of London now stands.8 It was where Edward Cave had established his Gentleman’s Magazine, in rooms actually above the old medieval arch of St John’s Gate, in Clerkenwell, which young Johnson ‘beheld with reverence’ when he first arrived in London. It was where a young writer began when he came to seek his fortune, and where an old one ended if he had failed to find it. It was the kingdom of Alexander Pope’s Dunces. It was the East End of hope, and of despair.

But this is not where Johnson and Savage walked all night: they had gone ‘up West’ to the London of political power, wealth and social privilege. They were walking in enemy territory, the land to be conquered, and they came like spies in the night, their very presence a provocation.

To the west of the Strand, then, lay the smart coffee-houses of Charing Cross, the ministries of Westminster and Whitehall, Parliament and the Court, the royal parks and the elegant new squares of what became Mayfair. St James’s Square, only laid out in the 1720s, was the home of dukes and dandies, next to the clubs of St James’s and the royal palace itself. To talk of ministerial corruption and ‘patriotism’ here was like blowing a trumpet under the walls of Jericho. It was an heroic gesture, a defiant pose, which a painter like Reynolds would not forget.

Moreover, such a night-incursion into the domain of wealth and privilege was not a casual expedition. Reynolds may not have known this, but for Savage it was almost a ritual, repeated many times previously and solemnly enshrined in his own writings. In taking his young protégé Johnson into these familiar haunts, he was guiding him ceremonially, as Virgil guides Dante, through a purgatorial topography where much is to be learned by the angry young provincial, familiar only with book-learning:

The Moon, descending, saw us now pursue

The various Talk: – the City near in view!

Here from still Life (he cries) avert thy Sight,

And mark what Deeds adorn, or shame the Night!9

This is from the key poetic document of Savage’s career, the long visionary poem The Wanderer (1729), part meditation and part confession. Here, in its third canto, Savage describes such a night-pilgrimage through London. The young poet is guided by the Virgilian figure of ‘the Hermit’, a sage who has retired from the fret and folly of city life, to read poetry and philosophy in a cave and contemplate the wild beauty of Nature. This is one of Savage’s recurring fantasies of himself, as Johnson eventually came to understand.

The Hermit points out the glittering, delusive dissipations of the West End, as Savage must have instructed Johnson during their own nocturnal pacings round the squares of Mayfair:

Yon Mansion, made by beaming Tapers gay,

Drowns the dim Night, and counterfeits the Day.

From lumin’d windows glancing on the Eye,

Around, athwart, the frisking Shadows fly.

There Midnight Riot spreads illusive Joys,

And Fortune, Health, and dearer Time destroys.10

Against this glimpse of shadow play of aristocratic revelry the Hermit points out the solitary light from a garret window, which signals the ‘patriot’ poet hard at work, perhaps at the other end of the Strand, somewhere near Grub Street. For him, true wealth is not a handsome building, a property speculation, but an intellectual construction, a mental tower of learning and independent intelligence:

A feeble Taper, from yon lonesome Room,

Scatt’ring thin rays, just glimmers through the Gloom.

There sits the sapient BARD in museful Mood,

And glows impassion’d for his Country’s Good!

All the bright Spirits of the Just, combin’d,

Inform, refine, and prompt his tow’ring Mind!11

One may suspect, like Boswell, that Savage’s poetry was more improving than his conduct on such occasions. His Hermit, to say the least, is an idealisation. For it was on just such a night-walk, ten years before, that Savage had been involved in a brawl in a whorehouse, and killed a man and injured a woman, five minutes from St James’s Square in Charing Cross. As Johnson later observed, ‘The reigning Error of his Life was, that he mistook the Love for the Practice of Virtue’.12

When Johnson himself came to describe such night-walks in his own poem London (May 1738), he was much less dreamy and elevated. Indeed he was bitingly realistic, and we see again the big man with the cudgel. He seems to make some unmistakable reference to Savage’s less poetical exploits:

Prepare for Death, if here at Night you roam,

And sign your Will before you sup from Home.

Some fiery Fop, with new Commission vain,

Who sleeps on Brambles till he kills his Man;

Some frolick Drunkard, reeling from a Feast,

Provokes a Broil, and stabs you for a Jest.13

The irony here may be deeper than it first appears. Because this may be Savage himself speaking. There is considerable evidence that this passage, and indeed much of the poem, is a dramatic monologue written partly in Savage’s own voice. The whole of London may be partly Johnson’s attempt to render, in verse, the impact of Savage’s long conversations through the night. In this sense the poem could be considered as Johnson’s first version of Savage’s biography.

Certainly it seems true that Johnson first discovered in their night-walks the new form of intimate life-writing. It was to be like an extended conversation in the dark, taking ordinary facts and anecdotes, and pursuing them towards the shadowy and mysterious regions of a life, at the edge of the unknown or unknowable.

Johnson’s early impressions of these night-walks continue to be modified, in a complex way, by the other friends who recollected them. Arthur Murphy, a genial Irish playwright nearly twenty years Johnson’s junior, turned them into a piece of delightful comedy. Moving them even deeper into the West End, to the edge of Hyde Park, he added picturesque details of time and money, and with his playful turns of phrase seems to conjure up the witty outlines of a sketch that might have been written long after by Peacock or G. B. Shaw. (It should be read, perhaps, in a light Dublin brogue.)

Johnson has been often heard to relate, that he and Savage walked round Grosvenor Square till four in the morning; in the course of their conversation reforming the world, dethroning princes, establishing new forms of government, and giving laws to the several states of Europe, till, fatigued at length with their legislative office, they began to feel the want of refreshment; but could not muster up more than fourpence halfpenny.14

The ‘fourpence halfpenny’ is, of course, a spurious comic exactitude. Yet there is something about Murphy’s whole scenario, with its gracious absurdities, that carries a curious literary conviction. Why is this?

It is, surely, that Murphy has captured or suggested a premonition of the high, elegant, philosophic comedy of Johnson’s Rasselas (1759). The destitute Savage talking to Johnson about giving laws to Europe is not unlike the deluded Astronomer telling Prince Imlac that he has been secretly assigned the universal regulation of the weather. ‘… The sun has listened to my dictates, and passed from tropic to tropic by my direction; the clouds, at my call, have poured their waters, and the Nile has overflowed at my command; I have restrained the rage of the Dog Star, and mitigated the fervours of the Crab. The winds alone, of all the elemental powers, have hitherto refused my authority …’15

These confidences, too, are delivered in the dark, in the Astronomer’s turret, during a midnight storm. It was perhaps Savage who first gave Johnson the theme for Rasselas: that ‘dangerous prevalence of the imagination’ which Imlac discovers in the most interesting of human minds. Among those is the Poet himself, who must be acquainted with ‘all the modes of life’, who must commit his claims ‘to the justice of posterity’ and who must write ‘as the interpreter of nature, and the legislator of mankind’.16

Of all the versions of the night-walks which we have, it is that by Sir John Hawkins, with his direct knowledge of young Johnson from the mid-1740s, which most sharply emphasises the subversive political nature of their talks. Boswell consistently derides Hawkins’s accounts, not merely because he is the chief rival biographer, an amateur and musicologist, and so gratifyingly full of factual errors and ‘solemn inexactitudes’. For Hawkins, himself a lonely and awkward personality, gives an altogether rougher, darker, more emotionally unstable picture of the young writer finding his path than Boswell’s hero-worship will allow.

Hawkins’s youthful Johnson is never a comfortable figure, never a natural Tory clubman. He is anxious, self-doubting and obsessive. His politics, like his whole personality, are fierce and to some degree disruptive. Boswell could never be easy with this. Hawkins sees immediate common political ground between the two outcasts. ‘They had both felt the pangs of poverty, and the want of patronage: Savage had let loose his resentment against the possessors of wealth, in a collection of poems printed about the year 1727, and Johnson was ripe for an avowal of the same sentiments.’17

They both shared, according to Hawkins, ‘the vulgar opinion, that the world is divided into two classes, of men of merit without riches, and men of wealth without merit’. Hawkins also says that Savage’s ‘principles of patriotism’ – the semi-subversive Opposition to the Whig Government and the Hanoverian Crown – shaped Johnson’s political outlook during their talks, and may even have made him run the risk of Jacobite treason. ‘They both saw with the same eye, or believed they saw, that the then Minister meditated the ruin of this country; that Excise Laws, standing Armies, and penal Statutes, were the mean by which he [Walpole] meant to effect it; and, at the risk of their liberty, they were bent to oppose his measures …’18

Hawkins’s evident disapproval of this youthful radicalism makes it all the more convincing as evidence. It is exactly these political themes that Johnson does go on to address in his earliest, anonymous poetry and prose, up to the age of thirty-five. In the satire London, it takes the form of a general charge of political corruption against those in power:

Here let those reign, whom Pensions can incite

To vote a Patriot black, a Courtier white;

Explain their Country’s dear-bought Rights away,

And plead for Pirates in the Face of Day …19

In the pamphlet Marmor Norfolciense (1739) – viz. ‘The Stone of Norfolk’ – it becomes a specific attack on the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole (whose estates lay in that county), and Hanoverian rule. As a recent critic, Thomas Kaminski, has observed, here ‘we find a Johnson unknown to the readers of Boswell – a rabid, harsh opponent of the ruling government, a critic not only of a party but of the King’.20 And in the Latin pastiche ‘prophesy’, attached to the pamphlet, which Johnson translated as the poem ‘To Posterity’, we meet a baleful vision of complete national subversion, the land overrun by alien redcoat soldiers, and the entire British population ready for rebellion:

Whene’er this Stone, now hid beneath the Lake,

The Horse shall trample, or the Plough shall break,

Then, O my Country! shalt thou groan distrest,

Grief swell thine Eyes, and Terror chill thy Breast.

Thy Streets with Violence of Woe shall sound,

Loud as the Billows bursting on the Ground.

Then thro’ thy Fields shall scarlet Reptiles stray,

And Rapine and Pollution mark their Way …

Then o’er the World shall Discord stretch her Wings,

Kings change their Laws, and Kingdoms change their Kings.21

So Hawkins’s night-walk is that of romantic, political malcontents. The two men are penurious, angry, to some degree sinister. The walk has a wintry atmosphere, chill and discomforting, with even a hint of cloak and dagger. Like Boswell, like Reynolds, like Murphy, Hawkins also says he is telling the story directly as Johnson described it; only as something that happened frequently, perhaps over many months.

Johnson has told me, that whole nights have been spent by him and Savage in conversations of this kind, not under the hospitable roof of a tavern, where warmth might have invigorated their spirits, and wine dispelled their care; but in a perambulation round the squares of Westminster, St James’s in particular, when all the money they could both raise was less than sufficient to purchase for them the shelter and sordid comforts of a night cellar. Of the result of their conversations little can now be known, save, that they gave rise to those principles of patriotism, that both, for some years after, avowed.22

Hawkins’s suspicions would have been further darkened had he known – or had he suspected that Johnson knew – that Savage, many years previously, had actually been arrested and questioned on a charge of treasonable, Jacobite publication; and that for some months he was the subject of Secret Service reports.23 Whether young Johnson knew this then, or later, will soon become a leading question about their friendship.

For Johnson himself these night-conversations in London with Savage were a transforming experience. They shaped his idea of the city itself, his politics, and his whole notion of the writer’s task and situation. That Savage appeared both poor and outcast must have struck him as bitterly ironic and yet curiously glamorous. Here was a brilliant, strange and enchanting man, who had known all the leading writers of the day – Sir Richard Steele, Colley Cibber, Alexander Pope, James Thomson – and moved in circles close to Parliament and the Court. Yet he was reduced to the back streets, he voiced subversive politics, and he befriended someone as obscure and socially inept (not to say monstrous) as Johnson himself.

Savage needed company and talk, needed them with something approaching desperation, to act out his own life and his extensive fantasies. This soon became clear to Johnson. In this too there was at once a common bond. Both men dreaded solitude, and Savage had found a remedy with which Johnson instantly identified. Talk held off the terrors and depressions of loneliness.

‘His Method of Life particularly qualified him for Conversation, of which he knew how to practise all the Graces,’ wrote Johnson appreciatively. ‘His Language was vivacious and elegant, and equally happy upon grave or humorous Subjects. He was generally censured for not knowing when to retire, but that was not the Defect of his Judgment, but of his Fortune; when he left his Company he was frequently to spend the remaining Part of the Night in the Street, or at least was abandoned to gloomy Reflections, which it is not strange that he delayed as long as he could …’24 This could be Johnson writing of himself. One can begin to see how sympathetically two such men might meet, as Cave’s offices emptied at Clerkenwell, or the taverns closed along the Strand.

So when Johnson came to write Savage’s Life in 1743, he put Savage’s night-walking at the heart of the story of his literary career. He did it so powerfully that he created a legend, almost an eighteenth-century archetype, of the Outcast Poet moving through an infernal cityscape, the ‘City of Dreadful Night’, in which his eye alone witnesses the horror, filth and misery that the rich and powerful have created as they slumber, uncaring.

To achieve this, Johnson does something extraordinary. He completely withdraws himself from the story. He never makes a single mention of himself as Savage’s night-time companion. The two Hogarthian figures, joined in their companionable talk, who appear again and again in the memoirs, never once appear in Johnson’s original account. Savage is essentially, and one might say symbolically, alone.

Johnson places this description or evocation of the Outcast Poet at a pivotal moment in his own narrative. It is set in 1737, immediately after the publication of Savage’s poem ‘Of Public Spirit’ (including an extract in the Gentleman’s Magazine), and at the time that Johnson himself first arrived in the city and became aware of Savage’s work (though this fact is studiously omitted).25

The theme of Savage’s poem is also dramatically relevant. It considers how far the State is responsible for the poor, incapacitated or underprivileged in society; and in particular whether the Whig policy of expatriation – forcible emigration to the new colonies in North America and Africa – can be morally justified. Is this ‘out-casting’ of men from their native homes and families, a true expression of ‘Public Spirit’?

Rising above his own situation, like the true poet, Savage touches on this general issue of social justice, which Johnson summarises with angry force:

The Politician, when he considers Men driven into other Countries for Shelter, and obliged to retire to Forests and Deserts, and pass their Lives and fix their Posterity in the remotest Corners of the World, to avoid those Hardships which they suffer or fear in their native Place, may very properly enquire why the Legislature does not provide a Remedy for these Miseries, rather than encourage an Escape from them. He may conclude, that the Flight of every honest Man is a Loss to the Community …26

But Savage, here presented by Johnson as the spokesman for the oppressed, goes much further than this. He attacks the whole notion of colonisation itself.

In historical terms of the early eighteenth century this is a truly radical position. Savage runs directly counter to the prevailing maritime, trading and enterprise culture of commercial exploitation, which Walpole’s administration notoriously represented, with support for such institutions as the South Sea Company and the East India Company. Again, Johnson’s summary is forceful and angry: ‘Savage has not forgotten … to censure those Crimes which have been generally committed by the Discoverers of new Regions, and to expose the enormous Wickedness of making War upon barbarous Nations because they cannot resist, and of invading Countries because they are fruitful; of extending Navigation only to propagate Vice, and of visiting distant Lands only to lay them waste.’27 Ever afterwards, this anti-Imperialist stance became Johnson’s own.

In his poem Savage is specific about colonial exploitation. To illustrate this, Johnson does something new in literary biography. He quotes extensively from the poetry and begins to integrate these quotations into the texture of his prose narrative by placing them in careful footnotes. These quotations are, technically, a new biographical device, because they bring us an impression of Savage’s own voice, of Savage actually talking to the reader (and of how he talked to Johnson). It is the biographer’s answer to the novelist’s most powerful mode of verisimilitude: direct speech.

The quotations perform the role of ‘authentic’ monologue, a mode which would normally imply that very fictionalisation which Johnson had dismissed as a legitimate means of historical truth. By taking them from Savage’s own poetry, Johnson gives them textual authenticity: these are his own words, they are not invented, but they strike us in his own voice, they are what he actually said. Moreover, by using extracts, Johnson effectively reanimates Savage’s work.

Savage’s lines paradoxically work much better as fragments of contemporary reported speech than as more formal and extended passages of mid-eighteenth-century poetry. That is, compared to the best of Pope or Thomson they are weak; but compared to some of the diffuse, first-person narratives of Defoe or Eliza Haywood they are vividly alive. As a critic, Johnson knew that ‘Of Public Spirit’ was a slapdash performance – ‘not sufficiently polished in the Language, or enlivened in the Imagery, or digested in the Plan’.28 But as a biographer he knew it was deeply expressive, and conveyed one aspect of Savage’s fantastic idealising power with great intensity.

Savage’s two main targets are the East India trade in silks, spices, hardwoods and other luxury goods; and the West African trade in black slaves. Both produce their own kinds of oppression, and make outcasts of men powerless within their system. In India he sees this primarily as a cultural oppression, in which the indigenous populations are simply subdued by the Western traders, who care nothing about native laws, customs or religions. He calls on the colonisers to be more respectful, more just, more generous:

Do you the neighb’ring, blameless Indian aid,

Culture what he neglects, not his invade;

Dare not, oh! dare not, with ambitious View,

Force or demand Subjection, never due.29

In Africa, he recognises with horror a trade in human bodies that is both indefensible in itself and cruel and hypocritical in its operation. The great Whig merchants, so much of whose personal wealth, houses, estates and even servants are drawn directly or indirectly from this trade, defend themselves with the cry that ‘while they enslave, they civilize’.30

The black servant – especially as coach-driver, table-waiter or personal valet – was a familiar feature of eighteenth-century London smart society. Johnson himself later took on a black manservant, Frank Barber, originally as a wild and illiterate teenager, who promptly ran away to sea. But this was one of Johnson’s spiritual reparations: he took infinite trouble to trace him, buy him out of the service, educate him, provide for him and his family, and eventually made him an inheritor in his will, so he became virtually an adopted son, ending his days in ease in Hampshire, corresponding genially with Boswell. Savage saw this enslavement with acute revulsion, which suggests at some level a personal identification:

Why must I Afric’s sable Children see

Vended for Slaves, though form’d by Nature free,

The nameless Tortures cruel Minds invent,

Those to subject, whom Nature equal meant?31

The clue to this identification may lie in the word ‘cruel’, which Johnson discovered had an almost talismanic significance for Savage’s personal mythology. But the political implications for Savage of such colonial and imperial attitudes were frankly apocalyptic. The imperial London through which they walked, like Cassandras in the night, might be destroyed by its own unjustly subject peoples. The wheel of fortune and of power would turn round; the outcasts would occupy the inner seats of power:

Revolving Empire you and yours may doom;

Rome all subdued, yet Vandals vanquish’d Rome:

Yes, Empire may revolve, give them the Day,

And Yoke may Yoke, and Blood may Blood repay.32

These parallels with the decline and fall of Rome were particularly significant to Johnson, because they were to lead him to the satires of the second-century Roman poet Juvenal, as a new model for his own poetic persona in London.

Savage and Juvenal were always closely connected in Johnson’s mind as critics of a corrupt, materialist, urban society. Savage roamed through London as Juvenal once roamed through Rome; and Johnson followed both.

With the publication of his poem ‘Of Public Spirit’ in June 1737, Johnson is able to present Savage as he first perceived him. He is the spokesman for the outcast, the oppressed, the ‘sons of Misery’.33 He is even the spokesman for the daughters of misery, the prostitutes of the city, the ‘beauteous Wretches’ who the ‘nightly Streets annoy, / Live but themselves and others to destroy’.34 Savage stands out against social injustice. ‘He has asserted the natural Equality of Mankind, and endeavoured to suppress that Pride which inclines Men to imagine that Right is the Consequence of Power.’35 He writes with ‘Tenderness’.36

It is against this heroic moral background that Johnson carefully places his portrait of the Outcast Poet. In biographical terms it is a close-up, or a montage of street scenes, animated and visualised. It is written with great force and anger, with almost poetic power.

The first paragraph enacts Savage’s progress through the dark labyrinth of streets in a single, unwinding sentence. Its keynote is one of pathos:

He lodged as much by Accident as he dined and passed the Night, sometimes in mean Houses, which are set open at Night to any casual Wanderers, sometimes in Cellars among the Riot and Filth of the meanest and most profligate of the Rabble; and sometimes, when he had no Money to support even the Expences of these Receptacles, walked about the Streets till he was weary, and lay down in the Summer upon a Bulk, or in the Winter with his Associates in Poverty, among the Ashes of a Glass-house.37

Clearly this is not the experience of one bohemian summer night out in the West End. This is a dreadful, Dantesque repetition, at all seasons, and at many locations over London: alleys behind the Strand, off Covent Garden, beyond the Fleet Ditch, behind St Paul’s, in Clerkenwell, off Smithfield, out in Spitalfields.

The alternative forms of lodging open to Savage mark the stages of a humiliating decline from poverty to absolute indigence. The ‘mean House’ would be a penny-a-night public lodging or spike, with stinking dormitories of wooden beds. The ‘Cellar’ would be a single, dark, basement dossing-room of sacks and straw heaps, fouled with urine and vomit, populated by drunks, diseased and ageing prostitutes, lunatics, tramps and psychopaths (the very same in which Johnson finds ‘Misella’).

The ‘Bulk’ was a low, wooden stall attached to a shop-front on which fresh market produce was displayed by day and left to rot at night: old vegetables at Covent Garden, old fish at Billingsgate, old meat at Smithfield. The ‘Glass-house’ was a small factory (like a bakery or kiln) where carriage-glass, window-panes, water jugs, wine-glasses, decorative buttons, cane-tops and other fancy ornaments were melted and cast in fast-burning coal-fired ovens, found all over the East End, with their brick chimneys billowing smoke and their backyards full of warm grey ash and clinker.

Here even a complete down-and-out could keep warm (just as the modern tramp sleeps on a ventilation-grille), though rising as ash-grey as a ghost in the morning. Thus Johnson charts Savage’s decline in the infernal city night; falling as low, if not lower, than those whose rights he ‘asserted’ as a poet.

The ashes of the Glass-house (like the ashes of the grave) may have had a particularly emotive overtone for the eighteenth-century reader. Glassware of all kinds, as opposed to metal or wood, was the province of the rich, and the expression of luxury and refinement. Even the clinker, which smelted into fantastic shapes and vivid oxidised colours, might be prized. It is an expressive irony that Savage’s one-time editor and publisher, the wealthy Aaron Hill, once planned to construct a 300-foot-square rockery in his splendid Richmond garden, composed of blue stones, seashells bought from London toyshops and ‘chosen clinkers, from the glass-houses’. The clinkers were to be carefully ‘picked out of the cinder heaps, and brought in boats’ up the Thames from the East End. On the top of this rockery Hill planned to build an elaborate Chinese summerhouse as an allegorical ‘Temple of Happiness’.38

Johnson never identifies himself as an ‘associate in Poverty’ with Savage, among those ashes. Yet he writes with an immediacy that suggests familiarity – if not first-hand knowledge – of such ‘Receptacles’ of the London night. He is rhetorically present, giving plain and moving testimony.

In the second paragraph Johnson stands back. Pathos turns to anger, plain testimony to high irony. This contrapuntal shift of keys or tones becomes one of Johnson’s most subtle methods of interpreting Savage’s life through narrative. He repeats the stations of Savage’s humiliation, word for word, object for object. But now he sets them into literary perspective with a note of bitter elegy. His phrases are shaped, given a rhythm and mounting climax of outrage. The Tramp is revealed as the Poet, and the ‘casual Wanderer’ becomes again the author of his greatest poem. Johnson for the first time reveals how passionately he feels about his friend, and how profoundly he identifies with Savage’s outcast situation.

In this Manner were passed those Days and those Nights, which Nature had enabled him to have employed in elevated Speculations, useful Studies, or pleasing Conversation. On a Bulk, in a Cellar, or in a Glass-house among Thieves and Beggars, was to be found the Author of the Wanderer, the Man of exalted Sentiments, extensive Views and curious Observations, the Man whose Remarks on Life might have assisted the Statesman, whose Ideas of Virtue might have enlightened the Moralist, whose Eloquence might have influenced Senates, and whose Delicacy might have polished Courts.39

The noble cadences into which Johnson finally lifts this passage, suggest that for his young listener Savage’s night-talk in the London streets sometimes approached the condition of poetry. It is a public poetry, which should have concerned the ‘Moralist’, the ‘Statesman’, the men in power at Parliament (‘Senates’) and at Court. In this sense Savage fulfilled the Augustan concept of the poet as potential ‘legislator’, put forward in Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia and reiterated by Imlac in Rasselas. But because of Savage’s outcast state, his poverty and humiliating sufferings, it is poetry which is not heard, not acknowledged, by those in power ‘Of Public Spirit’ sells exactly seventy-two copies.40 Savage is, for young Johnson, the poet who has no place, no social position, no influence on affairs, and literally no home.

Johnson is in effect making a Romantic claim for him. Savage is the Poet as Outcast, the poet as ‘unacknowledged legislator’. This was to be exactly the claim that, fifty years later, the anarchist philosopher William Godwin would make for all poets in Political Justice (1792); and his son-in-law Shelley would make with openly revolutionary intent in A Philosophical View of Reform (1820) and A Defence of Poetry (1821). Johnson had identified in Savage a new poetical archetype. He had, astonishingly, glimpsed in the back streets the first stirrings of the new Romantic age.

One further incident becomes part of Johnson’s heroic account of Savage’s night-existence in the great city. Johnson wrote: ‘Savage was … so touched with the Discovery of his real Mother, that it was his frequent Practice to walk in the dark Evenings for several Hours before her Door, in Hopes of seeing her as she might come by Accident to the Window, or cross her Apartment with a Candle in her Hand.’41

This haunting image of the figure shut out from the lit window, of the man in the edge of shadows and the beloved woman with her candle, also becomes an archetype of the Romantic outsider and can be traced down through popular fiction, even to its Victorian apotheosis in the figure of Heathcliff outside Cathy’s window in Wuthering Heights.

However, there may be another interpretation of this incident. Savage may not be a figure of pathos but of terror; not patiently waiting, but violently seeking entry; not a poetic outcast, but a pathological intruder.