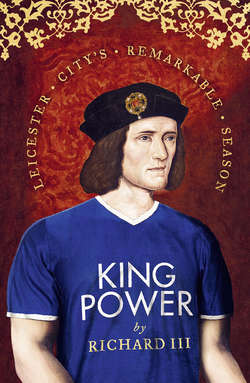

Читать книгу King Power: Leicester City’s Remarkable Season - Richard III, King of England Richard III - Страница 7

THE CAR PARK

ОглавлениеI, Richard Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester, Lord Protector, loyal brother (ahem) to one king, loving uncle to another mysteriously vanish’d (though I never knew a thing of that, not a dickie bird), called Dickon by some, Crookback by more, King Richard of England for too short time, later of the City Council Car Park, New Street, Leicester LE1 5PS (special rates weekends and bank holidays), latterly reinterred in seemly place … I, Richard III, am now about to write the curious story of my afterlife.

Yet that misleads where no deception’s meant. ’Tis not merely, nor even mostly, of my own afterlife I shall write. For that may all too swiftly be thus condensed:

Afterlife of Richard III

Died 22 August 1485

Laid to rest in a car park

Remains discovered September 2012

Exhumed

DNA tested (an acid, so I’m told, that weaves and meanders through the blood, and is the very building block of life)

Confirmed as Richard Plantagenet

Reburied Leicester Cathedral, March 2015

No, reader, the afterlife concerning us here is that of my most wellbeloved association football club: Leicester Fosse as was, Leicester City as is, Foxes to friend and foe alike, whose King Power arena stands but a mile from the church wherein I now lie. Those Foxes who, little more than one brief year ago, lay ensnared in relegation’s trap, encircled by ravening hounds, their route to safety obscure unto the eye.

Yet from those depths we did rally and revive. Premier litter runts one spring reborn, we were rulers of the league the next. Aye, ’tis Leicester’s salvation from a shameful grave, and not so much my own, of which I write. And if I played a ghostly part in that, ’tis not for me to speak of preternatural things.

The question must nonetheless be asked, for who would leave this tale unexplor’d? How was last winter of our discontent made glorious by that son of Yorkshire, the Sheffield-born Jamie Vardy, and the steely bunch of misfits at his side?

This question is asked in realms across the globe. Discredited they were as fools and knaves. Marooned at foot of table, distended from the rest by many points, magnet for contempt across this land, as once I was, inexorably we were headed for the drop.

Yet now of those brave warriors – of Vardy who once did make prosthetic limb, and of Mahrez, the Moor from Maghreb come; of Kasper Schmeichel, the Viking between the posts, of Huth, forsooth, and of others too – the world entire speaks in reverent tones.

I have hinted meekly at the truth, for fear of charging centre stage when I be better hidden in the wings. But let me put the question now in clear and ringing terms, for dissembling is a fault in English kings.

Was the confluence of my reburial and Leicester’s revival naught but chance? Or by lying close to the Foxes’ ground, supine though I am and wrapped in shroud, was I a Moses to part the foamy tide, and lead my boys towards the promised land?

Coincidence? Or king power?

Decide this for thyselves. I say nothing either way.

For ’tis ne’er the way of kings to boast and brag,

Our princely state speaks well enough for us.

Lesser men yell self-aggrandising fuss,

In crown alone a king hath ample swag.

To you it falls, descendants of my subjects, to judge whether the Prince who fell at Bosworth Field, the last of England’s kings to die in war – you think you’d have caught one of those powdered Hanoverian ponces wielding a sword? Or that lascivious buffoon Charles II, who slavered over that buxom bint with the oranges? – is Leicester City’s salvation. All I will do is state these barren facts. Perchance they tell a tale upon their own.

’Twas on 5 September 2012 that men and women with spades – ‘archaeologists’, in the modern parlance – located the Church of Grey Friars in Leicester town, where a monument to me was known once to have stood, beneath ranks of metal motor horses serried in their oblong bays above.

I would not dwell upon the dusty past, for memory gives cause for melancholy yet. But it was there within that church, after I breathed my last one August day of 1485, that I was hastily laid to rest, without the ritual or the honour due my rank. And there it was that my waxen flesh decayed, until spine-curved skeleton was all that did remain.

If ever you saw the stage amusement bearing my name, as writ by that girlish, meretricious bard, you’ll know me for a wretch with hunch for back. A pitiful freak to all with eyes, like that Frankish git who roamed another cathedral by the Seine, forever plapping forth about his bells.

True it is that when I was a child, and ventured forth beyond Fotheringay Castle walls to take the airs, the boys who could not play for want of ball would point towards my back, accusing me of theft until I, enraged, replied: ‘How many times? I haven’t got your fucking ball.’

If neither the curving of spine nor yet the withering of limbs were so great as some have made them look – you can’t legislate against Tudor propaganda – a pretty sight I never was, for sure.

It was not in sooth entirely a hunch, but a malaise that came upon me as a child to twist me out of form. Idiopathic scoliosis is the doctorly term today. Google it at leisure for thyselves.

I do not beg thy pity for my shape, invert’d cur and hideous though I was. But kicking an inflated pig’s bladder, with fellows of my age – if not my rank – was a childhood joy denied me by this fate.

Like Clau-Clau-Claudius of Rome, lame stammerer who for a halfwit was mistook, I was not by nature shaped for sportive tricks. Deform’d, unfinish’d, sent forth before my time, I could not run or frolic with my contemporaries. But love the game I did from infant days, when nurse would make me stand between the posts, kicking inflated pig’s bladder towards her target while I, tiny custodian, did dive across the goal.

I was no Gordon Banks, who dived to save from Pelé like a salmon.

For I was small and bent, and for a ball had only blown-up gammon.

And again like Claudius, who long before me grew to rule where none foresaw, you could have got longer than 5,000–1, from the turf-accountant firm of WagerFred, against me taking the title coveted by all. The odds when I was born, the twelfth of thirteen babes to slither from one mother’s womb, in the autumntide of 1452, were in the many millions sure enough.

Yet that longed-for title I eventually did seize. My path to throne was winding as my spine, and how I journeyed isn’t swiftly told. Do Google, once again, if fancy takes. But don’t believe each and every word you read. Those were dangerous, violent times, and demanded stringent measures. We could not afford to be angels in those days.

Anyway, suffice it that I became the king in summertime of 1483, when I not long since had thirty turned, after my brother Edward IV left this earth. Tragically uncrowned was his son Edward V. Lovely kid, and so was his brother, Richard of Shrewsbury. Straight up – and yes, thanking you, I get the irony of that, stooping crookback that I was – you couldn’t put a price upon my grief when my nephews vanished from the Tower, though how or where they went none truly knows.

So it was in their absence that, come July that year when they were handing out the sceptres, it was I who received the premier title of England, the last of the House of York anointed in sight of God.

Funny old game, monarchy. All men crave it, and most would yield their lives merely to play the game of thrones at all. Yet uneasy hangs the head that wears the crown, for menace of dethronement cleaves ever close.

Know who’d confirm that? Nigel Pearson, twice our gaffer at Leicester City, that’s who. Nigel’s first spell as ruler endured but two years, like my own. Then he fell, though at the hand of our club chairman, the Slavic invader Milan Mandarić, not one of warlord Henry Tudor’s strikers with an axe.

Yet now and again a king doth rise again. Our Lord Jesus did so, gospel states, and so did my brother Edward IV, who was ousted by the Lancastrian Henry VI only to slaughter Henry (with a little help from his friends and relatives, truth be told) and be restored as king.

Like my brother, Nigel Pearson soon enough regained his throne. In 2010, ownership of Leicester City passed to Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha, the leader of a company of men from the distant eastern land of Old Siam, who call themselves King Power Duty Free. Though by the thrice-beshitten shroud of Satan, what witless gibberish is that? For tell me how the power of a king can from onerous chains of duty e’er be loosed?

And it’s Leicester City, Leicester City FC.

We’re by far the greatest team

The world has ever seen.

Who now would gainsay the wisdom of such words? Yet in autumn of 2011, it struck the ear as a sardonic chant. For my Foxes languished low in the second tier, the so-called ‘Championship’ (I can’t be doing with these rebrandings. Second Division’s still good enough for me), when Srivaddhanaprabha restored Nigel to his coachly post.

Time and space are short, so we must leap ahead in mighty bounds. One year after Pearson’s restoration, I was discovered in car park tomb. Eighteen months after that, in May 2014, we rose again to the highest league, whither and thither we have yo-yo’d for so long.

The Premier League season did commence in August of that year, and hand on heart, our fortunes prospered not. A burst of joy when we thumped Man United 5–3 at home soon enough gave way to direst gloom. Christmas found us propping up the league, far adrift from every other club. In all the years that passed, but twice had Yuletide stragglers escaped the drop.

The New Year brought no succour, and in February all seemed lost. So did Nigel Pearson for a time. At home to Crystal Palace, trailing and fated to lose by one to nil, this bullish man did squeeze a rival player’s neck. It later spread abroad that he was gone, discharged. He thought himself that P45 was his. Yet a change of heart was had, and Pearson stayed, and gaffer still was he next month when the car park I forsook.

On 22 March of the year 2015, my skeleton was carried in procession to Leicester Cathedral, where four days later I duly was interred. The Archbishop of Canterbury attended, and members of the ruling house. Insultingly minor members, I might add. My namesake Duke of Gloucester (gormless old buffer) and Prince Edward’s missus, the Countess of Wessex. Would it have killed them to send a big gun like Philip, Prince of Denmark as well as Greece? Or Charles, who doth converse with flora to fill the time while waiting upon his queenly mother’s death?

But what doth it profit us to carp? Besides, the day was not a dead loss. That prancing mime Benedict Cumberbatch did read aloud an ode, as writ by Carol Ann Duffy, the Laureate of the land. I reproduce it, without anyone’s kind permission but by the right of kings, below.

Richard

My bones, scripted in light, upon cold soil,

a human braille. My skull, scarred by a crown,

emptied of history. Describe my soul

as incense, votive, vanishing; your own

the same. Grant me the carving of my name.

These relics, bless. Imagine you re-tie

a broken string and on it thread a cross,

the symbol severed from me when I died.

The end of time – an unknown, unfelt loss –

unless the Resurrection of the Dead …

or I once dreamed of this, your future breath

in prayer for me, lost long, forever found;

or sensed you from the backstage of my death,

as kings glimpse shadows on a battleground.

Well, I’m sure it made sense at the time.

Anyway, speaking of the Resurrection of the Dead, five days before my sepulchral rites were read, the Foxes travelled south to take on Spurs. You recall Harry Hotspur from Henry IV, Part I? In that other of Shakespeare’s abominations, he was slain in single combat by the son of the Lancastrian usurper whose name the play doth bear.

The Tottenham team that bears his own ignoble name did unto us what Prince Hal did to him.

Down we went by three goals to their four. Beneath us opened wider the Premier League trapdoor, as the ensuing chart confirms:

Bottom of the Premier League table on 26 March 2015, the day of Richard III’s reburial in Leicester Cathedral

Pretty perusal it hardly makes, for all that game in hand. The portents worse could not have been. No team had e’er escaped so late from so cavernous a pit, distended seven points from survival’s berth (seventeenth place, for the hard of comprehending) with but nine games to play.

The first encounter after my burial was done brought West Ham’s blue and claret to our ground. With bare four minutes left upon the clock, the match tied up at just one goal apiece, it fell to a King – as so perforce it should – to loose the bonds of doom that crushed our bones.

The wily Pearson had sent on Andy King, a Foxes valiant of many years, in place of one who left for dugout’s rest. And King it was who won the match for us, scrambling home when Vardy mishit in haste.

Once lit, the torch of revival grew quick to blaze. West across the Midlands we fared next, to the Hawthorns, there to meet West Brom. A deficit of 1–2 when just ten minutes did remain was flipped upon its head in thrilling style. ’Twas Robert Huth, our lion of Biesdorf, who levelled by heading home from close. And then came drama wholly unconstrained, in time added by the ref for wounds and woes, when Vardy, racing clear from bare halfway, did shoot the ball an inch inside a post. Three–two to the Foxes.

‘We can’t get carried away,’ the gallant Pearson told the press,

Adding meekly, ‘We still have much to do.’

But escape by now had hoven into view,

And on and on it went, this strange success.

Seven days later, goals unanswered from Ulloa and King again did for Swansea City. Another week. Then to hateful Lancashire we went, where on the hour a Vardy party came when Jamie the winner scored at Burnley’s home.

Reminding us the sailing’s seldom smooth, we then did lose at home by three to one to Chelsea, poised to win the Premier League under aegis of a Portugueser of whom more anon.

But then, God be praised, the miracle resumed. Newcastle first and then the south coast Saints were vanquished without concession of a goal. And though at Sunderland no goals were scored by either side, the season’s finale was a veritable Foxes landslide, a 5–1 thumping of poorly Queen’s Park Rangers, who took the twentieth spot that once seemed the destiny of us alone.

I won’t bang on again about what part I played – if any part at all, however slight – in raising the living dead to vibrant life. Nor will I remind you that those Foxes, doomed for sure when came the Ides of March, won seven of their final nine after I was reinterr’d, and finished in respectable fourteenth place.

The seeds of legend soon to come to bloom were in those few short weeks sown in fallow ground. And to our heroes each we’ll come anon.

But what of Nigel Pearson, doughty helmsman who steered us free from rocks? What lustrous reward lay in store for him? Aye, there’s the rub.

Uneasy, as I mentioned, hangs the crown,

And unpunish’d no good deed doth ever go.

For all that, here’s what I would wish to know:

What would have befallen Nige if we’d gone down?