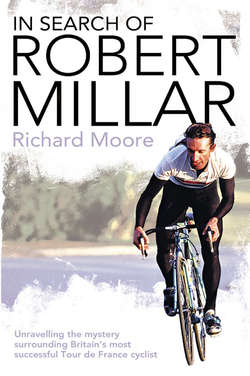

Читать книгу In Search of Robert Millar: Unravelling the Mystery Surrounding Britain’s Most Successful Tour de France Cyclist - Richard Moore - Страница 7

Prologue

ОглавлениеI can remember, quite clearly, my first encounter with Robert Millar. It was at lunchtime on Saturday, 21 July 1984. I was 11 at the time. Robert Millar will remember the occasion more vividly, because while I was watching television with my dad in my family’s living room, he was in the Haute-Ariège area of the Pyrenees, climbing a steep, winding road that ended at the ski station at Guzet Neige – the finish of stage 11 of the Tour de France.

We had recently moved to England from Scotland, and my Scottishness was being pointed out to me repeatedly. A PE teacher nicknamed me ‘Jock’, and it stuck. I hated being singled out. On the other hand, I quite liked it too. But I was desperately, urgently looking for allies – namely, fellow Jocks – wherever I could, even on television, even participating in obscure sporting events. I looked at the TV screen but couldn’t really work out what was going on. There was a small group of sweating cyclists straining against a steep gradient and suffering in the blazing heat. So this was the Tour de France. It looked pretty boring.

I asked my dad, who was receiving his weekly fix of the Tour de France on ITV’s World of Sport, whether any Scottish cyclists were competing in this strange event. ‘There is one Scot,’ he replied, a note of surprise in his voice. ‘Robert Millar, from Glasgow. That’s him there.’

Now I was interested. I was struck by the name, by its ordinariness. He didn’t sound like he belonged there. ‘Robert Millar’ jarred alongside the exotic-sounding Laurent Fignon, Bernard Hinault, Pedro Delgado, even the American with the French-sounding name, Greg LeMond. And yet, although I didn’t know it at the time, in the wiry, compact form of Robert Millar I had just stumbled upon someone who was not only Scottish but most certainly – and defiantly – different; someone who didn’t just mind standing out, or apart, from the crowd, but actually seemed to want to.

‘Will he win?’ I asked.

‘No,’ said my dad, with good old-fashioned Scottish pessimism-realism.

But Dad was wrong, or at least partially wrong. I kept watching. I can vividly recall the footage of the Tour on that particular day, with commentary that sounded like it was coming from outer space. The grainy quality of the pictures and the sounds made the broadcast seem other-worldly. It was, in fact, less like watching sport and more like witnessing astronauts landing on the moon, or mountaineers arriving at the summit of Everest. And I remember Millar winning the stage, his second Pyrenean victory in consecutive years, on his way to claiming one of the race’s three great prizes, the title of King of the Mountains. He was the first and to this day remains the only English speaker ever to wear the fabled polka-dot jersey awarded to the King of the Mountains all the way to the finish in Paris.

There was something about Millar, quite apart from his nationality and the fact that he was beating these foreigners at their own game, on their own turf, to the top of their own mountains, that was instantly fascinating. As he climbed the mountain his head bobbed gently and easily to the rhythm of the pedals. His style was unusual but fluid and efficient. His left knee flicked in and then out at the top of the pedal stroke, following a consistent, smooth pattern. His eyes were focused a few yards in front, yet they also appeared vacant, expressionless, drawn with the effort – ‘the face of a hungry man’, according to the commentator, Phil Liggett.

That Saturday afternoon Millar was in the company of three other cyclists, but when the slope reared up, he was the one doing most of the pace setting. He seemed to be teeming with nervous energy, repeatedly looking over his shoulder, checking the others, cajoling them even. While he was fleet of foot, they were leaden by comparison; the slender, lightweight Scot looked as if he might fly off at any moment, the others as if they would be dragged back down the hill by the pull of gravity. ‘I hope he doesn’t overdo it with his confidence,’ said the partisan Liggett, as if trying to send the Brit subliminal messages.

Then, as they approached a sweeping left bend, Millar took flight. He stood up on the pedals and accelerated into the crowd, his bike swinging violently from side to side, his body bobbing up and down with urgency, releasing all that pent-up energy in a bid to shake off his companions, now down to two, a Frenchman and a Dutchman. Neither reacted; if anything, they seemed relieved to see him flee, glad of an excuse to slow down. Ahead of them Millar forged on, relaxing into that gentle, easy rhythm. In the commentary box, Liggett wasn’t so calm: ‘He’s not a big-headed man at all, but when you speak to him confidence oozes out of him.’ Several times he highlighted the incongruity of a cyclist from Glasgow excelling amid such company, and in such terrain. ‘He was a little worried that this stage wouldn’t be hard enough for him,’ Liggett added with a chuckle.

Inside the final kilometre of the 226.5km stage, Millar’s hand dipped inside the back pocket of his jersey and emerged clasping a white cap bearing the name of his team sponsor, Peugeot, which he then stuck on his head in one fluid movement. ‘The little man from the Gorbals with the big heart and the powerful legs,’ screamed Liggett, his voice crackling with emotion, as Millar climbed towards the finish. ‘Millar has unleashed all his anger today on the Tour de France.’

Behind Millar, Luis Herrera and Pedro Delgado, late attackers, had leapfrogged his earlier companions; he had escaped at just the right time. But now they were chasing, and closing. They were within a minute; Millar had to sprint as if he was launching his initial attack all over again. But in the final metres, when he knew he had won, Millar appeared to relax, sitting upright, taking his hands off the handlebars, raising them, allowing his clenched fists to fall behind his head, then pumping them back into the air, palms open, eyes looking down rather than at the photographers, but face smiling. The clock stopped at seven hours, three minutes and forty-one seconds as he crossed the line. Seven hours! And he was sprinting! Uphill! It was inconceivable.

Then, his peaked cap framing his gaunt face, giving him the appearance of a jockey in need of a good feed, Millar faced what was for him the bigger ordeal: the post-race interview. Liggett asked the questions. What had gone through his mind on that final climb? ‘That I was gonna win, that I knew I was gonna win, and that I was really happy,’ mumbled Millar, wearing a blank expression apart from the thinnest of smiles forming on his lips. He had known virtually the whole stage that he was going to win, he added, and he was certain after the climb of the Col du Portet d’Aspet, when he was the strongest in the leading group. At the end of each sentence he seemed to add an ‘eh’ – virtually the only trace of a Scottish accent in his curious hybrid drawl. He proved as fascinating to watch during this interview as he had been during the race. He was a mass of contradictions, appearing self-assured yet nervous; possessed of steely confidence yet impossibly shy; in control yet awkward. He spent much of the interview looking away from the camera, away from his interrogator, but when he briefly glanced up his eyes burned with intensity. Or was it anger, as Liggett had suggested? At the same time his face twitched and his brow contorted with apparent nervousness.

Cycling became my sport, Robert Millar my hero. His seemed to be the ideal identity for a displaced young Scot to assume in a strange foreign land: suitably different, possibly cool, certainly interesting. I was given a glossy coffee-table-style book, The Fabulous World of Cycling 1984. I still have it, though some of the pictures are missing, sacrificed to the covers of school jotters. I also wrote a letter:

Dear Jim,

Please will you fix it for me to go cycling with Robert Millar, the Tour de France cyclist from Glasgow. I thought that, as a former Tour of Britain cyclist, you might look kindly upon my request.

Thank you.

Kind regards,

Richard Moore, 11, Cheshire (originally from Edinburgh).

Ordinarily, Jim’ll Fix It fulfilled children’s dreams of singing with Duran Duran, or playing football at Anfield. A plea to go cycling with a star of the Tour de France was, I fancied, sufficiently unusual to interest Jimmy Savile, who, after all, and as my dad pointed out encouragingly, really had been a Tour of Britain cyclist himself. There was no response.

What I didn’t know at the time was that Millar had a reputation for being prickly and difficult. He also had a reputation for not always obliging fans seeking autographs or photographs, far less an approach from an eccentric, cigar-puffing, tracksuit-wearing children’s TV personality. Sometimes he would politely refuse; more often the response would be a more direct ‘fuck off’. As one of Millar’s former managers noted, ‘The challenge with Robert was to get him to tell people to fuck off in a courteous way.’ Yet Millar was – is – nothing if not a walking, (occasionally) talking paradox. He could also, as countless people will testify, be obliging, generous and funny, specializing in a wry, dry and often black sense of humour.

My first real-life encounter with him was in January 1988, when he returned to Scotland for a hotly anticipated ‘Robert Millar Training Weekend’. For this camp, intended to help his aspiring young countrymen, Britain’s greatest ever cyclist gave his time freely, asking only for travelling expenses. And, as a committed vegetarian, for enough beans and toast to last him the weekend. When Millar appeared in Stirling it represented the first real opportunity for the latest generation of hopeful (as well as some pretty hopeless) young cyclists to learn from someone we all aspired to emulate – and in one or two cases, judging by the hairstyles and contrived reticence, actually to be.

At that first camp there was massive disappointment when we learned that he couldn’t accompany us on training rides because he was recovering from a minor operation in a place ‘where it affects cyclists most’, as it was reported. ‘Where the sun don’t shine’ would also have been accurate. The next year he was back, and fit. Towards the end of the first training ride I found myself splashing through puddles on back roads near Stirling in a small group of five riders that had become detached from the larger groups. One of the riders in the group, even smaller than he looked on the television, was Robert Millar. We took it in turns to ride at the front alongside him. But when it came to my turn, and my front wheel drew level with his, a very strange thing happened. Fate, or a gust of wind, intervened. My woolly winter training hat was whisked clean off my head, and deposited in a puddle. I don’t think Millar had seen that one before. He kept his cool, but half turned and said, almost inaudibly, ‘A wet hat’s better than no hat, eh?’ To which I nodded silently before peeling away from the group to go back and get it.

The chance to ride alongside Millar had disappeared in a freakish puff of wind. All those questions loaded with self-interest – How many miles should a 15-year-old ride in a week? What races should a 15-year-old aim for? If you’re going to turn professional, how good should you be at, say, 15? – would have to wait.

But not for long, because the training ride was followed by a question-and-answer session. We shuffled nervously into a lecture theatre, and then Millar appeared. The questions flowed, while Millar’s eyes darted around, rarely focusing on his audience. His answers were brief and to the point, and they were characterized by that steely assurance that seemed so at odds with his diffident manner. Most of the questions, inevitably, were about the Tour de France. Millar looked a little puzzled. ‘I think you should ask some different questions,’ he said in that curious mid-Atlantic-Scottish-French accent, wearing that half smile. ‘None of you are riding the Tour de France, so I don’t think it’s relevant me talking about it, eh.’ That was us, a roomful of teenagers, told. He did have a point though.

Nine years later, three years after his retirement, he managed the Scotland team in the Prutour, the nine-stage Tour of Britain. I was in that team, and my abiding memory is of Millar as shy, friendly, modest, with a vast knowledge of the sport, and almost always ready with a witty, often dark one-liner. Perhaps he was too shy to be a truly effective manager. But that was handy in our case: we were rubbish.

There was an incident before the start of one of the later stages. One of the Scotland riders had misplaced his race numbers. This was a disaster: without them, he wouldn’t be allowed to start. The rider in question was infamously disorganized, always late, always leaving something behind at the hotel. Yet with barely a minute left before the start, the numbers miraculously appeared … from where Millar had hidden them. He smiled that thin smile as he handed them over and said nothing. The rider got the message.

There is no debate over whether or not Robert Millar is Britain’s greatest ever Tour de France cyclist – and that, in many people’s eyes, makes him Britain’s best-ever cyclist. Supporters of Tom Simpson, the Englishman who died on the slopes of Mont Ventoux during the 1967 Tour de France, might disagree. But Simpson was a one-day specialist: he excelled in the ‘classics’ and the world road race championship, which he won – the only British rider ever to do so – in 1965. Millar, on the other hand, was a man for the major tours, of France, Italy and Spain. For many, these three races are the pinnacle of the sport, and in these events Millar stands head and shoulders above any other cyclist from these islands, which is not bad for someone who grew up in Glasgow, whose frame extended (when he wasn’t crouched over his bike) to five feet six inches, and who tipped the scales at just nine stone.

Millar was an outstanding cyclist, clearly, but he also had style and class. He was cool, enigmatic, aloof, and quietly determined. His obsessive quest for perfection was awesome. It could be quite terrifying, too. After one stage of the Tour de France the television cameras caught him removing his racing jersey to reveal a painfully skinny upper body, arms as brown as barbecued steak, and torso, with ribs protruding, translucent white. ‘Ooooh,’ said my mum, recoiling in horror. Not mock horror. Everything about him – his self-contained manner, his appearance – screamed absolute dedication, and of an extreme way of living.

When, in the early 1980s, Millar emerged as one of the world’s leading cyclists, his sport, to most in Britain, was as colourful, intriguing and impenetrable as a foreign language, and those who enjoyed it were fed only on scraps of coverage. It couldn’t have been further removed from the arenas where we traditionally watched and enjoyed sport: football grounds, athletics tracks, tennis courts. The Tour de France was on another scale; it belonged in a different dimension; it represented something other, something more, than sport. You didn’t enjoy the Tour de France, you marvelled at it. The mountains, especially, were where the Tour de France was transformed from being merely a sport into something bigger, more significant. And it was here, in the thin air and against the jagged backdrop of the Alps and the Pyrenees, that Millar excelled. His gifts in such an environment, his ability to dance with smooth grace up such steep mountains, seemed an extravagantly, exotically impressive, not to say surreal talent for somebody raised in one of Europe’s most industrialized and impoverished cities. The Tour’s profile in Britain increased throughout the 1980s, thanks in large part to the growing impact of English speakers such as Millar.

There are those who claim that in his apparent desperation not to engage with the media, Millar was his own worst enemy. Many said that he lacked charisma; others complained that he had no personality. They were wrong. He was the Morrissey of the sporting world: enigmatic, complex, sardonic; unconventional yet cool; hopelessly shy but at the same time absolutely sure of himself. Oh, and a vegetarian. Confidence, as Phil Liggett said, oozed from Robert Millar, but it was a curious kind of confidence. He was an outsider, always. Watching him race could be as exasperating as it could be exhilarating. He lost the 1985 Tour of Spain on the penultimate day, having been the outstanding rider in the race, when the Spanish teams ganged up to ensure a home victory, but also, and equally importantly, to deny Millar. He was certainly alone there. At the roadside the Spanish fans held up banners expressing their contempt for the strange Scot, for the crimes of (in no particular order) not being Spanish, wearing an earring, and having permed hair. Millar was different. He rubbed people up the wrong way. The director of the Tour de France nicknamed him the asticot – maggot – of professional cycling. To professional observers he was the ‘weedy Woody Allen lookalike, with spectacles, pony tail, and balancing chips on each shoulder’; he looked ‘more like a Dickensian chimney sweep’ than a man who made his name and his fortune in such a brutal and unforgiving sport.

The career of Britain’s best-ever cyclist ended abruptly, ignominiously, and without fanfare. His French team went bust on the eve of what would have been his twelfth Tour de France, and that was it. The end. Millar disappeared.

He didn’t literally disappear, at least not at first. He hovered around the cycling scene for a few years; he was appointed British national coach, and he wrote, with flair and humour, for cycling magazines. But his spell as national coach ended just as ignominiously when he was told, less than a year into the job, that he was surplus to requirements.

In the midst of this some rumours began to swirl around Millar. Some were cruel, some were downright vicious, but they were fuelled by gossip, not least because they went unchecked by Millar. One tabloid newspaper, upon hearing the rumour that this famous cyclist might be having a sex change, camped outside his door for a week. In 2000 the story was published and Millar was, according to some who knew him, devastated. Yet, in keeping with the cyclist who had pursued his career with singular focus and stubborn self-containment, he did not respond. He said nothing.

Then he really did disappear. All his ties with the cycling world were severed. He appears to want nothing to do with the sport any more. He has next to no contact with any of the people he knew through cycling, only the occasional email – usually one or two lines, often terse, cryptic, sometimes humorous. Every year, especially before the Tour de France, hordes of people try to get in touch with Millar, wanting to speak to him about the race, or wanting him to write about it. If they ever manage to reach him – and email is the only known method – he doesn’t respond.

Initially I felt a little uneasy about trying to find Robert Millar – not just the Millar of today, but the young Millar who grew up in Glasgow; who in his teenage years sought escape on his bicycle; who finally left the city for good, and used his bike to pursue a cycling career on the continent; who lived in France, on and off, for fifteen years, most of them with his wife and son, from whom he fled when his career ended in 1995; who then went to England, where he lived for several post-retirement years before disappearing from the sport and the public spotlight. Perhaps my unease came from the oft-stated understanding that you should never meet your heroes, far less try to write a book about them.

Nevertheless, I made email contact with Millar through a third party, one of only two people I knew who were still in very occasional contact with him, and who were as exasperated as others by his apparent ‘disappearance’. In the initial email I floated the idea of a book, and ended with this: ‘Modesty might prevent you from agreeing that such a book is overdue, but I hope you will be happy for me to progress with the project … in any case, I’d like to hear your initial thoughts.’ I wasn’t seeking Millar’s approval exactly because I didn’t think he’d willingly endorse a book, but the response, through the third party, was surprisingly positive. By which I mean that he didn’t tell me to fuck off. Yet all it amounted to really was that he knew I was trying to write a book. He let it be known that he did not object to – or, as he put it, could not stop – a book being written about Robert Millar the cyclist. But a book about Robert Millar the cyclist was not really what I had in mind. I wanted to know what Millar was like, where the dedication (or anger) that drove him to the top of world cycling had come from. It was Robert Millar the person I really wanted to get to know.

I met people, and spoke to them about Millar. Many said the same things. Yes, he was a bit strange, eccentric, stubborn, likeable when you got to know him – and special, that was the word that kept being repeated. I lost count of the number of times a former team-mate said ‘Robert’s special’ with a knowing, enigmatic smile. Naturally, this only made me more curious, but also slightly wary. It was a euphemism, but for what?

Then I travelled to Ninove, in Belgium, to see Allan Peiper, one of the more thoughtful and articulate of Millar’s former team-mates. Initially Peiper didn’t adjust well to retirement, as he explains in his autobiography. But after staring into the void of life after cycling and eventually finding a new sense of purpose, it was clear that he had been thinking quite a bit about Millar too. ‘Rob was very intellectual compared to most cyclists,’ said Peiper. ‘He thought about life and had it figured out, to some extent, but that didn’t make him any less complicated. There was anger inside him. It’s the same with a lot of top sportsmen, especially top cyclists. They have some emotional chinks that create the drive to want to be good. Whether it’s Lance Armstrong growing up in a trailer park, or Robert Millar growing up in Glasgow, I think for a lot of us there was a definite cause there, something that caused them to be angry. Something that made them need to succeed and prove themselves. Or just be accepted.’

For some reason, Peiper’s words, and his obvious enthusiasm for the task of trying to decipher the character of his old team-mate, fired my own enthusiasm. Somehow, talking to Peiper also made me less wary, less scared of the task of trying to unravel the Robert Millar enigma. I returned to my hotel room and wrote a second email, hoping that he would reply to this one directly.

Hi Robert,

I wanted to finally email you directly rather than going through [the third party] – hope you don’t mind. As you know, I’m planning to write a book about you to coincide with the Tour starting in London next year; it seems the right time given your status as Britain’s best ever Tour rider.

Over the last few months I’ve met with quite a few people who knew you growing up in Glasgow, and others who raced with you later. I’ve been putting off contacting you directly, to be honest, because, although I followed your career very closely at the time, I still felt there were gaps in my knowledge. Basically, I didn’t want to ask daft questions. However, now I feel that I’m getting there, and that I am less likely to ask daft questions. I really wanted to establish contact to see how – or indeed if – you would like to answer my questions. Of course I’m aware that you may have some questions for me as well, and I’d be pleased to answer them.

For your interest I am in Belgium just now and met with Allan Peiper, who spoke with great fondness of you and sends his best.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Best wishes,

Richard.