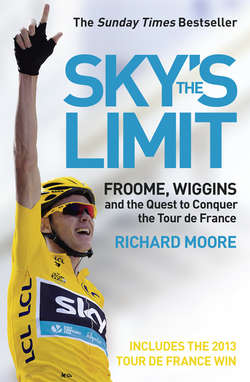

Читать книгу Sky’s the Limit: Wiggins and Cavendish: The Quest to Conquer the Tour de France - Richard Moore - Страница 7

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

GOODBYE CAV, HELLO WIGGO?

‘We’re the minions.’

Dave Brailsford

Celtic Manor, Newport, 24 July 2008

‘He’s done what?!’

Shane Sutton and Dave Brailsford were discussing Mark Cavendish. Though they found themselves in the sumptuous surroundings of Celtic Manor, the five-star golf resort in Newport, Wales, their minds were frequently in France. It was difficult for them not to be.

Cavendish, their prodigy, golden boy, natural-born winner, product of the British Cycling Academy and the rider around whom a British professional team would one day logically be constructed, had become the sensation of the Tour de France with four stage wins in his second attempt at the world’s biggest race. ‘I believe I’m the fastest sprinter in the world,’ he had said the day before the Tour started, and he had now proved it. Four times.

The cream of British Cycling thus occupied parallel universes for much of the month of July 2008. In Newport, holed up in Celtic Manor, was the British track team, now in ‘lock-down’ mode, and almost to a man and woman recording world-class times while training on the nearby Newport Velodrome, with the Olympics only weeks away. And in France was Mark Cavendish: the hottest property in world cycling.

Following stage 14, on 19 July, Cavendish abandoned the Tour in order to remain fresh and fit for the Olympics. He would ride the madison with Bradley Wiggins in Beijing, though at this point, and unknown to all but a few people, Wiggins’ participation in the Olympics was in doubt due to a virus that left him bed-bound for six days.

Brailsford and Sutton had a lot on their plate. The deal with Sky was done, and on 24 July the satellite broadcaster was announced as the new ‘principal partner’ of British Cycling. A five-year, ‘multi-million pound partnership’ encompassed every level of cycling, from encouraging participation to grassroots, to talent development, to elite; and every discipline, from BMX to mountain biking, track and road racing. The wider goal was to get Britain back on its bike – to continue a process that London’s 2007 Grand Départ may have started, of transforming the country’s cycling culture, and encouraging a million more people to ride bikes over the next five years. ‘I believe this partnership will create a step change for cycling,’ said Brailsford. ‘Working together, we can take elite cycling to new heights and get more people involved in the sport at all levels.’

The track sprinters Chris Hoy and Victoria Pendleton – both of whom would go on to win gold medals in Beijing, in Hoy’s case three – fronted the launch of the Sky partnership. There was no mention of the sponsorship extending to a professional road team.

But Brailsford and Sutton both knew – despite their later assertions to the contrary – that the partnership with Sky was a forerunner to a professional team. Wiggins knew. And Cavendish knew. All were clear, too, that Cavendish would be the leader, the talisman; the fulcrum of the new team, the plans for which Brailsford had brought forward. In Bourg-en-Bresse he identified 2013 as the likely launch date, following the London Olympics. Yet in May 2008, as negotiations progressed with Sky, Brailsford revised that: the team would hit the road in 2010, he said.

Cavendish’s four stage wins at the Tour, which followed two stage wins in the Giro d’Italia, confirmed the wisdom behind a plan that would see Britain’s first major league professional team led by the world’s best sprinter, and most prolific winner. One of Brailsford’s trump cards was Rod Ellingworth, Cavendish’s coach. Cavendish rode for Bob Stapleton’s Columbia-High Road team – a new team that Stapleton, the Californian millionaire, had salvaged from the ashes of the old T-Mobile outfit, later to become Columbia-HTC, then HTC-Columbia. But Ellingworth was still the man Cavendish turned to, still the big brother figure, who managed his training and gave him tactical coaching. Ellingworth was also the man who, when Cavendish was at the Academy, instilled in him the understanding that, in order to win, he had to lead; and that in order to lead, he had to act like a leader. It meant accepting the responsibility, and handling the pressure, of having eight teammates sacrifice their own chances for him. ‘There aren’t many who can take on that responsibility,’ says Ellingworth. ‘But Cav can.’

But in the run-up to the Tour, and before the British Olympic team departed for the Newport holding camp, Cavendish and Sutton, both combustible characters, had one of their fairly frequent bust-ups. It owed to Sutton’s repeated assertions, in public and in private, that Cavendish would lead the new British team. Cavendish took exception to the assumption. He felt his involvement was being taken for granted. The upshot was that Cavendish travelled to the 2008 Tour in a fiery, belligerent frame of mind. ‘Shane had bawled him out and Cav was asserting his authority,’ as one insider puts it. ‘The team was to have been built around Cav. But he went to the Tour with a “fuck you” attitude towards Shane and British Cycling.’

And it was this, perhaps, that proved decisive when, midway through the Tour, Cavendish was offered a new two-year contract by Stapleton. It was a contract that would also give his team an option on a third year (taking him into 2011), and it was worth €750,000 a year. When it was offered to him, Cavendish signed it. He told no one.

‘He’s done what?!’

Brailsford and Sutton were walking across the Celtic Manor golf course when they found out. Cavendish, having arrived in Newport, admitted a little sheepishly to having signed the new contract. When Brailsford and Sutton found out, their reaction was one of shock, disbelief and horror. It would mean – after Beijing – going back to the drawing board.

Then there was Wiggins. In what could almost be a metaphor for his and Cavendish’s respective status at the time, while Cavendish was basking in the glory of having won four stages in the Tour, Wiggins was bed-bound fighting a virus.

And when Wiggins wasn’t ill, Sutton, who had long acted as a father figure to him, was keen to persuade him to commit to the new team, too.

Wiggins was by now a teammate of Cavendish’s at Columbia-High Road. They had ridden together at the Giro in May, Wiggins as a member of Cavendish’s lead-out ‘train’ – the group of teammates that organised themselves at the front in the closing kilometres, forming a team pursuit-style line, with Cavendish positioned at the rear, ready to unleash his sprint in the final 200 metres. It was the kind of riding in close formation, and the kind of fast effort, that Wiggins was brilliant at. Great track rider that he was, he was blessed with the speed and bike-handling skills that only come from hours spent riding in circles around a velodrome. No question, he could be a valuable member of Cavendish’s train. And in some respects that made sense for Wiggins, too. At the Giro he appreciated having a specific role and an actual job to do – something he hadn’t had in his French teams. But there was a problem: Wiggins did not want to become a member of Cavendish’s train in a team that he feared would become ‘the Cav show’. He did not regard that as ‘career progression’.

Wiggins was attracted to the idea of joining David Millar’s Slipstream team. While with High Road he could only see a future as a bit part player in the Cav show, with Slipstream (re-named Garmin-Slipstream on the eve of the 2008 Tour) he would be freer to do his own thing (whatever that might be – Wiggins wasn’t sure). Garmin offered Wiggins a two-year contract worth €350,000 a year – around €200,000 a year more than he was on at High Road.

And so in Newport, as well as having to fight a virus, Wiggins faced a dilemma. With the Olympics approaching, and Wiggins very publicly aiming for three gold medals – in the pursuit, team pursuit, and finally with Cavendish in the madison – there was always the possibility that success in Beijing could increase his earning power. Then again, in the world of professional road cycling, Olympic track medals might be worth a little, but not very much. In the meantime, the offer from Garmin was good, the security of a two-year deal appealing; but Sutton urged Wiggins not to sign – or to sign for only one year. Brailsford even showed him a fax from Sky, to prove the money would be there to set up the team.

But, to Wiggins – with his wife, Cath, and their young family also weighing heavily on his mind – requesting one year instead of the two on the table from Garmin seemed counter-intuitive. His career to date, in which he’d resolutely focused on pursuit racing for the best part of a decade, suggested he was not, by instinct, a risk-taker. Now, as he prepared to fly to Beijing, probably did not feel like the time to start gambling. He had to make a decision before the Olympics. So in Newport, in early August 2008, Wiggins agreed to spend the next two years with Garmin.

In Beijing, Brailsford and his team were lauded. They won as many gold medals – eight – as Italy won across all sports, and one more than France. Wiggins won two of the three gold medals he’d set his heart on, with the only disappointment – indeed, the entire team’s only disappointment – coming in the madison. There, a tired Wiggins, riding his third event, failed to fire, and he and Cavendish were never in the race, finally finishing ninth. Cavendish ended the meeting as the only British track cyclist not to win a medal; and he was disgusted, saying he felt ‘let down’ by Wiggins and by British Cycling. He wished he’d never pulled out of the Tour de France.

Lanesborough Hotel, London, February 2009

‘Morning, gents,’ says Dave Brailsford. There are handshakes all round. Then Brailsford sits down and six journalists form a crescent around him, settling into comfortable chairs in a drawing room on the ground floor of one of London’s plushest hotels. The Lanesborough is a striking yet understated cream-coloured building overlooking Hyde Park, with Bentleys and Rolls-Royces, engines purring, permanently stationed outside.

There is a slightly awkward silence. Brailsford, in a navy blue British Cycling Adidas tracksuit top, blue jeans and trainers, is flanked by four men wearing smart suits and ties and polished shoes. One of them introduces Brailsford as the performance director of British Cycling. But we know that. Everyone in Britain now knows that, with Brailsford elevated to the status of sporting guru, and named coach of the year at the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Year awards (even though Brailsford is not, and never has been, a coach). He has been visited by Sir Alex Ferguson and his coaching staff at Manchester United; other sports are keen to speak to him, to hear his secrets. Ferguson had sat with Brailsford and Shane Sutton in the former’s office at the Velodrome, with Brailsford quizzing the great football manager on his knack of successfully re-building teams as players became old or ineffective. ‘Just get rid of the c**ts,’ Ferguson told him.

The invitation to come to the Lanesborough had come by phone only 48 hours earlier: ‘Be at the Lanesborough Hotel at 10.’ But we weren’t told why, and nor were we to tell anyone that we’d been invited to a meeting whose purpose we didn’t know.

The low winter sun cuts across the room, glancing off Brailsford’s head, forcing him to squint. ‘Well,’ he begins. ‘Thanks for coming to this … em, gathering.’ Then he spreads his hands and says: ‘We’re here to announce Britain’s new pro team, and the identity of our sponsor. Sky.’

The dam breaks; and now Brailsford quickly gets into his flow, rubbing his hands enthusiastically, forming them into descriptive shapes. ‘My world changes from today,’ he says. ‘This is new, it’s something people haven’t seen before. We’re setting out to create an epic story – an epic British success story. Now it’s down to business: to find out what it’s going to take to win the Tour de France with a clean British rider.’

What will the team be called, Brailsford is asked. He seems to hesitate. ‘It’ll be Team Sky. Yeah, Team Sky.’

And what will the budget be? The men in suits fidget. ‘Enough to be competitive,’ says one. ‘Enough to achieve our ambitions,’ says another. Brailsford smiles and shakes his head at the suggestion that they will be the Manchester City of professional cycling – the football club made newly wealthy thanks to an influx of Arab money.

‘It’s a bit like fantasy football, or fantasy cycling, at the moment,’ says Brailsford when asked how far advanced he is in assembling, from scratch, a squad of around 25 riders. ‘It’s a lot of fun. We’ve had some fantastic discussions. And we have created a monster database of the top professional cyclists. But at the end of the day it’s like Moneyball: it’s all about doing your homework.’

But what about his aim of winning the Tour with a clean British rider? Never mind Britain’s record in the race – three top 10 finishes in 105 years – there is the ‘clean’ part of the equation. Given cycling’s tarnished image, is that possible? ‘The perception of cycling is changing,’ says Brailsford. ‘We need to be agents of change. Our job is to prove beyond doubt that it can be done clean. The legacy of that would be phenomenal.’

Brailsford’s mention of Moneyball is interesting. Moneyball is the 2003 book by Michael Lewis – subtitled The Art of Winning an Unfair Game – in which the author spends a season following the Oakland Athletics (A’s) baseball team, which consistently punches above its weight, outperforming teams with far bigger budgets. What Lewis discovers, while shadowing the coach Billy Beane and his backroom team, is that the A’s have developed a system of recruiting and assessing players that flies in the face of received baseballing wisdom, but which works – and works spectacularly.

The intricacies of Beane’s system are too complicated to go into here. One of the central points, though, is that Beane, despite having been a player himself, has done what most insiders in most sports are unable to do; he sees his sport in a fresh, objective way, de-cluttering himself of the experience, prejudices, conventional wisdom and knowledge that tend to be accumulated from years of involvement. He is an insider with an outsider’s perspective. Lewis notes that one of Beane’s key appointments is a Harvard graduate, someone who has never played professional baseball. Which is a point in his favour, according to Lewis: ‘At least he hasn’t learned the wrong lessons. Billy had played pro ball, and regarded it as an experience he needed to overcome if he wanted to do his job well.’

This is interesting in the context of British Cycling, and it’s easy to see where Brailsford is coming from. For he, too, is an ‘outsider’ in the world of professional road racing. But it also chimes with something Chris Boardman had told me. For some time now the former professional’s job at British Cycling had been to head up the research and development department, the so-called ‘Secret Squirrel Club’. It was Boardman’s department, or the team of people he oversees, that developed the bikes and equipment used by the British team at the Beijing Olympics, including the rubberised skinsuits which, as soon as the Games were over – and in an example of Brailsford’s attention to detail – were recalled and shredded, in case a rival nation got their hands on one and managed to copy them.

In selecting his team of people, Boardman had said his priority was to select those who knew nothing about cycling or bikes. ‘There is no one with anything to do with cycling involved in equipment research and development.’ And so they were drawn from Formula One and the world of engineering. Boardman’s premise was simple: ‘Preconceived ideas kill genuine innovation.’ He encouraged his team to ask questions which would seem, to anyone involved in the sport of cycling, obvious or even stupid. ‘It takes a bit of self-discipline on my part,’ Boardman said, ‘to work out whether we’ve reached a dead end with someone, or if I’m stopping [innovation] with my preconceived ideas.’ Clearly Boardman regarded his own background, as Olympic and world champion, and Tour de France yellow jersey wearer, as ‘experience he needed to overcome if he wanted to do his job well’.

Another thing about Moneyball, though, is its emphasis on statistics. This is perhaps what Brailsford was more particularly alluding to in the Lanesborough, especially when he mentioned his ‘monster database’. In assessing players, Beane used ‘sabermetrics’; that is, the analysis of baseball through objective, statistical evidence.

Brailsford appears to want to do a similar thing in road cycling, using statistics and science – as he has done so successfully in track cycling. This would be a new approach, with professional road cycling as traditional as they come, its teams run by former professional riders, who then hand over to other former professional riders, who then … etc. The pool of people is small; almost, you could say, incestuous.

Brailsford, as he hinted in Bourg-en-Bresse when lamenting the way many teams seemed to be organised and run (‘they don’t even know where their riders are between races – that’s bonkers!’), has perhaps identified this as a weakness; or a ‘market inefficiency’, to use the language of Michael Lewis in Moneyball. Weaknesses and market inefficiencies create opportunities. If a scientific approach doesn’t seem to be adopted by other teams, it could be for two reasons: because it doesn’t work; or because it hasn’t been tried.

There are good reasons for suspecting it might not work. Unlike track racing, which takes place in a relatively controlled and predictable environment, road racing is multi-dimensional and unpredictable. The variables – in weather conditions, the nature of the course, the presence of up to 200 other riders and 20-odd teams – are numerous, even before we begin to decipher some of the unwritten rules and etiquette of the peloton, or the unofficial alliances and ‘deals’ between riders and teams, which are rumoured to be commonplace.

From a performance point of view, how you evaluate and assess road cyclists seems, in some respects, as complicated as the Enigma code. No analysis can be based simply on finishing positions, for example, since that tells only a fraction of the story. In fact, it might tell nothing of the story. Good teams need good domestiques, for example. But how do you evaluate a rider whose job it is to look after his team leader? By the number of water bottles he has distributed? By the length, and quality, of the shelter he has provided? What you cannot do is ‘measure’ the effectiveness of a domestique by his order across the finish line. Indeed, it is entirely feasible, sometimes desirable, that a domestique does an outstanding job and then doesn’t finish the race.

Still, if a more science-based approach hasn’t been tried, all the more reason to try it. It would be remiss of Brailsford not to at least explore the possibility. Like Boardman, Brailsford has successfully engaged ‘outsiders’ – in particular sports scientists with no previous experience in, or knowledge of, cycling – asking them to look afresh at the sport; to ask questions too obvious to be put by ‘experts’; to identify ‘market inefficiencies’.

But a key member of Brailsford’s team has helped in another crucial area, giving his athletes – and indeed coaches – the mental ‘tools’ to think logically rather than emotionally.

‘It’s not about switching off emotional thoughts, because that would be impossible,’ says Steve Peters, the psychiatrist employed by Brailsford, and now a member of his senior management team, along with Shane Sutton. (Boardman, who had been the fourth member of that team, stepped down after Beijing.) ‘It’s about bringing emotional thoughts under control,’ continues Peters, ‘overriding them with logic.’

Peters works with many athletes across many sports, and one of his techniques is to help them identify, and isolate, their ‘chimp’ – their ‘chimp’ being the emotional part of the brain. Each of the gold medallists in Beijing spoke with fear of being ‘hijacked by my chimp’. They rode in fear of their chimp; or, rather, they rode with their chimp caged. Chris Hoy, the sprinter, said that his tears on the podium after his third gold medal owed to the fact ‘I’d kept my emotions in check for the whole five days of competition; that was it all finally coming out.’ The tears were the doing of his chimp, unleashed from its cage and running amok.

Also central to Brailsford’s modus operandi – and the phrase for which he became best known following Beijing – is his ‘aggregation of marginal gains’. In fact, Billy Beane in Moneyball is similarly preoccupied with taking such a detailed, no-stone-unturned approach. There is another name for it: Kaizen, the Japanese philosophy of constant and continuous improvement.

John Herety mentioned the ‘empowering’ aspect to Brailsford’s management style when he took over from Peter Keen as performance director at British Cycling. This is Kaizen in action: it hands responsibility to everyone within an organisation; from the cleaner to the CEO, everyone is encouraged to participate in the organisation’s activities, and to think about and improve their performance. It doesn’t have to be a big improvement; just marginal ones. ‘We encourage everyone to make a 1% improvement in everything they do,’ Brailsford explained. ‘Everyone, from the mechanics sticking on a tyre to the riders; their eating, sleeping, resting; everything.’

Central to Brailsford’s ‘aggregation of marginal gains’ and Steve Peters’ training of athletes to keep their emotional chimp under lock and key, is a focus on the process. The process is everything. ‘There’s no point in looking at consequences, because they could be out of your control,’ says Peters. ‘All you can do … all you can control is the process.’

Brailsford and his team – or most of it – bought into this in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics. Bradley Wiggins, by publicly admitting he was aiming for three gold medals, might have been an exception. When Wiggins failed to do this – winning ‘only’ two – he seemed slightly disappointed. (Speaking to Peters after the Olympics, he alluded to this in passing, when talking about the difficulties the non-medal winning cyclists were having post-Beijing: ‘It’s awful for Brad. He did his best and was superb. Double gold – unprecedented, until Chris [Hoy] got his three!’)

Brailsford didn’t make that mistake. In the run-up to Beijing, and even while the Olympics were on and his cyclists returned with gold medal after gold medal, he steadfastly refused, despite being asked repeatedly, to be drawn into predicting how many golds his team might end up with.

It is this that makes one aspect of the mission statement that Brailsford outlines at the Lanesborough Hotel puzzling, more particularly because it is the big one: the one that will make all the following day’s headlines. That stated goal, to win the Tour de France, seems to fly in the face of Brailsford and his team’s usual approach. It’s an outcome, not a process.

‘Control’ appears to be another important word to Brailsford. It is a big reason for him wanting to run a professional road team, to bring his top athletes back under the umbrella of British Cycling, to be able to call on them for events – world championships and Olympic Games – in which they compete for the national team, rather than being at the mercy of their pro teams.

As Brailsford now knew all too well, with riders scattered around Europe, ‘control’ could be difficult to exert even when British riders raced in GB colours. The 2005 World Championships in Madrid had proved that, while also revealing some of the murkier aspects of professional road racing – including the deals and unofficial alliances previously alluded to.

In Madrid, two British riders – Tom Southam and Charly Wegelius – puzzled observers, and indeed the British coaching staff, now headed by Brailsford, by working at the front of the peloton in the early stages of the race. Their efforts were considerable, and did not appear to be in British interests. But there was a good reason for that: they weren’t. Though wearing British jerseys, the two were actually working on behalf of the Italian national team.

John Herety, the road team manager at that time, now explains: ‘Tom and Charly told me there was the potential for it happening.’ Southam and Wegelius both rode for Italian professional teams. ‘They were told it’d be in their interests to ride for the Italians. Their motive was not financial, I’m sure of that – it was to keep in with the sinister group of riders who ran cycling in that area [in the north of Italy]. They were looking after their jobs. I didn’t like it, I was uncomfortable with it, but …’ Herety, who’d ridden as a professional on the continent in the 1980s, and managed teams since the early 1990s, understood the rules of the game, and that, at the world championships, riders from ‘lesser’ countries would be encouraged, perhaps even obliged, to ride for the country in which they plied their trade professionally.

As Southam explains: ‘In any other world championship, up to that point, it would have been the correct thing to do [as a British rider]. It was based on career. I can’t speak for Charly, but he was very embedded in Italian culture. His contemporaries, the people he trained with, were in the Italian team. These were the people he worked with and who influenced his career. For me, I was in my second year, I was trying to break into that … circle of riders. I thought I needed to show these guys what I could do.

‘The suggestion made to us at the World Championship the previous year was that we should make the most out of this race: to do the best we could for our careers. And I went into Madrid with the same attitude, but the climate had changed and I didn’t take that into account. Like I say, in any other world championship it would have been the correct thing to do …’

When Southam says ‘the climate had changed,’ he is referring to Britain’s rising status as a world cycling nation, even if this still owed only to their success on the track, particularly at the previous year’s Athens Olympics. As Herety explains: ‘One of the big things Dave was trying to create was this belief that we were just as good as everyone else – the Aussies, the Italians, the French, Belgians, Spaniards. This kind of thing had been going on in cycling for years and nobody cared. But the environment was definitely changing. Britain was trying not to be seen as second-class citizens. And so Dave had to be seen to be doing the right thing.’

While Southam and Wegelius were told off (Brailsford phoned Southam in the week after the road race. ‘He wasn’t unpleasant,’ says Southam. ‘He just said, “You fucked up”’), the furore that followed Madrid was such that Herety offered to resign as British Cycling’s national road manager. ‘I was hoping they’d say no,’ he says with a bitter laugh. ‘But they said, “Okay, then.”’

The ramifications of what happened in Madrid were far-reaching, while the episode also provided further retrospective vindication for Peter Keen’s original decision not to pour resources into road cycling. Never mind the drugs, it was murky in so many other respects; a game played to its own rules, in a bubble that could resemble a mafia state.

Although Brailsford didn’t allude to Madrid when discussing his plans for Team Sky, a key motivation, surely, was to ensure that such a thing didn’t happen again. Running his own team could, perhaps, allow him to control what at times seemed uncontrollable.

Martigny, Switzerland, 21 July 2009

Dave Brailsford and Jonathan Vaughters are standing together, but apart from the crowd, in the Village Départ of the Tour de France, locked in conversation. In less than an hour stage 16 of the Tour de France will get underway from the Swiss town of Martigny, crossing the Col du Grand-Saint-Bernard and the Col du Petit-Saint-Bernard, both enormous Alpine passes, before finishing in Bourg-Saint-Maurice.

They make for an interesting, contrasting pair: Brailsford in British Cycling uniform of blue jeans and polo shirt, the quirkily debonair Vaughters, manager of the Garmin-Slipstream team, in a crisply ironed pale blue shirt, white jeans and brown suede loafers. Vaughters also wears small rectangular, subtly shaded glasses, and has long sideburns, two thin wedges extending down his cheeks towards the corners of his mouth. Since riding with Lance Armstrong in the US Postal team in the late 1990s, Vaughters has cast himself as an outsider, with an original, innovative approach. His team was set up to be different, from their Argyle-patterned strips to the anti-doping culture and the central hub – rather than being strewn across the continent, most of Vaughters’ riders live in Girona, Spain. In fact, Vaughters has perhaps stolen a march on Brailsford here. His Garmin team, with its anti-doping ethos and internal testing programme, and its centralised base (unlike other teams, Vaughters knows where his riders are in between races), is doing some of the things Brailsford said he’d do.

Brailsford and Vaughters have much to talk about. Since the pre-Olympic holding camp, in Newport 12 months ago, everything has changed, in particular with regard to Bradley Wiggins. After winning his two gold medals in Beijing, Wiggins, now riding for Vaughters’ team, turned his attention, finally, to road racing. And his aspirations seem to extend further than long, doomed solo breakaways. At the Tour’s start in Monaco he even admitted that, for the first time in his career, he was aiming for a high overall placing. By ‘high’, he said, he was thinking top 20. Privately he was thinking top 15, maybe even top 10.

Now, in the final week of the 2009 race, to widespread astonishment, Wiggins sits third overall, just behind Alberto Contador and Lance Armstrong. On the previous stage, to the ski town of Verbier, his performance was befitting his lofty placing. After his teammates David Millar and Christian Vande Velde set a searing pace to the foot of the mountain, Wiggins rode like someone trying not merely to finish in the top 20, but like someone trying to win the Tour. Here, for the first time, was the sense that Wiggins wasn’t merely surviving: he was a major player, instructing his team to set him up, then assuming responsibility for finishing the job off, taking over like only a natural-born leader – or someone at the very peak of their form and confidence – can.

In Verbier, although Contador jumped away to win the stage, Wiggins’ fifth place, in the company of climbing specialists Frank Schleck and defending Tour champion Carlos Sastre, and 30 seconds ahead of seven-time winner Armstrong, had left him in third place overall. Only four days remained to Paris. The podium beckoned.

Whatever happened in those final four days it had become clear: Wiggins had managed a metamorphosis of Kafka-esque proportions, in his case from Olympic track star to Tour de France contender. How had he done it? The loss of 7kg clearly helped – his new, pared-to-the-bone physique saw him re-(nick)named: from ‘The Wig’ or ‘Wiggo’, he was now ‘The Twig’ or ‘Twiggo’.

Whatever the cause, the implications of his transformation are enormous, especially for the two men locked in conversation in the start village in Martigny. In Newport Wiggins had signed a two-year contract with Garmin, and so Vaughters has Wiggins for the 2010 season. Brailsford, meanwhile, is in the process of scouting and recruiting for Team Sky for 2010. But he is faced with the prospect of running a British team without a British star. Mark Cavendish, on his way to following his four stage wins of the previous year’s Tour with six at this year’s race, is locked into Bob Stapleton’s Columbia-HTC team until the end of 2011. It is difficult to overstate how desperate this situation is. Wiggins and Cavendish are proving two of the stars of the 2009 Tour, both are British, but neither is available to Brailsford’s new British team.

Eventually Brailsford breaks off from Vaughters and stops to talk. He describes rider recruitment as ‘like a game of poker at the moment’.

‘It’s a fluid, dynamic situation,’ says Brailsford. ‘I’ve been sitting there with my budget most nights, rejigging it on an hourly basis almost, thinking, shit, we can do this, we can’t do that. I think we’ve filled 17 slots. We’re getting down to the sharp end now. The element of poker is the question: should we wait to the end of the season and see if any teams collapse, and get some top riders cheap?’

Brailsford describes the ‘intelligence gathering’ he’s been doing, which seems to refer mainly to sussing out whether riders can be trusted; whether they are ‘clean’. Indeed, there is a rumour that one prominent rider has been turned down on the basis of suspect data on his biological passport. Brailsford won’t confirm this. ‘It’s not a black and white science,’ he says of the analysis of the passports, which monitor a rider’s blood and hormone levels over a long period. There is a margin of error, so I can’t say for certain that so-and-so is using drugs. But we’re taking a no-risk approach.

‘When I talk to every agent,’ explains Brailsford, ‘the first thing I want is consent to see their biological passport. I get all the data sent over to Manchester to get our experts to pick over it. We also look at the history of the guy, his progression over a number of years. All the best bike riders, the clean ones, you see steady progression; you can graph it. The ones whose performances go up in a spike usually test positive. There are no secrets. It’s basic stuff; intelligence gathering.

‘But yeah, some of the data that comes through – you think, Jeez! I wouldn’t say I’m surprised. It just makes me laugh, the audacity of some of them. But like I say, we’re taking a no-risk approach.’ (I later learn more about one suspect case from Shane Sutton. The rider in question, a top one-day rider, had been offered a contract at the Milan-San Remo Classic in March. ‘Then we looked at his [biological] passport,’ said Sutton. ‘It was all over the place. We just said, “Sorry, mate, see you.”’ The rider in question subsequently found a place on another big team: possibly a disturbing outcome; or perhaps Brailsford and his team misread his passport. As he says, it’s not an exact science.)

Brailsford admits he’s been stung by the reaction in some quarters to his stated ambition of winning the Tour with a clean British rider. On both counts, ‘British’ and ‘clean’, he has been accused of naivety. ‘Everyone says it’s impossible to win the Tour clean,’ says Brailsford. ‘It’s been said for a while now. I don’t know whether these people think we just stick our heads in the sand in Manchester. We’ve got some of the best sports scientists in the world. And we use that knowledge and do our homework: we don’t just come out with irrelevant comments.

‘I think Brad’s a case in point,’ he continues. ‘Bradley Wiggins is clean, and he’s here performing with the best in the world. Correct me if I’m wrong, but he could win this bike race. He hasn’t changed into a new athlete. He’s the same person, taking the same full-on approach to another discipline within the sport. It vindicates our idea that if you take a proper approach – analysing everything, looking at the sports science – then it’s possible.

‘To be honest,’ Brailsford adds, ‘for the last couple of years I’ve been quite confident we’d get a British winner of the Tour de France, and people have said, “Yeah right, you don’t know what you’re talking about.”’

And is Wiggins one of the riders he had in mind as a potential winner?

Brailsford, now standing with his arms folded like a football manager, rocks back on his heels and, with his mouth clamped shut, shakes his head. ‘No, no,’ he says. ‘No, no, no.’

What had he and Vaughters been discussing? ‘Actually,’ he says, unfolding his arms, ‘we were talking about Swiss chocolate.’

Bourgoin-Jallieu, 24 July 2009

In a hot and dusty field in Bourgoin-Jallieu, where stage 19 of the 2009 Tour will start in an hour, reporters and TV crews form a crowd around the entrance to the Garmin-Slipstream team bus, close enough to catch refreshing wafts of the air-conditioning whenever the door opens. Then comes not so much a waft as a blast of something else: the raw punk energy of ‘Pretty Vacant’ by the Sex Pistols. As soon as it starts it is cranked up, prompting a sing-along inside:

‘No point in asking us, you’ll get no reply …’

The bus reverberates to the rhythm, rocking to the movement inside. Matt White, the team’s director, steps out, as if to escape the noise. ‘Wiggo will be out after this song,’ says the Australian, smiling broadly.

When Bradley Wiggins emerges, 24 hours before the biggest day of his career, with his battle for a place on the podium still alive, and set to be decided at the summit of Mont Ventoux on the penultimate day of the Tour, he steps into a swarm of reporters. It is a swarm that has grown day by day, and which is now as chaotic as the crush outside any of the other team buses, with the possible exception of Astana, the team with two of Wiggins’ podium rivals, the yellow-jerseyed Alberto Contador and Lance Armstrong. In his comeback year Armstrong would surely not have predicted he’d have to beat a track cyclist for a place on the podium of the Tour de France. Nobody would have predicted that. But Wiggins has looked strong, Armstrong vulnerable and more erratic than in his pomp. ‘Armstrong, fragile troisième,’ reads the headline in L’Equipe this morning.

The Sex Pistols are Wiggins’ choice, and that lyric – ‘No point in asking us, you’ll get no reply’ – has come to seem especially apt. The more Wiggins has grown into his new role as a Tour contender, and the more interest there has been around him, the less comfortable he has seemed. It is one reason, allied to his new star status, for the scrum outside his bus this morning: the less he said, the more prized Wiggo’s words became.

But it is in marked contrast to the Tour’s first rest day in Limoges, a week into the race, when Wiggins had been expansive, and fascinating. After his performance in the Tour’s first mountain range, the Pyrenees, everyone was talking about his weight loss, as though that held the key to his transformation. ‘I’ve worked my arse off for this,’ he said in Andorra, after finishing with the leaders at the Tour’s first summit finish. It was true: his arse did seem to have vanished.

In Limoges a few days later Wiggins explained how he’d done it, and why: ‘I went about it in a really planned way. I worked with Nigel Mitchell [the British Cycling nutritionist] and Matt Parker [the BC endurance coach]. It’s been a nine-month process and I did it because I wanted to give the road, and the Tour, a right good crack. Shane Sutton’s been telling me I could do it; he instilled that belief and confidence in me.

‘After the Olympics, and the party season and making a prat of myself for part of the year, I weighed 83kg. Now I’m 71kg. But that’s it; there’s no more to come off. It’s getting ridiculous now – Nigel’s quite worried, I think. But it’s worked very well for me. I haven’t lost any power. I’ve been lucky.

‘It’s been a lengthy process and there were spells when I could put weight on, and others when I could lose it,’ Wiggins said. ‘A lot of it was changing what I ate, and when I ate, not necessarily eating less. I’d go wheat and gluten free at times. And I’d try not to eat bread. I don’t have any sugar any more. That cuts out a lot of calories. I’d have two or three sugars in coffee. And booze – I don’t have any beer any more. I forget the last time I had a beer. You get to the point where you don’t miss it.’

At this point, Wiggins might not have been comfortable talking about himself as a Tour contender – almost two-thirds of the race remained, including the Alps and Mont Ventoux – but he appeared far from uncomfortable talking candidly and self-deprecatingly about himself, and his almost comical lack of preparation for this Tour. He hadn’t reconnoitred the stages to come in the Alps, he admitted. ‘Nah, of course I didn’t,’ he laughed. ‘I was doing 10-mile time trials and Premier Calendars [domestic road races] back in England. I didn’t really expect to be in this position.’

Yet he had believed that a high overall placing might be possible. Apart from Sutton’s encouragement, a catalyst had been the previous year’s performance of his Garmin teammate Christian Vande Velde. Vande Velde had been fourth in 2008. ‘That was inspiring,’ said Wiggins, ‘’cos I know he’s clean. It showed me you can do it on bread and water. I mean, I left the Tour in 2007 saying I’d never come back. But watching it on telly last year, seeing people like Christian and Cav, it was a breath of fresh air from the previous years.’

The biggest change, however, was in Wiggins himself. ‘I didn’t have the work ethic when I first rode the Tour in 2006,’ he admitted. ‘I was coming off the back of being Olympic champion at the age of 24, and I thought I was it, to be honest. I thought I’d made it. It’s only now I realise what cycling’s about. With the Olympics, you get swept along, they’re great, fantastic, but, in the world of cycling, they don’t mean much. You get over-feted for the Olympics.’ There were other reasons, though, for sticking to the track, to what he knew. ‘Before 2006 I was in a team that I disliked, surrounded by people that disliked me,’ Wiggins said. ‘And in 2006 I just wanted to do the Tour to say I’d done the Tour. I didn’t think I’d come back; I thought I’d lose my contract at the end of 2006, so I just wanted to say I’d done the Tour.

‘I grew up in teams where the French had a real funny attitude towards everyone else,’ he continued, now hitting his stride – getting things off his chest. ‘There was this sense of: “There’s no way we can compete with those guys because they’re doing other stuff, but we’re French and we do it right, and we have croissants and baguettes, and we can sleep at night with a clear conscience and can’t control what other people are doing.” Even if you were near the top guys on a stage, the attitude was: “That was fantastic, look how well you did.” And you were feted for doing quite little things, really.’

Joining Garmin at the start of the season had opened his eyes to a team that ‘gives you the freedom to be who you want to be. We’re much more of a family, without shouting about it. People want life contracts here. It’s just like a close knit friendship, a relaxed atmosphere, and there’s no pressure to get results, which suits me.’

As he spoke, in the dining room of a budget hotel on the outskirts of Limoges, Wiggins appeared relaxed and at ease. He slouched in his seat, his long, lanky legs splayed beneath the table, from time to time using his painfully thin arms to help make a point. He tended to avoid eye contact, however. He also remarked testily that he ‘had the arse with some journalists,’ who kept asking him about doping. ‘Lance gave me some advice about the press,’ he said. ‘But I’m not going to tell you what he told me.’

Whatever it was, Wiggins grew gradually more distant as the Tour wore on and his star ascended. Most mornings he remained in his bus for as long as possible, emerging as the last call was going out for riders to sign on for the day’s stage. Sometimes he had a few words for the waiting press; other mornings he ignored them, hiding behind his Oakley sunglasses and pushing through the crowd as he rode off silently. It was very different to 2006, when he spent mornings drinking coffee, reading newspapers, shooting the breeze. It was true that his circumstances had changed beyond recognition. But was there another explanation? One morning, I mentioned Wiggins’ reticence and occasional curtness to Jonathan Vaughters, his team manager. ‘He’s shy,’ said Vaughters. ‘It’s no more than that; he’s really uncomfortable speaking to the press because he’s actually very shy.’

‘But he’s a natural,’ I said. ‘He’s eloquent, and he can be funny. He doesn’t seem shy.’

‘I was watching him in Limoges,’ said Vaughters. ‘He was doing a good job of seeming comfortable. But it was an act. I could see his legs under the table – they were shaking.’

Hotel Cadro Panoramica, Lugano, 25 September 2009

Early evening on the roof terrace of the Panoramica Hotel, as the sun sets over Lake Lugano, which nestles deep in the valley below, and Dave Brailsford surveys a pile of white paper sitting on a table, its edges gently lifting with the breeze.

‘I can sign those while I talk,’ he says to the colleague charged with managing the logistics of setting up Team Sky.

‘I’m not sure that’s such a good idea,’ she says.

They’re the riders’ contracts for 2010. But they don’t include one for Bradley Wiggins. His fourth place in the Tour – missing out on the podium by just 38 seconds to Lance Armstrong – was sealed with a gutsy, even heroic, effort on Mont Ventoux on the penultimate day.

‘And so to the Ventoux,’ Wiggins had written on Twitter that morning. ‘Spare a thought for the great Tom.’ Then he rode, with a photograph of Tom Simpson taped to the top tube of his bike, as though inspired by his late countryman, fighting almost the entire length – or rather height – of the mountain, from the shelter of the trees as the climb got underway, to the bald, lunar-like upper slopes, where Simpson died during the 1967 Tour.

As they ascended into the sky Wiggins was trailed off, but he fought back, only to be trailed off again, only to fight back again – a yo-yo effort that is torture at the best of times, purgatory on a climb like Mont Ventoux. Approaching the summit, and riding past the Simpson memorial statue, and past Simpson’s daughter, Joanne, who emptied her lungs to yell ‘GO BRAD!’, Wiggins dangled just off the back of the Contador-Schleck-Armstrong group, his mouth wide open, his face a picture of agony. After such an effort, and although at the start of the day the podium had seemed a possibility, his fourth place in Paris – equalling Robert Millar’s best-ever British performance in the Tour, 25 years previously – could only be seen as a glorious triumph.

Wiggins’ fourth-place finish was a game-changer for Brailsford and for Team Sky (and of course for Wiggins). Cavendish, even with his six stage wins, was all but forgotten. With Wiggins now a bona fide Tour contender, how could he not be in the new British team that was setting out the following season to try and win the Tour? And yet, how could he be, given that he was contracted to Garmin for 2010? ‘I would have to be clinically insane to sell that contract,’ said Vaughters, and he had a century’s tradition on his side. Whereas footballers routinely break contracts, and engineer moves to other clubs, such a thing doesn’t happen in cycling.

Still, the speculation couldn’t be stopped. It was not fuelled by Wiggins, who, when asked, consistently said: ‘I’m contracted to Garmin and that’s the end of it.’

At least, it wasn’t fuelled by Wiggins. Not until today, when Brailsford sits down in the Hotel Cadro Panoramica, the British team’s base for the World Championships in nearby Mendrisio, just a couple of hours after Wiggins has given an interview to Jill Douglas of the BBC. Douglas had asked him about the speculation linking him to Team Sky. And ordinarily he would have said, ‘I’m contracted to Garmin and that’s the end of it.’

But in Mendrisio, following a frustrating ride in the World Time Trial Championship, during which he suffered mechanical problems and tossed away his bike in disgust, Wiggins appears, mid-interview, to disengage the part of his brain that should filter out a remark that he might subsequently come to regret. ‘There’s a bit of a tug-of-war going on over who Bradley Wiggins will ride for at the Tour next year,’ suggests Douglas.

‘Yeah, ffffwwoooo,’ says Wiggins, affecting a half-frown, half-smile. ‘I’ll leave it to the experts. It’s unfortunate, that. I’ve had a good year this year at Garmin, but times have changed. The Tour changed everything for me really. We’ll see what happens.’

‘So,’ says Douglas, ‘the lawyers will decide?’

‘I dunno, I dunno,’ says Wiggins, rubbing his chin, biting his bottom lip, looking about as comfortable as a convict – probably because he knows what he’s about to say – yet also strangely relaxed, perhaps because he thinks that what he’s about to say will be liberating.

‘It’s a bit like trying to win the Champions League,’ he tells Douglas. ‘And to win the Champions League, you go to Manchester United. And I’m probably playing at Wigan at the moment. I’ll probably have to make that step to do it.’ (Amusingly, the next day, Wigan beat the champions-elect Chelsea.)

As Brailsford sits down, he smiles and says: ‘No questions on whether we are Man United or Wigan please.’

Now, as the season draws to a close, the British professional team – Team Sky – has never seemed more concrete. Brailsford has been working closely with the team’s first appointed directeur sportif, Scott Sunderland. Actually, Sunderland will be known as a sports director, not a directeur sportif. It is a British team, after all. Sunderland, an Australian ex-rider and previously a director with the Saxo Bank team, has been instrumental in the recruitment process, as he was, briefly, with the Cervelo TestTeam at the end of 2008, leaving to take up the position with Team Sky before a pedal had been turned in competition.

As we sit down with Brailsford in Lugano, Team Sky’s first signings have already been named. Brailsford, though, wants to talk buses. ‘Twelve months ago,’ he says, ‘driving down the motorways of Britain, I wouldn’t have been able to name you a single [make of] coach. But I guarantee you I could tell you now what they’re like, where they’re from, who made them – everything.’

He is talking about the new team bus. But as Brailsford explains the thinking that has gone into it, he offers an insight into the detail he is prepared to go into … ‘Where do you go to get a coach fitted out?’ asks Brailsford. He doesn’t wait for an answer. ‘80% of teams go to two places. We went to those two places and decided it wasn’t what we want. We don’t want a Belgian bus with little tweaks. We’re getting them done by JS Fraser: they make nice buses. But we looked at what they did and thought …’ Brailsford sighs. ‘It wasn’t right. So we got everyone in the next day and looked at it again. We got all our sports scientists, our boffins in, and said: “Right, it’s a box on four wheels, how do you get a competitive advantage out of that space, pre-race and post-race? How do you make sure our guys are better recovered by the time they get to the hotel than any other team? What are you going to put in there – that’s legal?”

‘We’re spending that much money on it,’ adds Brailsford, ‘that it can’t be just a billboard – it’s got to give us an advantage.’

But if Brailsford is going to this much trouble with the team bus, what does that tell us about his approach to everything else? ‘My attitude to the bus is the same as anything else,’ he says. ‘Where you realise you don’t have expertise, you get an expert. So I hired the chief truckie at Honda [Formula One racing team], Gwilym Evans. He’s worked in F1 since 1984, starting with Benetton. Anything that didn’t walk out of the Honda warehouse was his responsibility – every vehicle. And he’s brought new ideas – new for cycling, anyway. He went to a services des courses [where bikes and equipment are stored between races and worked on by mechanics] and the first thing he said was: “Lads, paint the floor white.” The mechanics are saying, “You can’t do that, it’ll get dirty.” But Gwilym says, “That’s the point! We’re going to have a clinical environment.”

‘With the buses, we brainstormed it and figured out what matters. One of the big things is personal space. Ask the riders: they want personal space. They get in the bus in the morning, they’re in the public eye straight away, and they’re in the public eye all day riding their bike. When they come back, they want personal space. So we wanted to optimise that. On the Tour de France, you’ve got nine guys. So there are only nine seats.

‘But we’ve got serious technology on there, too. Where the toilet normally goes, we’ve got a bloody big computer server there. And everyone will have a MacBook Pro console …’

While the image of Brailsford on the motorway, casting his beady eye over passing buses, may be amusing, it seems to be typical of his approach. Nothing is too small or apparently inconsequential to escape his attention, or his quest for ‘marginal gains’. A colleague, Ned Boulting, told me of accompanying Brailsford to Quarrata, the Tuscan base of the British Cycling Academy. Brailsford was inspecting a property that had been acquired to turn into an all-purpose, all-singing, all-dancing, Quarrata base for Team Sky, with services des courses, treatment rooms and accommodation. It included a self-catering apartment. ‘And Dave was trying to work out the optimum layout for kitchen furniture,’ says Boulting. ‘He then spent a good half an hour discussing with Max Sciandri the importance of getting the access road re-surfaced. It was astonishing that he could spend so long on such a seemingly insignificant thing. But it was all about making life as easy as possible for the rider.’

There’s a problem, though. And it has nothing to do with buses, or the layout of kitchen furniture. It has to do with who will lead Team Sky. It is two weeks since the first names were announced. Geraint Thomas, Ian Stannard, Peter Kennaugh – all products of the British Academy – Steve Cummings and Chris Froome are the first British riders named. And there is excitement around some of the overseas riders named – in particular, the Norwegian Edvald Boasson Hagen, one of the most exciting young talents in the sport.

Missing, however, is the British star. There is no Cavendish, no Wiggins. Brailsford has given up on Cavendish – Bob Stapleton is wealthy enough and certainly determined enough not to budge in his commitment to keep Cavendish for the remaining two years of the contract he signed in July 2008. But Wiggins is a different case. He could still be available at a price, though the one recently mentioned by Vaughters seems calculated to deter, or to increase the offer. ‘You’re risking your title sponsorship if you lose your best GC rider,’ said Vaughters. Pressed to put a value on Wiggins, he added: ‘Really, you look at the real value, it is probably in line with $15m.’ That’s a lot of Swiss chocolate.

As he sits down to sign those contracts in Lugano, Brailsford seems unconcerned. He is optimistic and ebullient. ‘There are going to be teething problems,’ he does concede. ‘If it was NASA there’d be teething problems.

‘My tendency in a new project is to get involved, to be very hands on, so I have to pull back – and go and speak to Steve Peters,’ he continues. ‘I want the people involved, the riders and the staff, to feel that they own a part of this, that it’s their adventure; that everyone is there to contribute to the performances of others, so everyone has to feel ownership.

‘It’s the same as the model at British Cycling. We – the coaching and support staff – are the minions. We’re there to help the riders. It’s all about the riders. They’re the kings and queens of their world.’