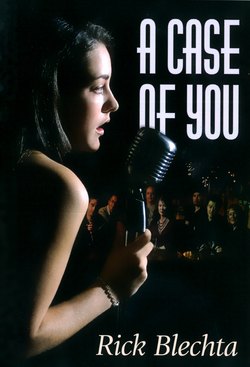

Читать книгу A Case of You - Rick Blechta - Страница 6

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеI had to cast my mind back four months to our steady gig at The Green Salamander Jazz Nightclub – to give its somewhat ponderous full name. The Sal (as it’s better known) has been a mainstay on the Toronto jazz scene for over four decades. Located in a basement space on Toronto’s King Street West near Portland, it is neither plush nor very spacious. Because of this, it has seldom hosted the really big names, unless it caught them on the way up – or down.

As I set up my drums that frigid Tuesday evening in the first week of December, I could see the end of the line approaching fast, an end to the steady gig we’d had for the past two years. Ronald Xavier Felton, our trio’s pianist, refused to acknowledge anything of the kind, but then he was like that. His reality was different from a normal person’s. Dom Milano, our bass player, always went with the flow – and the best payday. As long as the Sal paid, he’d play. When it didn’t, he’d move on – with or without us. He wasn’t mean-spirited, just practical. Jobbing musicians have to be like that.

I cursed under my breath. There were just about no other steady gigs in T.O. these days. Jazz was going through one of its dry periods. Two clubs had closed in the past year. Except for a few annual festivals, a handful of clubs that didn’t offer more than three-night gigs and the odd Sunday Jazz Brunch at a few restaurants, my hometown seemed to have firmly turned its back once again on the music I love.

It wasn’t as if we hadn’t had a good run at the Sal.You couldn’t sneeze at knowing where you were going to be every Tuesday through Thursday for two years. With weekend run-outs, weddings, trade shows, corporate receptions and the like, my finances had never looked rosier.

I’d been able to keep Sandra out of my hair about child support and had gotten to see a good deal of my daughter Kate. That had certainly made the aftershocks of the breakdown of my marriage much less severe on everyone involved than they might have been if I’d been on the road all the time.

Harry, the club’s owner, had begun dropping hints that if business didn’t pick up in a big way, he was going to be forced to shut the doors. Considering he was in his late seventies, that made sense, but he’d also been quoted as saying that the only way he’d ever give up his club was to be taken out feet first.

Weekends were still reasonably good, since he could book touring soloists to be backed up by all-star local pick-up groups, but it was our weekday nights that were killing him, and that meant the Ronald Felton Trio wasn’t pulling its weight.

What had been our Ronald’s brilliant solution? An open mike night. He also wanted to bring in promising local student soloists from programs like the one at Humber College, where he taught two days a week. He’d gleefully told Dom and me that we wouldn’t have to pay them, and they’d fill the place with all their friends.

Dom, his string bass swathed in its padded soft case, the fabric reminding me of a green quilted diaper, stepped onto the low bandstand and gently laid his baby down.

“Think this is going to work, Andy?” he asked.

“An open mike night for vocalists?” I yanked the strap on my trap case, pulling it tight, and shoved it behind the curtain at the back. “It’s only a step above karaoke, for Christ’s sake.”

“Should be good for a laugh, though.”

“The laugh is that Ronald is convinced this will work.”

Dom looked up with a grin splitting his face. “We both know he’s delusional.”

And so it began. That first night didn’t have too many disasters, mainly because our “delusional” pianist had salted the audience with a few capable friends, along with some of his Humber students who also sang.

The weeks went on, and as winter slowly began inching its way to spring, word spread – helped along nicely by a piece in the Toronto Star. More hopefuls than I would have imagined stepped onto the bandstand to strut their stuff. And surprisingly, more regular patrons began coming, too. I figured it was to witness the frequent train wrecks. Disasters always seem to draw a crowd.

The youthful soloists idea also worked pretty well, so I kept my mouth firmly shut. Harry began talking about wanting to be stuffed and laid out behind the bar when he eventually cashed in his chips.

Then Olivia walked in.

Outside, a February storm was blowing, hopefully one of the last gasps of a miserable three-month stretch of extreme cold and snow, but the Sal was still gratifyingly half filled.

Stepping through the door of the club, she looked like a street person. While I prefer to play with my eyes closed most of the time, floating with the groove I’m laying down, for some reason my eyes were immediately drawn to her.

Her brown hair was long, but badly cut, and her baggy clothes, toque and duffel coat looked as if they were straight out of a Salvation Army bin – which turned out to be the literal truth. The only spot of colour was a bright red scarf.

She wasn’t much over five feet, and soaking wet she would have weighed in at not much over a hundred pounds, but there was something about her. She was pretty in a conventional sense – nice lips, cute nose, sort of a heart-shaped face – but her dark eyes gazed right into my soul for a brief moment before she looked away.

I watched her find a perch on one of the tall stools lining the wall in a back corner, places set out for those who wander in alone to catch a set or two. She spent the evening nursing two soft drinks that she paid for from a fistful of small change.

Loraine, the waitress, gave Olivia dirty looks as the level of her drinks got very slowly lower. Tuesdays were generally not good nights for tips, and a couple of colas over the course of an entire evening would hardly pay the rent.

I don’t think anyone but me noticed the waif-like woman as she listened to us accompany hopefuls and drunks with equal equanimity, and even I didn’t catch Olivia as she slipped off her stool and out the door at the end of the evening.

That would never happen again.

I next came across her in a totally unexpected place on a Saturday afternoon a week or so later.

My elderly car was again in the shop, this time for a new transmission. Since I had missed visiting my daughter Kate the previous weekend because of an out-of-town gig, I’d decided to catch the train out to Oakville, where my ex-wife Sandra was living with her new guy in his three-thousand-plus-square-foot house.

Knowing that yet again that bastard Jeremy would look down his long nose at me, my mind was on other things, so I nearly knocked Olivia down as she panhandled for change in between the subway exit and the lower level entrance to Union Station. The Tim Hortons coffee cup in her hand went flying, the coins tinkling as they bounced all over the concrete. Immediately, two other street people appeared from nowhere, stooped and began snatching them up.

“Oh, damn! I’m sorry!” I said.

The poor girl looked as if she might start crying. It took me a moment to realize who she was. She just stared at me, then stooped to pick up her cup and two nickels and a dime that had fallen nearby.

Turning around, I saw the two interlopers scurrying off with their booty. No honour among thieves.

I pulled a handful of coins out of my pocket and dumped them in her cup. “It’s the least I can do.”

Big eyes looked at me, and a shy smile lit up her face. “Thanks.”

Feeling embarrassed, I hurried off with a muttered,“Well, take care,” and went in search of my train.

The whole way out to Oakville, I couldn’t get her out of my mind.

She puzzled me. Had the girl wandered into the Sal simply to get warm? It had been a frighteningly cold night, but you didn’t often see street people in a jazz club – unless they were on the stage playing...

My daughter kept me busy all afternoon, first at a movie then at one of those indoor putting places. The cab fare to and from the big complex out on Winston Churchill Drive where both were located, along with the cost of lunch, movie and putting set me back more than what I made in one night at the Sal, but it was worth it. I’d missed Kate dreadfully since Sandra had taken up with Jeremy, and we’d had a great afternoon.

Eleven-year-old Kate had begun to remind me of my own mother, all dark, curly hair and a broad, pleasant face. She’d never be a beauty like own mom, but her sense of humour and fierce creativity would stand her in good stead. I’d gotten her interested in music, and she showed some talent on the piano. Sandra pushed her hard in school because Kate was very bright. I had no idea how she’d turn out, but I knew she’d be very good at everything she took up.

Whenever I saw Kate, I tried to show her the best time possible. I’m sure a lot of divorced dads do the same. You have to. Jeremy probably made more in three months than I made in a whole year and could give her just about anything.

There was no question that Kate should live with Sandra. With the hours I kept, it couldn’t be any other way – certainly not at her age. Perhaps later that might change, but for now, we had to be satisfied with what felt like stolen moments. Unless I went out of town for a gig, I tried my level best to see her every weekend. We’d share email during the week and talk on the phone. Kate was also after me to get a game system like the one Jeremy had given her so we could both play online. I’d reluctantly promised that I’d get one, not because I wanted to, but because I wasn’t about to let the interloper have one more thing that my daughter could share with him and not with me.

So that Sunday it was a bad movie (we agreed on that), pizza and a game of mini-putt, where we both cheated as much as possible. We also laughed a lot, and I forgot for minutes at a time how hollow the whole thing felt. Kate was just as aware as I how we had to fit a whole week of being together into a few short hours.

On the cab ride back to Jeremy’s, she cuddled up to me and whispered in my ear how she thought he was a “dork”. I squeezed her tight and didn’t say a word, mainly because her words hit me so hard. That was the first time she’d said anything on the subject.

“I love you, honey,” I managed to say as we pulled up in front of her new home.

“And I love you too, Daddy.You take care of yourself this week.You’re beginning to look pretty skinny!”

She kissed my cheek, and I kissed her forehead. Then she ran for the house without another word. Sandra was at the door to let Kate in, and her expression, as she closed it, was as devoid of emotion as ever.

On the train ride back into the city, I worked on my electronic agenda, lining up all the gigs the trio had over the next three months.

Just before the axe had fallen on our marriage, Sandra, Kate and I had discussed going to Disney World. That afternoon, I decided that if I could talk Sandra into allowing it, I’d take Kate there for a week in April. The plane tickets would cost a fortune, let alone rooms, food and Disney World admission, but gigs had been plentiful in the six months since Sandra had split, and I could just afford the trip.

I’d be damned if I was going to let Jeremy get there first with my daughter.

Back at Union Station, the mysterious girl I’d seen at the Sal was still standing outside the subway entrance with her pathetic coffee cup. Snow had begun falling, and that short stretch between the two stations was alive with flakes, dancing as they descended out of the darkness into the light. Even though completely fed up with winter at this point, the sight caught my attention.

It had apparently caught the girl’s, too, because she was standing there, head upturned, watching the big flakes descend. From the amazed expression on her face, you’d think she’d never seen snow before.

Noticing that her attention was elsewhere, a punk made a snatch for her cup.

Reaching out, I grabbed his wrist. Although I’m not the bulkiest guy around, drumming has made my forearms pretty strong, and he couldn’t shake me off.

“Hey, man! Leggo! What do you think you’re doing?”

I leaned forward and said quietly, “Why don’t you just hand the girl back her cup?”

“Man, you’re some kind of psycho!” the little rat said, rubbing his wrist after he’d done what I’d asked.

“Get lost!”

He did, and when I turned to look at her, the girl was staring back with those deep eyes. “You’re the man who was here this afternoon.”

“Yes, I was.”

“That’s twice you’ve done something nice for me. Thank you.”

“My name’s Andy. What’s yours?”

“Ummm...Olivia.”

“Are you always out here, Olivia?”

“Most days. People in Toronto aren’t as generous as they like to make out they are.”

I laughed. “Don’t I know it.”

She laughed, too, a nice sound, then her expression changed. “I have to go now.”

Without another word, she turned and hurried away. What had I done to spook her?

The episodes with Olivia at Union Station fell out of my mind over the next week. The car wound up costing a lot more than I’d been led to believe, and when I began seriously looking into taking Kate to Disney World, the cost of that little excursion was absolutely staggering.

I knew what Sandra would have told me. “Sell the damn house. You know you need the money.”

Fortunately for me, it was my house – completely. When my parents had both died within a year of each other, it had been left to me as the only child, and by a stroke of good fortune, I had inherited their estate three weeks before my marriage to Sandra.

But she was right; I could get a good price for it in Toronto’s superheated real estate market. Houses like mine in Riverdale often went for upwards of a million bucks, a stunning figure, considering what my dad had paid for it nearly forty years earlier. With that money (pure profit), I could buy a condo and put the rest in a retirement plan. I’d be set for my golden years, right?

But I just couldn’t bear the thought of giving it up. It had a soundproof basement studio where I gave lessons to a few students and where I could also rehearse a pretty decent-sized band if I wanted, but it was more than those obvious needs. The place had become part of my psyche, and in my present circumstances, that was a very important thing. Except for a few months at various times over the years, I’d never lived anywhere else.

With a ton of things weighing on my mind, I headed off to the Sal that fateful Tuesday evening, not even really thinking about the gig, let alone a girl I’d only seen three times and had barely spoken to.

Of course, it was raining. It’s always raining or snowing or doing something miserable when I have to move my drums. With a steady gig, I could leave them in place for a few nights, but once we finished on Thursday night, I had to horse them out again. That’s the lot of a gigging musician, something you put up with, but it can be a drag – especially if you’re a drummer. There are a number of parts to a drum set.

Pulling to the curb in a no-parking zone, I put the blinkers on and opened up the hatchback on my old Honda. Take out the trap case, lay the bass drum on top of it, close the trunk and head for the door to the club. Once inside, take the bass drum off the trap case and take each down the steep stairs. By the time I went back to the car to retrieve the two tom-toms, the rain was really coming down.

Normally I would have parked my heap at the lot down the street and carried the two toms back with me, but I decided to take them in first so I could run from the lot to the club more easily.

I had just stuck my key into the hatchback’s lock when a cab swerved to avoid God knows what. It went right down the centre of a puddle next to the car, totally drenching the left leg of my pants.

Cursing, I stared laser beams at the rapidly disappearing cab. A flash of red in a doorway across King Street caught my eye.

It was her – the girl I’d seen at the Sal and Union Station. A streetlight thirty feet away illuminated her face and that red scarf only for a moment before she stepped back, disappearing into the shadows.

If she was here again to listen to the music, why was she waiting outside on such a miserable night?

I thought about going across to say something, but looking down at the sodden condition of my pant leg, I decided against it.

Reaching into the car, I grabbed the two tom cases and took my second load into the club. When I came out again, the doorway opposite was empty.

Ronald was in fine form that night, mainly because a couple of local pianists were in the house. He felt that interlopers (as he referred to them) were always after his gigs. So we defended our turf with a couple of fast opening numbers courtesy of Duke Ellington’s fertile imagination. That got the evening’s festivities off to a good start.

The way the open mike thing had evolved was that interested singers would speak with Ronald before each set. When he found out what they wanted to perform, he’d arrange the song choices in such a way that we didn’t wind up with five ballads in a row, or two people singing the same tune back to back.

The first sets each week were generally the best for two reasons: the people who had come specifically to sing most often wanted to sing early. The third set featured more of the sort of performances that relied on “Dutch courage”, the half-drunken person saying, “I can sing better than that clown!” followed by his or her equally drunk acquaintances goading the poor soul on. Those were our “train wrecks” – frightening, pathetic and comical all at the same time.

The girl must have slid in sometime during the first set while my attention was occupied elsewhere. In the second-to-last tune, an older gentleman who’d sung a few times in recent weeks was in the middle of a competent rendition of “Chattanooga Choo-Choo” when I looked over at that dark corner of the club, and there she was. She had on the same worn blue duffel coat and the black toque jammed down on her head. Her face had a small frown of concentration as she mouthed the lyrics with the singer.

I again thought of going over to speak with her but got corralled into a conversation with two of the club regulars. By the time that broke up, we had to start the second set.

As the evening progressed, we had some surprisingly good performances and only a few disasters, none of them too excruciating. Dom, Ronald and I were playing well, and in a few tunes we stretched things out a bit, which left the poor vocalists standing around with nothing to do, but hell, we were feeling good. I forgot about the waif at the back of the club.

We were getting ready to finish off the final set with a couple of nonvocal numbers when the girl appeared next to Ronald’s grand piano, staring at us with huge, frightened eyes.

“What is it?” he asked testily. “Do you have a request?”

The girl shook her head. “I want to sing,” she said in a tiny voice. “The open mike night is over. If you want to sing, you’ll have to come back next week.”

She didn’t move. Even with the duffel coat on, it was easy to see she was absolutely quaking in her boots. Coming up to the bandstand had taken a lot of courage on her part.

“I want to sing,” she said softly but defiantly.

Dom, perhaps sensing that this might be a good bit of sport, said, “Aw, let her, Ronny,” then turned to the girl. “What song, darling?”

She mumbled something indistinguishable.

Ronald decided to remain obnoxious – not much of a stretch for him. “If that’s how loud you sing, you’re not going to make much of an impression on the audience.”

As he stretched out his hand to indicate the sixty or so people still in the club, the poor girl’s eyes got wider, and I felt certain she’d bolt. I suddenly remembered she’d told me her name.

“Olivia,” I said loudly to attract her attention, “tell us the song you’d like to sing.”

She looked at me gratefully. “‘Skylark’. Do you know ‘Skylark’?”

Ronald rolled his eyes, since a woman had already sung it in the previous set.

“What key do you sing in?” Ronald asked impatiently.

Olivia looked confused. “I don’t know.”

“Then how can we play it?”

Her eyes pleaded with me for help.

“Can you sing it in the same key that we played it in earlier?” I asked.

“I guess so.”

Dom nodded. “B flat then, Ronald. The lady wants to sing.”

With her coat, hat and that scarf still on, she stepped onto the bandstand with a look of resolution. It took her a moment to figure out how to drop the mike stand to her height, but finally she looked over at Ronald, and with tight lips, nodded.

One of the two visiting pianists was still in the house, half-potted, having an earnest conversation with one of the better female vocalists of the evening, so Ronald made up a totally different intro to the song than the one he’d used earlier, and it really was quite brilliant. Olivia, totally at sea, turned to me with a frightened look, so I smiled and nodded reassuringly, indicating I’d help her come in.

Ronald finished with an arpeggiated chord roll to the upper end of the piano, and I mouthed “two, three, four” to bring her in.

She turned to the audience, shut her eyes and started to sing. “Skylark, have you anything to say to me...”

I had my brushes out, planning to join in for the second verse, and damn near forgot to come in.

The performance of this very odd girl was, to put it mildly, stunning.

There are always people who insist on talking through every song, regardless of the fact that it’s rude, irritating and distracting to those people who want to listen, but especially so to the musicians. By the time Olivia was halfway through the first verse, every eye in the house had turned to the stage. Even the bigmouth at the bar stopped gassing.

It wasn’t so much her voice – although no one could possibly have any complaints in that department. What had every person in that club riveted was Olivia’s delivery. The girl could flat out sell a song like nobody I’d ever heard.

“Skylark” is not a song you can belt out. It must be subtle, wistful, delicate, ingenuous. It’s about a young girl asking where her first love might be found. The performance earlier in the evening, which had been quite good, paled to black and white in comparison to the way Olivia was singing.

We always set up with me facing Ronald and Dom in the middle, since he’s the glue that holds us together musically, so I had a good view of her. Her eyes were shut tight, and she gripped the mike stand with both hands as if it were saving her from drowning, but her body remained supple, swaying gently with the music. Her awkward-looking outerwear suddenly didn’t seem important as the subtle nuance of her melodic shadings washed over us. You could visualize her having run in off the street to tell everyone about her search for love. I felt as if I were hearing this song for the very first time.

The trio rose to the occasion, giving this girl the very best we could – even Ronald. He’ll occasionally get overly busy, especially if he’s bored or put out. His playing in this song was easily the best he’d done in some months, matching Olivia’s understated performance with one of his own. He only took a two-chorus solo before he led her in for the last verse with a gentle nod, and smiled broadly as he ended the song with a gentle whisper of melody high up the keyboard.

For a moment there was silence before everyone remembered to breathe. Then the place just went nuts.

Olivia stood there for a moment with an increasingly fearful expression on her face, then turned, and with everyone cheering, she ran right out of the club as if the devil were at her heels.

“Interesting way to end a performance,” Dom observed as he leaned on his bass. “Damn good vocalist, though.”

Olivia’s singing haunted me the rest of the week. I wished someone had taped it.

The following week, she didn’t show up on Tuesday, and I was sure the girl had either got it all out of her system, or had completely freaked herself out. More than one regular asked if “that interesting singer” was coming back. Even Harry inquired if we were going to hire her.

Wednesday noon found me downtown to get my passport renewed, so I took a walk over to Union Station, to see if she was there. Street people are creatures of habit, staking their turf and guarding it jealously.

No sign of her, so I grabbed lunch in one of the fast food joints in the underground city, that maze of interconnected office buildings stretching from the train station all the way up to Dundas Street.

Back at Union for a last try, I got no glory, but some old guy was hawking one of those street newspapers homeless people sell. I’d seen him there the previous time I’d encountered Olivia.

“I’m looking for a girl—”

“Isn’t everyone?” he interrupted with a broken-toothed grin.

If he was looking to sell a paper, bad comedy wasn’t going to get him there.

“This is a particular girl,” I said patiently, “maybe five-foot-two, pretty, big eyes, long dark hair, wears a navy duffel coat and a black toque. Not your average street person. Know who I’m talking about?”

The guy looked purposefully down at the sheaf of papers under his arm. I got the message and forked over a tooney, twice what the paper was worth.

“She’s here most days. The cops did a sweep of the area, and she skedaddled like all the other panhandlers. Odd one, though. She spooks kind of easy.”

“When is she usually around?”

“You ain’t a cop, are you?”

“Do I look like a cop?”

He cocked an eyebrow at my stupid question.

“No,” I sighed, “I’m not a cop. She’s just someone I met.”

His grin told me he’d imagined a meeting far different from the reality.

“If she shows, it might be around three, maybe three thirty. The evening rush is usually pretty good.”

After that, I felt I’d committed myself to sticking around.

From up above at street level, you can see the open area where Olivia had her spot. In order not to spook her again, I hung out up there, occasionally checking to see if she’d arrived. Luckily, the February weather was a little more moderate that day than it had been, because I had to wait until nearly four o’clock before the black cap and red scarf were directly below me. Her outstretched Tim Hortons cup with two quarters in it jingled loudly when she shook it.

Okay, I’ll admit it. I snuck up on her. It wasn’t hard, since most of the traffic at that time is headed into the station. I forced my way upstream and came at Olivia from her blind side. When I gently touched her shoulder, she flinched as if I’d struck her.

“Hello, Olivia,” I said, smiling to look friendly and harmless.

“What are you doing here?”

“I just wanted to say how much I enjoyed your singing last week. We were all hoping you’d show up last night and sing some more.”

“That was a stupid thing for me to do!”

“Why? You were really good.”

“That’s not what I meant. Now leave me alone.”

When I didn’t immediately disappear, she demanded again, “Leave!”

I smiled. “Let me buy you a cup of coffee. You’re shivering.”

“No. I’m busy.”

“How about a coffee and a ten dollar bill, then? In the time it takes to have a coffee, you won’t make that standing here.”

The dirty white running shoes she had on looked pretty soaked. I think cold feet swung the deal.

“Okay,” she finally said. “Where?”

“How about just inside the station? That way you won’t have far to go when we’re finished.”

I bought her a large double-double and a toasted bagel. We went over to the seats where you wait for the local trains.

Olivia wolfed down the bagel. While she chewed and sipped her coffee, I waited patiently, trying to figure her out.

Toronto has a lot of street people. It’s part of our city’s shame. But something about this girl didn’t seem quite right.

I put her age at well over twenty, far too old to be a runaway. She also didn’t have that spaced out look of the alcoholic or druggie. With her torn jeans and ratty coat, her appearance wasn’t the best, that was for sure, but her hair wasn’t dirty, and she didn’t smell. She knew I was studying her but kept her eyes averted.

As the last bit of bagel disappeared, she licked a dab of cream cheese off her finger, and I spoke. “You sing really well, you know.”

Her head stayed steadfastly down. “I do?”

“Couldn’t you tell by the way the audience reacted?”

She shook her head and gave me a sidelong glance. “I shouldn’t have done it.”

“Why?”

“Can’t tell you.”

I took another tack. “If you ever came back again, what song would you want to sing?”

She took a long time to answer. The flow of people around us had increased as the downtown office towers emptied for the day. If she’d wanted to bolt, there would have been little I could have done to stop her, and she had to know that.

“Cole Porter. I like Cole Porter.”

“What song?”

“‘Just One of Those Things’.”

“You like that one?”

She nodded. “I used to sing it for my daddy.”

“You know, if you wanted, you could come down to the club, tonight even, and sing with us. We might be able to offer you a job. You wouldn’t have to hang out here any more.”

She took that in. “I don’t think so.”

“Don’t worry about being frightened to sing in public.You’d soon get used to that.”

“I shouldn’t do it.”

“Why not? A steady paycheque has to be better than panhandling. Safer, too.”

Her eyes suddenly got big again, but she said nothing.

Patting her shoulder, I said, “Come down tonight and sing a couple of Cole Porter tunes with us. Okay?”

I knew I should leave or risk having her run away again, and I also knew next time I wouldn’t find her so easily.

As I walked towards the subway, she remained behind, but I could feel her eyes on my back.

Since it was the second night of our three-day gig, I didn’t have to set up my drums, but I arrived early to check out the doorways in the area of the Sal. No sign of Olivia.

By the time the first set had ended, I’d convinced myself she wouldn’t show. I couldn’t have told anyone why it was so important, but I just knew that it was. After all, the girl had only sung one ballad with us.

She had good rhythm and listened to what was going on around her, that was clear. Even Ronald couldn’t fault her pitch. I felt confident that whatever makes a great vocalist, she had it in spades.

As we sat down at our usual table, I casually mentioned to Dom and Ronald that I’d seen Olivia and invited her to sit in again. The bass player greeted that news enthusiastically, the pianist phlegmatically. I wondered what his problem was.

She slid in between the second and third sets, and I immediately saw her standing uncertainly by the door. Getting to my feet, I motioned her over to our table. This time, though, she wasn’t alone. A woman, definitely older and with less of an air of indecision, followed in her wake.

“I’m glad you made it,” I said as I helped her off with her coat.

She had on a reasonably nice black dress. From the way it fit her, it had probably been borrowed or picked up at the Salvation Army Thrift Store or some such place. Still, it looked reasonable, if a bit old-fashioned. Around her neck was another scarf, this time a white silk one that complemented the dress nicely.

Dom slid over two seats to make room for the newcomers. Olivia just about fell into her chair, and I could see she was even more nervous than the week before.

The friend said nothing, and Olivia didn’t make an effort to introduce her. She looked to be at least fifteen years older than Olivia and definitely more careworn. Her face had a wary expression, and I got the feeling she’d been dragged down to the Sal against her will, or that Olivia had come against her wishes. She said her name was Maggie, but something told me it also might not be.

Dom leaned over towards the frightened girl and said in his usual friendly manner, “Andy told us you’d like to sit in.”

She kept her head down. “He asked me to come.”

“So what will you be singing?”

“‘Just One of Those Things’,” I answered for her. “Maybe another Cole Porter tune or two.”

“Like what?” Ronald asked sharply.

“I know ‘I’ve Got You Under My Skin’,” she answered.

“And I suppose you don’t know what key you want to sing them in.”

I was about to tell Ronald to back off, but Dom saved me the trouble. “Just sing them, honey, and I’ll tell you what key they’re in. Okay?”

In a very soft voice, Olivia started ‘Just One of Those Things’ and Dom immediately said, “That’s in A.”

Her other chosen tune was in G. We were ready to go.

As the other two got ready, I pulled the vocal mike and stand to the centre of the bandstand and turned it on, checking its level.

Ronald insisted on opening the set with a rather Bill Evans-like rendition of the Porter tune “Night and Day”, and it went on far too long. I kept my eye on Olivia, but my attention wandered when I did a brief solo at the end of the song. When I opened my eyes, I noticed that both women were missing.

Cursing Ronald under my breath for not starting the set with Olivia’s songs, I was about to let him have it when they appeared from the corridor leading to the washrooms. Maggie looked even less happy than before, but Olivia had a very determined glint in her eye as she led the way.

Ronald switched on his mike, announcing to the club that we had a special guest who’d dropped by to sing a few songs. Olivia, having sat down again at our table, popped up immediately and stood there. Dom motioned her towards the bandstand, and she came much more readily than she had the previous time.

“Will somebody help me come in?” she asked shyly.

“Sure thing, sugar,” Dom said.

Olivia seemed a bit more relaxed (as evidenced by her actually letting go of the mike stand a few times), and her performance was that much better because of it. Often she’d sink so far into the songs that she actually seemed to become the person described by the lyrics. The effect was quite astonishing and had the patrons of the club mesmerized – not to mention her backup band. The girl could swing, she could shout, she could be tender. I could only imagine what Olivia would be like with a little rehearsing under her belt.

She wound up doing the rest of the set with us. We would suggest songs until we came up with one she thought she could do, she’d sing a few bars so Dom and Ronald could get the key, and we’d be off.

By the end of the set, she had everyone in the palm of her ingenuous hand. That performance was the stuff legends are made of, and I’ve heard at least three times the number of people who were actually present that night say they were there.

The only person who looked unhappy was Olivia’s friend. As we came off the stand, Dom put his arm around Olivia. “Would you like to sing with us steadily, sugar?”

I thought for a moment that Ronald would object, but he finally nodded in agreement.

I watched her carefully until she said, “I don’t know...”

“Why don’t you come back tomorrow night and sing some more? You don’t have to make up your mind on the spot. Right, gentlemen?” he said, looking more at Ronald than me.

She smiled happily at that, although her friend looked (if possible) even more put out.

“So you’ll come back?”

“Maybe,” was all she answered as she hurriedly put on her coat. People tried to talk to Olivia as she made her way to the door, but her friend urged her on. They disappeared into the night as quickly as they’d arrived.

It was the first of many nights for the four of us at the Sal.