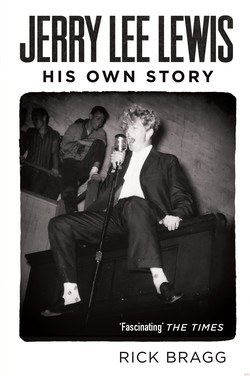

Читать книгу Jerry Lee Lewis - Rick Bragg - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

JOLSON IN THE RIVER

The Black River, and the Mississippi

1945

The party boats churned up the big river from New Orleans and down from Memphis and Vicksburg, awash in good liquor and listing with revelers who dined and drank and danced to tied-down pianos and whole brass bands, as their captains skirted Concordia Parish on the way to someplace brighter. The passengers were well-off people, mostly, the officer class home from Europe and the Pacific and tourists from the Peabody, Roosevelt, and Monteleone, clinking glasses with planters and oil men who had always found riches in the dirt the poorer men could not see. Weary of the austerity of war, of rationing and victory gardens, of coastal blackouts and U-boats that hung like sharks at the river mouth, they wanted to raise a racket, spend some money, and light up the river and the entire dull, sleeping land. They floated drunk and singing past sandbars where gentlemen of Natchez once settled affairs of honor with smoothbore pistols and good claret, and around snags and whirlpools where river pirates had lured travelers to their doom.

The country people, in worn-through overalls and faded flour-sack dresses, watched from the banks of the Mississippi and Black rivers the same way they looked through the windows of a store. In the war years, they had traded the lives of their young men for better times, but they had seen too much bad luck and broke-down history to overcome with just one big war. Reconstruction, the Great Depression, and named storms and unnamed floods had left generations hunched over another man’s cotton, and in their faces you could read the one true thing: that sometimes all you could get of a good life was what you could see floating just out of reach, till it disappeared around a bend in the river or vanished behind a veil of flood-ravaged trees. And sometimes, hauntingly, even when a boat had passed them by, they could still hear the music drifting down-river as if there was a song in the water itself, Dixieland or ragtime or, before they turned away to their lives in the colorless mud, a faint, thin scrap of Jolson.

Down among the sheltering palms

Oh, honey, wait for me.

He was still a boy then. One day, when he was nine or ten, he stood on the levee beside his mother and father as one more party boat pushed against the current, well-dressed people laughing on deck. Safe in the middle of the Black River, they raised their glasses in a mocking toast to the family ashore. “They tipped their mint juleps at us, tipped ’em up,” he says, and smiles the faintest bit to prove how little it matters to him after so much time. But it mattered to the man and woman beside him. His daddy was indestructible then, gaunt, six foot four, with big, powerful hands that could squeeze weaker men to their knees, and a face that seemed drawn only in straight lines, like Dick Tracy in the funny papers. As the drunken revelers lifted their glasses of bourbon high in the air, Elmo Kidd Lewis pulled the boy to his hip. “‘Don’t worry, son,’ Daddy told me. ‘That’ll be you on there someday. That’ll be you.’” He does not know if his daddy meant it would be him up there with the rich folks, the high and mighty, or if it would be his songs they played as the boat passed by. “I think maybe,” he says, “it was both.”

Elmo knew it the way he knew wading in the river would get him wet. He had seen it, he and his wife, Mamie, when his son was barely five years old, seen a power take over the boy’s hands and guide them across a piano he had never studied or played before. For the boy, it was . . . well, he did not truly know. His fingers touched the keys and it was like he had grabbed a naked wire, but as it burned through him, it left him not scorched and scarred but cool, calm, certain. Only God did such as that, his mama said, and his daddy bought a piano for the boy, so the miracle could proceed.

Finally, something worth remembering.

He rests now in the cool dark of his bedroom and lets it draw at the old poisons in him like a poultice. He is a swaggering man by nature, but for a moment there is no strut in him.

“Mama and Daddy,” he says, “believed in me.”

He tried to pay them back, with houses and land and Cadillacs. “‘Money makes the mare trot,’ Mama always said.” But the debt will never be settled. The piano, the weight of it, tilted the world. He still has it, that first piano—the wood cracked and buckled, deep grooves worn in its keys—in a dim hallway in a house where gold records and other awards pile like old newspapers or lean against a wall. He pauses before the ruined piano now and then and taps a single key, but what he hears is different from what other people do.

The boat that taunted them is a ghost ship now.

The old songs sank beneath the water.

Elmo’s boy, scoured by a worldly hell and toasted by kings, is still here.

In the summers of 2011 and 2012, I listened in the quiet gloom of his bedroom as he told me what was worth remembering. He told me some of the rest of it, too, when he felt like it, for as long as he felt like it. He remembered it as it pleased him. That does not mean he always remembered it the same way twice, but day after day I was reminded of a line I once read: it was like any life, really, but with the dull parts taken out. It was odd, though, how he could see the boy on that levee so much clearer than he could see all the long life in between, like he was looking across that wide river again, at himself.

Before he rocked them, before the first piano bench went hurtling across the stage and first shock of yellow hair tumbled into his snarling, pretty face and the first spellbound, beautiful girl stared up from the footlights in unmistakable intent, he played Stick McGhee songs for Coca-Cola money from the back of his daddy’s beat-up flatbed Ford and sang Hank Williams before he knew what a heartache was.

Before Memphis, before he took them from the VFW and convention halls to a place they’d not been even in a fever dream, before preachers and Parliament damned him for corrupting the youth of their nations, before he made Elvis cry, he listened to the Grand Ole Opry on his mother’s radio, the battery she saved all week till Saturday night finally fading to nothing at the end of a Roy Acuff song.

Before bedlam, before he stacked money and hit records to the sun and blazed up, up, to come smoking to earth only to rise and fall and rise and rise again, before he outlasted almost all of his kind and proved on ten thousand stages that no amount of self-destruction could smother his voice or quiet the thunder in his left hand, before John Lennon knelt and kissed his feet, he performed his first solo in the Texas Avenue Assembly of God, then hid under a table in Haney’s Big House to see people grind to the gutbucket blues.

Before any of it, before the first needle and first million pills, before the first coffin passed him by, he walked a high bridge rail like a tight-rope between the bluffs of Natchez and the Louisiana side, laughing, loving the scare it threw into mortals below. A lifetime later, he rode across the same bridge and looked down to the muddy water of the Mississippi, to barges long as a football field; from up there, they looked like toys in a bathtub.

“I must’ve been crazy,” says Jerry Lee Lewis, but if he was, it was just the beginning.

The weather seems different now from when he was a boy, the air so hot and thick the sky looks almost white. The afternoon thunderstorms that have shaken this land across generations now hang hostage in that cotton-colored sky, leaving the air wet and steaming but the fields dry as parchment for weeks, a thing the old people attribute to the end of days. But the end of days has been coming here for a long, long time.

“I wonder what it’s like to die? I guess they give you shots and stuff, to help you with the pain. I don’t really know,” he says, softly, as Ida Lupino and Beware, My Lovely roll across a muted television screen. “Probably, you just drift off to another world. I don’t know what that world will be like. I like to think it’s Heaven. Can you imagine me in Heaven? Imagine the orchestra we’d have.” He tosses a macadamia nut in his mouth, unscrews an Oreo, takes a long swig of purple soda, and ponders that. “Oh, man, what a band. I’ll want to go twenty-four hours a day . . . won’t never get tired. Won’t never stop.”

He has never believed the grave is the end of a man, and that has been his torture. The greater part of a man walks in Glory or burns; there is no real in-between, not in the Assembly of God. Across his life, he has proclaimed on a rolling basis the kind of man he considers himself to be, shifting from world-class sinner to penitent, sometimes in the space of a single song. Now his choice seems finally made. I am warned by members of his family, before I even enter his presence, that he abides no cursing, no blasphemy. He will live the rest of his life, he hopes, without offending God. He tithes. He blesses his food and prays at night the Lord his soul to take. He knows the Holy Ghost is as real as a pillar of fire. He believes, as always, in the God of Texas Avenue, and knows he has sinned greatly, deeply. But his God is a God of miracles and redemption, and in this case that might amount to about the same thing.

“I did a lot of thinkin’ about that. . . . Still think about it, real heavy. I sure don’t want to go to Hell. If I had my life to live over, I would change a lot of things,” he says, not for the approval of man, but for the grace of God. “I believe I would. I’d probably not do a lot of things that I’ve done. . . . Jesus says, ‘Be thou perfect even as my Father in Heaven is perfect.’ But my Lord, I’m only human. And humans tend to forget. I don’t want to die and my soul go to Hell.

“There is a Hell,” he says. “The Bible plainly speaks of it, very big-time. The fire never quenches, the worm never dies. The weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth. The lake of fire.”

But he can bear that, he believes, better than the rest of it.

“I just want to meet them, meet all my people that I have ever lost, in the new Jerusalem,” he says. “I often wonder about that. God says you will know as you are known, and if you don’t see them there, it will be as if you never knew them. That’s awful. It worries me,” the notion that if he is cast down, it will be—to his people, even his children—as if he had never lived. “That’s heavy, ain’t it?”

“The answer is written in the book of life, for me,” he says, and the heat in his eyes tells you this is not mere rhetoric but deadly serious. “Can a man play rock-and-roll music and go to Heaven? That’s the question. It’s something that won’t be known . . . that I won’t know, till I pass away. I think so, but it don’t matter what I think. And I will take all the prayer I can get.”

The question almost pulled him apart, as a younger man. Elvis, who would understand the question perhaps better than any other man, was haunted by it, too. Jerry Lee would have liked to talk with him about it, but Elvis hurried away, face white as bone; and then he left this world, leaving Jerry Lee to grow old with it alone.

The thing he has come to believe, to hope, is that whatever happens in this life or beyond, it is not purely the music’s fault. People blamed the music for everything.

“It’s not the devil’s music,” he says, sick and tired as he would be of any pretender, any hanger-on.

He is almost eighty years old now. He knows what he has wrought.

“It’s rock and roll.”

The devil was no troubadour. The theater of it all, the convenient women and bottomless liquor and jet-plane parties, the whipped-out knives and waistband pistols and bags of blues and yellows, might have drawn the devil like green flies, but the devil never called a tune or found a chord, not even in the nastiest blues or most whiskey-soaked cheatin’ songs or any other music that moved a waitress to wiggle her hips or a farm boy to dance in his socks or a notary public to shake the hot rollers out of her head.

“My talent,” he says, “comes from God.”

Mamie tried to tell them, even as she worried where it would all end.

“I can lift the blues off people,” he says.

He did some meanness, God knows he did.

But the music—funny how it turned out—was the purest part.

Mama’s cookin’ chicken fried in bacon grease

“The only piano player in the world . . .” he says.

Come along boys, just down the road a piece

“ . . . to wear out his shoes.”

In the twilight of his life, in the late nights of the here-and-now, he sometimes still wonders: “Did I lead them people down the right way?”

But he did not take the people anywhere they were not ready to go. Even in the most barren times, when cigarette smoke hung like tear gas in mean little honky-tonks and he might have missed a step on his way to the stage, he gave them something they were looking for. People say a lot of things about him—“talk about me like a dog,” he says—but few people can say he did not put on a show. They talk about seeing him and grin and shake their heads like they got caught doing something, like someone saw their car parked outside a no-tell motel in the harsh light of day. They grin and talk about it not like a thing they witnessed but like a thing they lived through, a meteorite or a stampede. It usually started without fanfare; he just walked out there, often when the band was in the middle of a song, and took a seat. “Gimme my money and show me the piano,” he often said of how the experience would begin. But it ended like an M80 in a mailbox, with such a holy mother of a crack and bang that, fifty years later, an old man in a Kiwanis haircut and an American flag lapel pin will turn red to his ears and say only: “Jerry Lee Lewis? I saw him in Jackson. Whooooooooo, boy!”

Joe Fowlkes, a Tennessee lawyer, likes to tell about the time in the mid-1980s when he heard Jerry Lee do four hours at his piano without a break, after he was already supposed to have been dead at least twice. “We all went to see him at the dance hall at 100 Oaks” in Nashville, he recalls. “They called it a dance hall because it was better than calling it a beer joint.” Jerry Lee showed up looking a little worn and pale, and he started off slow—“it was kind of gradual, like watching a jet taking off”—but he played and he played and he played, and it was three o’clock in the morning before he got done. “He kind of got his color back, after a while. By two-thirty in the morning, he was lookin’ good. He played every song I’d ever heard in my life, including ‘Jingle Bells’ and the Easter Bunny song. And it was July.

“It was the best concert I’d ever been to. I saw Elvis. I saw James Brown.” But Jerry Lee. “He was the best.”

“There was rockabilly. There was Elvis. But there was no pure rock and roll before Jerry Lee Lewis kicked in the door,” says Jerry Lee Lewis. Some historians may debate that, but there was no one like him, just the same; even the ones who claimed to be first, who claimed to be progenitors, borrowed it from some ghost who vanished in the haze of a Delta field or behind the fences of a prison farm. People who played with him across the years say he can conjure a thousand songs and play each one seven ways. He can make your hi-heel sneakers shake the floor-boards, or lift you over the rainbow, or kneel with you at the old rugged cross. He can holler “Hold on, I’m comin’” or leave you at the house of blue lights. Or he can just be still, his legend, the legend of rock and roll, already cut into history in sharper letters than the story of his life. Sam Phillips of Sun Records, a man who snagged lightning four or five times, called him “the most talented man I ever worked with, black or white . . . one of the most talented human beings to walk God’s earth.”

“I was perfect,” he says, “at one time. Once, I was pretty well perfect when I hit that stage.” On another man, such a claim would wear like a loud suit. On Jerry Lee Lewis, it sounds almost like understatement. Roland Janes, the great guitar man on so many Sun Records hits, once said that not even Jerry Lee knows how good he is.

He knows. He likes to use the word stylist when referring to some of the musical greats who came before: it is his highest compliment. A stylist is a performer—not necessarily a songwriter, yet still a creator—who can take a thing that has been done before and make it new. “I am a stylist,” he explains. “I can take a song, a song I hear on the radio, and make it my song.” He can remember the first time he felt that power, too. “I was fifteen years old. Back then I played the piano all day and then at night I’d lay in bed and think about what I’d play the next day. And I see records that was out there, see the way they were going, and I just thought that I could beat it. Back then, I was playing the skating rink in Natchez, on this old upright piano—I remember it wasn’t in very good shape—and I played everything. I played Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, boogie-woogie, and I turned it all into something else. What did I turn it into? Why, I made it rock and roll.”

He made it roll and thump in the spaces between the plaintive lyrics, a thing of rhythm impossible to describe in words. “The girls crowded around me and the boys got all upset and wanted to start a fight, but before long ever’body was lovin’ it. I can see ’em now. And it was love. Pure love. I loved it, and they loved it. That don’t come around too often, I don’t believe. And it wadn’t just the song they loved, it was the way.” At first he was struck by the power, at the rapt faces, the heaving chests, but did not marvel at it for long. “If you know you can do a thing,” he says, “then you ain’t never surprised.”

He is not, even with the years tearing at him, a soft man. His body has been hammered by hard living, and scoured by chemicals, and pain-racked by arthritis and most of the ailments of Job, but now he is rallying again, with clean living and that mysterious thing he has always had cloaked around him, something beyond science. He is still a good-looking man, his hair faded from gold to silver; he still records and fills concert halls in the United States and Europe, though he admits it is sometimes all he can do to finish a show. Young women still push to the edge of the stage and try to follow him back to his hotel room. Now it is his prerogative to tell them no, because the shows exhaust him. What a sorry thing, a rotten choice for a good lookin’ rock-and-roll singer to have to make.

“If I’s fifty-one,” he says, “they’d have to hide the women.”

He lives near the river still, south of Memphis in the low, flat green of north Mississippi on a ranch with a piano-shaped swimming pool, behind a gate with a piano on the wrought-iron bars. Here the living history of rock and roll sits unrepentant to any living man, and even as he tells you his life story, he seems to care little what you think. “I ain’t no goody-goody,” he says, the Louisiana bottomland still thick on his tongue, “and I ain’t no phony. I never pretended to be anything, and anything I ever did, I did it wide-open as a case knife. I’ve lived my life to the fullest and I had a good time doin’ it. And I ain’t never wanted to be no teddy bear.”

He has been honored by state legislatures and dog-cussed over clotheslines. He has disowned children and walked away from wives and girlfriends—even in the age of DNA, none has challenged his actions—and does not much care that his life and his choices might not make sense to other people. “I did what I wanted,” he says. He lived in the moment, unconcerned what those moments would add up to in the eyes of men. “Other people,” he says, “just wished they could have done what I done.” He is unconcerned with worldly redemption. He has bigger worries than that.

He has played over seven decades, from pubs to palladiums, from soccer stadiums to Hernando’s Hideaway South of Memphis, for thousands, or hundreds, or less, because even when there was no one to play for but a handful of drunks or hangers-on, there was still the talent, and when you have a jewel, you do not hide it in a sock drawer. Raw and wild in the 1950s, almost forgotten in the mid-’60s, a honky-tonk chart-topper by the early ’70s, and a Rolls-Royce–wrecking, jet plane–buying crazy man in the late ’70s and ’80s, he always played. He absorbed scandal—Rolling Stone virtually accused him of murder—and played when he could barely stand. He spent two decades wandering the wilderness, overmedicated, set upon by the tax man, divorce lawyers, everything but a rain of toads. There were more fights and pills and liquor and car crashes and women and discharge of firearms—accidental and on purpose—than a mortal man could be expected to survive, but he played.

I approached him with great anticipation—and one reservation, as to getting shot. People told me he was mercurial; some said he was crazy. He shot his bass player, they said. Why not shoot a book writer? Instead, across the days, he was mostly gracious, and asked about my mother. “I hit this one guy in the face with the butt of the microphone stand,” he tells me, as he eats a vanilla ice cream float. He actually hit four or five that way. He remains willing to take a swing at a man who offends him and suffer the prospect that some drunk redneck half his age will not care he is living history and knock him slap out. His bedroom door is reinforced with steel bars. I started to ask about that but decided I did not need to. He still has a loaded long-barreled pistol behind a pillow, a small arsenal in a dresser drawer, and a compact black automatic on a bedside table. Holes in a bedroom wall and an armoire prove that all that has come to claim him in the night, ghosts, bad dreams, or time itself, has been dealt with violently. A bowie knife sticks in one door. A dog sleeps between his feet—a Chihuahua, but it bites.

He has, in old age, a stiff-necked and—all things being relative—sober dignity, but do not say he is growing old gracefully, any more than an old wolf will stop gnawing at his foot in a steel trap. It is harder, even now, to explain what he is than what he is not. He is not wistful, except in the rarest moments, and does not act wounded; he just gets mad. He does not swim in regret, even when he walks between the graves of two sons and most of the people he has ever loved. Six marriages ended in ashes, two of them in coffins. He believes he is due some things but not the right to whine. A man like him forfeits that. A Southern man—a real one, not these modern ones who have never been in a fight with a jealous husband or changed a tire or shot a game of pool outside the church basement—does not whine, anyway. “It didn’t bother me none,” or “I didn’t think much about it,” he often says when talking about things that would have torn another man down to his shoes. Then he would physically turn away. In time I came to understand that remembering, if you are him, is like playing catch with broken glass.

His friends and closest kin, most of them, are protective of him now, always polishing his legend. They will fight you if you question his generosity, or the goodness that, they assert, shines just beneath his more public persona. He has played benefit after benefit for charity, even when he himself was busted, or nearly so. That does not mean he does not expect to get his way, almost all the time. “He don’t jump on top of the piano anymore,” said guitar picker Kenny Lovelace, who played three feet away from him for forty-five years. “But still, he walks out there and sits down, and you know the Killer is here.”

“I was born to be on a stage,” says the man himself. “I couldn’t wait to be on it. I dreamed about it. And I’ve been on one all my life. That’s where I’m the happiest. That’s where I’m almost satisfied.” He knows that is what musicians say, what a musician, in his twilight, is supposed to say. “I do really love it,” he says, in a way that warns you not to doubt him. “You have to give up a lot. It’s hard on a family, on your women, on the people that loves you.

“I picked the dream.”

Even if it was worn and scarred, or hidden in some raggedy place at the end of a gravel road, or protected by chicken wire, he would drive six hundred miles, even club a man with a microphone, to possess it. And for much of his life he gave his fans more than they paid for, gave it to them slow and soulful and fast and hard, till the police came clawing through the auditorium doors, refusing to relinquish the stage even as other rock-and-roll idols, including the great Chuck Berry, waited helpless and seething in the wings. In Nashville, three hundred frenzied girls in the National Guard Armory tore his clothes off his body, “down to my drawers,” and he grumbles about it to this day, about all those crazed, adoring women, because they cut short a song, dragged him off the stage, and cut short the show.

The dream is why, when news of his marriage to his thirteen-year-old cousin, Myra, caused promoters and some fans to turn away and his rocket ship to sputter, when scandal and changing times caused record sales to sag, he filled two Cadillacs with musicians and equipment and went on the road. He played big rooms at first, then dives or beer joints where he had to fight for his money or fight his way out the door. But he played, fueled by Vienna sausages, whiskey, and uppers, and the next day he rolled out of some little motel, said good-bye to women without names, and drove all day and into the night to play again. Others became footnotes, vanished. He fought, tore at it, one motel room, one bottle, one pill, one song at a time. And it is why, in the early days of his stardom, he would come back onstage when the house was dark and the door chained shut, to play some more. Other musicians on the bill, ones who would be legends, too, trickled back to the stage to sing with him, for that one last encore to the empty seats.

“I want to be remembered as a rock-and-roll idol, in a suit and tie or blue jeans and a ragged shirt, it don’t matter, as long as the people get that show. The show, that’s what counts,” he says. “It covers up everything. Any bad thought anyone ever had about you goes away. ‘Is that the one that married that girl? Well, forget about it, let me hear that song.’”

Hank Williams taught him this, and he never even met the man.

“It takes their sorrow, and it takes mine.”

He looks across the arc of bad-boy rockers who have come after him and laughs out loud; amateurs, pretenders, and whistle-britches, held together with hair spray. But worse, they were not true musicians, not troubadours, who lived on the road and met the people where they lived. He crashed a dozen Cadillacs in one year and played the Apollo. With racial hatred burning in the headlines, the audience danced in the seats to a white boy from the bottomland, backed by pickers who talked like Ernest Tubb. “James Brown kissed me on my cheek,” he says. “Top that.”

In recent years he has recorded two new albums, both critically acclaimed, and both made the Top 100. He did them between hospital visits: viral pneumonia, a stabbing recurrence of his arthritis (in his back, neck, and shoulders, never in his hands), and broken bones in his leg and hip have left him in pain and unable to travel or even sit for more than a few minutes for much of the past few years. But even at his lowest, of course, Jerry Lee was merely between resurrections. In March 2012 he married for the seventh time, to sixty-two-year-old Judith Brown, a former basketball star who had been married to his former wife’s little brother. She had come to help care for him when he was sick. To make the proverbial long story short, he got better. “I didn’t mean to fall in love with him,” she says, “but . . .” They married and honeymooned in Natchez, near the bridge he walked as a boy. By late summer 2013, he was back playing gigs in Europe, booking studio time in Los Angeles, buying a new Rolls-Royce and stopping for Sonic cheeseburgers before driving Judith’s Buick one hundred miles an hour down Interstate 55. The laws of Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and the United States of America have never much applied.

Once, while mulling over a difficult question, he muttered, “This feller’s about to get shot.” And I thought, Well, I’m dead. It was only Gunsmoke he was watching over my shoulder. He’d seen it all before, and he knew what happened next.

“You know, you can load that .357 with .38 shells,” I told him, “and you won’t blow such deep holes in . . . things.” I waited a few flat, silent seconds, knowing I had wasted my breath.

“Naw,” he finally said, “I don’t think I’ll do that.”

One afternoon near the end of it, I told him why I wanted to write his story. I was born in the South in a time of tailfins, when young men with their hair slicked back with Rose hair oil and blast-furnace scars on their necks and arms would thunder down the blacktop with his music pouring from the windows. The great Hank Williams lifted their hearts with “Lovesick Blues” and became a kind of sin eater for their lives and pain. “That’s it,” says Jerry Lee. “Hank got them up off their knees, and Jerry Lee got them to dancin’.” They loved Elvis, too, but there was a softness in him, a kind of beauty the men did not understand. They got Jerry Lee. He was a balled-up fist, a swinging tire iron. My people, aunts and uncles, rode ten to a car to see him in Birmingham’s Boutwell Auditorium in 1964. “I was wild as a buck then,” said John Couch, who made tires at Goodyear. “And he embarrassed me.” His wife, Jo, was scandalized. “They got all over Elvis for shaking one leg. . . . Jerry Lee shook everything.” Juanita Fair, a bird-like member of the Congregational Holiness Church, remembers just one thing, and has to whisper. “He played piano, with his rear end.” They drove home to pipe shops, furnaces, and cotton sacks, somehow lighter than when they left. I told him this one afternoon as heroes sang to their horses and bad men reached for the sky.

“I did it for them people,” he says, though a great deal of the time he did it for him, because without the music, I had come to believe, he would just cease to be, like cutting through the drop cord on an electric fan. In the still, awful nothing, he is just like everyone else. But it was still a fine thing to say. The point is, when he talked about lifting the blues off people, I knew it to be true. In the past, in telling his story, he pretty much cussed out the world. It was like the story of his life was a record warped and stuck on the wrong speed, but left on, anyway, to howl, groan, and hiss. He was, he admits, often a little bit drunk or mad in those days, and he put people on, to watch them twitch or swing on the gallows of his temper and moods. Even today, it can seem that the only people he truly trusts with his legacy are the ones who knocked over seats as they lunged to their feet in the city auditorium, who got their money’s worth in the Choctaw casino, or who begged him for one last song in some airport hotel lounge. Only they will remember him right. “I look at the faces,” he says. “I look out there, and I know. I know I’ve given ’em something, boy, something they did not know was out there in this world. And I know. They won’t forget me.”

In the dark of his room, the rock-and-roll singer watches himself on the big-screen television, watches himself in fifty-year-old black and white do that song about shakin’ that conquered the world, watches the power in that young, dangerous man. He sees the man stab the keys and kick away the bench and lift the audience from its seats to come swarming, twisting, jumping onstage, to close in a tight circle around his grand piano, all of them shakin’ and twitchin’ like he has them on a stick or a string or a jerking rubber band. He sees him vault on his young legs to the lid of the piano as if some outside force just threw him there, as the other young people snatch at him, at his hair, at the hems of his garments. The boys seem about to lose control of themselves and break something or turn over some cars. The women, jerking and sobbing, seem about to faint, or die, or embarrass their mamas. As he watches, the old man’s toes tap, tap, tap in time, and his fingers play the air. “Gr-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r,” he says, in duet with the young man, and grins wickedly. When the song is over and the young man takes his exaggerated bow, the old man settles back in his pillows, content. Then, from the gloom, barely loud enough to hear, comes a soft “Hee-hee-hee.”

Later, on one of those quiet, weary afternoons, I have one more question before we stop for the night.

“Didn’t I hear once that you . . .” But he cuts me off.

“Yeah,” he says, “I probably did.”