Читать книгу At the Close of Play - Ricky Ponting - Страница 12

Оглавление

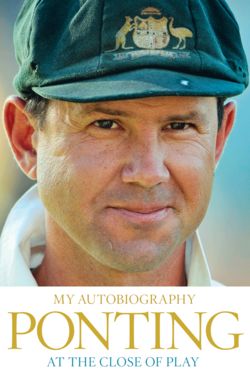

MY NAME IS Ricky Thomas Ponting and I played cricket.

I played junior cricket, indoor cricket, club cricket, rep cricket, state cricket, T20 cricket, one-day cricket and Test cricket. When I didn’t play cricket, I trained to play cricket. I played cricket almost everywhere cricket is played and with some of the greatest players there have ever been. I played in what might have been the best team the world has ever seen. I tried to be the best cricketer I could possibly be. I gave everything I had to that cause from the time I was a small boy until long after most of my contemporaries had walked away.

I was born in Launceston, Tasmania, a small town on a small island state that often gets left off the map of Australia. We’re proud people who look after ourselves and who figure Hobart is the big smoke and the mainland is another country.

My early years were spent in the suburbs of Prospect and then Newnham, where we lived with my grandparents. When we could afford it, we moved to the housing estate at Rocherlea. I played cricket at school and then for the Mowbray Eagles, just like my dad and just like my Uncle Greg who was Mum’s brother. People identify me with Mowbray and that’s all right with me because that is where I learned the game.

I was born on December 19, 1974 to Graeme and Lorraine Ponting. My mum reckons I was a ‘beautiful baby’ but she might be biased. ‘No trouble at all,’ she tells me. ‘Slept and ate, that’s all you did.’ One of her most prominent early memories of me is when I was sitting on the lounge-room floor, eyes fixed on the television, watching Kim Hughes bat. Kim was my first hero in Test cricket, a batsman who, when he was on, was unstoppable. I remember him taking on the West Indies at the MCG the week after my seventh birthday, their fast bowlers aiming at his chest and head, him hooking and pulling fearlessly. That knock stays burned in my memory and probably set the standard for the sort of cricketer I wanted to become. Australian cricket wasn’t going so well then, but he stood up that day and scored 100 out of an innings total of 194. Holding, Roberts, Garner and Croft threw everything they had at him, but he was undefeated at the end of the innings and the Australians went on to win that match. That didn’t happen all that often back then. There was no doubt in my mind, even then, that I wanted to be out there doing exactly the same.

One of Dad’s early recollections of me is not as flattering as Mum’s. ‘When you were three, you used to wait out the front for the children walking home from school, and you’d run out and kick them and then run back inside,’ he once told me. It was, he reckons, one of the first signs of my ‘mischievous’ streak. I’d like to think it showed I was never going to be intimidated by anyone older or bigger and for the next 20 years of my life I always seemed to be the youngest person in the room. I was the boy in the men’s team, the 16-year-old at the cricket academy with Warnie who already had his own car and his own ways, the kid who was missing the final years at school to play first-class cricket, the 20-year-old walking onto the WACA to make my debut in Mark Taylor’s team. Fortunately by then I’d stopped kicking the big kids in the leg …

I have a younger brother, Drew, and a sister, Renee, who is younger again. Today they both live within a couple of minutes of our parents’ place. I’m the only one that went away.

Mum also has strong memories of me always being outside playing cricket as a boy. ‘You always had to be the batsman and Drew had to bowl or field,’ she says. ‘You’d bat for an hour before Drew would get a bat. Then Drew would finally have a go, but he’d only last two minutes and you’d go back in.’ My little brother was the first to suffer for my love. Most batsmen value their wicket, none like getting out, but I took it to an extreme and it all started in the backyard.

Like all kids we built the rules of cricket around the circumstances of our backyard. Over the fence was out and God help you if the old man caught you wading into his prized vegetable patch to fetch a ball. He loved that garden and it lay in wait from point to long-on, ready to swallow a ball. Drew reckons I mastered the art of hitting the ball over the garden and into the fence. I never let him bat for too long because it seemed part of the natural order of things that I was there doing what my hero, Kim Hughes, had done, although with all due respect to Drew he was no Michael Holding. I’d knock him over with my bowling as quick as I could and then take guard again. I have to admit Drew’s ability to bowl endless overs was important to my development and I must thank him some time.

As a kid, growing up, I looked upon Mowbray as being a flash part of town.

We didn’t come from the wrong side of the tracks so much as the wrong side of the river. Launceston is divided by the Tamar river, one side was middle class and nice and the other was where we lived. On our side they had the railway workshops, the factories and all the key landmarks of my early life — at the centre of which was the cricket club. In the Mowbray dressing rooms on a Saturday night they used to tell beery yarns about having to fight to cross the bridge into town, they weren’t true but they told you a little bit about the ‘us and them’ nature of where I came from. Our greatest rivals were Riverside; they came from the nice part of town and sometimes complained that we played cricket too hard. It was a complaint I would hear on and off for a lot of my career, but I never heard them say we weren’t playing fair or honestly.

My father was born in Pioneer, a mining village in the north-eastern tip of the island. His father, Charlie, was a tin miner who wanted a better life for his family so he worked two jobs, digging tin from the ground all week and then travelling to Launceston to dig foundations for houses on the weekends. With the money he made they moved to Newnham. They were people who knew a different life. Dad would tell stories about trapping rabbits and the like so they could eat, and I reckon that his enormous vegetable garden had something to do with that poor background.

The Pontings had arrived in Tasmania back in about 1890. My great great grandfather was a miner, his son was a miner and so was his son, my grandfather Charlie, but Charlie joined the RAAF when the war broke out and that might have changed things. He married Connie, my grandmother, during the war and sometime later they moved from Pioneer into Launceston and that was the last time our family dug for tin.

Pop kept greyhounds and Dad tells the story that he went to the races one night and an owner said to him, ‘You want a dog? I’ve got one that’s no good to me, it can’t win a race.’ Dad walked five kilometres home with the dog and put it under the house. Fed it some steak. His father said he couldn’t keep it, but when Dad came home the next day his father had built a run across the back garden and it all started from there. The dog won its first race and we were away. Or that’s how the story goes.

In Rocherlea Mum and Dad rented a small three-bedroom housing commission home on the bend at 22 Ti Tree Crescent. It was a cottage that had a nice front yard and a reasonable backyard dominated by Dad’s vegetable garden. We were on the edge of town. It wasn’t the best neighbourhood and always had a bad reputation — there were some houses that seemed to be visited by the police on a regular basis and I suppose there was a bit of trouble around but I avoided it. I can’t ever remember our house being locked, which tells you a little bit about how life was.

We didn’t have much money when I was growing up, but I never remember us wanting for anything. Dad left school early to pursue a life as a golf professional, which didn’t work out. He was a great sportsman and I think the interest he took in my life was because he wanted me to have a chance to do the things he didn’t. Dad was a good cricketer and footballer and a better golfer; I suppose you could say he was pushy, but that’s probably too simplistic. Dad saw I was good and did the right thing by letting me know when I could be better. I always wanted to make him proud and never resented the way he encouraged me. He worked at the railways and other jobs, eventually finding his place as a groundsman. He didn’t earn a lot but he loved — loves — the work. Mum and Dad’s life revolved around us kids. Mum worked, but always made sure she or Dad was there for us when we were home. She was raised in Invermay and for most of our early lives she worked at the local petrol station there.

I sometimes think that if I hadn’t dragged them to the odd game of cricket in the past 30 years that they might never have left Launceston.

From our house in Rocherlea, it was about two kilometres south to Mowbray Golf Club, a bit less than a kilometre further to the racecourse, and another kilometre closer to the city centre to get to Invermay Park, the former swampland that would become the home ground of the Mowbray Cricket Club in the late 1980s. That reclaimed land is why people from around this area have long been known as ‘Swampies’.

I am extremely fortunate to have parents who love their sport. My mum represented Tassie at vigoro (a game not too dissimilar to cricket), played competitive badminton and netball, and later in life started playing golf because, as she explains it, her husband was always down at the clubhouse. Taking up the game was her best chance of seeing more of him.

Mum and Dad wanted their kids to be happy, humble, brave and honest. There was a toughness about where I was growing up and my parents never hid me from that, but neither did they use it as an excuse to let me run wild. I was sort of street-smart, and that and a combination of my parents’ love for me and my addiction to all things sport kept me out of serious trouble. There was, though, a bit of rascal in my make-up. One evening I came home late, explaining that I’d been at a mate’s place doing schoolwork, which was in itself a long bow. Worse, my shoes were covered in mud from the creeks at Mowbray Golf Club, where we’d been searching for lost balls that we could sell back to the members. I’ll never forget how Dad belted me as he demanded that in future I tell the truth, and how the message sank in. At the same time, I couldn’t believe how stupid I’d been, not cleaning my shoes before I got home.

Honesty was important to Dad and he passed that on.

I was never top of my class academically, but neither was I near the bottom. In Rocherlea, learning to stay out of trouble was as important as learning your times tables. Some might be surprised to learn I was a prefect for two of the years I was at high school. I suppose that shows that even at an early age I showed some hints that there was some leadership capabilities somewhere deep inside this sport-obsessed kid.

Sport was the making of me. From a very early age I knew I could hold my own at cricket or football, which gave me plenty of confidence and a lot of street cred with boys bigger and older than me. Because of the rules governing school sport in Tasmania at the time I didn’t play any organised cricket or football until grade five at Mowbray Heights Primary School, when I was 10, and I didn’t make my debut in senior Saturday afternoon cricket with the men at Mowbray until 1987, when I was 12. Before then, though, I did take part in some school-holiday coaching clinics, watched the Mowbray A-Grade team play and won a thousand imaginary Test matches against my little brother and whoever else we could recruit into neighbourhood contests.

There were other kids who might have had more material possessions, but living on the edge of town meant we had plenty of open space and in the days before laptops and the like we used it well. It could get icy in winter, but it’s never too cold to kick a footy, and Dad found me a set of clubs when I wanted to hit a golf ball. If Drew and I could get down for a round of golf Mum would pack us a flask of cordial and give us enough money for a pack of chips and we were away. There was always cricket gear around the house and when a group of us went down to the local nets or park we always practised with a fair-dinkum cricket ball.

Mowbray boys learned not to flinch from an early age.

Being born in a small town had its advantages as everything was close and parents never needed to worry too much about where the kids were. If I was missing Mum or Dad just had to find the nearest game of cricket or footy and they were comfortable that even if I was in the sheds with the older blokes that they were all neighbours and friends and they were all keeping an eye on me. I had a BMX bike that I used to ride about town, and often to senior cricket matches involving the Mowbray club, my home team, Dad’s old team, a club that in the years after it was formed in the 1920s used to get many of its players from the nearby railway workshops or the Launceston wharves. I started following them partly because I just loved the game, but also because my Uncle Greg was one of their best players.

Cricket fans know him as Greg Campbell. He’s Mum’s brother, 10 years older than me and a man who had a significant influence on my cricket career. Greg encouraged me all the way and spent a lot of time playing cricket with me, but more importantly he set an example. Looking back now I can see how important it was to know that someone from our family could make the big time, could go all the way from Launceston to Leeds, where he made his Test debut in the first Test against England in 1989. That was a huge day in our lives. Not only was Mum’s brother bowling for Australia, another local hero, David Boon, was playing too. Our little town provided two Test players. It was like Launceston had colonised the moon, although in my world landing in the Australian cricket team was a bigger deal.

Having someone in the family who could do that made the dream of one day doing it myself all the more real. Here was a bloke in the side who had played cricket with me in the back garden. It meant Test cricket was a viable option for people like us. Greg nurtured my interest in cricket and we could get pretty competitive when we played each other. One day, when he thought I was out and I thought I wasn’t, we had to go and ask Dad to come out and decide. The ruling went in Greg’s favour, which didn’t surprise me because he and Dad were best mates, to the point that when Dad coached the footy team at Exeter (a town 20 kilometres north of Launceston) one year, Greg went there and played as well. If there was one thing that could and still does get the men of our family into an argument it’s sport. You should hear Dad and myself when a golf game is on the line. To an outsider these disputes might sound pretty serious. They’re definitely earnest, but it’s just our competitive nature and I suppose it was something that got me into hot water a few times over the years.

One of my strongest memories involving Greg is the day when Mum told me that his Ashes kit had arrived. I flew around on my bike to his house in Invermay to check it all out, to try on his baggy green cap and even his Australian blazer, which was many sizes too big but felt absolutely perfect. He was a hero of mine then and he remains a hero of mine today; he’s a good friend who helped show me the way. Standing in that Launceston house dressed in his gear I knew there was only one way my life was going.

In the early and mid 1980s, when I started watching Greg and his team-mates at the Mowbray Eagles, they played their home games at the ground at Brooks High, the local high school at Rocherlea. Sometimes I’d be down there at nine in the morning, even though the game didn’t start until 11. I just didn’t want to miss anything. It was the same when I joined the team working the scoreboard at the Northern Tasmanian Cricket Association (NTCA) ground during Sheffield Shield games — I scored that gig after I rode my bike down to the ground, found the right person and asked for the job. They paid me $20 a day, but much more important than that, I had a bird’s eye view of the game, the warm-ups, the net sessions, everything.

As I said earlier I loved to sit in the corner of the Mowbray A-Grade team’s dressing room. Some of the tactical talks and most of the jokes went over my head, but at the same time I was absorbing plenty. I saw their loyalty and passion for each other and the game. Not least, I saw how those men played hard and fair, enjoyed the wins and hated the losses, wouldn’t take crap from anyone and always sought to be friendly with the opposition once the game was done. Most times, that mateship was reciprocated and if it wasn’t, we knew who the losers were. Those were lessons in cricket etiquette for me. The men set the standard and they said ‘no matter what happens on the field you shake hands and you have a beer after the game’. It was a tradition in Australian Test cricket but one that all nations were keen on. Once it happened after every day’s play, then it shifted to the end of the Test and later, because everything was so hectic, it became something that you did at the end of a tour. I know whenever we had a drink with the opposition after a series it was a positive experience. Arguments happened on the field and stayed there, relationships were built off it.

If Uncle Greg was my favourite, everyone else in the Mowbray dressing room was a star, too. I’d seen his fast-bowling partners, Troy Cooley and Roger Brown, bowling in the Sheffield Shield. Brad Jones, later my coach when I played for the Mowbray Under-13s, had played for Tasmania Colts. Richard Soule was the Tassie wicketkeeper. A standout was Mick Sellers, a strong burly left-hander who strode out to bat at the start of an innings and whacked the ball all over the place. He used a big Stuart Surridge Jumbo, four or five grips on the handle, batted in a cap and took on the fast bowlers every time. If there was ever a blueprint made of the classic Mowbray Cricket Club player it was Mick. He represented Tasmania in a few first-class and one-day games in the 1970s. He played over 400 games for Mowbray and was the club coach. After he retired, he would still be down at the ground, helping to roll the wicket, put on the covers, anything to help. He remains a legendary figure around the club. He was there, of course, when I came back at the end of my career.

He looked after me in those days when I was a constant in their dressing room. He got me involved when the time was right, and sheltered me at other times. In doing so, he taught me so much. They all did. They were kind and generous men. At the same time, everyone feared playing Mowbray; I could see that from the looks on the opposition’s faces, what they said to each other while we were fielding. A game against Mowbray was a tough day at the office, plenty of words spoken, no quarter given. A lot of what you see in me today is a result of learning the game the way they used to play it. When we were truly at our best other sides hated playing Australia. South African cricket captain Graeme Smith admitted as much once, and while a lot of people took this the wrong way, to me and to the others in the side the point was we would not give an inch on the field.

After stumps, if Dad had come from golf to see how the boys had played, he would put down his beer, and bowl to me so I could try to mimic the shots I’d seen played earlier in the day. At home games, we used a big incinerator drum as the wicket and just the same as when they were bowling to me at school my ambition was to never get bowled. Dad was my first coach, at cricket and footy, and he could be a tough marker, but he wanted me to be a winner and I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

You often read or hear of the so-called bravery of sportspeople who overcome great adversity to win. I’ve certainly seen and been a part of some very brave sporting accomplishments over the years, but I must say that the use of the expression ‘bravery’ is completely over-stated when you are witness to some real acts of bravery in everyday life. Rianna and I have met some of the bravest children and families in our work around the area of childhood cancer. The children, especially, move us. While they fight the most horrible disease in the world, they show incredible resilience to go through their treatment and hopefully survive. Without a doubt, it’s even tougher for the families. Parents and grandparents continually ask the question: ‘Why our child or grandchild?’ They have to be brave for the child while maintaining a sense of normality to support siblings and other loved ones at a time that most of us cannot even start to imagine how difficult it must be. Some of the bravest families we have met had children who didn’t survive the battle with cancer.

In our days of supporting the Children’s Cancer Institute Australia, I stayed in regular contact with a number of children, exchanging text messages and keeping up to date with their progress. Those close to me know that I’m a bit slack at returning text messages but my contact with these children was different — I always made a point of answering straight away. Sadly, in many situations, a message would come through from parents letting me know their child didn’t make it. Over the years, though, we have stayed in contact with many families whose children have survived. One very special child close to our hearts is Toby Plate from Adelaide. I first met Toby and his family on the eve of the Adelaide Ashes Test in 2010. During that series, I had a young cancer sufferer join me at each of the opening ceremonies. Of all the children I met that summer, Toby was the sickest — fighting a brain tumour and undergoing the most intensive treatment. We spent considerable time together that day and he left a lasting impression on me. The next day we stood together and sang the national anthem before the second Test began. Sadly not all the children who stood with me in the anthem ceremonies that summer survived their battle with cancer, but Toby did. We have stayed in touch and last year played cricket together at the MCG with Owen Bowditch, who was with me at the Boxing Day Test opening ceremony that summer. These boys and their families epitomise bravery for me. They are symbolic of what it means to overcome adversity. Not all the stories have a happy ending but the bravery shown by each and every child that is confronted by cancer is overwhelming, to say the least.