Читать книгу I, Rigoberta Menchu - Rigoberta Menchu - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

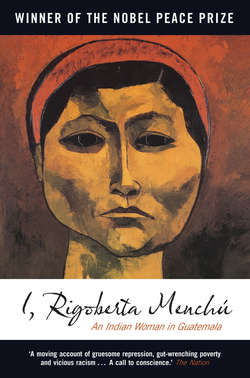

ОглавлениеThis book tells the life story of Rigoberta Menchú, a Quiché Indian woman and a member of one of the largest of the twenty-two ethnic groups in Guatemala. She was born in the hamlet of Chimel, near San Miguel de Uspantán, which is the capital of the north-western province of El Quiché.

Rigoberta Menchú is twenty-three years old. She tells her story in Spanish, a language which she has spoken for only three years. Her life story is an account of contemporary history rather than of Guatemala itself. It is in that sense that it is exemplary: she speaks for all the Indians of the American continent. What she tells us of her relationship with nature, life, death and her community has already been said by the Indians of North America, those of Central America and those of South America. The cultural discrimination she has suffered is something that all the continent’s Indians have been suffering ever since the Spanish conquest. The voice of Rigoberta Menchú allows the defeated to speak. She is a privileged witness: she has survived the genocide that destroyed her family and community and is stubbornly determined to break the silence and to confront the systematic extermination of her people. She refuses to let us forget. Words are her only weapons. That is why she resolved to learn Spanish and break out of the linguistic isolation into which the Indians retreated in order to preserve their culture.

Rigoberta learned the language of her oppressors in order to use it against them. For her, appropriating the Spanish language is an act which can change the course of history because it is the result of a decision: Spanish was a language which was forced upon her, but it has become a weapon in her struggle. She decided to speak in order to tell of the oppression her people have been suffering for almost five hundred years, so that the sacrifices made by her community and her family will not have been made in vain.

She will not let us forget and insists on showing us what we have always refused to see. We Latin Americans are only too ready to denounce the unequal relations that exist between ourselves and North America, but we tend to forget that we too are oppressors and that we too are involved in relations that can only be described as colonial. Without any fear of exaggeration, it could be said that, especially in countries with a large Indian population, there is an internal colonialism which works to the detriment of the indigenous population. The ease with which North America dominates so-called ‘Latin’ America is to a large extent a result of the collusion afforded it by this internal colonialism. So long as these relations persist, the countries of Latin America will not be countries in any real sense of the word, and they will therefore remain vulnerable. That is why we have to listen to Rigoberta Menchú’s appeal and allow ourselves to be guided by a voice whose inner cadences are so pregnant with meaning that we actually seem to hear her speaking and can almost hear her breathing. Her voice is so heart-rendingly beautiful because it speaks to us of every facet of the life of a people and their oppressed culture. But Rigoberta Menchú’s story does not consist solely of heart-rending moments. Quietly, but proudly, she leads us into her own cultural world, a world in which the sacred and the profane constantly mingle, in which worship and domestic life are one and the same, in which every gesture has a pre-established purpose and in which everything has a meaning. Within that culture, everything is determined in advance; everything that occurs in the present can be explained in terms of the past and has to be ritualized so as to be integrated into everyday life, which is itself a ritual. As we listen to her voice, we have to look deep into our own souls for it awakens sensations and feelings which we, caught up as we are in an inhuman and artificial world, thought were lost for ever. Her story is overwhelming because what she has to say is simple and true. As she speaks, we enter a strikingly different world which is poetic and often tragic, a world which has forged the thought of a great popular leader. In telling the story of her life, Rigoberta Menchú is also issuing a manifesto on behalf of an ethnic group. She proclaims her allegiance to that group, but she also asserts her determination to subordinate her life to one thing. As a popular leader, her one ambition is to devote her life to overthrowing the relations of domination and exclusion which characterize internal colonialism. She and her people are taken into account only when their labour power is needed; culturally, they are discriminated against and rejected. Rigoberta Menchú’s struggle is a struggle to modify and break the bonds that link her and her people to the ladinos, and that inevitably implies changing the world. She is in no sense advocating a racial struggle, much less refusing to accept the irreversible fact of the existence of the ladinos. She is fighting for the recognition of her culture, for acceptance of the fact that it is different and for her people’s rightful share of power.

In Guatemala and certain other countries of Latin America, the Indians are in the majority. The situation there is, mutatis mutandis, comparable to that in South Africa, where a white minority has absolute power over the black majority. In other Latin American countries, where the Indians are in a minority, they do not even have the most elementary rights which every human being should enjoy. Indeed, the so-called forest Indians are being systematically exterminated in the name of progress. But unlike the Indian rebels of the past, who wanted to go back to pre-Columbian times, Rigoberta Menchú is not fighting in the name of an idealized or mythical past. On the contrary, she obviously wants to play an active part in history and it is that which makes her thought so modern. She and her comrades have given their historical ambitions an organic expression in the shape of the Peasant Unity Committee (CUC) and their decision to join the ‘31 January Popular Front’, which was founded to commemorate the massacre on that date of a group of Quiché Indians who occupied the Spanish embassy Ciudad-Guatemala in order to draw attention to their plight. The group which occupied the embassy was led by Rigoberta’s father, Vicente Menchú, who has since become a national hero for the Indians of Guatemala. The Popular Front, which consists of six mass organizations and was founded in January 1981, took the name ‘31 January’ in memory of the massacre.

Early in January 1982, Rigoberta Menchú was invited to Europe by a number of solidarity groups as a representative of the 31 January Popular Front. It was then that I met her in Paris. The idea of turning her life story into a book came from a Canadian woman friend who is very sympathetic to the cause of the Guatemalan Indians. Never having met Rigoberta, I was at first somewhat reluctant, as I realized that such projects depend to a large extent on the quality of the relationship between interviewer and interviewee. Such work has far-reaching psychological implications, and the revival of the past can resuscitate affects and zones of the memory which had apparently been forgotten for ever and can lead to anxiety and stress situations.

As soon as we met, however, I knew that we were going to get along toegether. The admiration her courage and dignity aroused in me did much to ease our relationship.

She came to my home one evening in January 1982. She was wearing traditional costume, including a multicoloured huipil with rich and varied embroidery; the patterns were not symmetrical and one could have been forgiven for assuming that they were random. She was also wearing an ankle-length skirt; this too was multicoloured and the thick material was obviously hand-woven. I later learned that it was called a corte. She had a broad, brightly coloured sash around her waist. On her head, she wore a fuchsia and red scarf knotted behind her neck. When she left Paris, she gave it to me, telling me that it had taken her three months to weave the cloth. Around her neck she had an enormous necklace of red beads and old silver coins with a heavy solid silver cross dangling from it. I remember it as being a particularly cold night; in fact I think it was snowing. Rigoberta was wearing no stockings and no coat. Beneath her huipil, her arms were bare. Her only protection against the cold was a short cape made from imitation traditional fabric; it barely came to her waist. The first thing that struck me about her was her open, almost childlike smile. Her face was round and moon-shaped. Her expression was as guileless as that of a child and a smile hovered permanently on her lips. She looked astonishingly young. I later discovered that her youthful air soon faded when she had to talk about the dramatic events that had overtaken her family. When she talked about that, you could see the suffering in her eyes; they lost their youthful sparkle and became the eyes of a mature woman who has known what it means to suffer. What at first looked like shyness was in fact a politeness based upon reserve and gentleness. Her gestures were graceful and delicate. According to Rigoberta, Indian children learn that delicacy from a very early age; they begin to pick coffee when they are still very young and the berries have to be plucked with great care if the branches are not to be damaged.

I very soon became aware of her desire to talk and of her ability to express herself verbally.

Rigoberta spent a week in Paris. In order to make things easier and to make the best possible use of her time, she came to stay with me. Every day for a week, we began to record her story at nine in the morning, broke for lunch at about one, and then continued until six in the evening. We often worked after dinner too, either making more recordings or preparing questions for the next day. At the end of the week I had twenty-four hours of conversation on tape. For the whole of that week, I lived in Rigoberta’s world. We practically cut ourselves off from the outside world. We established an excellent rapport immediately and, as the days passed and as she confided in me and told me the story of her life, her family and her community, our relationship gradually became more intense. As time went by, she became more self-assured and even began to seem contented. One day she told me that until then she had never been able to sleep all night without waking up in a panic because she had dreamed that the army was coming to arrest her.

But I think it was mainly the fact of living together under the same roof for a week that won me her trust; it certainly brought us closer together. I have to admit that this was partly an accident. A woman friend had brought me some maize flour and black beans back from Venezuela. Maize and beans are the staple diet in both Venezuela and Guatemala. I cannot describe how happy that made Rigoberta. It made me happy too, as the smell of tortillas and refried beans brought back my childhood in Venezuela, where the women get up early to cook arepas* for breakfast. Arepas are much thicker than Guatemalan tortillas, but the ingredients are the same, as are the methods of cooking and preparing them. The first thing Rigoberta did when she got up in the morning was make dough and cook tortillas for breakfast; it was a reflex that was thousands of years old. She did the same at noon and in the evening. It was a pleasure to watch her. Within seconds, perfectly round, paper-thin tortillas would materialize in her hands, as though by miracle. The women I had watched in my childhood made arepas by patting the dough flat between the palms of their hands, but Rigoberta made her tortillas by patting it between her fingers, holding them straight and together and constantly passing the dough from one hand to the other. It is much more difficult to make perfectly shaped tortillas like that. The pot of black beans lasted us for several days and made up the rest of our daily menu. By chance, I had pickled some hot peppers in oil shortly before Rigoberta’s arrival. She sprinkled her beans with the oil, which almost set one’s mouth on fire. ‘We only trust people who eat what we eat’, she told me one day as she tried to explain the relationship between the guerrillas and the Indian communities. I suddenly realized that she had begun to trust me. A relationship based upon food proves that there are areas where Indians and non-Indians can meet and share things: the tortillas and black beans brought us together because they gave us the same pleasure and awakened the same drives in both of us. In terms of ladino-Indian relations, it would be foolish to deny that the ladinos have borrowed certain cultural traits from the Indians. As Linto points out, some features of the culture of the defeated always tend to be incorporated into the culture of the conqueror, usually via the economic-based slavery and concubinage that result from the exploitation of the defeated. The ladinos have adopted many features of the indigenous culture and those features have become what George Devereux calls the ‘ethnic unconscious’. The ladinos of Latin America make a point of exaggerating such features in order to set themselves apart from their original European culture: it is the only way they can proclaim their ethnic individuality. They too feel the need to be different and therefore have to differentiate themselves from the Europe that gave them their world-vision, their language and their religion. They inevitably use the native cultures of Latin America to proclaim their otherness and have always tended to adopt the great monuments of the Aztec, Mayan and Incan pre-Columbian civilizations as their own, without ever establishing any connection between the splendours of the past and the poor exploited Indians they despise and treat as slaves. Then there are the ‘indigenists’ who want to recover the lost world of their ancestors and cut themselves off completely from European culture. In order to do so, however, they use notions and techniques borrowed from that very culture. Thus, they promote the notion of an Indian nation. Indigenism is, then, itself a product of what Devereux calls ‘disassociative acculturation’: an attempt to revive the past by using techniques borrowed from the very culture one wishes to reject and free oneself from.* The indigenist meetings held in Paris–with Indian participation–are a perfect example of what he means. Just like the avant-garde groups which still take up arms in various Latin American countries–and these groups should not be confused with resistance groups fighting military dictatorships, like the Guatemalan guerrillas, the associations of the families of the ‘disappeared ones’, the countless trade union and other oppositional groups which are springing up in Chile and other countries, or the ‘Plaza de Mayo Mothers’ movement in Argentina–the indigenist groups also want to publicize their struggles in Paris. Paris is their sound box. Whatever happens in Paris has repercussions through the world, even in Latin America. Just as the groups which are or were engaged in armed struggle in America have supporters who adopt their political line, the Indians too have their European supporters, many of whom are anthropologists. I do not want to start a polemic and I do not want to devalue any one form of action; I am simply stating the facts.

The mechanism of acculturation is basic to any culture; all cultures live in a state of permanent acculturation. But there is a world of difference between acculturation and an attempt to impose one culture in order to destroy another. I would say that Rigoberta Menchú is a successful product of acculturation in that her resistance to ladina culture provides the basis for an antagonistic form of acculturation. By resisting ladina culture, she is simply asserting her desire for ethnic individuality and cultural autonomy. Resistance can, for instance, take the form of rejecting the advantages that could result from adopting techniques from another culture. Rigoberta’s refusal to use a mill to grind her maize is one example. Indian women have to get up very early to grind the pre-cooked maize with a stone if the tortillas are to be ready when they leave for work in the fields. Some people might argue that this is nothing more than conservatism, and that indeed is what it is: a way of preserving the practices connected with preparing tortillas and therefore a way to prevent a whole social structure from collapsing. The practices surrounding the cultivation, harvesting and cooking of maize are the very basis of the social structure of the community. But when Rigoberta adopts political forms of action (the CUC, the 31 January Popular Front and the Vicente Menchú Organization of Christian Revolutionaries) she is adopting techniques from another culture in order to strengthen her own techniques, and in order to resist and protect her own culture more effectively. Devereux describes such practices as adopting new means in order to support existing means. Rigoberta borrows such things as the Bible, trade union organization and the Spanish language in order to use them against their original owners. For her the Bible is a sort of ersatz which she uses precisely because there is nothing like it in her culture. She says that ‘The Bible is written, and that gives us one more weapon.’ Her people need to base their actions on a prophecy, on a law that comes down to them from the past. When I pointed out the contradiction between her defence of her own culture and her use of the Bible, which was after all one of the weapons of colonialism, she replied without any hesitation whatsoever: ‘The Bible says that there is one God and we too have one God: the sun, the heart of the sky.’ But the Bible also teaches us that violence can be justified, as in the story of Judith, who cut off the head of a king to save her people. That confirms the need for a prophecy to justify action. Similarly, Moses led his people out of Egypt and his example justifies the decision to transgress the law and leave the community. The example of David shows that children too can take part in the struggle. Men, women and children can all justify their actions by identifying with biblical characters. The native peoples of Latin America have gone beyond the stage of introspection. It is true that their advances have sometimes been blocked, that their rebellions have been drowned in blood and that they have sometimes lost the will to go on. But they are now finding new weapons and new ways to adapt to their socio-economic situation.

Rigoberta has chosen words as her weapon and I have tried to give her words the permanency of print.

I must first warn the reader that, although I did train as an ethnographer, I have never studied Maya-Quiché culture and have never done fieldwork in Guatemala. Initially, I thought that knowing nothing about Rigoberta’s culture would be a handicap, but it soon proved to be a positive advantage. I was able to adopt the position of someone who is learning. Rigoberta soon realized this: that is why her descriptions of ceremonies and rituals are so detailed. Similarly, if we had been in her home in El Quiché, her descriptions of the landscape would not have been so realistic.

When we began to use the tape recorder, I initially gave her a schematic outline, a chronology: childhood, adolescence, family, involvement in the struggle…As we continued, Rigoberta made more and more digressions, introduced descriptions of cultural practices into her story and generally upset my chronology. I therefore let her talk freely and tried to ask as few questions as possible. If anything remained unclear, I made a note of it and we would spend the last part of the working day going over anything I was uncertain about. Rigoberta took an obvious pleasure in explaining things, helping me understand and introducing me to her world. As she told me her life story, she travelled back in time, reliving dreadful moments like the day the army burned her twelve-year-old brother alive in front of the family, and the weeks of martyrdom her mother underwent at the hands of the army before they finally let her die. As I listened to her detailed account of the customs and rituals of her culture, I made a list which included customs relating to death. Rigoberta read my list. I had decided to leave the theme of death until last, but when we met for the last time, something stopped me from asking her about the rituals associated with death. I had the feeling that if I asked about them my questions would become a prophecy, so deeply marked by death was her life. The day after she left, a mutual friend brought me a cassette on which Rigoberta had recorded a description of funeral ceremonies, ‘because we forgot to record this.’ That gesture was the final proof that Rigoberta is a truly exceptional woman; culturally, it also proved that she is a woman of complete integrity and was letting me know that she had not been taken in. In her culture, death is an integral part of life and is accepted as such.

In order to transform the spoken word into a book, I worked as follows.

I began by transcribing all the tapes. By that I mean that nothing was left out, not a word, even if it was used incorrectly or was later changed. I altered neither the style nor the sentence structure. The Spanish original covers almost five hundred pages of typescript.

I then read through the transcript carefully. During a second reading, I established a thematic card index, first identifying the major themes (father, mother, childhood, education) and then those which occurred most frequently (work, relations with ladinos, linguistic problems). This was to provide the basis of the division of the material into chapters. I soon reached the decision to give the manuscript the form of a monologue: that was how it came back to me as I re-read it. I therefore decided to delete all my questions. By doing so I became what I really was: Rigoberta’s listener. I allowed her to speak and then became her instrument, her double, by allowing her to make the transition from the spoken to the written word. I have to admit that this decision made my task more difficult, as I had to insert linking passages if the manuscript was to read like a monologue, like one continuous narrative. I then divided it into chapters organized around the themes I had already identified. I followed my original chronological outline, even though our conversations had not done so, so as to make the text more accessible to the reader. The chapters describing ceremonies relating to birth, marriage and harvests did cause some problems, as I somehow had to integrate them into the narrative. I inserted them at a number of different points, but eventually went back to my original transcript and followed the order of Rigoberta’s spontaneous associations. It was pointed out to me that placing the chapter dealing with birth ceremonies at the beginning of the book might bore the reader. I was also advised simply to cut it or include it in an appendix. I ignored all these suggestions. Perhaps I was wrong, in that the reader might find it somewhat off-putting. But I could not leave it out, simply out of respect for Rigoberta. She talked to me not only because she wanted to tell us about her sufferings but also–or perhaps mainly–because she wanted us to hear about a culture of which she is extremely proud and which she wants to have recognized. Once the manuscript was in its final form, I was able to cut a number of points that are repeated in more than one chapter. Some of the repetitions have been left as they stand as they lead in to other themes. That is simply Rigoberta’s way of talking. I also decided to correct the gender mistakes which inevitably occur when someone has just learned to speak a foreign language. It would have been artificial to leave them uncorrected and it would have made Rigoberta look ‘picturesque’, which is the last thing I wanted.

It remains for me to thank Rigoberta for having granted me the privilege of meeting her and sharing her life with me. She allowed me to discover another self. Thanks to her, my American self is no longer something ‘uncanny’. To conclude, I would like to dedicate these lines from Miguel Angel Asturias’s ‘Barefoot Meditations’ to Rigoberta Menchú:

Rise and demand; you are a burning flame.

You are sure to conquer there where the final horizon

Becomes a drop of blood, a drop of life,

Where you will carry the universe on your shoulders,

Where the universe will bear your hope.

Elisabeth Burgos-Debray

Montreux-Paris

December 1982.