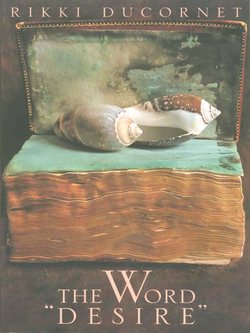

Читать книгу The Word "Desire" - Rikki Ducornet - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Chess Set of Ivory

Chess appealed to my father’s delight in quietude, his repressed rage, his trust in institutions, models, and measured behavior. Chess justified what Father liked best: thinking about thinking. He called it: battling mind.

Father dwelled in a space of such disembodied quietness his Egyptian students called him His Airship, I believe with affection. Chess allowed Father to make decisions that would in no way influence the greater world—beyond his grasp anyway—and to engage in conflict without doing violence to others or to himself. (Father’s fear of thuggery suggested clairvoyance when in a later decade he would find himself undone by a handful of classroom Maoists who called him Gasbag to his face. If clearly they intended to hurt him, they were, admittedly, responding to that disembodied quality of his already evident in Egypt, and his pedantry—a quality rooted in timidity.)

Father was a closet warrior, a mild man and an intellectual, a dreamer of reason in a world he feared was chronically, terminally unreasonable. And he was a parsimonious conversationalist. His favorite quote was from Wittgenstein: “What we cannot speak of we must be silent about.” When Father did speak, he spoke so softly that even those who knew him well had to ask him to repeat himself. Once, during his Fulbright year in Egypt, when several of his students had discovered a crate of brass hearing trumpets for sale in the bazaar, they had carried these to class to—at a prearranged signal—lift them simultaneously to their ears. (Yet, in sleep, Father ground his teeth so loudly my mother nightly dreamed of industry: gravel pits, cement factories, brickworks.)

I could add that Father was fastidious, sometimes changing his clothes two or three times a day. He ate little and dressed soberly—if with a specific, outdated flair: on formal occasions he wore a cummerbund. I took after him, played quietly by myself behind closed doors. And if Mother—and she was a big, beautiful Icelander—was a noisemaker, she made her noise out in the world—the Officers Club, for example.

Father once admitted to me that chess saved him from losing his mind—and this was said after he had lost his heart. When he played he became disembodied—a mind on a stalk in a chair, invisible—and if he could keep ahead of his adversary, impalpable, too. In life as in chess, Father did not want to be touched, to be moved, to be seized; he was unwilling to be pinned down or cornered. He jumped from one discourse to another, embracing peculiar and obscure concepts and ideologies about which no one else knew anything; meaningful conversation with him proved an impossibility. In those years chess became the sole vehicle by which he could be reached, or rather, engaged—for he could never be reached—the navigable airspace in which he functioned was invariably at the absolute altitude of his choosing. When he embraced the cryptic vocabulary of Coptic gnosticism, he lost his few remaining friends because it was impossible to follow the direction of his thoughts, and that was exactly what he wanted.

In Cairo Father played chess blindfolded and invariably he won. The positions of the pieces on the board were sharper in his mind’s eye than the furniture of his own living room (where he was constantly scraping his shins and knocking over chairs).

But I keep digressing. What I wish to write about is a brief period of time in Egypt, one year that seems to stretch to infinity, a year in limbo, a time of disquiet and loneliness. That year was a paradox—both intensely felt and numbing. The world passed before my eyes like an animated stage—distant, colorful, unattainable—and I, in my own little chair, looked on, watchful and amazed, frightened, enchanted, and disembodied, too.

In Egypt, Father had taken to wearing a fez to wander as unobtrusively as possible. He looked Egyptian—we both did—so that Cairo embraced us unquestioningly, my father’s limited but convincing Arabic sufficing during brief encounters with beggars and merchants and dragomen; and he spoke French.

One winter’s day on an excursion to the Mouski, we passed the window of an ivory carver’s shop, which contained any number of charming miniatures: gazelles, tigers, monkeys, elephants, and the like. As he gazed at the animals—and I supposed that he might elect to buy me one—Father began to cough and hum in a familiar way that meant he was about to make a brilliant move, or was excited by an idea. At that instant a small boy invited us into the shop and offered us two little chairs on which to sit. The carver appeared then, beaming, and sent the boy off to fetch coffee. The tray set before us, the mystery of Father’s excitement was revealed: If Father provided the drawings, could the carver make for him a chess set in which the goddesses and gods of the Egyptians and the Romans met face-to-face? Isis and Osiris, Horus and Amon Ra battling Jupiter and Juno and Neptune and Mars? Might sacred bulls confront elephants? He imagined the Egyptian pawns as ibises and the Roman pawns as archers.

This conversation took place in a boil of English, Arabic, and French; already the coffee tray was cluttered with sketches and ivory elephants—examples of sizes and styles. As the ivory carver and my father discussed the set’s price and the time necessary for its completion, I sipped sherbet and explored the shadows. I found a stack of tusks as tall as myself and two pails: one contained ivory bracelets soaking to scarlet in henna and the other ivory animals soaking to the color of wild honey in black tea. As I looked the boy came over and with a flat stick stirred the carvings gently, all the while gazing at me with curiosity.

The shop was very old and smelled unlike any place I had ever been; I suppose it was the ivory dust on the air—all that old bone—the henna, the coffee, and the tea. It was a wonderful smell and soothing, so that for several instants I closed my eyes and slept.

When I awoke the boy had vanished, leaving ajar a little door that opened onto the back alley. The alley led to a quarter entirely devoted to leather slippers stained green, and further down an antiques seller’s where I had seen a figure of hawk-headed Horus, the god of the rising sun, made of Egyptian paste and the size of a thumb. It had come from a tomb near Luxor.

The little figure had spoken to me with such urgency that, for the first time in my young life, I had dared ask my father that he buy it. He did not take my request seriously. How could a ten-year-old possibly fathom the value of such a thing? Not that it was impossibly expensive—for in those days such pieces were still to be found easily enough on the market. But it was three thousand years old and Father imagined a troubling eccentricity of character: my request seemed excessive. Had I inherited an immodest desire for luxury from my mother, who at that moment was having the hair removed from her armpits with hot caramel? (His own delight in luxury he did not question because compared to hers it was so tame: a collection of chess sets, a few articles of elegant clothing.)

Mother’s extravagance and acute blondness were striking anywhere, but above all in Egypt. When in gold lamé she arrived late at a reception at the University Club, a hush descended upon the room. She preferred officers and had befriended a number of the Egyptian brass (including the young Nasser)—handsome men flourishing thick mustaches.

I was learning Arabic. To my delight I discovered if I said egg’ga I got an omelette, and salata, a salad. Father owned a charming little pocket dictionary with words in French, English, and Arabic, and incongruous illustrations of disparate objects. One page showed a Victorian piano, a British bobby, a sarcophagus, two sorts of cannon, a hula dancer, a radio singer, a caged tiger, a man singing in blackface, an airplane, a hand holding a pen, a pearl necklace, a salted ham, a taxicab, a star, a cobra, and a hat.

Each week my father and I returned to the ivory carver’s shop, where the finished pieces accumulated. The Roman castles were Pompeian elephants decked out exactly as in an old print Father had hunted down in the university library; the print was based on a bas-relief uncovered in Pompeii. The little elephants had tusks that ended in spheres the size of small peas. These might be gilded and if they were: should Isis wear a gold necklace and Amon Ra a gold sun? No. Father was after simplicity. The Egyptians should be soaked in tea to darken them and this was all.

As he spoke my father fingered an Osiris four inches tall and completed that morning. He had the lithe body of a young, athletic man and the noble head of a falcon. In guise of a crown he wore the solar disc encircled by a serpent, and in his hand he carried the Key of Life. Father said to me: “When Osiris was torn to pieces and his body tossed to the four winds, Isis, his beloved, searched the world until she found every part but the phallus, because it had been swallowed by a fish. She made him another—of precious wood or alabaster, no one knows. Then she laid his broken body on a perfumed bed and embraced him until he was whole again. And here he is!”

Smiling, Father raised the little figure to the sun that in its passage across the sky had suddenly filled the shop with light. Then, under his breath, he said with a bitterness so unique, so unexpected, that I was profoundly startled: A thing that would not have occurred to your mother.

Alone on my balcony in the afternoon, I would gaze out over the courtyard below, where Bedouins often camped. I could smell baking bread and hear the children singing. I loved to see the women suckle their little ones, and when the girls danced fearlessly I danced too, for in that quiet air the sound of their flutes and drums readily reached me.

They came because of the public water fountain and an ancient sycamore tree that kept the courtyard shady and cool. At its roots the Bedouins had nested their goallah or water pots, and I thought the word wonderful because it contained their word for God. I found a picture of a goallah in the Dracoman, in a series including the sugarloaf-shaped hat of a dervish and a head of lettuce.

I would also gaze at the beautiful balconies across the courtyard, all pierced with patterns of stars. Sometimes a wood panel slid back and the small face of a child might appear, or that of a woman unveiled, her face impossibly pale, her eyes like the eyes of a caged animal, her throat and wrists circled in silver.

I had left all my toys behind but for a small box of glass and porcelain animals, and a green cloth I pretended was a vast meadow. But I was swiftly outgrowing these things. They paled beside the demands of my own slight body, awakening—I did not know to what, except that when each night I found pleasure beneath my small fingers, pleasure detonating like some sudden star, I imagined a blue man beside me, a blue man with the beautiful face of a bird of prey.

Today when we arrive to see the finished Osiris, the ivory carver is full of news. Just this morning in Alley of Old Time, a dervish sliced his belly open and revealed his entrails. A large number of people had gathered beside the carver’s shop to throw coins at the dervish’s feet and cry: Allah is great! Praise Allah! But even more extraordinary, the dervish had spontaneously taken his guts in both his hands and lifted them as though for the carver’s inspection, before asking for a needle and thread to sew himself up again. After, he had limped away to die or to recover—“God,” the carver says, “alone knows.” The blood—and there was very little of it—was not washed away because the spot was considered by some to be holy ground. The ivory carver is eager to show us the blood, but Father at his most imperious says: “L’extase ne m’interesse point.”

The next hour is characterized by silence, Father examining the new piece with extreme attention, the carver bent over his work—Jupiter—with exemplary intensity. Later on, as we are making our way back to Khan el-Kaleel to hail a cab, we turn off too soon and, wandering in an unfamiliar maze of streets, find ourselves among the butchers’ stalls, where Father bumps into a table piled high with several dozen skinned heads of sheep, shining with oil and ready for roasting.

Suddenly I see my father’s fez rolling along the street and then Father bent in two and vomiting, spattering the knees of his white linen suit with filth. He vomits violently, in spasms, as little boys looking solemn gather in droves and one stunning man in a white turban offers my father a handkerchief moistened with orange-blossom water. Panting, Father grabs this to mop his face and I see a wild look in his eyes, the look of the woman at the window of stars. Then, somehow, we are in a taxi speeding home, the generous man whom we will never see again diminishing like a genie behind us.

Throughout the ride Father’s face remains plunged in the scented handkerchief. When we arrive at our building’s gate, Father raises his eyes and I see that he is still terrified. He needs help counting change. For a moment he opens his mouth as if to apologize but says nothing, as though speaking demands too great an effort. To this day I cannot smell orange-blossom water without thinking of a cobbled street, a spoiled fez, my father’s stained knees.

Father was ill for two months. A fever pinned him down so that he could barely move. When he was delirious he raved that the head of gravity lay upon his heart and that it was made of oiled lead. He imagined that the Colossi of Memni had fallen onto his bed and were crushing him, that his own temple was filling with sand. In the fall we had seen stray dogs worrying the corpse of a camel. Father believed he was that camel.

He said he was being pulverized by Time—he spoke as if Time and Gravity were divine beings who despised him because he was merely mortal and made of frangible clay; those were his words: frangible clay. Finally—and this happened in May—his fever broke, his mind cleared, his mood lightened. Father began to mend. Within days we were able to walk to his chamber’s balcony, which overlooked the street, to stand together cracking melon seeds between our teeth and tossing sweets to the organ grinder’s monkey, who, when the music was over, pulled a tin plate from his pants, and a fork.

The following week Father was back to his desk catching up with his classwork and his correspondence—he was at war with a dozen chess players in other countries. I was “Keeper of the Inkpot.” Father teased: Should I spill any, or fail to fill his precious Mont Blanc correctly, I would be shipped off directly to the crocodile-mummy pits of Gebel Aboofayda! (The crocodile-mummy pits were illustrated on page 38 of the Dracoman, along with a fountain pen and a straitjacket.)

Now that Father was on his way to total recovery, we returned to Alley of Old Time to collect the completed chess set. It was splendid. Each Roman archer had distinct features, with bow lowered or raised, minute quivers (and these would soon be broken) in place. The stances of the ibises were variable and capricious: One was nesting and another about to take flight. Yet another, poised on one leg, was fishing, and one held a fish in its beak. Isis was very lovely—lovelier than Juno, who had a stern expression and a large hooked nose. Isis had two diminutive breasts; her soft belly was visible beneath the folds of her gown.

After we had admired the set at length and been served coffee—and I was given a special treat, a square of pink loukoum Studded with pistachios and rolled in powdered sugar—the set was placed in its box, wrapped in brown paper, and tied with string. Then, as we departed, the ivory carver displayed a prodigious tenderness for my father by suddenly kissing his sleeve. We stepped out onto the street. It had been freshly watered and beneath the tattered awnings we walked in coolness.

“Before returning home,” Father said, “let us pay a visit to the little Horus you once so admired. I imagine it is still vegetating in Hassan Syut’s shop.” This was such an unexpected delight that for an instant I stopped walking and leaned against my father’s side, my arm about his waist.

The Horus was no longer there. It had, in fact, been sold some weeks earlier. However, Hassan Syut had something very unusual to show my father and he went to the back of the shop where he sorted through a multitude of pale green boxes. He returned to the counter with an object wrapped in white linen, and with a flourish revealed a blackened piece of mummy. It was a hand cut off at the wrist, a child’s hand carbonized by a three thousand years’ soak in aromatic gum. It was a horrible thing, and my father let out a little cry of displeasure, perhaps despair: Que c’est sale!

For a reason unfathomable—for still I do not know my father’s intimate history—Father was convinced the hand had been offered with malicous intention. “And you still a child,” he said. “Si fragile!” We were making our way past row after row of green slippers. “Everywhere evil!” I thought I heard him say. “Partout . . . le mal!”

His voice was altered; he had begun to bleat as on occasion when he lost patience with my mother, and I, in the still of the night, would hear her return from the mystery that kept her so often away. On such nights it seemed to me that Mother’s orbit was like that of a comet. Light years away, when she approached us it was always on a collision course.

Father’s words came quickly now; they spilled from his mouth with such urgency I could barely follow: “Evil is a lack, you see,” I thought I heard him say. “A lack, a void in which darkness rushes in, a void caused by . . . by thoughtlessness, by narcissism, by insatiable desire. Yes, desire breeds disaster. De toute façon,” he said now, suddenly embarrassed, “those old bodies should be allowed to rest.” I looked into his face. It seemed the hand had designated the darkest recess of his heart and had torn the delicate fabric of his eyes, for his eyes waxed peculiar, distant and opaque: minerals from the moon. I wondered: If a word was enough to create the world, could one artifact from Hell destroy it? The hand, reduced by time to a dangerous, an irresistible density, seemed, in the thinning air, to hover over us.

Father pulled a handkerchief from his vest pocket and pawed at his face. I believe I heard him mutter: “There is no rest.” What did he mean? He hailed a cab and I was aware that I dreaded going home.

The cab smelled of urine, and the windows—covered with a film of dust and oil—could not be rolled down, so that we traveled in a species of fog. When we arrived I helped Father from the cab and held the gate open. When was it, I wondered, that he had become an old man?

The elevator was paneled with mirrors and the embrace of infinity vertiginous. I shut my eyes. Stepping into the hall, we heard music, and then, behind the door, Mother’s thick voice, her voice of rum and honey, came to us; she was singing: I made wine . . .

Father did not ring but instead, holding the ivory chess set against his heart with one arm, fumbled for his keys.

From the lilac tree . . .

He was breathing with difficulty. I feared he was about to die. But the door was open now, and in a room flooded with the full sun of the late afternoon, Mother, her wet hair rolled up in a towel, was dancing, her naked body pressed to the body of a stranger. Seeing us, she held him to her tightly, and, her face against his chest, began to laugh—a terrible laughter that both extinguished the day and annihilated my father and me, severing us from her and from ourselves.

When my father took my hand, the chess set fell to the floor, seemingly in silence so loudly was the blood pounding in my ears. Father held my hand so tightly that it ached, an ache that was the ache of my heart’s pain, exactly.

Wormwood

for Steve Moore

Gran’père was dying, and p’tit Pierre stood at the door clutching his cap, clawing at the rim in his terror and excitement. P’tit Pierre was not yet nine and in the light of the lantern his face was very small and white—like a lima bean. M’man ran for her shawl and the two of us set off after p’tit Pierre, who was walking very fast, already a good way ahead. M’man and I were wearing our nightgowns and slippers; we had to walk carefully else stub our toes on the cobbles. M’man called out: “Allez! Pierre! Pas si vite!”

It was very dark and foggy. We chased after p’tit Pierre’s lantern, which blinked like the Devil in the distance, and once I stumbled. When we reached the gate where Old Owl Head lived in her tiny room above the street, I was frightened and tried to take M’man’s hand, but she pulled away. “Slow down!” she yelled at p’tit Pierre again. “Brigand!”

Walking as fast as we could, it took us twenty minutes to reach Gran’père’s. We could hear his raving even before Margarethe opened the door. I was afraid to go in; the house was transformed by Gran’père’s terrible cries. M’man prodded me, her knuckles hard in my back: “Allez! Allez! Depêche-toi, Nanu!” We followed Margarethe up the stairs and the closer we got to Gran’père’s room, the louder the sound he made. I thought: What if he’s already in Hell? Pulling back, I collided with M’man. “Merde! Nanu!” she cried. “Je me fâche!” I hid my face with my hands because I feared she would strike me, but she only pushed me into the room, which was dark except for Gran’père’s head lit as if from within by Margarethe’s lamp. She set it down on the bedstand beside Gran’père’s teeth and offered M’man a chair. Gran’père could have been dead but for all the noise he was making.

“P’pa!” M’man shouted. “P’pa!” Gran’père snorted and smacked his lips. “He’s thirsty,” M’man decided. Dipping the edge of her shawl into his glass she squeezed some water into his open mouth. “Rah!” he said. “Oui!” said M’man. “C’est moi, Reine. I’m here beside you: Reine.” A strange sound came from Gran’père—like a bullfrog’s croaking—so that I laughed out loud. “Nanu!” M’man made a slicing gesture across her neck. This sobered me enough to approach Gran’père. “Gran’père,” I said. “It’s me, Nanu.” Gran’père said, “Nah?” “Si!” I said. “Nanu. Your little Nanu.” When he did not respond I asked M’man: “Does he know us?” “Shut up!” M’man said. “Conasse!” I wanted to cry then so I looked around the room for my own place to sit. I found Gran’père’s chair beside the desk where in the old days he went over his accounts. For a time I sat there in the dark, staring at the ugly statuette Gran’père called Wormwood. His nose and tongue and knees horribly protruding, Wormwood was sitting on a stump.

Gran’père was asleep and as he slept he whistled: a sound as monotonous as the wind. Downstairs a clock ticked; I could hear M’man’s soft breathing and from time to time I heard her sigh: “Ah, merde. Merde, merde, merde.” She was almost singing.

On the desk there was a little china vase and because it was too deep to see inside I emptied it into my hand. Some pen nibs tumbled out, two coins, and a key. I slipped the coins in the pocket of my nightgown and examined the key. It was very small and appeared to be made of green brass. I held it in the palm of my hand and, making a fist, squeezed hard. When I opened my hand I could feel the key’s impress in my flesh with the tips of my fingers.

Once when I was a tiny child I had asked Gran’père why he kept a thing as ugly as Wormwood around. “If Wormwood were mine,” I told him, “I would throw him into the fire.” Gran’père said: “Little idiote! Wormwood is made of brass and cannot burn. But he has a hot temper: behave yourself, Nanu, or he’ll wake up—because yes, even though his eyes are open he is fast asleep. If I decide to wake him, you’re finished, Nanu! Foutue! Foutue! Fucked, petite garce. Tu comprends?”

Remembering this, I bit my lip, but what I really wanted to do was bite Gran’père. I imagined creeping across the room and poking my head under his covers. Before he or M’man would know what was up, I’d have taken a good bite out of Gran’père. And because the room was dark, Gran’père asleep and M’man sleeping too, I stuck out my tongue. I stuck it out so far it touched the bottom of my chin and still I had not stuck it out far enough. Then I saw p’tit Pierre standing inside the door. Made fearless by the dark and the fact that Gran’père was dying, he crept over to me. His mouth hot against my ear, he said, “I saw you! If le père Foucart doesn’t die I’ll tell him! I’ll tell him I saw Nanu making faces in the dark. And then I’ll watch him give you a good spanking with his shoe.”

I said, “I don’t give a fuck.” P’tit Pierre grinned. He said, “Can I kiss you? You are so pretty, Nanu.” I said, “You make me want to shit you are so ugly.” P’tit Pierre began to laugh. I could hear him laughing quietly beside me in the dark. Then, crouching down, he waddled like a dwarf around the room, sidling dangerously close to M’man’s chair and Gran’père’s bed, looking droll and sinister, too. Once more he was standing beside me. He picked up Wormwood and the china vase, scattering the pen nibs on the table.

“There’s a key,” he whispered. “Help me find it.” I said, “Why? Why should I help you find it? You’re nothing but a little thief.” I was squeezing the key so tightly my hand was throbbing. “Because,” he said, “it’s a thing le père Foucart showed me.” And he imitated Gran’père’s voice so well the hair stood up on the back of my neck: “P’tit Pierre! Viens! Look at what old Wormwood knows how to do! And better than you, I warrant, little brigand!”

In the dark room, M’man softly snoring and Gran’père whistling like the Devil, I said, “Hush! You sound just like him! I’m afraid! Stop or I’ll do it in my pants.”

P’tit Pierre fell to his knees and then, his fist in his mouth to keep the laughter deep in his belly, he rolled across the floor. I could hear Margarethe stirring in the house just under us. “Are you going to sleep here?” P’tit Pierre, now at my feet, gazed up at me.

“Bien sûr! Idiot! Gran’père is dying. I have to stay till he’s dead.” P’tit Pierre then said very seriously: “Nanu . . . I’ll be your husband one day.” I said, “Non! M’man told me we can’t be married because your m’man is a maid who empties Gran’père’s bedpan.” Hurt to the quick, p’tit Pierre growled: “Your papa has run away! You’re no better than a bastard like me.” “My papa did not run away!” I pinched p’tit Pierre’s arm so hard he cried out, waking my m’man. “Hush!” she scolded. “Hush, Nanu. Or I’ll burn your tongue in the fire!” But almost as soon as she said this she was asleep.

“My papa is a soldier,” I said. “He’s fighting the boche. When he comes home he’s taking me to Holland,” I said. It seemed to me p’tit Pierre was crying. “We could elope,” I said, “and live deep in the woods on the hill. No one would look for us there. We’ll eat berries—”

P’tit Pierre was beaming. “And nuts and wild partridge eggs,” he said. “We’ll sleep in a big pile of leaves.”

“I’ll make us a blanket of moss,” I said eagerly. “And when we have babies I’ll kiss them over and over.” As p’tit Pierre looked on I held an imaginary baby in my arms and covered it with kisses. P’tit Pierre bent over me, kissing the air.

“We’ll sleep in a bed of roses,” he said, recalling a song he had heard in the street. “We’ll burn frankincense like they do in church.”

“Roses!” I pretended to spit. “Where will you find roses?”

“In Iron Corset’s garden,” he said gleefully.

“I don’t want my m’man’s roses,” I said, and I pulled his hair.

He said, “I’ll make you a bed of fox fur. And when the werewolf comes I’ll chop off his head.”

“When I am a woman,” I said, “I’ll run away for sure.”

“When I am a man,” p’tit Pierre said, “I’ll shit without dropping my pants.” We both collapsed on the floor, silently laughing. Then for a time we lay together and I could hear p’tit Pierre’s heart moving beneath mine.

Because of M’man’s violent temper and the injury caused by Papa’s departure, to recall the past meant upheaval and isolation. But that night in p’tit Pierre’s arms I dared remember an afternoon when Papa and I climbed the hill up to the Bosc du Puy. At the top we rested beneath the ancient trees. We saw a fox pass by, a glassy-eyed rabbit thrown over its back. We saw a snake, green and gold, its eyes gold, moving among the roots and leaves.

Papa was a geologist—he worked for the mines—and that day he told me about the creatures that were buried when the hill was formed. He said we sat at the foot of a tree rooted in a soil black with volcanic ash and the bone dust of woolly rhinos and horses no bigger than cats. He described the water volcanoes of Iceland, the volcanic bombs of Vesuvius, the eruption of Mount Pelée in Martinique caused (or so some said) by an unusual conjunction of the sun and moon. And although it was a story I had heard before, Papa described the whale skull his own father had found digging a wine cellar deep in the yellow clay under rue Dauphine. The famous naturalist Lamanon had rewarded my great-grandfather with a kiss.

“One day I will take you to Holland,” Papa had said, tenderly stroking my hair. “The skull sits alone in a hall of the Teyler Museum.” After a moment’s reflection he added: “The hall is the size of this wood.”

I was roused from this memory, so like a reverie, by Gran’père’s snores. They sounded like a knife shaving bone. M’man’s snores made the sound of a glue pot simmering. I knew that because once I had helped Papa make glue with the hoof of a horse.

“Fais-moi peur, Nanu!” p’tit Pierre whispered in my ear.

“I can’t. Not with them so near.”

“Yes you can! They are both as good as dead. Start like this: ‘The voyage was doomed from the start.’ ” He nuzzled my neck.

“The voyage was doomed from the start,” I began, and p’tit Pierre sighed with pleasure. “A week off the Java coast the ship was swept by plague and all the sailors died.”

“The stench was terrible,” p’tit Pierre agreed. “All the sailors died but one.”

“And this is his story.”

“L’histoire du marin qui se trouvait seul.”

“All his friends were dead and all his enemies too. And now—”

“Sometimes people die of loneliness, Nanu.” Solemnly, p’tit Pierre licked the inside of my elbow.

“Stop that!” I scolded. “You’re like a little dog!” He licked me again.

“A lion,” he corrected me. “A lion. Lions lick each other. Then what happened?”

“He couldn’t manage the ship. The sails were down and he was at the mercy of the tides. There were roaches in the crackers and the water was black.”

“He could fish—”

“The fish were all too big to catch. Off Java the fish are as big as elephants.”

“He ate shit and he was lonely.”

“So lonely one day he shouted into the wind: ‘Goddamn! I’d take the Devil for a bride!’ ”

“He shouldn’t have said that! Your sailor—quel con!”

“He had an inspiration—”

“What’s that?”

“He thought: An entire wood was cut down to fill the hold of this ship with sandal, ebony, and cedar. I’ll find a nice log and cut off a piece and carve a bride for myself.”

“Like Pinocchio! Pinocella! Pinocella!”

“Shut up, idiot. Not like that. You’ll see. . . . He took a lantern and made his way down into the hold.”

“It was dark and full of rats! God knows what else!”

“Pierre—tais-toi. Some logs were loose and rolling. It was dangerous down there. But he climbed a pile as high as a hill and looked until he found something he liked. With his ax he hacked away until he had a piece about one meter long. The wood was so hard that each time he struck it he made sparks! And it was as dense as lead. Even his small piece was too heavy to lift. He struggled with it until he lost patience and gave it a kick.”

“Saying, ‘Goddamn it! Goddamn it! Goddamn it!’ ”

“The log rolled with the sound of thunder, and when it hit the floor the whole ship shuddered. He scrambled down after it and saw that the log had split wide open. The heart of the wood was green. Green as a corpse.”

“I’m scared, Nanu. . . .”

“And it smelled queer. But he was a stubborn man. He heaved it up to the deck and began to carve. He made so many sparks he needed no lantern to work by. It took him six days to cut her rough form: her head, her body, her arms—”

“He made her beautiful, Nanu.”

“—and it took him seven days to carve her features: her eyes, her lips, her little teeth.”

“Thirteen days for bad luck!”

“When he was finished she was beautiful. He kept her beside him and at night he held her close.”

“He called her Plaisance.”

“That’s stupid! Plaisance! What are you thinking? No. He called her . . . Amadée.”

“Si. C’est mieux.”

“Amadée. But, now listen to this, that wood was strange. It was the strangest wood in the world. Because even though it had taken him ages to carve her face, hour after hour, her features had a life of their own. Soon his little bride’s smile was a sneer. The expression of her eyes changed also. Deep lines appeared—on her forehead and beside her nose and mouth. One morning when he woke up, Amadée was so hideous he threw her away in a corner where the ropes—”

“Coiled like snakes!”

“That night he went to sleep alone.”

“Le pauvre, pauvre con!”

“And he had nightmares. In the middle of the night he woke up screaming—”

“A rat! He was bitten by a rat, eh? Nanu?”

“He thought it was a rat. Until he lit his lamp and found Amadée back in his bed, scowling like a shark—”

“Green as death!”

“Cold to the touch. Cold—”

“As ice, Nanu!”

“Colder. Cold as brass. He picked her up—”

“Although she was so heavy he almost ruptured his kidneys, le pauvre connard—”

“—and he threw Amadée into the sea.”

“The sea swallowed her up whole! C’est fini?”

“Non. That night, a strong current pulled the ship back to the Java coast. In the moonlight the sailor saw that the ship was heading toward some immense rocks, so he dropped anchor. But the sea was too deep!”

“Bottomless! And Amadée sinking and sinking!”

“Helpless, he watched as the rocks—”

“Shining in the moon, black as Hell . . .”

“—loomed closer. Mountains of black stone.”

“There was a sound! Like teeth tearing into the belly of a whale!”

“The ship shuddered and dipped. Water bubbled up everywhere. When the ship rolled over, the logs in the hold broke loose—”

“An entire forest!”

“—shattering the ship.”

“Like a matchbox!”

“As the ship sank the sailor was spat into the water. He was crushed against the rocks by the trees that boiled and leapt in the sea. Just before he died he saw Amadée floating past—but fast. Churning the water! Like the Devil speeding back to Hell! But it wasn’t Amadée any longer—”

“It wasn’t? It wasn’t? Who was it?”

“Wormwood.”

“Wormwood!” P’tit Pierre took my hand and held it against his heart, which was wildly beating. “Tu m’as fait grand peur, Nanu,” he said. “I am so afraid!” For a time he was silent, brooding. “Nanu?” he whispered then, his voice tremulous. “He’s here, in this room with us now!”

“Je sais

“Nanu?”

“Be quiet now, Pierre.”

“How did le pére Foucart get him?”

“Because he is evil, “I whispered.

“Yes, but how did he get him?”

“Once a beggar came to the door wanting bread. It was winter and he was near dead with cold and hunger. ‘Fuck you!’ said Gran’père. ‘Why should I give you bread?’ The beggar pulled Wormwood out from under his rags. ‘I’ll give you this for a piece of bread,’ he said. ‘He’s a precious thing . . . very, very old. . . ’ ”

“And it does a trick! But you know, Nanu . . . le père Foucart won Wormwood at the fair in St. Firmat.”

The shadows in our corner of the room dispersed for a moment; it was Margarethe, come in with a candle. Looking up I saw her standing over us, her breasts like loaves of good, round country bread.

“P’tit Pierre!” she whispered, bending down and tugging at his sleeve. “Get up and go to sleep! Nanu, you come too. I’ve made a bed for you in the kitchen.” I said, “Non. I want to stay here with M’man and Gran’père.” “Bien,” she said. She took off her shawl and put it across my knees. Then she went to the cupboard and fetched a pillow. When she gave it to me I told her it smelled like sour milk. “Sour milk?” she said. “What will you dream up next? I’m going to sleep for a few hours if I can. Le père Foucart has kept me up for two nights in a row. Come and get me, Nanu, when he’s near the end.”

M’man snorted in her sleep and Margarethe winked. “You’ll come for me?” I nodded. My hand ached because I had been squeezing the key. I said, “Margarethe? After he is dead and I am sleeping, will I see his face behind the flames?”

“Only if you are bad, Nanu.” She left the room, taking p’tit Pierre by the hand.

For a time I lay there on the floor. Then, because I could not sleep, I went back to the desk and picked up Wormwood. He was not very large—maybe thirty centimeters tall—but being made of solid brass he was very heavy. It was too dark for me to see where to put the key, so I rubbed Wormwood’s base and felt where his toes curled into the bark of the stump; I rubbed Wormwood’s skull and ears, and I put my finger into his mouth. At last I found the place—a small hole in Wormwood’s back, between his shoulder blades. I slipped in the key and slowly wound Wormwood up. A small sound came from him, a little like the sound a clock makes before it strikes the hour, only far fainter. And then I saw Wormwood’s penis—invisible before—rising between his thighs like a great green finger. Slowly, slowly it rose, revealing a majestic set of balls. At that instant Gran’père seemed to crow and M’man, waking, cried out: “What is it?” Springing to her feet, she stood over Gran’père shouting, “What is it? What is it?” I put out my hand to hide Wormwood’s penis but there was no need; it had vanished.

Magarethe came running up the stairs and p’tit Pierre too; suddenly there was a commotion in the room as though a flock of birds was feeding there or a flock of sheep on their way to slaughter, bleating. My heart was in my throat and I could think of nothing but winding Wormwood up again. M’man called to me then: “Vite,” she cried, “Hurry, Nanu! Come to your Gran’père’s bedside right away, because he is dying. Come here at once, Nanu.”

“He’s dead,” Margarethe said even before I reached him; and as M’man and I looked on she tied Gran’père’s jaw shut with a handkerchief. He looked very odd—as though he’d just had a tooth pulled—and I could tell that p’tit Pierre was thinking the same thing.

Then Margarethe walked to Gran’père’s desk. Overturning the china vase she said: “There were two coins; where are they? Did you take them, Nanu?” M’man shrieked: “Give them back! Otherwise we cannot close his eyes!” and she grabbed me by the arm. Terrified, I pulled the coins from my pocket. When M’man slapped me—and she slapped me hard—the key flew from my hand, flashing once in the lamplight as it fell, flashing once again as it hit the floor.

Roseveine

for Harry Mathews

Our name is Gabriel Temporal-Lux-Blason, son of Hermine Temporal-Lux and Gerard Blason: Phallic Instrument of French Imperialism, for fifty years actively dangerous, gaga for ten and now defunct. As We tackle this memoir, Hermine weeps and Gerard seeps into mud.

Simple names are never good enough and this is why Hermine Temporal-Lux is also called “the Angel of Patience” and Gerard Blason “the Butcher of Madagascar.” These designations serve to preface the following: If We are Gabriel Temporal-Lux-Blason, We are also known as “Soft-in-the-Head” (although our head is as hard as yours; We know this having tested it again and again against the Bughouse walls, walls of mortared brick).

We, also known as the “the Lunatic,” are the author of unique scholarly works, including “Domesticity as Universal Error,” “Cosmic Disorder and the Ordered Domicile,” “Delirium as System,” “The Inspired Integument,” “Birth: A Questionable Event,” “The Ideal Uses of the Trochus: An Architectural Manifest,” “Reflections on the Fall of Man, the Flood, God’s Wrath and an Inventive Solution”; author of an ongoing inquiry into the similarities between the Turritella, the mazurka, the tongue of the anteater, the corkscrew, the soup mill; author of an infinite set of pamphlets, including “Architectural Indications of the Inner Ear,” “The Anti-Gravity Domicile,” “The Submersible Domicile,” “The Quasi-Perpetual Environment,” and “An Inquiry into the Structural Limits of Time.” (All these fascicles are printed on dove gray Arches and may be had from us for the price of postage.)

If the brain, as We believe, is shaped by thoughts and not the other way around, then our own is composed of one nacreous coil, our thoughts sweeping upward under the influence of a lucent tide, the whole protected by a layering of scales. It is evident that as long as We are living, this supposition cannot be demonstrated. The Memoir, in this instance, must be read as our testament: We wish our skull’s contents to be scrutinized by Dr. Aromal with delicacy and exemplary gravity. After, the brain is to be placed in a canopic jar and given to our mother. It is our hope that, should the brain be of ideal conformation, Dr. Aromal will oversee a lithographic series, printed on Arches and prefaced by Aromal’s inquiry and our brief paper: “The Brain as the Blueprint of a Transcendent Architecture.”

There is no doubt in our mind that it was Père’s description of the assassination of the sea tortoise that so addled us initially. The tortoise, its legs caught in a noose, wheels about the boat as gulls circle overhead shrilly piping. When the tortoise is exhausted, a boy (or several, depending on the turtle’s size) dives into the water and, seizing it, rolls it into the boat, where it is stunned with a hammer and kept helpless on its back.

Already a fire is smoking up the beach. Hauled to shore, the tortoise is thrust into a pit where, thrashing, he is roasted alive under a heap of burning embers. Père insisted on the quality of the meat—especially the flesh beneath the breastplate. He made this joke: “The tortoise carries his stewpot and coffin on his back. He is called tortoise,” Père continued, “because he twists about as he bakes.”

We were perhaps five at the time and found the tale odious; that a creature could be cooked alive in its own shell seemed especially wicked. We were devastated by the realization that living things were killed to be cooked and eaten, that the ribs of the lamb served as a rack for the meat. “It is the leg bone,” Père joked as he carved the Sunday roast, “that gives the dish its shape.” Pitiless Père! As he described the turtle feast on the beach, We squirmed on his lap and looked helplessly on as Death entered the room and the parlor was metamorphosed into a furnished tomb. The turtle’s anguish, the disgrace of its end, gyred in our little head. Seeing how frightened We were, how agitated, how pale, Père held us fast and insisted on describing a market on the Madagascar coast where one may see, set out on their backs on large tables, living turtles cut from their shells and lying in pools of blood. This blood is scooped up by female butchers (also intimately described; Père had never forgotten the ladies of Madagascar) and sold to clients who, having brought their own bowls, drink the fresh blood then and there. Hearing this We began to squeal but still Père was not done; to tell the truth he had only just begun. (Where was Mère? In the kitchen overseeing the jam-making. This story takes place in berry season.)

Turtle meat is—as you have ascertained—prized in Madagascar, and now that the turtle is free of its shell and bellowing, a steak is cut from its breast and then another; the entrails sliced away, the feet sold next and the liver. Soon all that remains are its lungs, heart, and head. O horror! The turtle’s eyes are still blinking, its beak opening and closing. And as if this were not enough to keep a child from sleeping for the rest of his days, Père now recalled the head of a decapitated prisoner he had seen when he was himself a little boy, rolling onto a cobbled courtyard before being picked up and dropped into a basket. “Its eyes were open wide,” Père said, “and its lips were flecked with foam. Had it been able to speak, it would have cursed the day of its birth.”

Despite his firm grasp, We leapt from Père’s knees as though they were red-hot and We hit the ceiling, screaming. This was the first time We blew our stack, and Mère came running with her spoon, her lips sticky with jam. We were on the carpet now, spinning like a top. Père gave us a terrific kick to shut us up and We—reduced to a quivering jelly—were hauled off to our room by Père—thundering like Jehovah, Mère behind weeping, her spoon in the air like a wand, the cook after, and last of all our nurse sniveling into her skirts. As soon as We reached the nursery, We threw ourself under the bed and refused to budge; anyone who attempted to pull us out was bitten. Père insisted We be “let to rot.”

It was there, under the bed in the nursery, that little by little We recovered from nervous exhaustion and began to dream of impervious integuments; it was there that our thoughts began to spin like the revolutions of an axle box, preparing the way for our ultimate discovery: the Domicile as Time-Absorbing Cuticle.

Because We proved incapable of formal schooling, We were tutored in the nursery by Monsieur Tardy-Cul, who, whenever We proved testy, warned us that Père had threatened to boil us like a soup bone and who made us wear a heavy wool bonnet with ears even in August, causing our brain to quicken vertiginously and deepening the condition Dr. Aromal diagnosed as delirious, brought on by our terror of being devoured by the man the natives of Madagascar called the Meat Grinder. (At this stage, fearing that Père might poison our porridge, We insisted on a food taster, having learned about them in our expurgated Arabian Nights, which Tardy-Cul read with an ill-tempered lisp. We also asked for a bodyguard, for We feared if he could not manage to poison us, Père would come upon us as We slept to crush our kidneys with a hammer, or—should he be unable to break the door—send a cobra down the nursery chimney.) We lived in constant fear that at any moment Père would seize us, tear us apart, shove us into his monstrous mouth, grind us to a pulp, swallow us, digest us, and shit us into our very own chamber pot. (We now know that in his accelerating decrepitude Père had forgotten us entirely, consumed by the memories of his exploits in Madagascar: sexual, military, and gastronomic.) The more We were degraded by our tutor and his threats, the greater did Père grow in our mind. Soon there was not an inch in which Père did not crouch fully armed with kitchen knife, cooking pot, and Appetite.

After an epileptic crisis caused by Tardy-Cul’s tale of Bruce in Ethiopia who, when looking for the source of the Nile, stood by aghast as sirloins were cut from living cows and eaten raw and fuming, We were rid of Tardy-Cul forever, and all manner of Tardy-Culs thereafter; and, following a minor upset over a governess’s tortoiseshell comb, allowed to school ourselves in the tranquil cove of Mère’s chamber as she knitted mufflers for the poor and prayed for our health, and where We learned the niceties of class systems, domestic gardens, the names of the colonies, their imports and exports, and, by drawing up lists, to write in a gorgeous hand:

One afternoon Mère told us a charming little anecdote that was to be the key to our vision which has ceaselessly inspired us and which prepared us for what was to follow: the visit of Madame Roseveine de la Roulette. Mère told Madame de la Roulette’s own story about a hermit crab who, having outgrown his own shell, found an ivory pipe washed to shore and, trying it on for size, took it for domicile. From then on the crab could be seen making its way along the beach, a scrap of seaweed clinging to the stem like a flag. The story made us laugh until We wept; Mère and We made merry deep into the afternoon.

All things of importance have a tendency to inscribe themselves on the sensile pages of our vivid histories. One glorious morning Père was trundled off to Angers to be treated for phlebitis, colitis, laryngitis, and gouty arthritis. As he was not expected to return before evening, Madame de la Roulette was invited for a morning’s visit. Because Père hated her for some reason, We were sworn to silence, delighting in a secret with both Mère and the maid, who was very gay and winked whenever she caught our eye, quivering with laughter like a greased eel. All this created an atmosphere of expectation so that the morning of the Great Adventure, and even before it began, We invented what We came to call our Dreamful Architecture. With colored pencils We sketched three worldly domiciles in which We could imagine dwelling in safety and peace.

That morning We imagined a summer domicile of sweet grasses, sprinkled with good earth and watered daily. This domicile is cooled by the natural process of evaporation, a process demonstrated to us by Tardy-Cul and which until that moment We had deemed of no interest whatsoever. By summer’s end this domicile could be harvested. It came to us to suggest to Heads of State that such dwellings be manufactured en masse for the rustics of tropical climes.

We next imagined a spherical domicile of padded India rubber so buoyant it could travel the rivers of the world sans dommage aucune; for example, its front portal snugly shut, this domicile could navigate waterfalls and rapids without taking in water.

And We invented an airborne domicile with an inflatable roof made of a balloon in the shape of a gently convex mattress that would both keep the domicile pleasantly shaded and protected from the rain, as well as provide nesting places for birds. This domicile looks like a low-flying cloud and its inhabitants dwell far from inquisitous and nefarious eyes. It may be anchored above rain forests and so serve as a platform from which to discover the leafy theater below—animated by birds and butterflies and men: agile tribes who leap from tree to tree with their babes and their pantries strapped to their backs.

At eleven o’clock, Roseveine de la Roulette came to visit, bringing with her a charming collection of shells kept in a large box fitted with drawers. This was carried from her carriage to the summer porch by our man Lagrange. Throughout refreshments We eyed the cabinet with curiosity until, having delicately licked the sugar from her lips, her bodice quivering under the impulse of satisfied gourmandise, Roseveine took my hand in hers and led me to the mysterious object of my desire. With soft fingers she pulled the first drawer open and revealed a collection of Turbo shells, “stalwart bodies,” said she, “that cannot be torn from the rocks, not even by the strongest hands, nor in the roughest weather.” Lifting out a full-bellied, canary yellow specimen, she dropped it in our lap, where it appeared to melt like a knob of butter. She next took up a gold-mouthed Turbo; its interior was the color of egg yolk. That morning We were allowed to hold in both our trembling hands a Turbo marbled green, its nacre shining like the white of a young and healthy eye; a green Imperial parrot Turbo from the China seas; and a violently violet Turbo from New Zealand. Already flushed with excitement, We nearly wept when, the shells returned to their cabinet, Roseveine, her little nails glistening like an intimate nacre, opened a second drawer and initiated us into another world of wonders: spurred Imperators studded with spines, a Delphinula sphaerula as tusked as a tribe of elephants, a tiny trellised sundial from the coastal seas of Tranquebar.

The morning was spelled by Turritella—so like the horns of unicorns—a fantastical harvest of spotted cowries brooding in their cotton wool like the eggs of dragons. The day proved mild, the sun filtered by the lime trees, the air palpable with the sound of bees and Roseveine’s silvery laughter. When she was not handing us a shell, she was proffering bonbons in silver paper and although We were but six, we shuddered with rapture, thinking how wonderful it was to share the world with women!

Mère had lunch brought to the porch and because We were so well behaved and Père hours away, his thoughts far from us and ours from him, We were allowed to stay, to continue to hold the shells Roseveine proffered one by one. Enraptured We listened as she, caressing our curls, described the eyes of the cuttlefish “like brown silk shot with threads of gold”; told how she wrote all her correspondence in an ink found in the ink bags of fossil cuttlefish and sent to her from Oxford, England, by a natural historian who wrote books under the pseudonym Aster O’Phyton. This ink needed only to be reduced to a powder and mixed with water to produce a sepia of the best quality. What had precipitated such instantaneous death and fossilization that the ink sacs had not ruptured or rotted? We wished such a calamity upon Pére. How We should have loved to see him reduced to stone! And when Roseveine described the kraken, its arms the size of mizzenmasts, its suckers the size of pot lids, raking sailors from ships and shell collectors from the coastal rocks, again We imagined Pere’s instantaneous ruin. However, such revengeful thoughts caused us pain. It was impossible for the Butcher of Madagascar to fall in pieces at our feet: those pieces would reanimate and flourish! Instead of one, a thousand thousand would surge forth and more: a Butcher for each second of the day! For a moment the sky darkened; I heard a beak snapping in the air, a beak studded with an infinite set of teeth. But then Roseveine took up a pearl. It sparkled in her palm like a tiny, pristine world and caused us to smile once again.

Before she left, Roseveine gave us a Voluta imperialis so monumental, so sturdy We declared We should very much like to live in it. For at once We intuited: Within such a chamber We might forget that moments are extinguished as they happen, that Time is a famished mouth crushing everything that falls into it (and sooner or later everything falls into it!). Already We dreamed of drifting within the smooth coils of a boy-sized shell, of distilling nacre from the blood-soaked air of the paternal Domicile, of living and sleeping in a shallow, navigable room, and of marrying the transmarine Roseveine. We proposed right away and she, bubbly with laughter, drew us to her bosom and kissing our ear murmured: “Sweetheart, I am old enough to be your mother!” (I believe she was but twenty-five at the time.) Her smell of ambergris was new to me and our infant birdling rose for one thrilling instant and briefly piped—for what exactly? We could not have told you.

That night, and once We were adrift in our little bed, a bed in the shape of a scallop, and, thanks to a tantrum, suspended from the ceiling so that it could be reached only by a rope ladder, Roseveine’s green turban, her horned Murex and shimmering Tritons, her true labyrinths and false cornucopias, swiftly, silently orbiting in our mind’s eye, We began to dream our Dreamful Architecture of Unfulfilled Desire, which, in time, evolved into the Ideal Architecture of Fulfilled Desire: the prodigious marriage of aesthetics, chemistry, and psychiatry. As snug as a cephalopod in its retreat, our ladder coiled at our feet, We began to seriously investigate the Domicile as a Sanctuary in which to float far from the blustering winds of patriarchy, the sounds of bells, of kitchen chatter, the horrible ring of the telephone recently installed.

The Voluta pressed to our lips, the words We had heard for the first time tumbled about in our brain like bits of green glass at the bottom of the sea: coral zone, coralline, littoral; annelids, ammonites, and zoophytes . . . Yes, these lovely words and also certain phrases she had whispered into our eager ear such as obscure crevices and lonely places; deep waters, the sand under stones; muddy bottoms, the Sea of Aral, stalk-eyed crustacea, gardens in penumbra, rafts of tropical debris; the herring fleet at Wick Bay, tiger cowrie . . .

We were roused in the middle of the night by Père who in his pain and fever imagined himself in the thick of the wars in which he was such a devastating player; the years in Madagascar when from Majunga to Tananarive, the roots of trees were gorged with blood and all the earth blackened by the dead. His pain was great; he could not move his bloated legs but only thrash his arms and hack at the air with his sword and shout: “I am the Kingdom and the Glory!” We could not help but hear him and, plunging beneath the covers, weep. It came to us that the world is far too corrupt to have given occasion to the gentle mollusk, and imagined it an asteroid fallen from some other universe.

Because of Père’s incapacity—he kept to his bed as though fixed there with glue—Mère invited Roseveine to luncheon the following week. Père, propped up with pillows, was polishing the pistols that had served him in the wars, all the while shouting at phantom whores and soldiers. From time to time his voice floated out to the porch where We sat in the shade of the lindens served by the maid nearly doubled over with suppressed laughter. Indeed it seemed a daring thing to be making merry on the porch with a woman whose company Père had forbidden, whilst Père, confined to his chamber, engaged in phantasmagorical fornication and war.

We were served an ethereal lunch: a salad of nasturtiums, squash blossoms made into beignets, an orange-flavored flan—the whole washed down with rare Chinese tea. Whenever Père’s ranting would reach us, Roseveine bubbled over with laughter. On one of these occasions We took the liberty to slip from our chair and, concealed by the tablecloth, to take one of Roseveine’s slippered feet in our hands.

“And what are you up to, little husband?” said she, gently teasing. “Playing at cobbler?”

“Yes!” We replied, although it was a lie. “That is what We are doing. We are playing at cobbler!”

“A royal cobbler, apparently,” she said laughing to our mother, “who refers to himself with a royal We! But I would have it no other way,” said she. “In other words, if I am to be cobbled, well then: cobble me royally!”

Reassured by this, We unlaced the slipper to find a little stockinged foot, deliciously damp, smelling of live oysters and raw silk. With trembling lips We caressed her toes. We heard Roseveine sigh. With a tinkle her custard spoon fell to its dish.

“The flan is delicious,” Roseveine said to our mother, “and so is your little son.” Bending over and peering down under the table she smiled at me meltingly and with her hand caressed my cheek. For one dizzying instant she probed my ear with her little finger. “Your ear is exactly like a Bulla ampulla,” said she.

So touched were We our eyes welled with tears. “Little husband!” cried Roseveine as We nibbled her instep, “I have fallen in love and decided to divorce Monsieur de la Roulette and—with your mother’s permission—marry”you!„

We grabbed her calves, and our face pressed to her knees, clung there like a modest echinoderm sans the instinct to travel. For a long moment We stayed there, our thumbs pressed to the rotator bones of her ankles.

But this charmed moment was interrupted by a roar from Père, the shrill voice of Père’s nurse, a seismic thudding that seemed endless and held us frozen in terror and surprise, and then the sudden appearance of Père himself seething with rage and nearly busting from his bathrobe and Moroccan slippers. Anchored to the doorframe and with all the strength he could muster, Père, visibly approaching exhaustion, bellowed:

“What is that Jewess doing here?”

Again Roseveine’s laughter percolated through the air. Standing to face him, she gathered her skirts to her bosom and spreading her legs pissed profusely, her amber water a stunning spectacle recalling the engravings We had seen of the Victoria Falls on the Zambezi and Tisisat on the Blue Nile. Not surprisingly, her piss had the smoky fragrance of Lapsang souchong. This sublimely anarchic act hurtled Père into the vortex of apoplexy; he did not survive the afternoon.

But this she could not know. For as Père, brittle as mummy, crumbled to his knees, his hands splashing in the steaming puddle she had made, Roseveine sailed off and away, down the balcony steps, into the garden, past the stone fountain, the banks of trees, into the pergola and out the garden gate. She created a void that has never been filled, not even by the persistent memory of her laughter.

Several months after Père’s demise, Roseveine came to visit one last time. She and her husband were about to leave France for French Canada, where they intended to form a publishing company devoted to the Natural Sciences. Their first publication would be Aster O’Phyton’s Ocean illustrated with lithographs, some of which she had brought along to show me: A Fleet of Medusae, Tubipora Musica, and one which caused us to cry out in terror but also in secret delight: A French Officer Seized by a Gigantic Cuttlefish