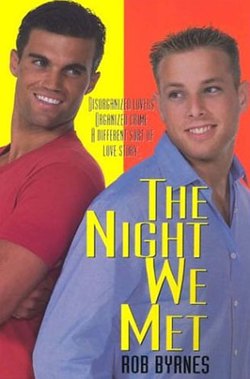

Читать книгу The Night We Met - Rob Byrnes - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 Life Before Frank…

And Why I Particularly Hate Nicholas Hafner

ОглавлениеThe first thing you should know is that I’m a romantic. I’ve tried to become another jaded, cynical New Yorker, but I’ve failed. Yes, I live in the real world and have all the problems that come with it, but that’s never seemed to dampen the visions of romance that live in my head, where Bogie and Bergman always have Paris, Fred and Ginger sweep across my cerebellum, and, if I’m not dating Mr. Right, he’s waiting around the corner, just as the cliché promises.

And I like the trappings of romance: cards and flowers; champagne and strawberries; long walks with a lover on warm beaches under blue, cloudless skies as our Golden Lab romps in the surf…Reality has tried but failed to beat the saccharine out of me. Those illusions of romance live deep inside me.

The second thing you should know is that Webster’s offers several definitions of the word romantic, including “having no basis in fact,” which is sort of the yin to the yang of passionate love. But that’s an easy definition to overlook when Fred and Ginger are distracting you.

And I’ve had my share of distractions. Take Ted Langhorne, for example.

I had already lived in Manhattan for fifteen years before I met Ted, after moving from Allentown, Pennsylvania, to realize my dreams of going to New York University, finding a pack of cool homosexual friends to run with, and becoming one of the preeminent literary voices of my generation.

Of course, those were dreams. In reality, I did manage to graduate from NYU, and I did manage to befriend a number of homosexuals, although no one who was known far and wide as “cool.” But the closest I came to becoming the literary voice of my generation was when my bosses at Palmer/Midkiff/Carlyle Publishing, Inc., let me dip into the slush pile—that’s what we in the business call the heaps of unsolicited and largely unreadable manuscripts that arrive in our offices, day in and day out—to see if I could find the literary needle in the haystack that would launch me as the Maxwell Perkins of the 1990s. That needle didn’t exist, of course, because if it did, someone else with more ambition and a sharper eye for talent would have found it long before I did. But still, I could dream…

And then came Ted.

Ted was an accountant, and he acted like I expected an accountant to act, which doesn’t mean that he was boring, but…Well, let’s just say that he was more adult than any of my other friends. More mature. More…well, yes, boring; but boring in a good way. And after fifteen years in New York City—years that spanned the end of my teens, all of my twenties, my early thirties, Reagan and Clinton, AIDS and Mad Cow Disease, disco and house music, cocaine and Ecstasy, and about eighty-nine managers of the New York Yankees—I was ready for boring in a good way.

And, of course, we met cute.

“Hey,” he said, approaching me as I stood alone, back to the wall of a Greenwich Village bar late one Friday night. “Aren’t you a friend of John’s?”

“I know a lot of Johns,” I replied dryly.

“I thought so,” he said and flashed a dazzling, inviting smile. “Can I buy you a beer?”

Okay, I know…not exactly Love Story. But, since it did work out at the time, it still sort of counts as a romantic, love-at-first-sight kind of meeting. In my mind, at least.

He was tall and handsome, thick chestnut brown hair framing a wholesome face that belied his true age, which I later learned was forty. I didn’t have to touch him to know his body was taut and muscular, although I discreetly did, anyway. And those eyes—piercing green, flecked with brown. I instinctively knew their color, even though I defy anyone to ascertain the color of someone’s eyes in a dimly lit bar.

“I love your eyes,” I told him a few beers later.

“Contacts,” he replied.

In retrospect, I know that was the moment I should have run away. That was the moment when Ted Langhorne had first shown me his basic lack of understanding of the illusions of romance. That was the moment when Ted Langhorne had revealed that deep inside the soul of this accountant was…another accountant.

But the moment passed. For those of us who still believe in the illusions of romance, they always do.

That night we went back to his apartment in Chelsea. He showed me his view—the apartment building across the street—and, after some idle conversation, he showed me that taut and muscular body. I put it to good use.

“So, what do you do?” he asked later as we lay entwined on his bed.

“Editorial assistant at Palmer/Midkiff/Carlyle. Ever hear of them?”

He hadn’t. Given PMC’s relatively small size in the era of increasingly large publishing houses, that wasn’t especially surprising.

“It doesn’t matter. It’s probably time for me to move on with my life. I’m not getting anywhere.”

“Is that what you want to do for a career?”

“No,” I confessed, a bit embarrassed, because he was about to become one of the few people in the world to know my dream. “I want to be a writer. But…no luck so far.”

“Why?”

“Writer’s block. A decade’s worth of writer’s block.”

Ted persisted, and I finally confessed to ninety-seven pages of an uncompleted semiautobiographical manuscript about a young man’s coming of age in Allentown hidden in a desk drawer back at my apartment.

He said he wanted to read it.

“You don’t have to do that,” I said. “I’ll have sex with you again even if you don’t read it.”

And I did. But late the next morning, while we were still in bed wrapped in each other’s arms, my hand gently caressing his broad, smooth chest, he asked, “So, when do I get to read your novel?”

“Are you serious?”

“Yeah. I want to read it. You said that it’s semiautobiographical, right? Well, I want to see what you’re all about.”

And if I was already starting to fall in love, that pushed me over the edge.

Ted, too, seemed to accept the inevitability of our relationship. We’d only known each other for hours, but we both seemed to instinctively know we were meant to be together forever.

We didn’t need to discuss whether or not he’d follow me home the next morning. Of course he did. Together Forever had its roots in Together the Next Day, after all, so there’d been no question about it.

We took the subway to West Eighty-sixth Street, then walked the short block to Amsterdam Avenue, where my bland building anchored one corner of the intersection. We passed under a weathered green canopy jutting from the grimy brick facade and entered the lobby. The elderly doorman nodded vacantly as we passed.

“Top-notch security here, huh?” said Ted as we walked into the tiny elevator.

I pushed the button for my floor. “Nothing but the best for me.”

We reached the seventh floor and I ushered him into my apartment, slightly embarrassed when I realized I’d left newspapers and dirty laundry strewn throughout the room that served jointly as living room, dining room, and, for the most part, kitchen.

“Sorry for the mess,” I apologized, hurriedly collecting an armful of the previous week’s discarded clothes from the faded couch angled in the middle of the room. I opened the door to the bed-sized bedroom and tossed them out of sight.

“Nice place,” he said, looking around and choosing to ignore the disarrayed bookshelves, fraying furniture, dying plants, and worn hardwood floors. “A little cramped, but livable. Which is more than you can say for most apartments in Manhattan.”

I hunted through the refrigerator for a couple of Cokes. “I used to have an apartment in the Village, but I got tired of living in a rabbit warren. This place might be small, but it’s a palace compared to that place.”

“There are just too many people in this city,” he called back.

When I returned with the Cokes, Ted was gazing out the window.

“Not much of a view, I’m afraid,” I said.

“One of the paradoxes of living in New York City. There are a lot of great views, but you need a lot of money to get one. The rest of us get to look at other apartment buildings.”

I handed him his Coke. “Sometimes you sound like you don’t like it here.”

“I survive. But one of these days, Iowa, here I come.”

“Iowa?”

“Or Ohio…Utah…”

“Why?” I asked. “Do you want to get back to the land? Or do you just want to live in a state with four letters?”

He smiled and waited for a blaring car horn to stop. “I wouldn’t mind a little peace and quiet in my life.”

“But you can’t leave New York,” I told him. “I don’t think there are any gay people in Iowa.”

Still framed in the window, Ted leaned forward slightly. “I can see the entrance to your subway station down on Broadway.”

“Really?” I already knew that and didn’t care, but I used it as an excuse to press up against him in the window.

He felt my body rub against his and turned slightly to kiss me. When he did, his striking green eyes—and, to me, they would always be his eyes, not his contact lenses—narrowed to slits, and he moaned softly.

We stood there, framed in the window, for several long minutes.

“I think you’ve got something to show me,” he finally said softly.

“Mmm-hmmm,” I purred. I took a step back and, in one swift and very practiced motion, unsnapped my top button, unzipped my fly, and slid down my briefs. My semierection spilled out.

He laughed. “That isn’t exactly what I meant. I was talking about your book.”

“Oh…” I said, embarrassed.

“But…” He trailed off as his mouth moved down my torso. “This is good, too.”

Half an hour later we were both sprawled on the couch, naked, sweaty, and more than a little sticky. That’s when he said, “Now, about that book…”

Without disentangling myself from him, I blindly reached behind me and patted my hand around until I felt my desk. Then, still operating through sense of touch, I moved my hand around until I felt a drawer handle, slid it open, and pulled out the too-thin manila envelope.

“Voilà,” I said. “Allentown Blues, Chapters one through seven. And please don’t laugh at me.”

Ted took the envelope from me and slid the ninety-seven neatly printed pages of manuscript out of it—along with the title page, which simply read “Allentown Blues by Andrew Westlake”—before tossing the envelope to the floor. Then he started reading.

He was on page twelve or so when I felt myself starting to nod off. I decided to let myself go, exhausted from our lovemaking, and delighted my body was entwined with his. And when I woke up, he was done.

“So?” I craned my neck to see his face. “What did you think?”

He smiled. “Why don’t you finish it?”

“First, tell me what you think.”

He started stroking my hair. “Well, it’s very funny. I love your dialogue.”

“Uh-oh. I feel a ‘but’ coming on.”

“The only ‘but’ is that you left me hanging. I want to know what happens to Grant. Does he come out of the closet in Allentown? Does he escape to New York?”

“I don’t know,” I answered truthfully. “Grant hasn’t decided yet.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that, when I started writing, I had everything plotted out. But the more I wrote, the more the characters started taking on lives of their own. That’s why I put the book away. I don’t know what should happen next. They haven’t decided.”

“I don’t get it,” he said with a self-conscious laugh. “Maybe I don’t understand how the creative mind works.”

There. I had a second warning. I had another chance to run away, screaming. Sure, he was intelligent and beautiful and sexy and gave a great blow job. But he didn’t understand the illusions of romance and he didn’t understand why I couldn’t just force my literary creations to follow a one-dimensional plot outline.

But, like the first warning, I ignored it. Just as I would ignore all the subsequent warnings. Hundreds of them.

Intellectually, of course, I knew I was in love. But the intensity of the emotion caught me by surprise. I realized that I was beginning to formulate my thoughts using a “What would Ted do?” construct, and his verbal distinctions found their way into my words. Some days, I would catch myself staring into the cracked bathroom mirror, wondering what there was about the person staring back that an incredibly beautiful and fascinating man like Ted could possibly find to love.

I forced myself to confess that, yes, I was a good-looking man. The wear and tear I had put on my body hadn’t caught up with it yet. I still had a full head of naturally brown hair with occasional golden highlights, and my skin still had a healthy glow, although admittedly, Oil of Olay played its part. Good fortune and good genetics had provided me with a healthy physique while sparing me the rigors of the gym.

But still, I was no Ted.

Ted’s love should have made me feel good about myself, but instead it consumed me in self-doubt. I felt unworthy of his attention and affection.

That irony didn’t escape me.

I got over it. Mostly.

Three months later, when his lease was up, Ted moved into my apartment on the Upper West Side at Eighty-sixth and Amsterdam, which consequently became a lot more cramped. But I didn’t mind, because I was in love and we were acting out the ritual of domestic bliss.

Six days after Ted moved in, I presented him with a carefully wrapped final draft of the manuscript for Allentown Blues.

“You did it!”

“I did it,” I replied, quite proud of myself and thrilled I’d made him proud of me. “Grant finally told me what he wanted to do with his life.”

“And what’s that?”

My finger softly traced a line from his forehead down the bridge of his nose. “He decided to move to Manhattan and meet a nice accountant.”

On the following Monday, I walked into the offices of David R. Carlyle IV, who was the black sheep son of David R. Carlyle III, who was one of the founders of Palmer/Midkiff/Carlyle. That was enough to keep him in a lot of money and entitle him to the position of senior editor, which in David’s case was more or less a part-time position.

Although he was quite a bit older, David was the closest thing I had to a social acquaintance at PMC for many of the same reasons that he was the black sheep of his family. He was unapologetically—sometimes flamboyantly—gay, he loved to spend money, and he often acted as if he considered PMC little more than a place to hang out between parties and pick up a paycheck.

In short, he was my kind of guy…but with more money. A lot more money.

“Andrew,” he gushed when he saw me. His wide, pink face broke into a smile. “Good to see you. And how are things with you and your accountant? Ted, isn’t it?”

“I’m in love,” I replied without thinking twice.

“Good for you.” He fussed around his office. “God, look at this place. Dust an inch thick. And nobody’s been watering my plants.”

“Can’t get good help nowadays.”

“Don’t I know it,” he said before he brightened and added conspiratorially, “Well, that’s not totally true. I met the cutest young thing the other night. I think he’d make an excellent house boy.”

“Can he dust?” I asked, raising an eyebrow.

He threw his hands in the air with a dramatic flourish. “Perish the thought! I certainly wouldn’t want him to get dirty.” He fussed some more and motioned for me to take a seat. “So, what can I do for you? Have you finally had it with PMC? Are you here to tell me you’re quitting?”

“Of course not.”

“God, I wish I could,” he snapped. “But I suppose it’s good for me to have a place to go that gets me off the streets for a few hours every week. So…if you’re not quitting, and I know you’re not here to do something foolish like ask for a raise, what can I do for you?”

Without a word, I handed him my manuscript. He took it from me as if it were breakable and glanced at the title page.

“‘Allentown Blues by Andrew Westlake,’” he read, settling his overstuffed frame into an overstuffed chair. Then he glanced up and jokingly asked, “Any relation?”

“I thought I’d give PMC the first crack at it.”

“Why not? Our slush pile is as good as anyone else’s.” He slipped me a quick and somewhat indulgent smile. “I’ll read it myself, Andrew. But”—and now his voice slid into a deeper octave, which was, I presumed, supposed to connote professionalism—“I hope you understand that we can’t publish it just because you work here.”

“I understand.”

“Good.”

“But remember,” I said, as I rose to leave, “I know where you live.”

One week later, just as I was reaching the point where I thought I was going to be rejected, David Carlyle called me.

“I’m sorry it took me so long to finish your book,” he said, “but I took it with me to Fire Island and I didn’t have as much free time as I’d expected. Please don’t ask me about that lovely German boy who was dominating my time.”

“So, what’s the verdict?” I asked, hoping to bypass a self-indulgent soft-core account of his week in Cherry Grove.

“You’re on. I thought it was delightful. A little light, but delightful.”

“Light?”

“When PMC has published novels in the gay genre in the past, we’ve tried to look for things with poignancy. I loved Allentown Blues, but I wouldn’t exactly call it poignant. It’s just a fun read.”

“Actually,” I said defensively, “I think there were some poignant parts in the book.”

“Whatever,” he said, not particularly caring what I thought was in my novel. “I’ve already talked to some of the other senior editors—you know, the ones who have the same title as I do but with the authority to actually do something around here—and I’ve convinced them that we should publish it. We’ll let the readers decide if they think it’s appropriately poignant or not.”

Ten months later, Allentown Blues was in the bookstores.

Well, not all the bookstores. It was in gay bookstores, and one or two copies sometimes found their way into the Barnes & Noble superstore on Upper Broadway, but I suspect that’s mostly because Ted and I made periodic anonymous calls to ask if they had it in stock.

The $7500 advance I received from PMC—the only money I made off Allentown Blues, by the way—paid for a one-week vacation for two in Key West and reduced a few credit card balances. And then it was back to the day-to-day drudgery of life in Manhattan.

Time seemed to pass at an alarming rate. One night I met Ted, the next night we had moved in together, the next night my book was published, the next night we were in Key West, the next night we were celebrating our first anniversary, the next night we were in a mall in Jersey City and I decided that I’d show Ted the new art book I’d helped edit and…

“Let’s go,” he said abruptly, grabbing my arm and pulling me toward the front of the store.

“What’s the matter?” I asked, returning the book to the shelf.

“Nothing. I just want to go.”

He dragged me to Sears—such a Ted store—and pretended to look at stereo equipment.

“So, what was that all about?” I asked. “Does Waldenbooks bring back some repressed childhood memories or something?”

“No,” he said unconvincingly. “I just wanted to leave.”

“Okay. Fine.” I joined him in pretending to look at stereo equipment for a few minutes, then told him I had to find the rest room. When I was out of sight, I backtracked and took the escalator down to the lower level.

Back at Waldenbooks, I found the spot in the store that had troubled Ted. I didn’t see anything. All that was there was…

…the discount bin.

With about ten copies of Allentown Blues, all bearing a huge Waldenbooks label that told the world that this book that PMC had published just a few short months earlier, with a retail price of $23, could now be theirs for only $2.95.

“No,” I gasped.

A middle-aged woman who’d been scanning a copy of the dust jacket, trying to decide if my novel was worth her $2.95, glanced at me. Then she glanced at my picture on the dust jacket, then back at my face, trying to tell if the pitiful failed author of this discounted book could possibly be the same pitifully moaning customer standing next to her in a mall in Jersey City.

“I’m sorry,” said Ted, who was suddenly behind me. Oblivious to the fact that we were in a Waldenbooks in Jersey City, he wrapped a muscular arm protectively and lovingly around my chest. “I didn’t want you to see this.”

“I’m a failure,” I said.

“Don’t say that. All those people who didn’t buy your book are the ones who lost out.”

“I love you. You say the nicest things.”

The middle-aged woman, for some reason unfazed by our affection, held the book open to my photograph on the dust jacket and asked, “Is this you?”

“No,” I said and walked away.

We had dinner at the food court.

“I’m a failure,” I said again.

“So, what are you gonna do about it?”

I drew little designs in ketchup with a french fry, trying to decide what I was going to do about it. “I guess I’ll just resign myself to the fact that I’m not a writer. I am and will always be a slave boy at PMC.”

“I’ve got a better idea. Why don’t you write another novel?”

“No way. It’s too much work to go through just for humiliation.”

And suddenly that middle-aged woman from Waldenbooks was there. “I knew it was you,” she said too loudly. A few other food court patrons turned to see what was going on. “You’re Andrew Westlake!”

“Yes,” I confessed.

“I’m sorry about bothering you at the bookstore,” she said, still too loudly and without bothering to apologize for bothering me at the food court. “It’s just that I never met a real author before.” She opened her Waldenbooks bag and produced her marked-down copy of Allentown Blues. “Would you autograph this for me?”

Three teenage girls sitting at a neighboring table with several plates of the food court version of Chinese took note.

“You write a book, mister?” one asked.

The middle-aged woman proudly held up her copy of Allentown Blues for the girls—and several other patrons—to see. “He wrote this.” Then she flipped to the dust jacket photograph and said, “See? That’s him. That’s Andrew Westlake.”

“Cool,” said one of the girls.

The woman set the book down again and told me her name, so I wrote, To Marlene Birrell…Suddenly, you’re my number-one fan! Enjoy the book! Best wishes, Andrew Westlake.

We took the train back to Manhattan, then another one back to the Upper West Side, but it wasn’t until we walked through the front door that Ted said, “So, when are you going to start your next novel?”

“Oh, please,” I said, dismissing him but at least smiling now.

As he unbuttoned my shirt, he said, “Hey, now you’ve got a real, live fan. If you don’t write another novel, Marlene Birrell will be very disappointed in you.” He stopped, then added, “So will I.”

A few months later, Ted and I were enjoying a Sunday afternoon in late May, lying on a blanket in Central Park.

“Look at them,” I said, watching a young couple squabbling from a distance. “Wouldn’t you like to know their story?”

“Not particularly.”

I rolled over and looked at him. “What’s the matter? You sound distracted.”

He glanced at me, then trained his eyes somewhere else. “I guess I’m just a little tired.”

I tossed a playful punch at his shoulder. “Come on. We’re in Central Park, the people-watching capital of the world. Let’s people-watch!”

“That’s what I’m doing,” he replied dully. “I’m watching people. What else is there to do?”

I scanned the park, found the squabbling couple again, then pointed them out to Ted. “Here, let me show you how to people-watch. It’s an art, and this will help unlock your creative side. Now, you see that man and woman over there, arguing?”

Ted grunted.

“Well, I think she’s just told him she’s pregnant. But he’s only twenty-two, and he doesn’t want to be tied down with a wife and a baby when he’s so young. So now he’s trying to convince her to have an abortion, but she…she…uh…she’s a devout Catholic, so she refuses to do it. And that’s why they’re arguing.”

I turned and looked at Ted. He wasn’t looking at me or the young couple.

“So, what do you think they’re arguing about?” I asked him. “What kind of story can you come up with?”

He turned and finally looked me in the eye. “I think they’re fighting because she’s trying to force him to make up stories about the people they’re watching in the park.”

Some of us, I suppose, are cursed by our delusions of creativity. But some people are cursed by their lack of creativity.

And Ted was one of those people.

My second book was The Brewster Mall, which had a few gay characters—well, it did involve a huge retail shopping complex, after all—but was mostly a humorous story about the intermingled lives and loves at a mall not unlike the one in Jersey City. It even had a Waldenbooks where the philistine manager loaded the discount bins with the works of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

David Carlyle still thought a little more poignancy couldn’t hurt, but—especially since it was mostly about “those drab, colorless little heterosexual people”—it was acceptable and PMC would publish it. I got another $7500 advance.

The dedication read, “To Ted, who made me write this book, so blame him.”

David arranged for me to sign copies of The Brewster Mall at that mall in Jersey City. In the spirit of the book, the Waldenbooks manager set up a discount bin full of marked-down classics.

I sold an entire three copies of The Brewster Mall, including one to Marlene Birrell. Waldenbooks sold out of $1.95 copies of Faulkner and Salinger. And the guy who managed the Arby’s in the food court was pissed off because he thought I’d libeled him. It wasn’t one of my better nights.

It was a long ride back to Manhattan, made bearable only because I knew that when it came to an end, I’d see Ted. And after two years, seven months, and one day, our relationship felt as fresh as ever. I was still very much in love.

I unlocked the apartment door. It was dark inside.

“Ted?” I called out. There was no reply.

I shrugged it off. Outside of tax season, Ted didn’t work late very often. But there were occasional nights. If he had decided to stop somewhere for a beer, who was I to begrudge him?

I tapped the play-back button on the answering machine and listened as I poured myself a stiff drink.

Beep. “Hello, dear, it’s David. Please call me when you get back from New Jersey. I want to make sure you escaped alive and that you’re still wearing natural fibers. Oh, yes, I also want to know if you sold enough books to make my company enough money so I can finally retire and move away from this godawful city. Love you.” Beep.

I sat down on the couch with my scotch and water and called David back. He answered on the first ring.

“Three books?” he said unhappily. “Oh, Andrew…”

“What can I say? They bought Faulkner and Salinger and passed me over.”

“But Faulkner and Salinger are dead, and you were sitting right there. And you’re so stunning, how could they have missed you?”

“Damned if I know. But I have news for you: Salinger’s not dead.”

“He’s not on PMC’s list, so he’s dead to me.”

I laughed, spitting up a trickle of scotch that ran down my chin. “Ah, damn.”

“Excuse me?”

“Sorry,” I said, looking around for a napkin or paper towel. “I dribbled.”

“Well, a day in New Jersey will do that to you,” David said, and he started to launch into some new ideas he had to publicize the book.

In the meantime, I found a paper towel. I was about to wipe my chin when I realized there was writing on it.

Ted’s handwriting.

Written with a felt-tip pen, which had bled into the towel and made the words almost illegible.

And it started: “Dear Andrew…I’m sorry—”

If I strained, I could read it:

Dear Andrew…I’m sorry, but I can’t go on with our relationship. I’ve tried to tell you in person, but you’ve been so busy with your book that we haven’t been able to talk. Again, I’m sorry, but I need more out of life than what we have, and I’ve met someone I think can give me what I feel is missing. I took some of my stuff. Maybe we can talk later. Good luck with your book and your life…Ted.

“Andrew?”

“Huh?” I was still too stunned to react. “I’m sorry, David, I didn’t hear what you were saying.”

“That’s because I haven’t said anything in thirty seconds. I’ve just been sitting here, listening to you whimper. Are you all right?”

“I—I—I don’t know.”

“What’s wrong? You sound horrible.”

“It’s Ted.” I started to feel the haze lifting as the reality of his words sank in. “He’s…he’s…” The tears forced themselves out slowly, and I sank back into the couch.

“Oh, God,” mumbled David, his deeply concerned voice still coming through the phone that was now tucked somewhere near my neck. “Is he all right? He’s not dead, is he?”

“He—he—he left me.” My voice was hollow.

The phone fell to the couch, but I heard David’s distant voice. “I’ll come over.”

A while later, I managed to get off the couch long enough to tell the doorman to let David into the apartment building. I really just wanted to be alone with my grief, but I suppose it was good that he came over, if for no other reason than to finally hang up the phone.

“You’ll be all right,” he assured me in a hushed voice, repeatedly stroking my back as I choked back sobs, curled up in the closest imitation of the fetal position that a thirty-five-year-old man can achieve.

“I loved him,” I moaned between convulsions.

“You’ll get the last laugh when you win the Pulitzer Prize. The men will be beating your door down then.”

Somehow I managed to control myself long enough to turn to him and say, “David, you’re really not making me feel any better about this.”

In the days to come, I found out that what Ted needed more of out of life was packaged in the twenty-three-year-old body of Nicholas Hafner—Nicky to his friends—which meant that I would always consider it a point of honor to call him Nicholas.

Nicholas Hafner was a twink with double-pierced ears who aspired to design windows for a living. He was, at that time, merely an apprentice window designer.

My mortal enemy was an apprentice window designer. No, not just an apprentice window designer—an apprentice window designer who bleached his hair.

Why couldn’t Ted have found himself a nice doctor?

After Ted left, I did a lot of moping. I didn’t leave my apartment for the first week. I spent most of the time sitting perched in the window overlooking Eighty-sixth Street, watching the appropriately gray skies and rain. And sighing. And straining to look toward Broadway to see if his was one of the faces coming out of the subway station, having come to his senses and decided to return home, where he knew I’d forgive him after some brief histrionics.

But, of course, his face never emerged from the subway station. He was gone. He was the property of Nicholas Hafner, the twenty-three-year-old apprentice window designer with double-pierced ears, bleached hair, and absolutely no commitment to anything deeper than keeping ahead of the curve on the latest styles and music. And since I couldn’t really hate Ted, no matter how hard I tried, I came to double-hate Nicholas, even though we’d never met.

If I found any consolation, it was in the knowledge that one day one of them would hurt the other just as Ted had hurt me. Superficial Nicholas would probably discover it was no longer fashionable to shack up with older accountants, and he’d dump Ted for the latest in boyfriend chic. Or Ted would discover that Nicholas—who danced each weekend until five in the morning and was decades away from developing an ability to settle down—wouldn’t and couldn’t offer him the domesticity he craved.

That was my consolation. But when it happened, if it happened, it would be down the road. Right now, Ted and Nicholas were lovers; they were having fun, having sex, and having each other. They were going to dinner parties and clubs and movies. They were living their lives.

I was sighing and sobbing and watching the rain. And the subway entrance.

David Carlyle called me occasionally, but I seldom bothered to pick up the telephone. I hadn’t been going to work, and although David covered for me, as the week wore on and his sympathy waned, he subtly warned me it might be in my best interests to “snap out of it and come back to earth one of these days.” In an effort to lift my spirits, he told me—well, actually, he told my answering machine—that sales of The Brewster Mall were running much better than expected, which I knew was a lie because I’d personally seen how the book was selling and doubted there was more than one Marlene Birrell in the world.

Denise Hanrahan also called. She was probably my closest friend left in New York City, since I’d lost all my other friends when I’d coupled up with Ted and shut out the rest of the world. I usually picked up for her.

Even though Ted had just ripped my heart out and filled the empty cavity with lead, Denise always had a way of besting me in depressing, tragic boyfriend stories. I mean, at least I didn’t consider it a disaster to find out my boyfriend was gay. In a bizarre way, it was almost therapeutic to hear her tales of the horrid heterosexual and allegedly heterosexual men of New York. The Germans call it Schadenfreude—taking pleasure in the pain of another.

And between the passage of time and Denise’s horror stories, I at last reached the point where I was able to leave the apartment. Which was good, because my appetite was coming back and I desperately needed groceries.

My first day out on the street was also the first day in several weeks that the sky cleared, treating New Yorkers to a warm and sunny September afternoon. I spent it walking; walking through the Upper West Side, walking through Central Park…I considered, but rejected, taking the subway down to Greenwich Village; that excursion was squelched because that was where that no-good bastard Ted and his twink boy toy were now living, and I was afraid it would encourage the stalkerlike impulses I was trying to fight back.

It was only when I stopped, after several hours of walking, that I realized I hadn’t seen a thing. I was sleepwalking, that’s all. Exercise for the emotionally dead. And now I was on the east side of Central Park, tired and far from home.

So…

“Andrew! What a pleasant surprise!” said David, after he told his doorman to allow me up to his apartment. “Holding up okay?”

“Well, I’m out of that damned apartment,” I said. “That’s progress.”

David lived in an apartment perched high above Fifth Avenue with a panoramic view of Central Park. You probably know the names of most of his neighbors from the society columns, or People, or at least the Page Six column in the New York Post. On the few occasions I’d been here before, I usually stood slack-jawed, gaping at the grandeur. The wide-open living room, broken up only by a small grouping of chairs, couches, and end tables surrounding an oak entertainment center; the expensive collection of artwork tastefully displayed on the walls; the terrace overlooking the park; the bookshelves lined with dust-free first editions…

But today I was sleepwalking, so I simply slumped on one of his couches and stared at the floor.

Each year, David selected a new color theme and had the apartment completely redecorated. Recently, he’d entered what we at PMC jokingly called—behind his back, of course—his Blue Period. With the exception of the woodwork and the always-polished-but-seldom-played Mason and Hamlin grand piano tucked in one corner of the living room, everything—the walls, the furniture, even the carpet—was a shade of blue.

How appropriate. So was I.

He poured a couple of vodka and tonics. “Well, now that you’re ambulatory again, I hope you’ll be able to join us at Palmer/Midkiff/Carlyle. We’ve missed you.”

“Sorry. But I’m snapping out of it.”

“That’s what you’ve got to keep doing, dear. Keep moving. You know…life goes on, you’ll find someone else, and all those other tired clichés.”

“I guess. But it still hurts.”

“It’s supposed to hurt,” he said, still mixing. “When it stops hurting, you’ll be as emotionally dead as half the other gay men in this town, and you’ll lose your creativity and therefore your livelihood. Then you’ll have to work as a waiter, and the last thing we need in this city is another emotionally dead gay waiter. So let it hurt, Andrew. Let it hurt for me.” He handed me my drink, moved near to me, and almost whispered, “I saw him last night.”

“Ted?” I heard myself ask breathlessly. “Where?”

“Walking. In the Village. Alone.” His voice fell low, and he added, “And he didn’t look happy.”

“Did he look depressed?” I asked with too much eagerness, because if he did, then maybe the affair with Nicholas had already fizzled.

“Uh…not particularly.”

My heart sank. “That’s just the way Ted usually looks. Sort of blank.”

“Yes, but he didn’t look ecstatic!” said David, as if this was proof of something. Which it wasn’t.

“I’m sure he’s had an ecstatic look on his face more than a few times over the past week.” I felt the pain begin to well up again.

David slumped down into a chair, clearly not wanting to probe any deeper into emotional topics that we both knew were basically unavoidable.

In an effort to change the course of the conversation, David asked, “Are you writing again?”

I almost laughed at the silliness of his question. Couldn’t he see that I was totally absorbed in my own misery?

“I haven’t exactly felt creative recently,” I said bitterly. “Who can write with all of this shit going on?”

“Maybe the writing will help you work through it.” Apparently, David was under the assumption that his accidental role in life as the scion of the founder of a publishing empire qualified him as an expert in the therapeutic applications of writing. “And who knows? Maybe this experience will make you a better writer. Maybe it’ll give you more depth.”

“Excuse me?” It sounded to me as if I was getting a little unneeded and unsolicited armchair criticism. “What’s wrong with my depth?”

“Don’t take it the wrong way, Andrew. Don’t be so touchy. I mean, we have had this conversation before. I just thought maybe this Ted thing would…well, you have to admit your style is a little light.”

“It’s supposed to be light. I like writing humorous, enjoyable books. I’m not Ayn Rand.”

“Of course you’re not, dear. People buy her books. Maybe that should tell you something.”

“I’m sorry you’re not happy with my sales. But I don’t know what else I can do.”

“I’m just thinking about you,” David said. “Do you want to be remembered as insubstantial?”

I threw up my hands. “Listen, David, I’m really not in the mood for this conversation. Why don’t we just drop it? You don’t like my books—”

“I didn’t say that!”

“And I’m not in the mood for your criticism. So, let’s just agree to disagree.”

“Fine. All I was trying to do was point out that there could be a positive aspect to Ted leaving you.”

“Let’s drop it,” I said again, regretting my visit.

After we stopped discussing Ted and my writing style, we quickly discovered that we didn’t really have anything to talk about. Not that evening. Every conversation seemed to wind around itself and come back to touch on Ted. The fall social events, vacation plans, the price of lumber in Estonia…Ted managed to work himself into every facet of life.

Falling in love is easy enough. Why does falling out of love have to be so hard?

“You need to find yourself a new man,” said Denise Hanrahan a few weeks later as we killed time over coffee. It was early October, and noticeably colder. “It’s been a month, Drew, and he’s not coming back.”

“Easier said than done. But it seems like all the good men in this city are married or straight.”

“Oh? I hadn’t noticed.”

Denise grimaced at her own remark. It had been bad enough when she’d learned her boyfriend Carlo was gay—or, as he claimed, bisexual—a few years earlier, but when Perry came out to her the following year after their fourth date, she claimed she was swearing off the men of Manhattan forever.

I knew the feeling.

Love wasn’t playing fair with either of us, of course, but it was especially unfair to her. At thirty-five, Denise could still pass for ten years younger. She was attractive, fit, a sparkling conversationalist, and an undyingly loyal friend. Her only problem was that she couldn’t attract the attention of heterosexual men…which, as a heterosexual woman, she considered to be a big problem. Spending a lot of time with me probably didn’t help, of course.

“It took me so long to find Ted,” I said. “It took years. I mean, you’ve known me for fifteen years. How many men have you known that I was serious about?”

“So, it’ll take you some time,” she said, pulling back a loose ribbon of wavy dark hair. “What’s your rush? There are a lot of single people, and they aren’t throwing themselves in front of the subway. Take your time. And let’s face it, I know you think the good one got away, but how good was he if he dropped you overnight for a kid?”

I stirred my coffee distractedly, recognizing that her logic made far more sense than my emotions. She was right. How could I be moping about Ted, glorifying the memory of our relationship, when the bastard didn’t even have the decency to give me a proper good-bye? Just a few short sentences bleeding into a paper towel, which, instead of throwing it out as I should have done, I still kept in a safe place and treated like it was the Declaration of Independence.

I tossed a few dollars on the coffee shop counter. “Let’s move.”

“Where are we moving to?”

“To resolution.”

With Denise in tow, I went home and found the paper towel, opened the window, and let it flutter down to West Eighty-sixth Street, seven stories below.

“Good for you, Drew,” she said, sitting with me in the window, watching it waft along in the breeze.

“Yeah,” I said. “Good for me.” But I was distracted because I thought I saw someone who looked like Ted emerging from the subway station.

It wasn’t him, of course, and I’ll spare you the suspense and reveal right now that Ted never returned to our apartment. But this story isn’t about me and Ted. Ted is over. Ted is the past. The only reason I’ve written about Ted is to give you some perspective.

This story is about what came after Ted. And that wasn’t very pretty, either.