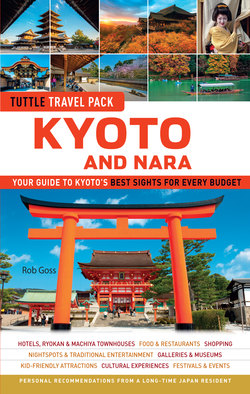

Читать книгу Kyoto and Nara Tuttle Travel Pack Guide + Map - Rob Goss - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

KYOTO & NARA’S

‘Don’t Miss’ Sights

After more than 1,000 years as Japan’s imperial capital, the Kyoto that greets modern-day visitors has numerous reminders of the city’s rich history. The 11 ‘Don’t Miss’ sights here represent the most captivating of those remnants of both ancient Kyoto and the capital before it, Nara, from the decadent golden temple of Kinkaku-ji and the more reserved dry landscape garden at Ryoan-ji to the seemingly endless rows of red torii gateways at Fushimi Inari Shrine and ancient wooden structures at Horyu-ji Temple—the places that make Kyoto and Nara so unforgettable.

1 Kinkaku-ji, the Golden Pavilion

2 Ryoan-ji’s Zen Rock Garden

3 Kiyomizu Temple

4 Nijo Castle

5 Fushimi Inari Shrine

6 The Gion District

7 Arashiyama’s Bamboo Grove

8 Ginkaku-ji Temple

9 Nishiki-koji Food Market

10 Byodo-in Temple

11 Nara’s Horyu-ji Temple

The Zen garden at Ryoan-ji

Ginkaku-ji, the “Silver Pavilion”

Byodo-in Temple in Uji

Geishas in the Gion district

MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR STAY

Part of the enduring charm of Kyoto and Nara is that no matter how long you stay or how often you return, Japan’s former capitals always manage to keep providing something new to discover. One day it could be a temple garden you’ve previously missed, the next a new taste of Japan’s culinary heritage or a snaking side street that leads into the past. Of course, most people don’t have the luxury of spending a month or even a fortnight immersing themselves in the two cities, so what to do and see if (like most visitors) your time in Kyoto and Nara is short?

Your first day could start with two of Kyoto’s star attractions, beginning with Ryoan-ji temple’s cryptic Zen garden (page 10 for details of Ryoan-ji; Chapter 2, page 22 for the full day trip around Northwestern Kyoto) and then taking in the magnificent gilded temple of Kinkaku-ji (page 9) before heading to the gardens at the Daitoku-ji temple complex and finishing among the local crafts of the Nishijin Textile Center (page 24).

On your second day, you could wander from Kiyomizu Temple (page 11) through some of Kyoto’s most atmospheric (and shop-filled) backstreets to Chion-in Temple (Chapter 1, page 26 for this day out). Another day could start at Nijo Castle (Chapter 2, page 33 for this day out), stop by Kyoto Imperial Palace (page 33) and then go shopping mad with a look around Nishiki-koji food market (page 34) to take in the city’s culinary sights and smells and then more retail therapy in the Teramachi arcade, along Shijo-dori and in the Kawaramachi area.

Alternatively, you could opt for a visit to Kinkaku-ji’s understated cousin, the sublime Ginkaku-ji (page 16) in northeastern Kyoto and then stroll the historic Philosopher’s Path south toward the imposing Heian Jingu (with a possible detour to the Nanzen-ji Temple complex on route) before ending the day at the museums and galleries around Okazaki-koen (page 36 for this day out).

If you have time, you could also have a day trip south of Kyoto (Chapter 2, page 44) to visit the gardens of Tofuku-ji Temple, the sprawling Fushimi Inari Shrine and the town of Uji, known for its green tea and the site of the historic Byodo-in Temple (the temple on the back of the ¥10 coin). Or you could head west to the Arashiyama area (Chapter 2, page 40), which is most famous for its bamboo groves but also has some spectacular temples and shrines.

Then there is Nara (Chapter 2, page 48), Japan’s capital before Kyoto in the 8th century and home to several World Heritage-designated temples. Whether you opt to visit as a day trip from Kyoto, as most people do, or take your time with an overnight stay, the city that is often called the “birthplace of Japanese civilization” adds a calming contrast to Kyoto. And for anyone who needs a break from tradition, Japan’s second city, Osaka (page 52), can also be visited in a whirlwind day trip from Kyoto. Whichever options you choose, Kyoto and Nara won’t disappoint.

1 Kinkaku-ji, the Golden Pavilion

The defining image of Kyoto, now a World Heritage Site

Whether it’s accented by a light coating of snow in winter or basking in the clear blue skies of summer, the gilded temple of Kinkaku-ji remains a captivating sight year round. Nothing, save perhaps the sight of a geisha shuffling between teahouses in Gion, says “Kyoto” quite like it.

Originally built in 1397 as a villa for shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, before being repurposed as a Zen temple after Yoshimitsu’s death, what might come as a surprise is that the current incarnation of Kinkaku-ji only actually dates to the mid-1950s, the original having been burned down by a young monk in 1950—an event which sent Japan almost into national mourning. Once the shock waves had passed, however, it didn’t take long for the temple to rise again. By 1955 it had been rebuilt to original specifications with the exception of the gilding that now covers the top two stories—that had to wait until 1987, when Japan’s post-war economic miracle was in full swing.

While that gilding and the shimmering reflection it casts over the pond in front of Kinkaku-ji are undoubtedly the most striking features (and the main reason Kinkaku-ji is one of Kyoto’s most-visited sights), the structure itself is also a fascinating blend of styles. The third story is in the traditional Chinese cha’an style, the second in the buke-zukuri (a style common with warrior aristocrat residences) and the first floor the 11th-century shinden-zukuri style. With all those components combining with such effect, it’s not hard to see why, despite its age, Kinkaku-ji was one of the 17 sites in Kyoto that received joint World Heritage status in 1994.

Opening Times Daily from 9 a.m.–5 p.m. Getting There You can take bus #101 or #205 to the Kinkaku-ji Michi bus stop or #59 and #12 to the Kinkaku-ji Mae bus stop. It’s a short, well-marked route to the temple from either bus stop.Contact www.shokoku-ji.jp Admission Fee ¥400. While in the area Combine a trip to Kinkaku-ji with a day out in northwestern Kyoto (page 22) that also takes in the Zen rock garden at Ryoan-ji, the gardens of Daitoku-ji, and the Nishijin Textile Center.

2 Ryoan-ji’s Zen Rock Garden

Japan’s most enigmatic sight

Before the tour buses begin their daily procession to Ryoan-ji, the fleeting calm before the storm at the temple offers early birds a moment of Zen contemplation in the peace and quiet the designer of Ryoan-ji’s garden likely intended. And there’s plenty to contemplate from the wooden steps beside the garden at this UNESCO World Heritage site. Despite years of study and argument, nobody knows for sure when the garden was made or who made it, nor can anybody agree on what the designer was trying to express.

The karesansui (dry landscape) garden only measures 30 by 10 meters (100 x 30 feet), but the cryptic manner in which its 15 rocks are arranged on a bed of off-white sand within that rectangle have been argued to represent all sorts of things—from small islands on an ocean to a tiger carrying a cub across a river and even a map of Chinese Zen monasteries. As for the who and when of the garden’s creation, the garden was most likely created just after the bloody Onin War of 1467–77, after which much of Kyoto had to be rebuilt, and judging by the style and historical records the man behind it is most likely an artist and landscape gardener called Soami, even though the names of other landscapers are carved into some of the garden’s rocks.

Whoever it may have been, they have left a challenge for visitors. See if you can find a point from where you can see all 15 rocks at the same time. The designer has managed to lay out the rocks in such a way that you won’t be able to see more than 14 at once, unless, it is said, you have reached the point of spiritual enlightenment. Most likely the only way to see all 15 is to check out the small replica of the garden on display just inside the main temple building; it won’t bring enlightenment but it’ll give you a better understanding of the sweeping patterns in the sand and the way the rocks have been grouped.

Opening Times Mar.–Nov. 8 a.m.–5 p.m., Dec.– Feb. 8.30 a.m.–4.30 p.m. Getting There Take buses #50 or #55 to the Ritsumeikan Daigaku-mae bus stop or bus #59 to Ryoanji-mae. Ryoan-ji is also a seven-minute walk from Ryoanji-michi Station on the Keifuku Kitano Line. Contact www.ryoanji.jp Admission Fee ¥500. While in the area After Ryoan-ji head to another of Kyoto’s main attractions, the gilded Kinkaku-ji (pages 9 and 22), which is just over a kilometer to the northeast and easily reached by bus from Ryoan-ji.

3 Kiyomizu Temple

Tradition and nature—a view of Kyoto from on high

From haiku poetry to the (Chinese originated) concept of “borrowed scenery” in garden and architectural design, traditional Japanese culture is deeply rooted in an appreciation and reflection of nature and especially the seasons. Kiyomizu Temple in eastern Kyoto is a particularly fine example of that.

The temple’s main hall (Hondo) has a backdrop that marks the seasons. In spring (the natural, academic and fiscal beginning to the year in Japan) the Hondo is accented by the delicate pinks of cherry blossom. Come summer, it’s immersed in a sea of lush green that gives way to rich reds and yellows in autumn, before the foliage thins and is occasionally dappled with snow in winter.

Kiyomizu Temple is comprised of many elements (including a three-storied pagoda that is especially magical when occasionally illuminated at night), but it’s the Hondo that steals the show. Dating to the 1600s, like many of Kiyomizu’s current buildings (although the temple was established much earlier in 778), the hall is built on a rock face that overlooks a small valley and features a protruding wooden veranda held up by 12-meter (40-foot) high keyaki (Japanese Zelkova) pillars.

Not only are the hall and its veranda one of Kyoto’s most memorable images, a Japanese idiom equivalent to “take the plunge” was born from it. It used to be said that anyone who leapt from the overhanging veranda and survived would have their dreams answered, while anyone who died trying would be rewarded by sainthood. It might sound like everyone is a winner with that deal, but don’t be tempted to leap yourself. Taking the plunge from Kiyomizu Temple was illegalized back in 1872 in response to a spate of leaping mishaps.

Opening Times The main hall is open daily from 6 a.m.–6 p.m. Getting There From Kyoto Station head to the Gojo-zaka bus stop, served by City Bus #100 and #206. Kiyomizu Temple is a ten-minute walk uphill from there (just follow the crowds). From the Kawaramachi and Shijo areas, you can catch City Bus #207 to the Kiyomizu-michi bus stop. Contact www.kiyomizudera.or.jp. Admission Fee ¥300. While in the area After the temple, check out the stores and cafes on the sloping Ninenzaka, Sannen-zaka, and Kiyomizuzaka streets nearby (page 26). You’ll find lots of old craft shops and places to try traditional sweets.

4 Nijo Castle

An Edo-era symbol of the Shogun’s power and prestige

Constructed in 1603 by the first Edo-era shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Nijo Castle (Nijo-jo in Japanese) was born as a powerful statement of intent, serving as a potent reminder to all in Kyoto of Tokugawa strength. Although Ieyasu ruled from afar in Tokyo (then called Edo), the mighty Nijo-jo left no one in doubt that Big Brother was watching and ready to pounce.

Located in the heart of Kyoto, just northwest of Nishiki and Shijo (see page 33 for a full day out in the area), Nijo-jo’s grounds are spread out over 275,000 m² (329,000 yd²) in which modern-day visitors will find a pair of palaces (the Hinomaru and the Ninomaru), remains of fortifications and landscaped gardens that together saw Nijo-jo granted World Heritage designation. In particular, it’s the Ninomaru palace that stands out. Its gardens, designed by famed Edo-era landscape designer Kobori Enshu, combine pines (to symbolize longevity) and rocks (representing loyalty) to appease Tokugawa’s ego, while inside the palace itself are some of the most ornate screen paintings and carvings in the country—the outer chambers, which would have been used for lower-ranked visitors, decorated with fear-inducing paintings that evoke strength and power, yet the inner chambers for trusted and higher-ranked guests being home to more calming, beautiful imagery.

Through the 265 years of Tokugawa rule, Nijo-jo’s defenses were never put to the test, but should anyone have been brave enough to launch an attack, the remaining giant stone walls encircling the castle’s grounds suggest that Nijo-jo would have withstood almost any onslaught. As for attacks more subtle, the artistry at the Ninomaru wasn’t restricted to paintings on the walls and doors—ninja beware, as the “nightingale” floors in the Ninomaru palace are designed to squeak like birds should an intruder try to enter by stealth.

Opening Times Daily 8.45 a.m.–5 p.m. (last entry 4 p.m.). Getting There From Kyoto Station you can get City Bus #9, #50 or #101 to Nijo-jo-mae bus stop. The same bus stop can also be reached from Karasuma Station by City Bus #12 or #101. Contact www.city.kyoto.jp/bunshi/nijojo/english Admission Fee ¥600. While in the area Combine Niji-jo with the other sites featured in the tour of central Kyoto on page 33, including Kyoto Imperial Palace Park, Nishikikoji food market, and the stores along Shijo-dori and in the Kawaramachi area.

5 Fushimi Inari Shrine

Kyoto at its mesmerizing best

Eye catching, enchanting, iconic—there are many ways to describe Fushimi Inari Taisha (shrine) in southern Kyoto. You could add “good exercise” to the list, too, if you decide to walk around the whole shrine.

Dating to the early 700s, Fushimi Inari Shrine is best known for its 10,000 vermilion torii gateways, which cover four kilometers (two and a half miles) of winding pathways that lead up and around a wooded mountain punctuated by small shrines and small fox statues, all combining to create an atmosphere that is at turns mystical, at others eerie, but always begging to be explored.

The grand scale of Fushimi Inari Shrine reflects its importance. It’s the head shrine of some 40,000 other Inari shrines across Japan, all dedicated to one of Shinto’s principal deities, Inari Okami, the god of rice, sake, prosperity, industry, fertility and numerous other things. Inari has certainly collected an impressive portfolio over the centuries. He or she has also collected numerous guises—Inari has been depicted as male and female, old and young, as a bodhisattva, and even as a fox. It’s the latter that often causes some confusion as the stone foxes scattered about Fushimi Inari Shrine are frequently called Inari, when in this case they are actually supposed to be just foxes (kitsune) acting as Inari’s messengers.

If you were to come in early January, the shrine would be packed with people doing the traditional hatsu-mode—the first visit of the year to a shrine to offer prayers for good fortune for the year ahead. In fact, on any visit here, you will see a fairly steady flow of business people and others hoping for a little fortune from Inari. Whenever you visit, there’s a good chance you won’t find anywhere else in Kyoto to be quite as mesmerizing.

Opening Times Daily from dawn to dusk. Getting There About a 5-minute walk from Inari Station on the JR Nara Line or 10 minutes from Fushimi-Inari Station on the Keihan Line. For a day out in southern Kyoto that includes Fushimi Inari Shrine and other sights, see Chapter 2, page 44. Contact http://inari.jp Admission Fee Free. While in the area Do Fushimi Inari Shrine as a day out in southern Kyoto that also includes the gardens of Tofukuji Temple and the green tea and Byodo-in Temple in Uji (page 46).

6 The Gion District

Kyoto’s famed geisha and entertainment district

Gion isn’t the only place in Kyoto where you will find geisha, but it is the most famous. The backstreets here, lined with wooden machiya townhouses that serve as high-end restaurants and exclusive teahouses—lowly-lit lanterns hanging out front of an evening—provide the perfect backdrop for the white-faced geisha and their ornately decorated kimono as they flit between appointments.

Some of the geisha you see in Gion will be apprentices known as maiko, while some will be full geisha (referred to in Kyoto as geiko), who would have been through at least five years of training, not just in how to dress and behave like a geisha, but in traditional pastimes such as flower arranging, the tea ceremony, and performing arts. The question is: can you tell the difference? One way is to look at the belt. A maiko’s kimono belt (called an obi) will drop down at the back to almost touch the floor, while a geiko will have her obi neatly folded like a square on her back. The maiko might also have accessories in her hair, where a geisha won’t, and while a geisha will always wear flat zori sandals, you might also see a maiko in platformed footwear.

If you want to spot some geiko or maiko, be in Gion around 5.30pm to 6pm, when many are on their way to their evening appointments. Then follow some simple rules if you are going to try photographing them—don’t block their path to get your shot (from behind or the side is ok), don’t try and pose with them, don’t stalk (some busloads of visitors do!) and don’t photograph them if they are walking with a client.

Getting There From Kyoto Station, buses #100 and #206 run to the Gion bus stop. The area can also be accessed by Gion Shijo Station on the Keihan Line and (a slightly longer walk) Kawaramachi Station on the Hankyu Line. To explore Gion as part of a half-day out, see Chapter 2, page 30. While in the area You’d need some heavy connections and deep pockets to get into many of Gion’s restaurants and teahouses, but not everything is pricey or off limits. Try Gion Tokuya (gion-tokyuya.jp) for green tea and sweets in traditional surrounds. Or, look at the geisha shows on page 66, if you are happy to drop a couple of hundred dollars on what will be an unforgettable night out.

7 Arashiyama’s Bamboo Grove

A glimpse of Kyoto’s sublime natural beauty

As Kyoto’s attractions go, the bamboo grove in Arashiyama has to be one of the most beguilling. It’s certainly one of the most photographed. Running between two of the Arashiyama area’s other main attractions, Tenryu-ji and the Okochi-sanso Villa, strolling through the narrow walkways of the bamboo grove is simply enchanting. The light, often filtered a soft green through the towering bamboo’s canopy, produces an otherworldly feel that seems to send visitors into a photographic trance. You can almost guarantee you will see someone lying on their back, camera to the sky, trying (usually in vain) to get a prime, people-free angle of the bamboo stalks as they gently sway in the breeze.

Then there’s the sound. The eerie creaking noises the bamboo makes adds to the surreal sense of the place, so much so that the Ministry of the Environment has included the bamboo forest on its oddly-named “100 Soundscapes of Japan” list (one of countless, sometimes seemingly pointless “100…of Japan” lists that the Japanese government and other organizations are quite fond of issuing). You just have to make sure you don’t get stuck between high-school touring groups or you won’t hear anything but chatter.

One thing to note before visiting is that the bamboo forest won’t take much more than 30 minutes (maybe much less), so don’t plan on heading out to Arashiyama just for it. Do it as part of a longer walk around Arashiyama (see page 40 for that). Like many other popular sights in Kyoto, try to get there early, too, as that will give you the best chance of not sharing the bamboo with busloads of tour groups.

Opening Times Dawn to dusk daily. Getting There About a ten-minute walk from Saga Arashiyama Station on the JR Sagano Line or Keifuku Arashiyama Station on the Randen Line. Admission Fee Free. While in the area Follow the half-day tour on page 40 to explore more of Arashiyama, which includes Tenryu-ji and the plush Okochi-sanso Villa, and also some nice stores and a footbath to finish at the station.

8 Ginkaku-ji Temple

The Silver(less) Pavilion

Kinkaku-ji’s unadorned cousin, Ginkaku-ji, has got the natural look down pat. The Silver Pavilion, as it’s often known in English (Gin means silver), was supposedly going to be covered in silver leaf when it was built as a shogun’s retirement villa during the 1480s, but for reasons nobody can decide on today that never happened.

It’s most likely that shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, the man behind Ginkaku-ji’s construction (and the grandson of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who was responsible for the gilded Kinkaku-ji), simply ran out of money to fund the project, while others speculate that he never had any real intention of spending a fortune on all that silver. Whatever the reason, Ginkaku-ji, which became a Zen temple (officially called Jisho-ji) after Yoshimasa’s death, is fine just the way it is.

Yoshimasa was said to have been a great patron of the arts, promoting such pursuits as poetry and the tea ceremony, which he pursued in his retirement at Ginkaku-ji, and the temple’s understated beauty is certainly more representative of Japanese artistic sensibilities than the brashness of Kinkaku-ji. The view over Ginkaku-ji from the small wooded hill within the temple’s grounds is worthy of a haiku. The grounds are lush with moss and trees that contrast with the simple raked sand garden, where the raised ripples in the white sand are said to be designed to reflect the moon’s rays. The pond positioned in front of Ginkaku-ji sometimes ripples in the breeze, too, as its catches reflections of the two-story thatched temple. It all combines to make Ginkaku-ji uniquely special.

Opening Times Daily Mar.–Nov. 8.30 a.m.–5 p.m., Dec.–Feb. 9 a.m.–4.30 p.m. Getting There Take buses #5, #17 or #100 to the Ginkakuji-mae bus stop. Or look at Chapter 2, page 36, to see how Ginkaku-ji can be combined with a stroll along the nearby Philosopher’s Path. Contact www.shokoku-ji.jp Admission Fee ¥500. While in the area After Ginkaku-ji walk down the Philosopher’s Path as part of the day out detailed on page 36. The Philosopher’s Path has a few nice cafes and stores on and just off it including Yojiya, where you can sip tea on tatami accompanied by some lovely garden views (page 37).

9 Nishiki-koji Food Market

Kyoto’s oldest market is a sensory delight

To stroll along the approximately 500-meter (1,640-foot) covered street that makes up Nishiki-koji food market is to journey through the colors, aromas and flavors of Kyoto’s culinary heritage. Running parallel to Shijo Street, one block to the north, the vibrant Nishiki-koji began life in 1616 as a fish market, but over the centuries its scope has broadened to encapsulate an incredible range of regional specialties and traditional traders.

For visitors with a sweet tooth, you’ll find Swiss baumkauchen cake with a green tea flavored twist, colorful hard candies that look like ornate marbled glass, and traditional Japanese sweets such as dango (rice flour dumpling), warabi mochi (a thick, jelly-like sweet made with bracken starch) and manju (dough buns filled with red bean paste). In keeping with Nishiki’s seafood roots, there are also stores that specialize in river fish, dried fish and cured fish, while among the rest of Nishiki’s 126 stores you’ll also find tofu and yuba (tofu skin) variations, pickles that come in almost every conceivable color, a variety of hand-made noodles, not to mention simple greengrocers, and several cafes and eateries. There’s even cheap and cheerful b-kyu gurume (lit. b-grade gourmet) on hand in the shape of tako-yaki (octopus chunks deep-fried in batter), amongst other things.

When it’s too wet or too hot outside for temple hopping, an hour or two in the market should be at the top of your list of things to do. Whatever the weather, Nishiki-koji delivers a treat for the senses and an insight into Kyoto’s culinary traditions.

Opening Times Daily 10 a.m.–5 p.m., although some stores have fixed days off. Getting There A several-minute walk from Shijo Station (Karasuma subway line), Karasuma Station (Hankyu Line) and Kawaramachi Station (Hankyu Line). Also handily served by City Bus #5 via the Shijo Takakura bus stop. Contact www.kyoto-nishiki.or.jp Admission Fee Free. While in the area Connected to Nishiki is the covered Teramachi arcade (page 33), a great place to browse craft shops, art galleries, book shops and many other places that off er things above and beyond typical tourist fare.

10 Byodo-in Temple

The historic “Phoenix Hall” and its priceless treasures

If you have a ¥10 coin handy, flip it over and you’ll see one of Japan’s most recognizable historic buildings—Byodo-in’s Phoenix Hall spreading its wings as if about to take flight. Located south of Kyoto, in the town of Uji (page 44 for a day trip), the Phoenix Hall makes it onto modern-day currency for good reason. Not only is the design so striking, it’s the only structure at Byodo-in Temple that dates to the temple’s original construction in 1052–1053, when Fujiwara no Yorimichi, the son of the then emperor’s closest adviser, decided to convert an old aristocrat’s villa into a Buddhist temple.

While the outside of the Phoenix Hall leaves many visitors in a photographic frenzy, snapping away at the hall and its watery reflection, the inside of the hall is just as impressive thanks to a collection of exquisite historic artwork. Most notably that includes a seated statue of the Amitabha Tathagata Buddha sculpted by Heian-era (794–1185) master sculptor of Buddhist images Jocho, which was enshrined inside the hall in 1053 to celebrate its construction.

As a reminder that despite the temple’s beauty, brutality was never all that far away in classical Japan, look out for a fan-shaped marker on the temple’s grounds placed to mark the spot where prominent aristocrat and poet Minamoto no Yorimasa committed ritual suicide in the 12th century after losing control of Byodo-in Temple in battle against the Taira clan. The Minamoto clan would go on to win the resulting Genpei War against the Taira and with it rule Japan under the Kamakura shogunate (1192–1333), although in his death poem Yorimasa must have feared all was lost: Like an old tree / From which we gather no blossoms / Sad has been my life / Fated to bear no fruit.

Opening Times Daily 8.30 a.m.–5.30 p.m. The Phoenix Hall viewing sessions (every 20 minutes; maximum of 50 people at a time) run from 9.10 a.m.–4.30 p.m. Getting There A ten-minute walk from Uji Station, which is 16 minutes from Kyoto on the JR Nara Line. Contact www.byodoin.or.jp Admission Fee ¥600, plus an additional ¥300 to go inside the Phoenix Hall. While in the area Uji is famed for tea and the streets that lead to Byodo-in Temple are lined with small stores that sell all manner of green tea inspired goods. On a hot day, try one of the slightly bitter green tea ice creams, or pick up an unusual souvenir like green tea liqueur or green tea noodles.

11 Nara’s Horyu-ji Temple

An early outpost of Japanese Buddhism

Deciding on just one ‘Don’t Miss’ to represent Nara is the kind of task that can leave a man awake at night. You could pick Todai-ji Temple (page 50), which is famous in part for its 15-meter (50-foot)-high bronze statue of Buddha, or maybe you could opt for Kofuki-ji Temple (page 48) because of its 600-year-old five-story pagoda, the original of which was moved to Nara from Kyoto in the 8th century. Then there is Horyu-ji Temple, which is home to not only an even older five-story pagoda, but also a building called the Kon-do (Golden Hall) that’s believed to have been built around 670 AD, thereby making it the world’s oldest wooden building. It almost came down to a game of Japan’s favorite decision maker, janken (rock, paper, scissors), but in the end, age won out.

Founded in 607 AD, 50 years after Buddhism first arrived in Japan, Horyu-ji Temple was a major base from which the recently imported religion Buddhism spread across Japan under the patronage of Horyu-ji’s founder Prince Shotoku (574–622AD). While the complex and its ancient structures are an obvious main attraction (with a scale and splendor that serve to highlight how quickly and deeply Buddhism established itself in Japan), Horyu-ji Temple is also known for its treasures. Some of Japanese Buddhism’s most precious relics are kept at Horyu-ji’s Kon-do today, including the original Medicine Buddha that Shotoku supposedly built Horyu-ji Temple to hold and a bronze image of Buddha dated to 623, while in the 8th-century Yumedono building in the complex’s eastern precinct is the jewel in Horyu-ji’s crown: a 178.8-cm (5-foot 10-inch-high) statue thought to be a life-size replica of Prince Shotoku, and which for centuries was kept hidden from all under a white cloth, only finally being uncovered in 1884.

Opening Times Daily 8 a.m.–4.30 p.m. Getting There Nara is 40 minutes from Kyoto on the Kintetsu-Kyoto Line’s Limited Express and can also be reached by JR Lines from Kyoto and Osaka. The JR Yamatoji Line runs from JR Nara Station to Horyuji Temple (12 mins). Contact www.horyuji.or.jp Admission Fee ¥1,500. While in the area Look at the full guide to Nara (page 48), which will also take you to places like Todai-ji Temple (mentioned above) as well as the historic Nara-machi area (page 50) and its old wooden buildings that now house a great selection of craft stores, cafes and restaurants.