Читать книгу Japanese Inns and Hot Springs - Rob Goss - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

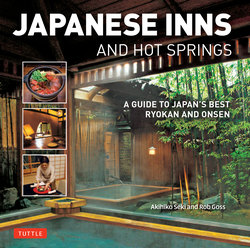

ОглавлениеA TRADITION OF FINE HOSPITALITY

As anyone who has stayed at a ryokan will tell you, the experience is more than a window to classic Japan, it affords an opportunity to immerse yourself in tradition; to experience old Japan as the Japanese have done for generations—in a way that is unadulterated, unhurried, and undoubtedly unforgettable.

Like so much of Japan’s richly woven cultural tapestry, the ryokan has a long and winding history that has seen it develop from humble beginnings to today’s pampering retreat. Delve into the ryokan’s roots and you’ll be reaching back to the Nara period (710–784), a time when the political, social and religious structures of classical Japanese civilization were taking shape. It was then that simple but free rest houses for travelers called fuseya first appeared. They were run by Buddhist monks to help keep travelers from the perils of the road.

In the Heian era (794–1191), a rise in the popularity of pilgrimages among the elite classes saw a twist on fuseya arise, with feudal manors and temples opening themselves to pilgrims. It’s hard to know just how spartan the latter—called shukubo—would have been back then, but the modern-day version of temple accommodation is a fascinating experience for pilgrims and tourists alike. In Koya-san, the mountain-top town home to the Shingon sect of Buddhism, almost half of the one hundred or so temples and monasteries that hug the mountain provide almost ryokan-like shukubo, with modest tatami-mat rooms but exquisite vegetarian shojin-ryori cuisine and opportunities to experience temple life by attending morning prayers and meditation.

It’s difficult to entirely separate shukubo from ryokan—many current ryokan, for example, were once shukubo. But as temple lodgings developed on major travel routes, along with the development of roads, bridges, and small towns, so did accommodation for non-pilgrims. Initially, this took the form of simple lodgings called kichin-yado, where guests received no meals but were able to seek shelter from the elements. Guests were charged not for their rooms here, but for the wood they would use to cook and keep warm with. By the time of the Edo era (1603–1868), a developing economy and increased internal trade saw more travel, and the appearance of accommodation called hatago, offering merchants and other travelers a more comprehensive version of kichin-yado, with meals provided and accommodation fees charged.

Personal service at a ryokan not only means lavish ten-course meals in your room but occasionally the chef may even serve you personally, as shown here at Suisen (pages 116–121).

At this time, with the Tokugawa shogunate strictly keeping provincial lords in check, a high-end version of hatago also came in to being, and besides being another stepping stone toward today’s ryokan, its own roots reveal much about the politics of the Edo era. So the shogunate could keep a close eye on them, daimyo (feudal lords) were obliged to alternate annually between living in their own regions and living in the capital Edo (now called Tokyo). This saw the rise of honjin lodgings for the daimyo on common travel routes, as well as less fancy lodgings for their staff, but even with these and hatago in place another development was needed before the ryokan became what it is today—widespread travel for leisure.

From the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when military rule with its harsh travel restrictions was abolished, travel and sightseeing as a pastime began to grow in popularity, initially among the wealthy, then spreading to a broad spectrum of society from the end of the Second World War onwards. As a result, ryokan—the kanji characters for which literally translate to something like “travel lodgings”—sprang up all over Japan, particularly in popular tourist destinations and in areas blessed with natural hot springs, offering a relaxing combination of traditional peace and quiet, hospitality, fine cuisine, and (in many cases) hot-spring bathing. The ryokan offers pampering, but also an opportunity for Japanese living increasingly hectic, modern lives to slow down; to embrace and celebrate their traditions; to feel Japanese.

This modern hot-spring pool at Gora Kadan (see pages 20-25) is carved from a block of solid granite.

The opportunity to experience a traditional Japanese home interior first-hand is one of the great joys of staying at a ryokan. Shown here is an elegant room at Yoshida Sanso (see pages 76–81).