Читать книгу Love Wins: At the Heart of Life’s Big Questions - Rob Bell - Страница 6

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Here Is the New There

First,

heaven.

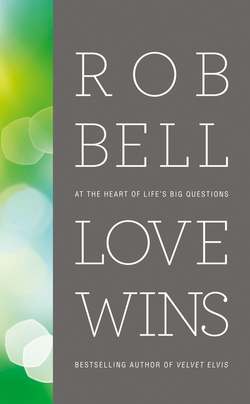

This is a photograph of a painting that hung on a wall in my grandmother’s house from before I was born. As you can see, in the center of the picture is a massive cross, big enough for people to walk on. It hangs suspended in space, floating above an ominous red and black realm that threatens to swallow up whoever takes a wrong step. The people in the picture walking on the cross are clearly headed somewhere—and that somewhere is a city. A gleaming, bright city with a wall around it and lots of sunshine.

It’s as if Thomas Kinkade and Dante were at a party, and one turned to the other sometime after midnight and uttered that classic line “You know, we really should work together sometime . . .”

When I asked my sister Ruth if she remembered this painting, she immediately replied, “Of course, it gave us all the creeps.”

It’s striking what we remember, isn’t it? An image or idea can lodge itself in our consciousness to such a degree that, years later, it’s still there. This is especially true when it comes to religion.

My wife, Kristen, and I often talk about raising our kids in such a way that they have as little as possible to unlearn later on in life.

One of the only violent images Jesus ever uses is when he speaks about those who cause children to stumble. With a shockingly hyperbolic flourish, he declares that the only fitting punishment is to tie a giant stone around their neck and throw them into the sea (Matt. 18).

Death by drowning—Jesus’s idea of punishment for those who lead children astray. A haunting warning if there ever was one about the spongelike nature of a child’s psyche.

I’m not saying that my grandma’s painting did that, but it clearly unnerved at least two of us.

I show you this painting not because of its astounding ability to somehow fuse Dungeons and Dragons, Billy Graham, and that barbecue pit your uncle made out of half of a fifty-gallon barrel into one piece of art, but because this painting tells a story.

It’s a story of movement,

from one place to the next,

from one realm to another,

from death to life,

with the cross as the bridge, the way, the hope.

From what we can see, the people in the painting are going somewhere, somewhere they’ve chosen to go, and they’re leaving something behind so that they can go there.

But the story also tells us something else,

something really, really important,

something significant about location.

According to the painting,

all of this is happening somewhere else.

Giant crosses do not hang suspended in the air in the world that you and I call home. Cities do not float. And if you tripped and fell off the cross/sidewalk in this world, you would not free-fall indefinitely down into an abyss of giant red caves and hissing steam.

I show you this painting because, as surreal as it is, the fundamental story it tells about heaven—that it is somewhere else—is the story that many people know to be the Christian story.

Think of the cultural images that are associated with heaven: harps and clouds and streets of gold, everybody dressed in white robes.

(Does anybody look good in a white robe? Can you play sports in a white robe? How could it be heaven without sports? What about swimming? What if you spill food on the robe?)

Think of all of the jokes that begin with someone showing up at the gates of heaven, and St. Peter is there, like a bouncer at a club, deciding who does and doesn’t get to enter.

For all of the questions and confusion about just what heaven is and who will be there, the one thing that appears to unite all of the speculation is the generally agreed-upon notion that heaven is, obviously, somewhere else.

And so the questions that are asked about heaven often have an otherworldly air to them:

What will we do all day?

Will we recognize people we used to know?

What will it be like?

Will there be dogs there?

I’ve heard pastors answer, “It will be unlike anything we can comprehend, like a church service that goes on forever,” causing some to think, “That sounds more like hell.”

And then there are those whose lessons about heaven consist primarily of who will be there and who won’t be there. And so there’s a woman sitting in a church service with tears streaming down her face, as she imagines being reunited with her sister who was killed in a car accident seventeen years ago. The woman sitting next to her, however, is realizing that if what the pastor is saying about heaven is true, she will be separated from her mother and father, brothers and sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles, and friends forever, with no chance of any reunion, ever. She in that very same moment has tears streaming down her face too, but they are tears of a different kind.

When she asks the pastor afterward if it’s true that, because they aren’t Christians none of her family will be there, she’s told that she’ll be having so much fun worshipping God that it won’t matter to her. Which is quite troubling and confusing, because the people she loves the most in the world do matter to her.

Are there other ways to think about heaven, other than as that perfect floating shiny city hanging suspended there in the air above that ominous red and black realm with all that smoke and steam and hissing fire?

I say yes, there are.

___________________

In Matthew 19 a rich man asks Jesus: “Teacher, what good thing must I do to get eternal life?”

For some Christians, this is the question, the one that matters most. Compassion for the poor, racial justice, care for the environment, worship, teaching, and art are important, but in the end, for some followers of Jesus, they’re not ultimately what it’s all about.

It’s “all about eternity,” right?

Because that’s what the bumper sticker says.

There are entire organizations with employees, websites, and newsletters devoted to training people to walk up to strangers in public places and ask them, “When you die and God asks you why you should be let into heaven, what will you say?” There are well-organized groups of Christians who go door-to-door asking people, “If you were to die tonight, where would you go?”

The rich man’s question, then, is the perfect opportunity for Jesus to give a clear, straightforward answer to the only question that ultimately matters for many.

First, we can only assume, he’ll correct the man’s flawed understanding of how salvation works. He’ll show the man how eternal life isn’t something he has to earn or work for; it’s a free gift of grace.

Then, he’ll invite the man to confess, repent, trust, accept, and believe that Jesus has made a way for him to have a relationship with God.

Like any good Christian would.

Jesus, however, doesn’t do any of that.

He asks the man: “Why do you ask me about what is good? There is only one who is good. If you want to enter life, keep the commandments.”

“Enter life?”

Jesus refers to the man’s intention as “entering life”? And then he tells him that you do that by keeping the commandments? This wasn’t what Jesus was supposed to say.

The man, however, wants to know which of the commandments. There are 613 of them in the first five books of the Bible, so it’s a fair question. In the culture Jesus lived in, an extraordinary amount of time was spent in serious discussion and debate about these 613 commandments, dissecting and debating just how to interpret and obey them.

Were some more important than others?

Could they be summarized?

What do you do when your donkey falls in a hole on the Sabbath?

Rescuing your donkey would be work, and that would be breaking the Sabbath commandment to rest, but there were also commands to protect and preserve life, including the life of donkeys, so what happens when obeying one commandment requires you to break another?

The Ten Commandments were central to this discussion because of the way in which they covered so many aspects of life in so few words. Jesus refers to them in answering the man’s question about “which ones” by listing five of the Ten Commandments. But not just any five. The first four of the commandments were understood as dealing with our relationship with God—Jesus doesn’t list any of those. The remaining six deal with our relationships with each other. Jesus mentions five of them, leaving one out.

The man hears Jesus’s list of five and insists he’s kept them all.

Jesus then tells him, “Go, sell your possessions, and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven,” which causes the man to walk away sad, “because he had great wealth.”

Did we miss something?

The big words, the important words—“eternal life,” “treasure,” “heaven”—were all there in the conversation, but they weren’t used in the ways that many Christians use them.

Shouldn’t Jesus have given a clear answer to the man’s obvious desire to know how to go to heaven when he dies? Is that why he walks away—because Jesus blew a perfectly good “evangelistic” opportunity? How does such a simple question—one Jesus could have answered so clearly from a Christian perspective—turn into such a convoluted dialogue involving commandments and treasures and wealth and ending with the man walking away?

The answer,

it turns out,

is in the question.

When the man asks about getting “eternal life,” he isn’t asking about how to go to heaven when he dies. This wasn’t a concern for the man or Jesus. This is why Jesus doesn’t tell people how to “go to heaven.” It wasn’t what Jesus came to do.

Heaven, for Jesus, was deeply connected with what he called “this age” and “the age to come.”

In Matthew 13 Jesus speaks of a harvest at the “end of the age,” and in Luke 20 he teaches about “the people of this age” and some who are “considered worthy of taking part in the age to come.” Sometimes he describes the age to come simply as “entering life,” as in Mark 9—“it’s better for you to enter life maimed”—and other times he teaches that by standing firm “you will win life [in the age to come],” as in Luke 21. And then, just before he leaves his disciples in Matthew 28, Jesus reassures them that he is with them “always, to the very end of the age.”

Jesus’s disciples ask him in Matthew 24, “What will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?” because this is how they had been taught to think about things—

this age,

and then the age to come.

We might call them “eras” or “periods of time”:

this age—the one we’re living in—and the age to come.

Another way of saying “life in the age to come” in Jesus’s day was to say “eternal life.” In Hebrew the phrase is olam habah.

What must I do to inherit olam habah?

This age,

and the one to come,

the one after this one.

When the wealthy man walks away from Jesus, Jesus turns to his disciples and says to them, “No one who has left home or wife or brothers or sisters or parents or children, for the sake of the kingdom of God will fail to receive many times as much in this age, and in the age to come eternal life” (Luke 18).

Now, the English word “age” here is the word aion in New Testament Greek. Aion has multiple meanings—one we’ll look at here, and another we’ll explore later. One meaning of aion refers to a period of time, as in “The spirit of the age” or “They were gone for ages.” When we use the word “age” like this, we are referring less to a precise measurement of time, like an hour or a day or a year, and more to a period or era of time. This is crucial to our understanding of the word aion, because it doesn’t mean “forever” as we think of forever. When we say “forever,” what we are generally referring to is something that will go on, year after 365-day year, never ceasing in the endless unfolding of segmented, measurable units of time, like a clock that never stops ticking. That’s not this word. The first meaning of this word aion refers to a period of time with a beginning and an end.

So according to Jesus there is this age, this aion—

the one they, and we, are living in—

and then a coming age,

also called “the world to come”

or simply “eternal life.”

Seeing the present and future in terms of two ages was not a concept or teaching that originated with Jesus. He came from a long line of prophets who had been talking about life in the age to come for hundreds of years before him. They believed that history was headed somewhere—not just their history as a tribe and nation, but the history of the entire universe—because they believed that God had not abandoned the world and that a new day, a new age, a new era was coming.

The prophet Isaiah said that in that new day

“the nations will stream to” Jerusalem,

and God will

“settle disputes for many peoples”;

people will “beat their swords into plowshares

and their spears into pruning hooks” (chap. 2).

As we would say,

peace on earth.

Isaiah said that everybody will walk

“in the light of the LORD”

and

“they will neither harm nor destroy”

in that day.

The earth, Isaiah said, will be

“filled with the knowledge of the LORD

as the waters cover the sea” (chap. 11).

He described

“a feast of rich food for all peoples”

because God will

“destroy the shroud that enfolds all peoples,

the sheet that covers all nations,

he will swallow up death forever.”

God “will wipe away the tears from all faces”;

and “remove his people’s disgrace from all the earth” (chap. 25).

The prophet Ezekiel said that people will be given

grain and fruit and crops and new hearts and new spirits (chap. 36).

The prophet Amos promised that everything will be

repaired and restored and rebuilt and

“new wine will drip from the mountains” (chap. 9).

Life in the age to come.

If this sounds like heaven on earth,

that’s because it is.

Literally.

A couple of observations about the prophets’ promises regarding life in the age to come.

First, they spoke about “all the nations.” That’s everybody. That’s all those different skin colors, languages, dialects, and accents; all those kinds of food and music; all those customs, habits, patterns, clothing, traditions, and ways of celebrating—

multiethnic,

multisensory,

multieverything.

That’s an extraordinarily complex, interconnected, and diverse reality, a reality in which individual identities aren’t lost or repressed, but embraced and celebrated. An expansive unity that goes beyond and yet fully embraces staggering levels of diversity.

A racist would be miserable in the world to come.

Second, one of the most striking aspects of the pictures the prophets used to describe this reality is how earthy it is. Wine and crops and grain and people and feasts and buildings and homes. It’s here they were talking about, this world, the one we know—but rescued, transformed, and renewed.

When Isaiah predicted that spears would become pruning hooks, that’s a reference to cultivating. Pruning and trimming and growing and paying close attention to the plants and whether they’re getting enough water and if their roots are deep enough. Soil under the fingernails, grapes being trampled under bare feet, fingers sticky from handling fresh fruit.

It’s that green stripe you get around the sole of your shoes when you mow the lawn.

Life in the age to come.

Earthy.

Third, much of their vision of life in the age to come was not new. Deep in their bones was the Genesis story of Adam and Eve, who were turned loose in a garden to name the animals and care for the earth and enjoy it.

To name is to order, to participate, to partner with God in taking the world somewhere.

“Here it is,

a big, beautiful, fascinating world,”

God says.

“Do something with it!”

For there to be new wine, someone has to crush the grapes.

For the city to be rebuilt, someone has to chop down the trees to make the beams to construct the houses.

For there to be no more war, someone has to take the sword and get it hot enough in the fire to hammer into the shape of a plow.

This participation is important, because Jesus and the prophets lived with an awareness that God has been looking for partners since the beginning, people who will take seriously their divine responsibility to care for the earth and each other in loving, sustainable ways. They centered their hopes in the God who simply does not give up on creation and the people who inhabit it. The God who is the source of all life, who works from within creation to make something new. The God who can do what humans cannot. The God who gives new spirits and new hearts and new futures.

Central to their vision of human flourishing in God’s renewed world, then, was the prophets’ announcement that a number of things that can survive in this world will not be able to survive in the world to come.

Like war.

Rape.

Greed.

Injustice.

Violence.

Pride.

Division.

Exploitation.

Disgrace.

Their description of life in the age to come is both thrilling and unnerving at the same time. For the earth to be free of anything destructive or damaging, certain things have to be banished. Decisions have to be made. Judgments have to be rendered. And so they spoke of a cleansing, purging, decisive day when God would make those judgments. They called this day the “day of the LORD.”

The day when God says “ENOUGH!” to anything that threatens the peace (shalom is the Hebrew word), harmony, and health that God intends for the world.

God says no to injustice.

God says, “Never again” to the oppressors who prey on the weak and vulnerable.

God declares a ban on weapons.

It’s important to remember this the next time we hear people say they can’t believe in a “God of judgment.”

Yes, they can.

Often, we can think of little else.

Every oil spill,

every report of another woman sexually assaulted,

every news report that another political leader has silenced the opposition through torture, imprisonment, and execution,

every time we see someone stepped on by an institution or corporation more interested in profit than people,

every time we stumble upon one more instance of the human heart gone wrong,

we shake our fist and cry out,

“Will somebody please do something about this?”

We crave judgment,

we long for it,

we thirst for it.

Bring it,

unleash it,

as the prophet Amos says,

“Let justice roll on like a river” (chap. 5).

Same with the word “anger.” When we hear people saying they can’t believe in a God who gets angry—yes, they can. How should God react to a child being forced into prostitution? How should God feel about a country starving while warlords hoard the food supply? What kind of God wouldn’t get angry at a financial scheme that robs thousands of people of their life savings?

And that is the promise of the prophets in the age to come:

God acts.

Decisively.

On behalf of everybody

who’s ever been stepped on by the machine,

exploited,

abused,

forgotten,

or mistreated.

God puts an end to it.

God says, “Enough.”

Of course, to celebrate this, anticipate this, and find ourselves thrilled by this promise of the world made right brings with it the haunting thought that we each know what lurks in our own heart—

our role in corrupting this world,

the litany of ways in which our own sins have contributed to the heartbreak we’re surrounded by,

all those times we hardened our heart and kept right on walking,

ignoring the cry of someone in need.

And so in the midst of prophets’ announcements about God’s judgment we also find promises about mercy and grace.

Isaiah quotes God, saying, “Come, . . . though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow” (chap. 1).

Justice and mercy hold hands,

they kiss,

they belong together in the age to come,

an age that is complex, earthy, participatory, and free from all death, destruction, and despair.

When we talk about heaven, then, or eternal life, or the afterlife—any of that—it’s important that we begin with the categories and claims that people were familiar with in Jesus’s first-century Jewish world. They did not talk about a future life somewhere else, because they anticipated a coming day when the world would be restored, renewed, and redeemed and there would be peace on earth.

So when the man asks Jesus how he can get eternal life, Jesus is not surprised or caught off guard by the man’s question, because this was one of the most important things people were talking about in Jesus’s day.

How do you make sure you’ll be a part of the new thing God is going to do? How do you best become the kind of person whom God could entrust with significant responsibility in the age to come?

The standard answer was: live the commandments. God has shown you how to live. Live that way. The more you become a person of peace and justice and worship and generosity, the more actively you participate now in ordering and working to bring about God’s kind of world, the more ready you will be to assume an even greater role in the age to come.

But Jesus is aware that something is wrong with the man. Rich people were rare at that time, so there is good reason to believe that Jesus knew something about him and his reputation. Jesus mentions five, not six, of the commandments about relationship with others. He leaves out the last command, which prohibited coveting. To covet is to crave what someone else has. Coveting is the disease of always wanting more, and it’s rooted in a profound dissatisfaction with the life God has given you. Coveting is what happens when you aren’t at peace.

The man says he’s kept all of the commandments that Jesus mentions, but Jesus hasn’t mentioned the one about coveting. Jesus then tells him to sell his possessions and give the money to the poor, which Jesus doesn’t tell other people, because it’s not an issue for them. It is, for this man. The man is greedy—and greed has no place in the world to come. He hasn’t learned yet that he has a sacred calling to use his wealth to move creation forward. How can God give him more responsibility and resources in the age to come, when he hasn’t handled well what he’s been given in this age?

Jesus promises him that if he can do it, if he can trust God to liberate him from his greed, he’ll have “treasure in heaven.”

The man can’t do it, and so he walks away.

Jesus takes the man’s question about his life then and makes it about the kind of life he’s living now. Jesus drags the future into the present, promising the man that there will be treasure in heaven for him if he can do it. All of which raises the question: What does Jesus mean when he uses that word “heaven”?

___________________

First, there was tremendous respect in the culture that Jesus lived in for the name of God—so much so that many wouldn’t even say it. That is true to this day. I occasionally receive e-mails and letters from people who spell the name “G-d.” In Jesus’s day, one of the ways that people got around actually saying the name of God was to substitute the word “heaven” for the word “God.” Jesus often referred to the “kingdom of heaven,” and he tells stories about people “sinning against heaven.” “Heaven” in these cases is simply another way of saying “God.”

Second, Jesus consistently affirmed heaven as a real place, space, and dimension of God’s creation, where God’s will and only God’s will is done. Heaven is that realm where things are as God intends them to be.

On earth, lots of wills are done.

Yours, mine, and many others.

And so, at present, heaven and earth are not one.

What Jesus taught,

what the prophets taught,

what all of Jewish tradition pointed to

and what Jesus lived in anticipation of,

was the day when earth and heaven would be one.

The day when God’s will would be done on earth

as it is now done in heaven.

The day when earth and heaven will be the same place.

This is the story of the Bible.

This is the story Jesus lived and told.

As it’s written at the end of the Bible in Revelation 21: “God’s dwelling place is now among the people.”

Life in the age to come.

This is why Jesus tells the man that if he sells his possessions, he’ll have rewards in heaven. Rewards are a dynamic rather than a static reality. Many people think of heaven, and they picture mansions (a word nowhere in the Bible’s descriptions of heaven) and Ferraris and literal streets of gold, as if the best God can come up with is Beverly Hills in the sky. Tax-free, of course, and without the smog.

But those are static images—fixed, flat, unchanging. A car is a car is a car; same with a mansion. They are the same, day after day after day, give or take a bit of wear and tear.

There’s even a phrase about doing a good deed. People will say that it earns you “another star in your crown.”

(By the way, when the writer John in the book of Revelation gets a current glimpse of the heavens, one detail he mentions about crowns is that people are taking them off [chap. 4]. Apparently, in the unvarnished presence of the divine a lot of things that we consider significant turn out to be, much like wearing a crown, quite absurd.)

But a crown, much like a mansion or a car, is a possession. There’s nothing wrong with possessions; it’s just that they have value to us only when we use them, engage them, and enjoy them. They’re nouns that mean something only in conjunction with verbs.

That’s why wealth is so dangerous: if you’re not careful you can easily end up with a garage full of nouns.

In the Genesis poem that begins the Bible, life is a pulsing, progressing, evolving, dynamic reality in which tomorrow will not be a repeat of today, because things are, at the most fundamental level of existence, going somewhere.

When Jesus tells the man that there are rewards for him, he’s promising the man that receiving the peace of God now, finding gratitude for what he does have, and sharing it with those who need it will create in him all the more capacity for joy in the world to come.