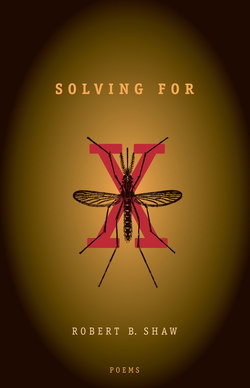

Читать книгу Solving for X - Robert B. Shaw - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Future Perfect

It will be recognizable: your neighborhood,

with of course some of the bigger trees

gone for pulp and the more upscale houses

sporting new riot-proof fencing which

they seem hardly to need in this calm sector

whose lawns look even more vacuumed than they used to.

Only a soft whirr of electric automobiles

ruffles unburdened air. Your own house looks

about the same, except for the solar panels.

Inside, the latest occupants sit facing

the wall-size liquid crystal flat TV screen

they haggle and commune with, ordering beach towels

or stockings, or instructing their stockbrokers,

while in the kitchen dinner cooks itself.

Why marvel over windows that flip at a touch

from clear to opaque, or carpets that a lifetime

of scuffs will never stain? This all was destined,

down to the newest model ultrasound toothbrush.

Only the stubborn, ordinary ratio

of sadness to happiness seems immune to progress,

and it will take more time than even you

have at your disposal to find out why.

The same and not the same, this venue fascinates,

spiriting you through closed familiar doors

on random unremarkable evenings when

you will have been gone

for how long? — Just a bit longer than your successors

have had to make these premises their own.

However much their climate-controlled rooms

glow vibrant with halogen, they will not see you.

But they may wonder why, for no clear reason,

they find their thoughts so often drawn to the past.

Back Again

The wormy apple tree

we chainsawed to a stump

is not content to be

a barren amputee.

It has produced a clump

of rank and spindly shoots,

a thicket still unthinned,

each one a witch’s wand,

suggesting that the roots

regard our surgery

as one more hostile thing

to overcome in spring,

like parried blades of wind —

mischief to live beyond.

A Bowl of Stone Fruit

Never forget the child’s face, nonplused

on touching first an apple, then a pear,

then a banana, his bewildered stare

becoming peevish as his buoyant trust

in the appearances that grown-ups prize

founders. Items for which his taste buds lusted

are for display, and regularly dusted.

Try to explain how people feast their eyes

on such a centerpiece, how they are able

to cherish a quartz peach, whose blushing skin

is bonded pigment, stone bearing within

no stone a tree would spring from. Now the table

stands taller than his head; but watch him grow,

to grow unflustered by the cold and hard

baubles adult taste holds in fond regard.

Never forget his face, first made to know.

Airs and Graces

All this was years ago — back in the days

of afternoon visits between ladies

with children brought along, resigned to boredom.

Her mother always stayed for a second cup;

her mother’s aunt, happy to be a hostess,

kept pressing macaroons on her niece

and grand-niece (something neither of them favored).

It always seemed to be raining when they went there

and there was no dog or cat to play with.

When the women were tired of glancing sideways

to see her fidgeting or shedding crumbs,

they’d send her to the spare room to explore

the Dress-Up Box. This could be interesting

if she was in the mood for vintage glamour.

The Box was really a modest-sized tin trunk,

lined with flowered wallpaper and filled

with bits of swank from several decades back.

There were a few dresses, much too large,

trimmed with velvet and imbued with camphor.

It was the accessories she was drawn to.

There was a pair of white gloves that on her

were almost elbow-length. The missing buttons

forced her to bunch them at her wrists, so that

she looked like a Walt Disney character.

There were various paper-and-bamboo fans

with orchids and pagodas painted on them.

She fanned her face with these and made her bangs flap.

What else? A pin made of a real seashell,

a set of tortoise-shell combs, a rhinestone bracelet.

More intriguing: an oblong of black lace,

a shawl or a mantilla, that she always

spread out before her eyes while she decided

just how to drape it. Looking through its fine,

close-knotted mesh gave her a view like one

she could have got through a sooty window screen.

Two or three hats with feathers of no color

she’d ever seen on a bird sat carefully nested.

Best of all, always to be admired,

there was a brown, weaselly-looking fur piece,

that ringed her neck and dangled down her front,

the eyes studding its narrow nut of a head

inky black and hard as rock, the nose

rubbery-feeling like an old eraser.

A little chain could cinch the snout and tail

together, but the fixed jaws wouldn’t bite.

There, in the little stuffy almost-attic,

trying these in their different combinations

before a mirror, practicing to be old

and regal, she could lose track of the time.

She grew oblivious to the parlor voices

talking about people she’d never known.

Finally, when her appearance satisfied her,

she paced grandly down, the funeral veil

swathing her hair, the spineless animal

bobbling to her waist. Her mother gasped

and clapped her hands. Her great-aunt smiled briefly,

then looked into her teacup. Years would pass

before the festooned girl would realize what

her hostess must have seen: her bygone self

and her dead sisters, flaunting these fine items

when they were new, and later not so new.

The First Mosquito

Still warm, still damp. Twilight.

Emboldened to impinge,

the whining parasite

administers a twinge,

a punctual siphoning

announcing summer’s prime.

Too small to call a sting,

the lump she left this time

vouches for blood she needed

to spawn what will in turn

go forth to do as she did.

We might as well adjourn —

indoors. With skin awoken

to June so pointedly,

we’ll settle for one token

of such phlebotomy.

A Field of Goldenrod

Midas, your fabled gleaming touch

would be hard put to burnish much

that ocher crop across the road —

like some erupting mother lode,

proliferating uncontrolled

back to the treeline, solid gold.

In truth, I doubt you could enhance

one August field’s extravagance

by any glitter you could lend.

This is the wealth of summer’s end;

an alchemy within the weed

will flaunt itself to scatter seed,

and summer, in a mood to splurge,

will outdo any thaumaturge.

Anthology Piece

Why, I sometimes wonder, out of all

the spirited conceptions of my Maker,

am I the chosen one? Reprinted ceaselessly,

misprinted sometimes (I have had death appear

in place of dearth, and yes, there is a difference),

memorized by the multitude — why me?

Something in my unmistakable rhythm

seems to have taken readers by the ear;

or could it be my undemanding scenery,

dusty road pointing ahead to sunset?

Woven snugly together with accustomed

sentiments toward all that’s transitory . . .

What could be simpler? By this time I might

be sick of it myself, were I not bound

to bless my access to eternity.

As for the man who set my sky ablaze,

he grew to loathe my popular appeal,

but of course wasn’t able to disown me.

Once I was plumper: seven lines, some good,

didn’t survive the last slash of his pen.

(You’d never know: he didn’t save the drafts.)

Now I am all that keeps his name alive,

pressed by hundreds of pages front and back.

Saffron pyres flicker on my horizon.

He’d have pissed on the embers if he could.

The End of the Sonnet

A word was missing from his fourteenth line.

He mused on how much easier it would be

if one could still wedge an apostrophe

in “over,” or if cattle still were kine,

when he was yanked away from his design:

his daughter’s kitten, too far up a tree,

had to be rescued. Undelightedly

he undertook to grapple with white pine,

up in whose jutting plumes of needles clung

that tiny fright incarnate and enfurred.

He got it down. His daughter’s satisfaction

was ample, quick, and real. His forearm stung

with scratches, but his brain hummed with a word

found on a high branch, fathered by distraction.

Dec. 23

He’s finished tacking up the Christmas garland

so it arrays the Parish Hall at one end,

loops of glistering tinsel off a rafter.

Nagged by Sunday School teachers, none of whom

could reach to do it, he brought up his ladder

and hammered through their bicker of suggestions

to pin the swags the way he damn well wanted.

Under this job tomorrow an eight-year-old

boy, a seven-year-old girl will cradle

a large, diapered baby doll between them,

while shepherds of the same age, some of them

notorious brats, stand burlap-clad with canes,