Читать книгу Norman Clyde - Robert C. Pavlik - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

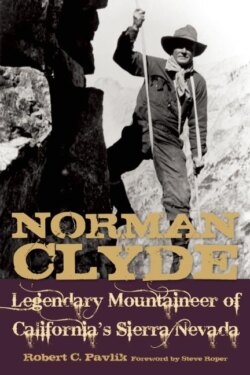

ОглавлениеForeword by Steve Roper

Years fly by. Decades come and go but mostly go. Our collective memories of former peers and heroes thus get more and more lost with each new generation. Thankfully, biographies exist to keep certain people “alive.” Norman Clyde is perhaps not well known to the youths of today, except as a mere name associated with California’s High Sierra. But Robert Pavlik has done an admirable job in bringing to light Clyde’s extraordinary life. The word “unique” is often used inappropriately, but after you read this book I would wager that you can’t think of a better word for this prodigious individual. In an obituary for Clyde in 1973, his friend Tom Jukes captured the essence of the man in a few words: “[He] had lived as every alpinist wants to live, but as none of them dare to do….When he died, I felt that an endangered species had become extinct….He was large, solitary, taciturn, and irritable—like the North Palisade in a thunderstorm, and he could also be mellow and friendly, like the afternoon sun on Evolution Lake.”

Clyde’s name was familiar to all Sierra mountaineers in my youth. You couldn’t turn a page of Hervey Voge’s 1954 book, A Climber’s Guide to the High Sierra, without a reference to a Clyde first ascent. I exaggerate slightly, for the master spent much of his time in the central Sierra, or its south, mostly ignoring the Yosemite region, perhaps too tame for him. Most striking of all in Voge’s guidebook was the fact that so many of Clyde’s ascents were done solo, this in an age when few people roamed the High Sierra, no rescues were possible, and a broken leg away from a popular trail meant an agonizing death. No search-and-rescue teams, no helicopters, no cell phones. A different age, one that Pavlik captures beautifully.

Virtually every solo mountaineer today claims that the inner struggle is what makes the endeavor worthwhile—the overcoming of deep-set fears with no one to turn to for advice or help. In our hectic life today we are so rarely alone that going solo elicits comments about a person’s sanity. Clyde did jokingly refer to his mental health in a letter to an acquaintance in 1925: “I sometimes think I climbed enough peaks this summer to render me a candidate for a padded cell—at least some people look at the matter in that way.” But one gets the impression from this book that Clyde was simply a run-of-the-mill loner, undoubtedly with a few repressed demons lurking about, but not a man who tried to sway anyone with his solitary exploits. To him, being alone must have been business as usual.

Aside from Clyde’s remarkable first-ascent record, what most captivated me back in the 1960s about the already legendary man was the size of his backpack, described with awe by older campfire raconteurs who had actually seen and hefted these monster loads. Though I was impressed that a human could traipse so casually around the high country with a pack that weighed eighty pounds, I was puzzled by some of the reported contents. An axe? A revolver? Hardback books? Hardback books in Greek? A cast-iron frying pan? This was in the days when we all were “going light,” a phrase that a decade earlier had been the partial title of an influential Sierra Club primer. Hearing such stories, I thought Clyde must have been a man from an earlier century, perhaps even an alien. And, in a sense, he was. Surely he must have been appalled, near the end of his life, to see bearded hippies with scantily clad girlfriends strolling casually through the High Sierra with twenty-five-pound packs containing a simple aluminum pot, plastic utensils, huge bags of granola, and near-weightless copies of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha.

I thought I knew much about Norman Clyde’s life and times, the “times” being when the High Sierra were, paradoxically, both explored and unexplored. Late in life Clyde stated that he had been most active in that interlude between the pioneers—1860 to 1910—and the technical rock climbers, who arrived in the 1930s to scale the “impossible” cliffs. Reading Pavlik, I discovered new insights. For instance, Clyde was well aware that by 1920 excellent maps existed, that the range was well known, and that most of the highest peaks had been climbed. But “minor” unclimbed peaks—like the exquisite Mt. Huxley and the craggy Deerhorn Mountain—were among the most startling formations of the High Sierra. And Clyde sought these out. A forty-year-old kid let loose in a candy store! As Clyde himself admitted, he was not a great technical climber. He seemed content to seek out beautiful or remote peaks with relatively easy routes and often reported later, in his typical laconic manner, “No sign of previous ascent.”

Much though I admired Clyde’s mountain skills, I was not a fan of his prose, as Pavlik points out in this book. I thought my hero’s words were dry and impersonal, and I still feel this way. Yet I was unaware that he wrote such a phenomenal amount. I now picture him at his typewriter on a snowy winter’s day, alone as usual, pecking away, probably with two fingers, thinking of new ways to describe his sublime but rather limited universe.

Clyde’s personal life was certainly unsettled. Everyone knew that he could be a curmudgeon and occasionally act rude. I met him only once, in a setting he must have hated: a sporting-goods store in Berkeley where I think he was trying to cadge equipment. I was young and timid and hardly said a word; it was enough to simply gaze upon this aging legend. He certainly behaved himself on this brief encounter, but Pavlik has a lot to say about his behavior elsewhere, and this is what makes the book so intriguing. Clyde was no saint and could be downright antisocial at times. With fairness and respect, Pavlik, having done an enormous amount of research over fifteen years, delves into all aspects of Clyde’s life.

If Clyde was occasionally cantankerous, he could also be generous. Everyone familiar with High Sierra history knows how Clyde persevered, by himself, in the Minaret Range in 1933, looking for the body ofWalter Starr, Jr., long after the other searchers had given up. And I knew of one or two other of his efforts in this regard. Pavlik has discovered, in ancient newspapers and by contacting peripheral people, that Clyde was involved in numerous other unpleasant but necessary searches to locate an overdue hiker or climber. He seems to have had a preternatural ability to know where a missing person would go and how he or she might act. His astonishing knowledge of the natural world helped, so he was quick to see a fresh rockfall scar, for instance, or hear buzzing flies that might indicate a nearby corpse. Clyde was certainly the outstanding human tracker of the High Sierra for many decades.

But Clyde was not simply a California superman, and Pavlik eloquently describes his feats in other regions. Many Sierra aficionados might be unaware of his travels outside the state. An example: Clyde’s adventures in Glacier National Park in a matter of weeks during the summer of 1923 are almost unbelievable. In this book you will learn of his endurance and route-finding abilities as he ascended Montana peaks far more complex and dangerous than those in his beloved Sierra. At the time, probably no one in the world was attacking mountains at such a demanding pace. More significantly, this was not some reckless, hotshot kid bent on fame; he was a careful, thirty-eight-year-old climber. Norman Clyde was, without question, a unique individual.