Читать книгу The Road to San Donato - Robert Cocuzzo - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 7

ОглавлениеEveryone in their life has his own particular way of expressing life’s purpose—the lawyer his eloquence, the painter his palette, and the man of letters his pen from which the quick words of his story flow. I have my bicycle.

—Gino Bartali

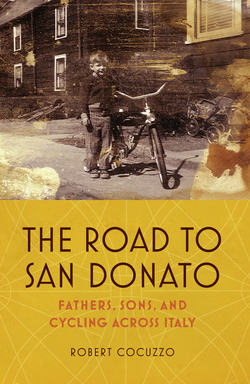

When I was growing up, a bicycle represented absolute freedom to me. From as early as I can remember, my buddies and I cruised around our neighborhood like a rowdy pack of stray dogs. We pedaled up into the woods by the old water tower, where we could find empty beer bottles to chuck against the rocks. Or sometimes, if we were really lucky, we’d come across an old waterlogged nudie magazine. My oh my, what joys these two wheels could bring a curious kid!

We were totally reckless. Helmets were for “losahs.” We screamed down steep hills in my neighborhood, egging each other on not to touch our brakes, as we raced toward busy intersections to beat a red light. One time, my buddy Dooley blasted right through oncoming traffic while chasing me and my best friend, Wally. In my memory two cars spun out like in the movies as Dooley miraculously threaded the needle. We didn’t even stop. We kept on pedaling, laughing hysterically and buzzing with that same intoxicating adrenaline we got from pelting a police car with a snowball.

We obsessed about our bikes, squirrelling away money from raking leaves and shoveling snow to buy shocks, disk brakes, mag-rim wheels, clip-less pedals, and (if we were really going for broke) a full-suspension frame. When it came to bikes, the major difference between me and my friends was that when I went home, the obsession didn’t end—my father stoked it. Dad gave me my first fixed-gear bicycle after I graduated college. Gleaming black and yellow, the aluminum-framed Schwinn was a thing of beauty. Dad had his mechanic switch out its traditional drop handlebars to a pair of bullhorns wrapped in camo tape. He had the back brake stripped off, so the rear wheel slid through the frame freely.

“But you have to keep the front brake,” he told me.

“Why? You don’t have a front brake.”

“Your mother would kill me,” he said. “Plus, you got more to protect up there.” He tapped his head.

“Fine, but I’m not going to use it.”

He smirked. “We’ll see about that.”

Dad took me on fixie rides through the city. We’d rip up tight alleys, jockey through traffic, and chase down every cyclist we saw. From the first pedal stroke, I fell madly in love with the raw torque of a fixed gear. The bike came alive, forcing my feet to spin faster and faster. If I tried to coast, the pedals launched my knees violently into my chest. The all-or-nothingness of the fixed gear drew me into its devoted tribe.

Drafting off my Dad’s back wheel, I marveled at how easy he made pedaling a fixie look. Every one of his pedal strokes had a purpose. Like a boxer throwing jabs, hooks, and uppercuts, he pedaled combinations of force to move methodically. He read the traffic, calling out cars that were about to stop or turn into our lanes before their signals blinked. His hands pointed out potholes, sand, glass, and other tire-popping perils. I had always assumed he was reckless on his bike, but here I witnessed just how much control he had.