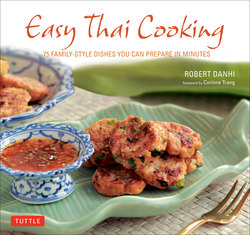

Читать книгу Easy Thai Cooking - Robert Danhi - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеStocking Your Thai Pantry

My goal in this chapter is to demystify the ingredients used within this book. Enabling you to find these building blocks of flavor at your local grocer or order them online. Once you know what to look for, discover how they are commonly used, and learn the basics for storage you are well on your way to creating the authentic flavors of Thailand in your kitchen.

The following pages will lead you through the basic ingredients, however, the quality and overall flavor variation between different growers, manufacturers, importers, and distributors is enormous, so knowing what to look for is essential in finding the most appropriate ingredient. Cooking the foods of Southeast Asia for the past two decades I have discovered, tasted, experimented with and, sometimes, discarded thousands of things. What was once my favorite brand is replaced by another one years later and other items, like rice powder already roasted and ground, I could not find even five years ago is now in most markets I frequent. It is an evolving landscape and is why I created chefdanhi.com, to constantly keep you informed of the latest and greatest building blocks of Thai flavor. There are links there for finding your closest market stocked with Asian ingredients.

Stocking your kitchen puts you in control and only a few items need to be bought fresh. Storing these building blocks of flavor in your pantry, refrigerator, and freezer allowing you to whip up a meal at a moment’s notice. The freezer will extend the shelf life of some key ingredients. Buy and store some of these items for when you are in need. Some things such as banana leaves, lime leaves, chilies, shrimp, minced lemongrass can be bought and immediately stored in the freezer. The same goes for seeds, nuts, fried shallots, garlic, and dried shrimp.

Sometimes I like to get ahead and prepare some things before freezing. Peeled galangal and ginger hold up well, I simply grate them when frozen or slice a few pieces as needed. I even have minced lemongrass in bulk, and spread onto a baking sheet to freeze (freeze in small particles) then gather up into a bag or container so I can scoop them out and cook later—about 1 tablespoon minced lemongrass per stalk. If I have extra fresh squeezed lime juice, I portion into small containers, or an ice cube tray, freeze and pull out what I need. If you want to make your own curry pastes, look to my Southeast Asian Flavors book for the recipes, you can make the paste and freeze in portions for later reference.

In Thailand, most condiments and spice pastes are stored at room temperature, however they often consume these items more quickly than Westerners. Hence, storing some items in the refrigerator makes them last longer. Chili sauces, curry pastes, seafood condiments (fish sauce, oyster sauce), and tamarind paste can be chilled for maximum quality retention.

Fresh vegetables, fruits, herbs, meat, and seafood must be bought when you need them. Getting to know your local store’s staff will surely help you glean the most select cuts of meat, fresh fish, and produce. Take the time to establish these relationships and you will be rewarded with the things you need to create truly delicious Thai flavors. I sometimes even bring samples of the food I make—keeping the staff happy means they will look out for quality ingredients for my Thai meal.

Asian Greens It almost pains me to group such a diverse family of vegetables into one category. The various deep green versions of bok choy, choy sum, water spinach, or flowering broccoli of the brassica family can be used in the recipes, use your judgment pairing heartier greens with bold flavored recipes. Firm, perky leaves and stems without any discoloration on the cut stem side are sure signs of freshness. Keep these covered to avoid wilting from dehydration.

Bean Sprouts Made from sprouting the small green mung beans. Fastidious cooks pick off the straggly ends one by one, leaving the sweetest pearly, white crunchy small stalks for adding texture to salads, noodle bowls and stir-fries. Avoid brown, wilted, or slimily wet sprouts. Handle them gently and keep them in an air tight bag or container for a couple of days.

Chilies The Thai people’s passion and copious use of chilies is profound. The recipes in this book primarily use two chilies: the intensely spicy small Thai chili and the more mild, yet still hot, finger-length red chilies. These chilies are pounded, sliced thinly, minced, crushed or left whole for a gentle infusion. The capsaicin compound responsible for the spice is primarily located in the veins, seeds are guilty by close association and the rest of the chili has some heat (see “Working with Chilies,” page 25). They should be firm, dark green to red and not shriveled and black. The best substitute is frozen Thai chilies, available in freezer section or just freeze fresh ones when available. You can substitute with Serrano. For the finger-length red chilies you could use jalapenos but I prefer the ripe red Fresno chilies.

Dried Chilies When chilies are dried their taste evolves since the drying process is slow they slightly ferment and concentrate, and achieve a deep red color. Water soaked chilies are often pounded or ground into spice pastes, marinades, and dressings. Also found on the table as a condiment, the dried chilies are roasted and ground. They can also be quickly fried whole and used as a spicy and crispy edible accompaniments to a variety of salads and other dishes.

Chili Paste in Soya Bean Oil (Nahm Prik Pow) Flavorful concoction of deep roasted-slightly sweet flavor comes from fried garlic and shallots, chilies, and dried shrimp. Palm sugar and tamarind balance the flavor and crates this multi-purpose sauce used in many of the recipes in this book. The base of a quick hot and sour soup (see Hot and Sour Tamarind Soup, page 56), component of a glaze (Grilled Chicken Wings with Tangy Chili Glaze, page 46), or simply spread on bread with a few slices of cucumber as a snack this is one of my favorite ingredients. This complex sauce is not easily duplicated and this ingredient tends to hold a pivotal role in the recipes it resides in. If a store-bought product cannot be found, you can make it yourself (see Thai Chili Jam, page 36). Once a container is open it keep in the refrigerator for months.

Cinnamon (Cassia) The dried bark of two varieties of trees, is infused in savory stews and broths and is part of the famous Chinese five spice used throughout Asia. The thicker bark, known as cassia is most common in Asia, yet the thinner type is acceptable in smaller amounts. Rather than grinding to a powder, it is common to use whole strips to infuse a soup or sauce. The two different types of this spice do not need to be labeled differently so follow the aforementioned visual clues and try to find the thicker cassia at an Asian market or online.

Coriander Leaves (Cilantro) The leafy green herb from which the coriander seed is produced has an amazing flavor all its own. Possessing a lemony, floral aroma and sharp tartness on the palate. As the most widely used herb in Southeast Asia all parts of this plant are very useful. The leaves and tender stems are usually chopped together, the seeds are used as a spice (Coriander Beef, Page 69), and roots have an earthy flavor used in most curry pastes and many marinades.

Coriander Seeds These seeds emerge from the top of the coriander (cilantro) plant at maturity. Their strong earthy and lemon-like flavor is ground into spice pastes. Toast seeds until slightly darkened, let cool, then, if need be, grind. There is no substitute, you might want to try to use fresh coriander leaves (cilantro).

Fresh Coconuts Coconuts change as they mature, young green-skinned ones are packed with juice (referred to as coconut water) and the flesh is soft and gelatinous. The older they get the thicker, and firmer and rich with fat that provides coconut milk, a pillar of Thai cooking. Cracking open a coconut requires a few swift swings of a large knife. Buying fresh coconuts can be challenging, many stores have inventory that sit for a long time and go sour, so seek out a reliable supplier. Young coconut juice/water can be bought canned, actually some brands are quite tasty. The frozen plastic containers have the best flavor and still somewhat silky flesh. Mature coconut should be heavy with juice, give a shake to feel for this and listen.

Coconut Milk and Cream Decadent white liquid with a hint of sweetness and velvetly smooth texture. Made by taking the shredded hard white flesh of mature coconuts, blended with water and squeezed to yield opulent creamy fluid. Coconut cream on the other hand is traditionally made by squeezing the shredded meat without water, then the water is added for a second extract on coconut milk. To learn more about making your own fresh coconut milk look in Southeast Asian Flavors or chefdanhi.com. Coconut milk is used as a foundation for savory curries, to enrich soups and sauces and create decadent sweet treats.

Canned or boxed coconut milk is pasteurized, often homogenized and sometimes stabilized; making the milk thicker than hand-made. To keep it simple this book was developed using all canned/boxed milk.

Squeezing the shredded meat without water traditionally makes coconut cream, then the water is added for a second extract on coconut milk. Used to begin Thai curries (see pages 28–29), for coconut toppings and custards and other places the rich satisfying cream is appropriate. Coconut milk should have about 15–23% fat content. Coconut cream contains about 24% fat.

Eggplant There are dozens of varieties commonly used in Asia, in Thailand some common varieties include the round (1½–2 inch /4–5 cm) diameter variegated green orbs, or the long slender purple Chinese/Japanese varieties. The variegated green are used raw to scoop up spicy chili dips or simmered in green curries, where as the longer eggplants are usually cooked. Firm fleshed, smooth skin with firm stems should be present. Store loosely covered in the refrigerator.

Fried Garlic and Shallots These two favorite flavor boosters have become staples in kitchens across all of Southeast Asia. Although browned garlic and shallots can be created as the first stage of cooking a recipe, these crispy versions are used at the last moment, adding a crunch, a rich flavor and appealing look. You can make your own (see Fried Garlic, page 37 and Fried Shallots page 37). Bags, jars or plastic containers are available—the quality varies greatly. I look for those that only list shallot or garlic and oil, those with palm oil tend to have the best crunch and overall flavor. Avoid those that have flour or other starches included. They keep for months in the freezer or even the refrigerator where I keep a jar with a shake top for quick reference. They can be left at room temperature for weeks, I use my home made versions at room temperature. If they are store-bought, I store them frozen and defrost when needed.

Fish Sauce This salty, pungent, and essential seasoning has an amber color, and substantial umami impact, rounding out a lot of flavorful Thai foods. It is often the major sodium source in Thai food. Cooking a majority of real Thai food for vegetarians is a challenge since fish sauce is used so often, I turn to light soy sauce or low-sodium soy sauce and begin with the same amount. If you don’t use it often you may want to keep in your refrigerator to slow down the aging process. Sometimes sodium crystals form in the bottle over extended times, no need to worry, proceed on!

Galangal (blue ginger) (Kha) Much tougher than ginger, the readily apparent lines around its circumference of the thin skin encompasses a mustard-camphor like citrusy aroma. I like to keep them loosely wrapped in the refrigerator. If they are hard for you to find (or order online), peel and freeze a large piece (you can find it in many freezer sections at markets also). When in need, grate it frozen so you can measure them easily or slice off a few pieces. Dried powder or slices have no flavor, better to use nothing or substitute with ginger.

Green Papaya Actually an immature, not just unripe papaya, is firm and really not that flavorful, it’s a textural experience and a medium for seasonings. Look for smooth green skins without wrinkles. The surface should be very firm, almost hard. Store loosely covered or in a drawer in the refrigerator.

Kaffir Lime Leaves and Zest This aromatic branch of the citrus family tree is prized mostly for its pungent leaves. The wrinkly fruit has a wonderfully strong scented zest used in spice pastes but the juice of the fruit is almost never used. Leaves are steeped whole in broths and curries, fried quickly to a crisp for snacks or garnish. Look for the uniquely double lobed sturdy leaves that are shiny and dark green on one side and a matte light green on the other. For every 6 lime leaves I use 1 teaspoon lime zest, usually added towards the end of the recipe. Best when fresh, useless when dried. They freeze quite well, make sure to keep them airtight and only pull out those needed for each recipe.

Lemongrass These sturdy slender stalks are an icon for Thai food. It has a crisp citrus aroma that perfumes Thai dishes at all ends of the spectrum from cool salads to fiery hot curries. Most commonly, the bottom 4–6 inches (10–15 cm) are used for infusing, mincing, or slicing very thinly to shorten the tough fibers that run lengthwise. The outer tougher leaves must be stripped away, revealing the aromatic and tender inside. As a substitute I would suggest ½ teaspoon lemon zest with ¼ teaspoon lime zest for each stalk of lemongrass. Better yet, buy frozen already chopped lemongrass or buy fresh stalks when available and freeze them for future use. Keep them, wrapped loosely, in the refrigerator for a week or two.

Limes Limes and all citrus are indigenous to the Asian continent. There are a variety of limes used in Thai cuisine including the largest Persian lime or common lime, small “key” lime, knobby kaffir lime, and the perfumed kalamansi lime. This book only utilizes the most common limes. In Thai cuisine, the juice is commonly used in uncooked recipes for dressing and as a final tableside garnish, the flavor does not hold up well under heat or over time, so juice your limes as you need them. Never buy bottled lime juice. The zest is grated when the aroma of the lime is what you want, the oils contain most of the precious aroma. Look for bright or dark green limes that are firm to the touch without any brown or soft spots. They can be kept room temperature for a few days, but I keep them loosely covered in the refrigerator.

Long Beans (Yard Beans) Heartier than standard green beans these earthy tasting beans are 1–2 feet long (about ½ meter). Snacked on raw as part of a table salad to accompany salads and rice dishes or cooked, these are flavorsome beans. I prefer the deep green variety. The stem end should not be dried out and shriveled. Store covered loosely in the refrigerator.

Mint (Peppermint) Mint’s unique ability to produce a refreshing cooling sensation gives it a star role in the Southeast Asia. It may pack a wallop of flavor yet extensive exposure to heat kills its flavor so it’s usually eaten raw or added at the very last moment. There are two primary varieties: peppermint (more commonly used), which has wrinkled leaves and hard woody stems; while spearmint has smooth darker green leaves and soft edible stems and has a more assertive bite—same as Thai basil.

Noodles, Dried Flat Rice Probably the most popular noodle in Thailand, these noodles come in many sizes, as thin as ¹⁄8 inch (3 mm) and as wide as ¾ inch

(2 cm). Transform these noodles into soups and stir-fried dishes. Soak for

30 minutes in room temperature water before a quick boil. More often than not dried noodles will be labeled with the Vietnamese “Banh Pho.” Store at room temperature, sealed air tight—almost indefinitely.

Dried Rice Vermicelli Noodles (Rice Sticks) The thinnest of all rice noodles, they have a subtle flavor and delicate texture. In Thailand there is one special variety known as Khanom Jin—the batter is slightly fermented before making noodles. Salads, noodle bowls, soups, and stir-fried dishes all welcome these firm threads that act as flavor carriers. I prefer to soak them in water first, then boiled to cook for the best texture. I look for ingredient statements that list only rice and water (maybe salt). Recently some manufacturers have been adding tapioca starch, making them more durable but creating a different texture.

Fresh Flat Rice Noodles The Chinese invented the technique of making a thin batter of ground rice or rice flour batter that’s steamed into sheets then cut into various widths. Once refrigerated they get brittle, so buy them, take them home, and pull into individual noodles, then gather up and refrigerate in portions. They are often sold on a shelf in a non-refrigerated section of the market. Look for markets that have daily deliveries of these supple ribbons. It’s okay to buy at room temperature and use that same day, then keep in the refrigerator for up to a week, they are vastly superior on the first day.

Dried Bean Thread Noodles (Cellophane Noodles, Glass Noodles) Skinny, transparent noodles made from the starch of mung beans. Little flavor to speak of but with a resilient texture. They are used in salads, soups, and spring rolls. Simply cooked by covering dried noodles in boiling water for about 5 minutes and then draining.

Oyster Sauce This Asian food essential was invented in China in 1888 by Lee Kum Kee, in one of history’s finest accidents. A pot of oyster stew was forgotten, it boiled down into this enchantingly heady nectar. Now used across Asia, this culinary powerhouse is deep brown with hues of gold and has a potent salty, slightly sweet, seafood flavor. Flavor from oyster extract, slightly sweet with sugar, seasoned with salt, and thickened with starch, it has the unique ability to not only season, but tenderize marinated meats and seafood. It also can give a distinctive sheen to sauces and glazed items. The more oyster extractives the better—higher priced bottles are often an indication of this desirable quality trait. For those with diets that exclude oysters, look for “vegetarian oyster or stir-fry sauce” that can be used as a substitute, using equal amounts.

Pandanus leaves Long slender deep green leaves contain the most charming aroma due to the natural presence of 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline. Any green sweet in Thailand is bound to be colored and aromatically infused with this special herb. There is no substitute, vanilla added to a recipe that calls for pandanus may taste good but will not taste Thai. I buy fresh when it’s available, and freeze some when I get home or I buy frozen leaves. Always trim the lighter colored bottom portion (it tastes like dirt). Keep fresh, wrapped tightly in the refrigerator for a few days, frozen they keep for months.

Peppercorns True peppercorns created the primary spicy sensation across Asia before chilies arrived in the 15th century. The same plant is processed into three colors: green peppercorns are picked immature and usually pickled; black are produced by fermenting and drying green ones; white are soaked, husked, and sun dried. Whole black pepper-corns can be used to infuse; coarsely crushed they add bursts of fiery bites; white pepper is generally ground finest, added to spice pastes or added at the very end of cooking. Green peppercorns are usually used whole. Thai cooks use each colored peppercorn separately and don’t buy mixtures. Green ones are rarely found fresh outside of Asia. I buy them brined in salted water (avoid vinegar). Black and white are both sold dried. Look for plump, somewhat evenly colored white and evenly shaped shriveled black peppercorns.

Peanuts (Groundnuts) An icon for Southeast Asian cuisine, peanuts are included on all parts of the menu. Creamy peanut sauce, pan-roasted, crushed, and tossed into noodles or transformed into a sweet filling for a sweet snack, the peanut’s versatility is unmatched. Roasting your own peanuts has its flavorful rewards. Slowly pan roasting or a quick deep-frying are best. Some shelled peanuts still have the skin attached, they are delicious if not a bit messy to peel so you may want to get peeled raw nuts and roast them yourself. If you do choose to save time by buying them pre-roasted then make sure they are unsalted and un-seasoned. Keep in the freezer to extend their life to 6 months.

Pork Fat This is a common cooking ingredient. The flavor elements it contributes and the texture it creates is unmatched. Thais like to deep-fry, pan-fry, or stir-fry in rendered pork fat. You can buy what is labeled as lard—a somewhat neutral flavored pork fat. It does have more flavor and a thicker mouth feel than vegetable oil and, for some stir-fries, I like this.

Jasmine Rice Uniquely aromatic rice naturally contains aromatic compound called 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline. Commonly called steamed rice by mistake it is cooked by covering with water and bringing it to a boil. Jasmine rice that’s grown in Thailand is government authorized to be labeled as Thai Ho Mali, it is quite special. This species, however, is grown around the globe, even in California, with great results.

Sticky Rice A long grain rice packed with a unique starch structure that gives the cooked rice a firm and elastic texture. A staple of northern Thailand, usually soaked then steamed. Used in sweets, toasted and ground as a flavorful thickener and used to scoop up sauce and salads. Look for the stark long-grain white rice often labeled as glutinous or sweet rice. There is no true substitute, regular long grain rice can be served as a side instead. Store at room temperature, sealed air tight—almost indefinitely.

Salt In the USA, most cooks and chefs prefer kosher salt. Most sea salt is also not overly processed, and available globally, so that is another salt you can use. The size of the grain actually can make a significant difference in measuring salt. Since salt is not used too much in the book (sodium is usually added in the form of fish sauce, soy sauce, or ready-made condiments) and in small amount it won’t make much of a difference. Start with less and add more as needed. If you only have iodized fine table salt reduce the amount by half, taste, and adjust from there.

Soy Sauce Dried soy beans are soaked, cooked, and inoculated with special mold and fermented for months, during this process the proteins are naturally broken down to free glutamate and increase in savory flavor—the same thing that happens with fish sauce. Soy sauce is used less frequently than fish sauce but similarly. Used to add a depth of flavor by adding sodium and its unique taste. Each soy sauce, like wine, can be made from the same primary ingredient, yet can taste drastically different. Look for naturally “brewed,” actually a term used to designate that this was fermented during an extended aging process giving it a rich flavor and dark color. Do not buy brands that contain caramel coloring (except for dark soy sauce where caramel coloring is acceptable).

Sriracha Sauce Invented in its namesake town of Sriracha, Thailand, a southern seaport village just North of Pattaya, this traditionally fermented chili sauce was originally a table condiment, but its popularity has made it into the ingredient list of many modern dishes. Mostly chilies, garlic, vinegar, sugar, salt, and vinegar. I have used it as a primary seasoning in salads and noodles. There are many different brands of this beloved condiment each with its own style. Other fine pureed chili sauces from places like Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam may work but a taste test is the only real gauge. Once a container is open it keeps in the refrigerator for months.

Star Anise Shaped like an eight-pointed star, hence the name, the flavor of black licorice or fennel. A key ingredient of Chinese five spices. This spice is steeped in aromatic stews and soups as well as ground into a variety of spice blends and pastes. Make sure to remove it before serving a dish (one bite is a definite turn off).

Stocks and Broths Stocks are made primarily of bones while broths include meat. General purpose Asian style stocks are more subtle than their western cousins of the same name because they are not made with the traditional combination of bones, carrot, onion, celery, and aromatics. Usually they just have bones, meat, or shells and a couple of aromatics infused in simmering water. Chicken, pork, shrimp, fish, and beef stocks are also utilized in Thai cuisine. These form the basis of many Thai soups and help add moisture to stir-fried dishes. Canned or boxed broths or stocks can be substituted with decent result. I actually suggest adding some water (up to an equal amount) to create a neutral flavored all-purpose stock. Let taste be your guide. Look for reduced sodium labels as they allow for better control of seasoning. If you make a fresh stock, cool it quickly and store in refrigerator for about a week. It’s best to freeze it for longer storage, up to a few months is fine. Canned or boxed items can be stored at room temperature, once opened, transfer to new container and store in the refrigerator for about a week.

Sweetened Condensed Milk A luxurious milk creation, pearly white and strikingly sweet (45% sugar) it is rich, viscous, and delicious. Created in the late 1800’s by concentrating fresh milk and adding loads of sugar. The not-so-secret, yet ever so magical sweetener calms the intense Thai Iced Coffee (page 114). I find it is also very handy to enrich sweets, such as the Grilled Bananas with Sesame Seeds (page 108). Beware of less expensive cans labeled as “Sweetened Condensed Filled Milk” as they are cut with hydrogenated vegetable fat. Nothing compares or can be substituted. Evaporated milk is used for Thai tea and is similarly concentrated, yet no sugar is added. Once opened, transfer to a new container, cover, and store in the refrigerator for up to a few weeks.

Sweet Soy Sauce Much darker, thicker, and sweeter than regular soy sauce with a flavor similar to salty molasses. Used in meat marinades as a tenderizing flavor enhancer and seasoning element. Some Thai brands are labeled as Thai Sweet Sauce. An acceptable substitute is the thicker Indonesian Kecap Manis.

Tamarind Concentrate Large fruit pods, filled with a deep brown, sticky, tart-n-sweet paste hang from trees. (To make your own paste go to page 25.) The paste is processed into blocks that are sold to be diluted with water to form a pulp. However, for convenience, you can find ready-made concentrates. All recipes in this book can be made with the concentrate. Soups are soured, sauces are balanced, glazes are thickened and drinks are made refreshing with tamarind. Look for ingredient labels with a short ingredient list with tamarind listed first. Although sodium is not listed on the ingredient statement, they can be salty, containing around 3% sodium. The paste can be stored at room temperature, the pre-made concentrate must be stored in refrigerator once opened. The paste lasts for more than 6 months, an open concentrate will last for a month.

Thai Basil (Asian Basil) Probably the most common herb in Thai cooking, it’s easily recognized by its smooth pointed leaves attached to a purple stem. The flavor is similar to common basil with scents of anise and cinnamon. It is used as a raw garnish as well as added at the end (in copious amounts) wilting and reserving the color and perfuming the entire dish. Curries, soups and salads all welcome its flavor. The anise-like aroma that these possess is tough to duplicate, if Thai basil can’t be found, simply use equivalent amounts of the common basil. Sometimes I add a small pinch of finely ground star anise or anise. Look for unblemished leaves that are firm and deep green. Fresh herbs are very perishable—heat, physical abuse, and moisture need to be managed. I have found that gently and loosely wrapping the bunch in paper towels then placing in seal bag and storing in the refrigerator keeps them fresh the longest—up to a week.

Thai Curry Pastes Wet spice pastes are created by grinding aromatics, such as fresh coriander leaves (cilantro), lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime leaves, garlic, and shallots. Also roasted and pulverized spices like coriander, cumin, and peppercorns are traditionally pounded in stone mortars with a pestle. Electric powered mechanical devices such as blenders and food processors are now commonly used. Curry pastes are rarely used raw, they are most often fried in coconut oil. Recently I have been experimenting using the typical red, green, yellow, mussaman, penang curry pastes that I make or buy already prepared in non traditional recipes. The Crunchy Sweet Papaya Pickles (page 42) dish is a result of this. Most stores stock curry pastes on the dry goods shelves in bags, plastic tubs, or cans. Once a container is open it keeps in the refrigerator for months.

Thai Palm Sugar (Coconut Sugar) Golden brown to light tan in color and sweet like granulated sugar with a hint of caramel. Made by boiling the sap of a palm tree (sometimes a coconut palm) down to a syrup, then crystallized into a sugar. Not only is it sweet, it really has a notable flavor, used to sweeten and enhance a dish, sweet or savory. Formed into disks, ranging from 2–6 inch (5–30 cm) or packed in plastic containers. Pay close attention to the color as there are several varieties of palm sugar distinguishable only by flavor and color. Thai style (as is Vietnamese) palm sugar is light brown whereas palm sugar from Malaysia or Indonesia is dark brown and should not be used as a substitute. Light brown sugar is the best substitute. Keep in an airtight container at room temperature. When you bring some home from the market, use a hand grater or set up your food processor with grating/ shredding attachment and grate all the sugar, store in a covered plastic container and scoop it out when you need it.

Tofu (Bean Curd) Entire books are and should be dedicated to the vast array of soybean protein based tofu. In Thailand they use most major varieties of tofu, such as curd, silken, sheets, and fried. This books uses silken tofu that is gelatinized soy milk, making it silky smooth. Silken tofu is sold in aseptic-boxes—no refrigeration is needed and curd tofu is sold fresh, basking in water. Once fresh tofu is opened it needs to be used within a few days.

Thai Sweet Chili Sauce Hailing from the northern region of Issan, and traditionally served with Gai Yaang (a spice marinated grilled chicken) its sweet syrupy texture is speckled with chili flakes and garlic yielding a mostly sweet and slightly sour mildly spicy sauce. It’s commonly used as a dipping sauce straight from the bottle. It’s easy to make your own (see Thai Sweet Chili Sauce, page 35). If I buy it, I usually fortify it with some chopped coriander leaves (cilantro), minced ginger, and add a touch of fish sauce or soy sauce to calm the sweetness. I also like using it to glaze grilled ribs (see Sweet-n-Spicy Pork Ribs, page 47). Once a container is open it keeps in the refrigerator for months.

Turmeric Powder The dried rhizome that is ground into a fine powder. utilized primarily for its bright orange-yellow color rather than its subdued almost chalky taste. This spice imparts its color to just about anything, including fingers (some people wear gloves when handling turmeric). It is used to tint curries, marinated meats, and even tofu throughout the region (Grilled Tofu Curry, page 85). Purchase turmeric in its powder form as the dried whole rhizomes are hard to use and have no real benefit to them. Fresh turmeric is becoming more common and it has a different taste and strength. For every 1 teaspoon of dried I use 1 tablespoon (½ oz/14 g) of fresh grated.

Yellow Bean Sauce (Yellow Bean Paste, Brown Bean Sauce) Deep brown in color, this thick salty paste is made from ground and fermented soybeans. Packing a sodium and umami laden punch it provides a depth of flavor. Fermented and salted yellow soy beans can be chopped or mashed. This flavorful paste is a byproduct of soy sauce production. Store in the refrigerator for up to a couple of months.