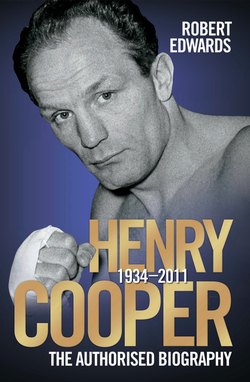

Читать книгу Henry Cooper - The Authorised Biography - Robert Edwards - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеThere can be very few sportsmen whose career and reputation mark them out as instantly recognizable to a public outside their sport but there is one figure whose extraordinary popularity, by virtue of the traits he exhibits, marks him out as belonging to that select band, the ‘national treasures’. He is Henry Cooper.

Before television, such figures were rare; they would be seen on newsreels, perhaps heard on the radio, and we would read of them in the press, but the advent of mass visual broadcasting allowed them an audience that would have been unheard-of even a few years before. The development of satellite broadcasting multiplied their audiences again by many times, and so as the 1950s gave way to the next decade, sports were considered to be a global activity, and participants had to be of a global standard. If they were not, they would fall by the wayside, and indeed many, particularly boxers, went the way of musical hall comedians. A sportsman’s character became important, too, as a mass audience could be quick to spot a personality who did not seem to deliver a certain character with which they were comfortable. It is different today, of course – Mike Tyson still has a huge following, despite his obvious character traits.

Henry Cooper survived the transition from private parochialism to public globalism. His fans spanned Europe and America once he had proved that he was a world-class heavyweight. He did this in 1958 when he beat the formidable Zora Folley, then ranked second in the world, behind the great Floyd Patterson.

And Henry’s personality shone through: relaxed, modest, realistic and hugely skilled. At the time he won the British and Common wealth heavyweight title in 1959, he was still living with his parents on an equally modest council estate in southeast London, sharing a room with his twin brother, George. He only moved out when he married in 1960. Unsurprisingly, George went, too.

As he rose to prominence (and stayed there), the nation came to identify with him. On the occasion of his first encounter with Cassius Clay in 1963 in a world title eliminator, when he put the American on the canvas, the country was heartbroken when he lost the fight. That he lost it by chicanery was clear, but he said nothing. When, on the occasion of his last fight against Joe Bugner in 1971 he lost through what can be only described as suspicious refereeing, Britain was doubly saddened, as the event triggered his retirement. In between, when he fought Muhammad Ali for the world title in 1966, it was a more important sporting occasion to many, particularly this author, than the World Cup Final of the same year.

All in all, Henry Cooper fought 55 professional bouts as a heavyweight; he won 40, lost 14 and drew one. He successfully defended his British and Commonwealth title a record number of times and won three Lonsdale belts while doing it. That he had to sell these a few years ago in order to meet his liabilities as a Lloyd’s name touched the nation as deeply as anything that had happened to him professionally.

His post-retirement career kept him in the public eye like no other man; he seemed ageless. But time moved on; there were things he could say that he could only hint at in the past. The woes that befell him as a Lloyd’s underwriter are, while well known, still something of a mystery which we can explore, as one venerable British institution is cynically ripped off by another.

I first started discussing this project with Sir Henry after the publication of my biography of Stirling Moss; in many ways Sir Stirling brokered the introduction as the pair were not only good friends but also shared a manager for certain events. Stirling is also a boxing fan. Although I had met Henry (very briefly) at a boxing evening some years before, I had no real acquaintance with him whatsoever, so when the familiar figure strolled into the London Golf Club in Sevenoaks, Kent, which was our agreed rendezvous, and simply shoved out a huge hand in greeting, I confess to being quite charmed.

Such was the demeanour of the man that the prospect of working with him on this project was, professionally as well as personally, a compelling one. As he leaned forward to explain some of the niceties of professional boxing (as opposed to mere violence) I realized that he was probably one of the most articulate and relaxed men I had ever met. The difference between the amateur and the professional, expressed in terms of career, was fascinating, as was his description of the 1963 Clay fight, which he famously lost. The rigours of the training camp, the dirty tricks of the ring, all was there, expressed lucidly, honestly and with the assurance that only a man with a career such as his could offer.

Some of the bad guys of the period are interesting, too, particularly now that many of them are dead, and we can breathe more easily. With so much money about, we should not be too surprised at the people we find lurking in the shadows – we meet the odd gangster, some truly terrifying businessmen and promoters, as well as a host of fighters, many of them obscure and forgotten now, but in their day, men who struck fear into a prudent heart. There are boxers Henry wished he could have fought (Joe Louis, his childhood inspiration), there are boxers he was glad he managed to avoid (Rocky Marciano, Sonny Liston) and those he knew he could beat (Cassius Clay). There are men he wished he could have hurt more (Piero Tomasoni) and those, particularly the three who knocked him out (Patterson, Johansson, and Folley) all of whom he recalled he rather liked. Being knocked out, he assured me, is entirely painless if an expert such as Patterson does it.

The sociology of boxing in these years 1954-1971 is interesting. The double life that he unavoidably led, living on a council estate while lunching in the West End as British heavyweight champion, was one with which he dealt very well indeed, and I have the impression that if he had to start again, he would have changed very little about himself. He did regret that his twin brother, George, did not progress further as a boxer, but George had recurrent fitness difficulties that frankly held him back. The pair made a good team at fights, though, with George acting more or less as Henry’s trainer when he himself retired. There is some suspicion that of the two men George might have been a touch more aggressive when their paths were parallel, not out of sibling rivalry, but merely temperament. Interestingly, although the pair were identical, they were ‘symmetrical’ or ‘mirror’ twins – Henry was left-handed, George right. They lived a few miles from each other in Kent and were always close.

Henry and George enjoyed a unique relationship with manager Jim Wicks that was brokered by a journalist after the brothers had finished their National Service with the 4th Battalion, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, in 1954. They had both fought in the Army as amateurs and turned professional under Wicks as soon as they were released. Wicks was a totally honest but deceptively hard man, who managed the twins’ careers with great integrity. This is not always the case, as critics of the sport are quick to point out. The Wicks/Cooper relationship was very much in loco parentis. It was also the envy of fighters managed by lesser men, and there were plenty of those.

Wicks had started out life as a bookmaker and progressed to man agement rather as a second career. He was a heavy gambler and, by all accounts, a successful one. His headquarters, the gym above the Thomas à Becket pub in the Old Kent Road became, under his management, a mecca for British boxing and something of a social hub for the fans of the sport. Celebrities made sure they were seen there, watching the fighters train. All very gladiatorial.

Henry was quite straightforward as to motivation: he fought because it was his business to fight and not for reasons of some misty-eyed sentimentality. Wicks identified this and as a result theirs was a strong partnership. Boxing is a brutally Darwinian sport and there is a professional ‘sudden death’ element to it. A fighter who is over-matched and loses serially will stand little chance of recovering in order to take on worthier opponents. Conversely, a fighter who is constantly under-matched, fighting relative midgets and achieving a series of easy victories will not be considered a draw by promoters. It is a fine balance and Wicks found it; Henry was British champion for longer than any other man.

Awareness of boxing is deep in our collective psyche, whether we follow it, or approve of it, or not. The very terminology, the lexicon of boxing, is all around us and we use it quite unconsciously every day: ‘coming up to scratch’, ‘throwing in the towel’, ‘making a fair fist’, ‘out for the count’, ‘saved by the bell’, ‘on the ropes’ and so on.

This book is not intended to be a history of the prize ring, and not only because I am not particularly qualified to write that book. I am not, unlike others, steeped in the history of boxing, but I do regard its traditions as being of great significance to my story, as I saw in Henry Cooper a man who had inherited the mantle of so many men in the past, champions of Britain, or at least England, whose popularity at the time was very similar to that enjoyed by him now.

The evolution from accomplished sportsman to national treasure is not an easy process to follow; one day we find that it has simply happened. In Britain, it is not always a status conferred purely by statistical success, either. There is a further quality that is required – that of character, as if the British believe that only the man who has so little to prove can be acceptably humble, and not in a Uriah Heep sense, either. Many men who achieved a great deal less than Henry did are far from that, of course, and are as a result far less popular and sought after.

Boxers can have something of an uphill struggle in this particular, purely because of the nature of their sport. It is not one that many understand (indeed, many people even refuse to accept even that it is a sport), save that it has a very dark side to it. It can be difficult to reconcile what our popular boxers such as Henry Cooper actually did for a living with the fact that we also like them so much; for they do and did what the vast majority of us simply cannot conceive of doing: climbing into a ring with another man, under formal and old-established rules, and beating him, fair and square, with frequently bloody results.

The association of the observer with what is actually happening in a boxing ring is quite unlike other sports. Many feel that they could drive a Grand Prix car, or manage their way around a golf course with some credit, or even serve an ace at a major tennis tournament (and they are probably wrong in all those assumptions) but climb into a ring with Ingemar Johansson, or even Brian London? No; it would be quite unthinkable.

Given the very shadowy nature of boxing, particularly when Sir Henry Cooper was Britain’s senior exponent of it, his public started to identify with the simple fact that his involvement in it seemed to have left him morally untouched, unlike, perhaps, Sonny Liston, who while he was a tremendous hero to some, would probably not have included the late Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother among his fans.

Some sportsmen are so competitive, so aggressive, that their state borders on that of a kind of autism. The public realizes this and often feels distanced, even repelled, as a result. I have met racing drivers, for example, who have never won a race, nor even achieved a podium position, but some of them have exhibited such a swaggering self-regard that I feared – not much, I must confess – for their sanity. I have never met a boxer like this; to be sure, there are those who rise to a certain tongue-in-cheek level of performance, but the suggestion is always there that this is so close to self-parody as to be considered an entertainment: merely perhaps, the hobby of easily bored men. The boxer’s pride is generally a quiet thing, and we like and admire them for that.

No one who reads this book will be remotely surprised when I say that I like boxing rather a lot. It is an interesting sport and I admire what fighters do very much. The fact that it has been, literally and metaphorically, ‘on its back foot’ for some time is a matter of great regret to me. I have also had a go at it myself; in the 1960s, when I was at school, it was considered morally compulsory to lace on the huge, ancient and iron-hard ‘mauleys’ (around the back of the bike sheds, usually) and square up in some grotesque and ill-supervised mismatch. I got soundly thumped, of course, and it hurt, rather a lot, as I recall. There is nothing quite like a good whack in the solar plexus before Latin to quite put you right off the subject. So, my admiration for most of the men who do this for a living knows few bounds.

Although I well remember so many of Henry’s fights, it has been interesting for me to cross-refer to so many contemporary accounts of them from more seasoned observers than me who were at the ringside. By and large, but not exclusively, I have used broadsheet and specialist press coverage, for the simple reason that it is generally well written and concise, and lacks that ghastly sentimentality that seems to infest the tabloid world, although the opinion of that most accomplished writer, Peter Wilson of the Daily Mirror, is always illuminating. Similarly, the veteran observer Harry Carpenter’s insightful pieces, which he wrote so well for the Daily Mail, have been invaluable.

Viewing contemporary footage of some of Henry’s encounters has also been revealing, if only because the flawed nature of some of my own recollections are revealed, but it is important to stress that the perspective of television or video is strictly two-dimensional and can be highly misleading; the view of a boxing match offered by being seated near the ringside is far removed from that offered by being seated on a sofa and watching from a distance, if only because the spectator at a live match can see (and hear) how hard these men actually hit each other. Television denies us this.

Interestingly, even broadsheet coverage differed radically in its reportage of a given fight, even down to the details of times elapsed and relative points. This is not necessarily for reasons of professional sloppiness, merely an aspect of history. No two writers will ever see things in exactly the same way, which is why it is important to compare and contrast consistently. After reading the bulk of the broadsheet press, it seemed to me that the Daily Telegraph’s Donald Saunders and The Times’s Neil Allen seem to have been the most consistent, particularly in their pre-match assessments, which are a useful litmus test of the informed opinion of the day.

It is not, of course, for me to make light of the efforts of any of the men in this book, no matter how they engaged with their subject, Henry Cooper. No man who boxed at this level for a living deserves anything but the total respect of any writer on the subject. Thus in drawing conclusions as to the relative abilities of certain fighters – putting them into context – I have relied either on Henry, the informed press, or what I think to be a workable consensus of contemporary opinion. But one thing I have learned is that statistics are seldom the measure of any man.

For this aspect of sport is important: sportsmen operate strictly in their own context. We cannot evaluate any sportsman on an absolute basis, although we are always trying to do it, for the simple reason that conditions, most obviously the quality of opposition, are such a huge historical variable. With motor racing, or any sport that depends upon technology as much as nerve to take it forward, a driver can only be measured in his own time and this crucial aspect applies even to other more individual sports, such as mountaineering. What could Edward Whymper have accomplished with modern equipment? Boxing, however, is more fundamental, more basic. A fight staged sixty years ago, or even a hundred, would be quite recognizable now, and Tom Cribb would no doubt certainly appreciate the skills of Henry Cooper; whereas I cannot imagine what that brave driver Christian Lautenschlager would make of a modern Grand Prix car; he would probably love it, once it had been explained to him what it actually was.

The years fall away, and I stand face to face with Sir Henry Cooper in his drawing room, deep in rural Kent. Patiently, he is demonstrating to me why it is that southpaws are so difficult to fight; why it is that they should all be ‘strangled at birth’, as he only semi-humorously puts it. In fact, I can see his point exactly. Southpaws, for a boxer of Henry’s polarity, are clearly very hard to hit properly if you engage with them conventionally and can be counted inconvenient at best, but when he switches to a regular stance and we are engaged normally, almost as if for a waltz, I glance down and see that huge, waiting left fist, its biggest knuckle almost the size and texture of a damaged golf ball. I realize that it is less than a foot away from my chin and that if that was what we were about, he could hit me before I could even consider blinking. I even know through which wall of his house I would probably travel. It is sobering. I begin to realize what the game is really about and hope that his well-honed instincts do not kick in; basically, I hope he likes me. A little homework has already revealed to me that it is this fist, which delivered the finest punch of its kind for a generation, could accelerate faster than a Saturn V rocket at full chat and, after travelling such a short distance, would connect with an impact of over four tons per square inch; the physics involved are quite ridiculous. I glance up at him, bathed in the light of final comprehension. The famous Cooper grin is followed by what I perceive to be a quick, knowing nod. He knows I understand. No words are really necessary.

What is startling, I suppose, is the sheer intimacy which two fighters must share; there must be constant, 100 per cent eye contact, as Henry put it: ‘It’s all in the eyes; you can tell everything from the eyes. If a man is going to throw a punch, he telegraphs it with his eyes, and if you’ve hurt him, you just know it by looking at him.’

Boxing is a sport driven by opportunity and is, perhaps more than any other sporting activity, a real mirror of life. The toe-to-toe opportunism of the fight itself, echoed by the deft opportunism of the promoters (and in some cases the managers) produces a rich cultural stew, which invites sampling with a very large spoon indeed. There have been many tragedies in the fight game – boxers who died in the ring – Benny Paret, beaten to death by Emile Griffith; Johnny Owen, who lingered six weeks in a coma before succumbing to the assault he had received from Lupe Pintor, and Jimmy Garcia, who died in 1995 following a brutal fight with Gabriel Ruelas. Then, of course, Gerald McClennan and Michael Watson, both damaged badly, McClennan sadly beyond repair. Also, consider the other casualties – Randolph Turpin and Freddie Mills, both suicides – not to mention so many others, their dreams of glory shattered as they died before their time in lonely rented rooms, unremembered. But I am afraid I still love it, or at least I love the idea of it.

There are not many fighters whose reputations grow after they retire. I can think of Jack Dempsey, Max Schmeling, Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali and Henry Cooper. All, bar Henry, were world champions, but that is not the point. When a genuinely confused Max Baer asked, after Henry had entered the rankings in 1958, ‘Tell me, doesn’t that guy ever get mean?’ he meant it quite seriously. Baer, a playboy by his own confession, was world heavyweight champion for 364 days after dropping the giant Primo Carnera and he simply could not understand why Henry Cooper seemed so placid.

There is a powerful lobby that argues that boxing is primarily a matter of economics and Henry Cooper was actually one of them. There is a very ancient joke, which I suspect re-emerges from generation to generation, of the landed earl, who, while riding the bounds of his estate, discovers a trespassing vagrant, taking his ease in the shade of a tree:

‘What are you doing on my land?’ cries the toff.

‘Who says it’s your land?’ responds the tramp.

‘Well, I inherited it.’

‘From whom?’

‘From my father’

And where did he get it?’

‘From his father.’

Well, it all goes further back in similar fashion to some era near the third crusade:

And where did he get it?’

‘Well, he fought for it, actually.’

‘Right, you bugger,’ says the tramp, taking off his tattered coat, ‘I’ll fight you for it now’

So, who are we to deny Sonny Liston, from his shoeless and unlettered childhood, his fine house in Las Vegas?

Henry Cooper occupies a unique and enviable place in the contemporary British consciousness. The clear contrast between his public (and private) nature and the often grim business of prizefighting does not sit uncomfortably with anyone, even those who admired him as a man but detested what he did for a living – and there are, it must be said, many of those.

The sheer inaccessibility of boxing rather defines it to most people; one can stage a pro-celebrity event in most sports after all, except these martial arts. It is sometimes tempting to suggest it, of course, and many of us might imagine that Mike Tyson vs Paul Daniels would be an entertaining event to watch, but that simple reality, that boxing is actually about hurting people, sometimes very badly, and sometimes with quite disastrous results, makes many turn away from it. How can one like a man who does this for a living? Quite easily, in fact.

So, Henry Cooper was different. Different also from other fighters in terms of the perception with which he has long been regarded. Those who admired Henry, what he did, what he became, are a different group perhaps from those who admire Chris Eubank, although to a fighter, all are one – as intelligent men (and boxers by and large are highly intelligent, they have to be) they share both a living and a vast mutual respect and seldom really despise each other, whatever they may say in public.

His reputation is undimmed. For his fans, knowledgeable or not, he remains the man who asked Muhammad Ali, then called Cassius Clay, some questions to which the American (who seems now to be a global treasure) did not necessarily have a ready answer. To others, those whose interests occupy purely the British sport, he was the holder of no fewer than three Lonsdale belts, a record that cannot ever be beaten under current regulations, and when Henry was forced to sell them, the nation felt deeply for him, for they knew him to be a man who had started off in life with few material possessions, that these treasures, going under the hammer (or ’ammer, I suppose) at an obscure country auction, these trophies were objects for which he had fought, won for himself, literally taken with his own hands. He had not been born to them. This sorry spectacle was not that of some dissolute chinless wonder selling off his unearned and mortgaged inheritance, rather there was something almost biblical about it.

But boxing audiences are also more fickle and more merciless than the wider public. It is almost impossible to believe it now, but on the evening of 5 December 1961, over 40 years ago, Henry Cooper, the man we revere so much now, was actually booed out of Wembley Arena after being dropped by a carthorse kick of a right from that same Zora Folley whom he had outpointed three years before. As one commentator, Robert Daley of the New York Times, put it sympathetically at the time: ‘Mercifully, he was probably too dazed to notice.’ How times change…

In his professional career Henry Cooper fought 44 men on 55 separate occasions. He won 40 fights (27 of them inside the distance), drew one and lost the other 14. These are mere numbers, of course, but they make up, by my calculation, 371 rounds, or 18½ hours of competition (and punishment) at the highest level. Like many fighters, he would have been willing to do more, but unlike so many who sadly did just that, he came through the process completely unaltered.

But that is surely what boxing is about. It is a bilateral interrogation. How fast, strong, clever or brave? What have you got in there? It lifts a very few men to heights of confidence quite unknown to most and the majority of fighters thus remain forgotten. Henry Cooper had been retired from boxing for over 30 years before his death in 2011, but he will not, I submit, be forgotten, because he quite simply survived the process. For this he thanked the quality of his management, for which read Jim Wicks, that avuncular but perhaps slightly sinister maestro from Bermondsey. The relationship between these two men was an exemplar of trust and understanding that is rare in any human activity, let alone sport, and well-nigh unique in boxing.

That he survived so well, and that he demonstrated this so regularly by being such a public figure (and a knight, to boot) was the cause of much appreciation, both public and private. When I set out to explore the life of this professional fighter – this prizefighter, I did so with the knowledge that Henry’s personal appeal cut across anything so trivial as social class or, even more importantly, whether or not the Cooper fan is even a fan of the sport at which he excelled. No, it is simpler than that. People love Henry Cooper because he came unscathed through a process that would quite terrify any imaginative person. He put himself in harm’s way and came out on the far side of that quite unspoiled and clearly uncorrupted by a sport and a business that, by the time of his retirement, was becoming a byword for sleaze, a cipher for corruption. One can describe Sonny Liston (or Mike Tyson, for that matter) as a truly terrifying man, but that adjective comes nowhere near doing justice to some of those men who handled them and ran and damaged or destroyed their lives.

The British sport was not, of course, quite as grimy as its American counterpart, mainly because of a more monolithic regime of regulation. The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBC) has had many criticisms fired at it, and indeed many of them are entirely justified, and it is an organization that certainly has its detractors now, but it is true to say, no irony intended, that by and large they made a fair fist of it, however shabbily they occasionally treated Henry. Of course, they were up against rather less than the fragmented American regulators, who were often taking on (and occasionally in the pockets of) the Mob – seriously unpleasant people. The British underworld is happily a pallid and feeble thing by comparison with the likes of the Mafia; in the USA, there were truly dreadful men like Frankie Carbo – here, we had those dismal fantasists, the Krays. Enough said.

Boxing, for very good reasons, has always had a whiff of corruption about it, whether justified or not, but despite the distaste with which it is often regarded, for a multitude of reasons, people actually rather like boxers. There is no particular paradox to this, no inconsistency; it is, I maintain, quite obvious. In spite of the fact that many of Sir Henry’s fans would really rather prefer him to have done something else for a living, they also realize full well that if he had, he would simply not be the straightforward, proud man whom they admire so much. Henry Cooper, nice guy plasterer, is not the same thing at all as Sir Henry Cooper, KSG, OBE, – prizefighter. The man who beat Brian London to a confused and bloody pulp and broke the brave Gawie de Klerk’s jaw in two places before the fight was stopped is the very same man who also raised many, many millions for handicapped children and other good causes. That this fact may place the politically correct or the woolly-minded, bleeding-hearted liberal on the horns of a vast moral dilemma is, of course, less than dust to me – a mere rounding.

But it is interesting…