Читать книгу The Sailing Frigate - Robert Gardiner - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1: Prehistory

1600-1689

Over the centuries the term ‘frigate’ has carried a myriad of meanings, more often vague and suggestive rather than denoting a specific ship-type. The word itself is of Mediterranean provenance, and it is a reasonable assumption that the first vessels in northern Europe to be so described had the same origins: certainly, the first documented examples are privateers that operated out of the Spanish-held areas of the Netherlands as early as the 1590s. These were small, fast and lightly armed, characteristics that were to remain a common denominator of just about any ship called a ‘frigate’ whenever and wherever the description was applied.

To track the long and convoluted history of the term is more relevant to the lexicographer than the naval historian, and the aim of this book is to follow the evolution of a concept – a specialist cruising warship, not intended to fight in the line of battle but powerful enough for independent action in virtually every other naval role, in all weathers and on any ocean. These would encompass reconnaissance and other fleet support functions, both the attack and defence of trade, blockade and inshore operations, patrolling sea-lanes and suppressing piracy and smuggling. By the Nelson era the frigate had become the navy’s maid-of-all-work, the most flexible and broadly useful ship-type in the fleet and (with the exception of small craft) the most numerous category on the navy list.

SLR0368 On the basis of its decorative scheme this model is usually dated to just after 1660. ‘The Shearnes’ is painted on the upper counter, but there is no warship of that name, nor any built at Sheerness, that would fit. However, the model has the layout, proportions and, at 1/48th scale, roughly the dimensions of the first Parliamentary frigates, with the long heavily raked stem that was a feature of the time. The model carries a small poop and royalist decorations, but, like the full-size prototype, a model could be modified in the course of its life – and in 1660 republican symbolism was being removed throughout the country, from pub signs to warship names, to demonstrate loyalty to the newly restored King Charles II.

Note: The SLR number is the Museum’s unique object reference. As most of the models have no names, it has been used throughout this book for unambiguous identification. For the few models from Annapolis, the HHR number performs the same function.

It was not always so. In order to fulfil all these functions the frigate needed speed, seakeeping, manoeuvrability, structural strength, firepower and a large capacity (in order to stow sufficient provisions for long cruising range). This was a demanding set of requirements, many of which could only be realised at the expense of others, and all trumped by the over-riding need to hold down the size – and hence cost – of individual ships, to maximise the numbers that could be built and manned. All naval architecture involves compromise, but the large number of variables in frigate design offered a particular challenge, leading to greater variety and more radical evolution than exhibited by the battleships of the same period.

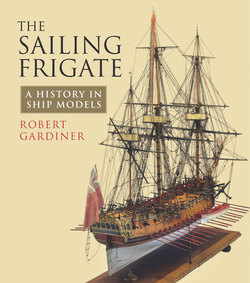

This book charts the complex and sometimes wayward search for a perfect sailing cruiser through the medium of ship models from the incomparable collection of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. Because they are three-dimensional objects, models make it easier to see exactly what these ships looked like, and the best of them incorporate significant detail that is absent from plans and impossible to discern in most drawings and paintings.

Frigates first came to the attention of the English, painfully, during the 1625-30 war with Spain when the Channel was said to be ‘infested’ with swift-sailing privateers from the Flemish ports under Spanish control. During this period it was estimated that they captured over 300 ships, perhaps one-fifth of the English merchant marine of that time. The king’s navy, a traditional battlefleet of powerful but unhandy ships, was ill equipped to deal with the menace, and never produced an effective counter. The most concerted effort was a numbered class of ten sail-and-oar pinnaces measuring between 160 and 180 tons called generically the Lion’s Whelps. They racked up some initial successes, but their performance deteriorated over time, probably because of the addition of heavier superstructure and more guns – the first example of a recurring theme in English cruiser design.

For all the concern with these ‘Dunkirk frigates’, the exact nature of their naval architecture was not at all clear at the time and has remained a mystery ever since. The term was applied to vessels from small sloops with a few guns to ships of 200–300 tons with anything up to 30 guns, so it is hardly surprising that a contemporary expert like Nathaniel Boteler could deny that they were a specific ship-type at all, reckoning them virtually indistinguishable from an English pinnace. However, in the descriptions of the time certain characteristics stand out: they were fast, with a low profile and very little superstructure, and so lightly built that their active careers might be as short as five years; and they could usually deploy oars to get themselves out of difficult situations. As the Duke of Buckingham, the Lord Admiral, expressed it, they were ‘as fit for flight as for fight’; and when they fled, nothing in his navy could catch them.

After the war the opportunity to study the type in detail was afforded by the arrest of two such vessels, the Nicodemus and Swan, whose crews were accused of piracy. The latter became the model for two vessels of around 120 tons, the Greyhound and Roebuck, built in 1637 to the king’s direct order by Phineas Pett; interestingly, while their designer referred to them as pinnaces, the king called them frigates. They were clearly not exact copies – another early manifestation of a recurring theme – because they were slower, but emphasised strength and seakeeping. When the Roebuck was sent to join the blockade of the ‘Barbary pirate’ base of Sallee in modern Morocco, the judgment was that ‘though she is not a good goer yet she is strong and able to endure any sea’. Two much larger vessels of over 300 tons, the Expedition and Providence, were also designed specifically for inshore operations off Sallee; these oared craft were rated as pinnaces, but in their high length-to-breadth ratio they shared one of the characteristics of the Dunkirk frigates.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642 most of Charles I’s navy sided with Parliament, but the country was faced with the repetition of a commerce war for which it was not prepared. The Royalists were unable to assemble a battlefleet but they did commission many privateers, including hiring some of the notorious Dunkirk frigates. This time the government, which needed the parliamentary support of the merchant classes, was quick to take action in defence of trade, and the first three of a new class of frigates were ordered in 1645. Adventure, Assurance and Nonsuch were 32-gun vessels of about 380 tons, possibly derived from the Expedition and Providence, which they resembled in proportions, although there was no mention of oars. As built they had eleven pairs of ports on the lower deck and a flush upper deck with five or six ports a side aft; at first there was no forecastle, so in layout they resembled some descriptions of the earlier Dunkirk frigates. However, it was soon found that they were too wet forward and in battle vulnerable to raking fire from ahead, so forecastles were added.

This is the earliest configuration of the frigate that it is possible to represent with a model. [SLR0368]

The evidence suggests that Parliament did not regard these ships specifically as cruisers, and in any case the follow-up ships were rapidly and radically modified. The outbreak of the first of three Anglo-Dutch wars spurred rapid improvements in the navy’s discipline, fighting tactics and ship design, and one of its principal lessons was deemed to be the battle-winning advantage of firepower. As a result, the frigates had their waists filled up with extra guns, becoming genuine two-deckers, and the Commonwealth’s naval administrators even developed much larger ‘great frigates’ that were the grandfathers of the eighteenth-century 74-gun ship. The Commonwealth frigate in its mature incarnation must have looked rather like model SLR0367.

SLR0367 Although damaged, this contemporary model is a valuable depiction of the overall appearance by the early years of the Restoration of a Fourth Rate or a large Fifth (there was a lot of reclassification between these rates in the 1660s). They were now full two-deckers, with a small poop. The ship maintains a feature of earlier frigates in the ability to deploy sweeps (there are eighteen oar ports a side on the lower deck). As ships grew larger this facility lost popularity, but as late as 1681 the Fourth Rate Tiger was rebuilt in this configuration and was referred to as a galley-frigate.

SLR0005 This Fourth Rate of about 1685 is typical of the kind of ship that performed many of the cruising duties under Charles II and James II. At the usual 1/48th scale it measures about 123ft by 34ft and may represent the 50-gun Sedgemoor of 1687 which, unusually for this rate, carried only 20 guns on the lower deck instead of the regular 22. At this period the flat transom of the so-called square-tuck stern would have been unusual, although there is evidence that the contemporary St Albans of the same rate had this feature.

Perhaps the greatest technical advance of the era of the Dutch wars was the emergence of organised fighting tactics. In the 1650s fleets still fought an essentially melee battle in which ships of all sizes could play a part, but the advantages of fighting in a line ahead formation soon became obvious as it made the best use of the firepower of ships whose guns were massed on the broadsides. The ‘line of battle’, as it was called, rapidly became the accepted disposition, and this in turn encouraged the concept of a ‘line of battle ship’ – ‘battleship’ for short – which could only be applied to ships powerful enough to take their place in the line. At first this extended down the fleet list to relatively small ships of around 40 guns (Fourth Rates) but, whatever their size, all these ships shared the same characteristics: multiple gun batteries on at least two complete decks and construction robust enough to withstand battering at close quarters.

Although the Dutch wars produced a ship optimised for fleet engagements, it did not inspire a specialist cruiser. There were ships too small to stand in the line, but they had very limited uses and were built in very restricted numbers. The smallest rating, the Sixth of around 14 guns or less, mainly performed inshore duties, to counter smugglers and local privateers; for example, the three ordered in 1651 were intended ‘to ply among the sands and flats to prevent pirates’. In many ways they were the ancestors of eighteenth-century sloops.

The larger Fifth Rates, armed in the 1650s with around 22 guns, grew in the following decades to carry around 32 guns. In layout they were originally reduced versions of the early Commonwealth frigates, with a single lower deck battery and a few guns aft on the upper deck, but in time they too acquired a forecastle and the larger of them became two-deckers when their waists were filled with guns, generally being rerated as Fourths. At a time when the largest merchant ships outgunned them, their value as warships was limited, and they were rarely deployed individually, although they did convoy escort work and joined squadrons on some of the less demanding stations. However, there was a design emphasis on sailing qualities, especially on manoeuvrability (‘nimble’ as it was expressed in the seventeenth century) and there was a specific reason for this. In fleet battles they had a role which was unique to that era: defending bigger ships from fireship attack and, conversely, clearing the way for their own fireships’ offensive.

Most of the roles that would fall to the eighteenth-century frigate were at this time performed by Fourth Rates. These small two-deckers were extremely useful ships, large enough to stand in the line of battle, but small enough to be built in relatively large numbers – and between the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution more than twice as many ships of this class were constructed than Fifth Rates. Outside the main battlefleet, they served in minor squadrons, provided the local ship of force on more remote stations, and were much involved in the attack and defence of trade.

Although Fourth Rates were built strong enough to survive a fleet action, their sailing qualities were not entirely ignored. Some (like SLR0005) had decidedly fine lines, and there is documentary evidence than many were considered fast, but as two-deckers their height of side would always hamper their performance to windward, making them less weatherly than sleeker ships. They were generally seaworthy and capable of long-distance deployments, but their lower gundeck ports were too close to the waterline to be opened in anything more than a moderate seaway, so they could not be regarded as all-weather cruisers. In truth, they were compromise warships that could perform most functions adequately but were not optimised for any one role – jacks of all trades but complete masters of none.

The invasion of 1688 which replaced King James II with William and Mary was called the Glorious Revolution, and it brought with it a revolution in foreign policy that in turn revolutionised the strategy and tactics of the sea war. England, after a generation of fighting the Dutch, was now co-opted into ‘Dutch William’s’ long-running conflict with France. This presented an entirely new challenge to the Royal Navy, and its administrators were aware that it would be a different kind of war from anything they had experienced previously. Among the first responses to this novel scenario was a programme of new Fifth Rates, to be built to a radical design concept proposed by Lord Torrington, the First Lord of the Admiralty. His specification, dating from June 1689, has a good claim to being the first conscious attempt to build a specialist cruising ship in the age of sail, and hence the first real frigate.

LORD TORRINGTON’S SPECIFICATION

This model is a unique contemporary depiction of the new Fifth Rates as originally conceived (with the requirements indicated in the original wording of the specification). As built, they varied in details – particularly in the number of ports on the lower deck, but the dimensions of the model are a perfect fit for the early ships of the class. They eventually mounted 32–36 guns, the main battery being sakers (6pdrs) with six, eight or occasionally more of the larger demi-culverins (9pdrs) on the lower deck, right forward and/or right aft where the sheer of the deck gave the ports most freeboard. Although the ports did not face directly forward or aft, they were originally described as chase guns, but in the right conditions they must have given the ships a little extra punch. Because of this partial lower deck armament, they are sometimes described by the French term demi-batterie.

HHR14 US Naval Academy Museum, Annapolis, Maryland