Читать книгу The Colour of the Night - Robert Hollingworth - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

THE NATIVE bushland was silent. At least it was to others: It is eerie, they would say, eerily quiet, like a vacuum. But it was no vacuum to Shaun Bellamy. Instead it was all animation; complex, manifold and systematic. Like language. Shaun knew the bush’s native tongue and could decipher it as easily as spoken English. Walking through bracken that grew taller than he, that ancient dialect came to him, steadily and uninterrupted.

Silent? Not to Shaun. If city folk acknowledged sound at all, they often mentioned the birds. Yet they rarely registered the cuckoo’s gentle trill, the scornful chatter of thornbills, the thrush scratching in the leaf litter, or the rattle of a kookaburra’s beak. Nor did they notice the spiderweb that wasn’t there yesterday or the teethmarks in the bark of a wattle, let alone why they were there. But Shaun did; he knew it all. He was born to it.

He rode a pushbike on bush roads, half an hour to school. There he blended with those around him, happy to comply, responding readily to all the nominated programs. He often attracted the attention of others, yet he was no talker – perhaps it was the few words he chose that caused heads to turn and conversations to pause. From his classmates he drew little more than an uncertain stare, but Shaun’s teachers took particular interest, regarding him as something of a curiosity. Perhaps, they imagined, his progressive parents had instilled in the boy an unusual soberness, or perhaps it was his comparative isolation that caused him to respond with a degree of composure more common in older folk.

One sports day afternoon Shaun stood on the edge of the field watching some older boys playing cricket. Henley at the crease knocked the bat on the hard earth, brought his knees together and turned his elbow to the sky. There never was a ganglier child. All at once Shaun realised that his Phys Ed teacher was staring down at him, leaning in like a big old tree. The man fixed Shaun with his squinty eyes and suddenly declared, ‘You think too much, Bellamy.’ The boy looked up at his teacher’s planet-like skull against the pale sky, and tried to unpick that trenchant claim. Perhaps it was meant as advice, but instead, the comment simply gave Shaun cause for further reflection; how might he curtail the practice?

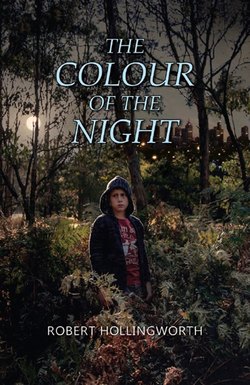

The thinking affliction had dogged him from the age of six. It was around then that another of his teachers casually asked the class what their favourite colour was. Most said blue or pink or green. But for whatever reason, Shaun spontaneously responded, The colour of the night.

‘That would be black,’ his teacher replied.

‘No,’ Shaun said, ‘it is only black because people are afraid of it. You have to look harder. Then it is a special colour that no one can copy, not even in the movies.’

It was the expression on the man’s face that stayed with Shaun, a lesson in itself. Had he crossed some forbidden line, pierced some inner sanctum reserved only for adults, for the qualified? He was not to know it but he’d merely baffled the man: what is the appropriate response to a child who takes extemporaneous questions so seriously?

You think too much was the latest advice, which only encouraged the boy to think quite a great deal more.

Apart from that one serious anomaly, Shaun attended to his maths, science and social studies like all the others. He had a laptop, and with the improved satellite signal, he carried a smartphone, utilising apps and predictive text just as they all did. But it was the natural world that drew him. When home-time beckoned, he entered the bush as other children entered an interactive game – although Shaun’s console control was little more than a snapped stick, his keyboard the whole forest, his mouse a mouse.

Ask Shaun what a peppermint is and he’d explain that it’s a rough-barked native eucalypt growing on the drier slopes with distinctive-smelling leaves that curve inwards to deliver raindrops closer to the trunk. Ask him how leaf-curling spiders curl leaves and he would describe the process in detail; ask him why dragonflies dart, why White-eared Honeyeaters sit on kangaroos, why the seeds of certain grasses have spiralling tails, and he would deliver an answer more comprehensive than most textbooks. Hardly anyone in the world knew why night-flying moths were attracted to the light. But Shaun did.

Much of his knowledge came from direct experience, but not everything. While other children read Harry Potter or The Hunger Games, Shaun absorbed his parents’ textbooks – history, biography and the natural sciences – with the assiduousness of a quiz-show celebrity. But Shaun’s prize lay in the sheer joy of knowing, in drawing a little closer to the birds, animals, wildflowers, grasses, insects, fungi and ferns. At twenty paces he could separate the dicots from the monocots – monocotyledons, to use the correct term.

Yet Shaun could not distinguish a Honda from a Hyundai, a terrace from a tenement, a bagel from a baguette; these were objects beyond his terrain. The big city was far to the south, a humdrum of men and machinery, women and fashion, urgency and speed. In Shaun’s mind it all flashed brightly: glinting cars reflected in shop windows, trucks and traffic, ambulances, diesel buses, networks of wires – and people: striding, bumping, texting, preoccupied.

With his mother, he’d once visited his Aunty Adele before she moved, before she was divorced. Her brick house seemed indistinguishable from many others, the front façade strapped back and forth by whizzing cars and bicycles; a kind of incessant monotony unseen in the green world. But it held a certain charm and, though now a distant memory, that blur of frenzy occupied a special place in Shaun’s eleven-year-old mind.

After his aunt’s divorce she moved into the city along with Elton – Shaun’s older cousin – but to which part the boy wasn’t sure. At night in his room, listening to the chuck-chuck of Marsh Frogs in a nearby pond, he conjured an image of that inner-city location and contemplated an excursion there as others might consider a trip to Moscow or Marrakesh. It was far away and exotic and some day he’d go, he was sure of it. Some day he’d navigate that foreign land; it would broaden his knowledge, allow an appreciation of things he knew only from films, books and the internet. Some day.

ELTON BRIGHT – Shaun’s older cousin – would rather contract the self-replicating Storm Worm virus on his PC than be subjected to a half hour in the bush. He’d rather lose his warrior status on Guild Wars 2 than venture to a place where trees replaced power poles, where grass supplanted the grey exactitude of concrete.

He didn’t need it. He had everything he could possibly want in his blacked-out bedroom: friends, information, games, videos, and the entire world to traverse, from the loftiest mountain, real or imagined, to the inner workings of another’s mind. Elton could tell you what a friend from Switzerland – that he’d never met – had for breakfast that morning, and what he’d dreamt about last night. It was all right there on the net; was there any reason to go outside?

On this day, as he sat in his darkened man-cave, awaiting responses on Twitter, he spontaneously and unconsciously unzipped his trousers and released his penis. Well, why not?

It was not at all uncommon for Elton Bright to be sitting at a screen conversing in one chat room or another, and not at all uncommon for his member to rise. Yet the two events – the conversing and the rising – were unconnected and an erection was no more irregular than a yawn or a cramp in the foot. Sometimes he’d shuck down his pants and stroke the thing like a family pet. And sometimes while he did it, he’d click on www.sweetly.com stored in his Favourites to observe some anonymous girl’s body, a young woman, purportedly a teenager, posing naked in a wheat field, astride a bicycle or sprawled in the sun next to a hotel swimming pool. But he rarely took interest in pornography – that other kind of imagery featuring the full gamut of sexual deviation – although he sometimes wondered who did. In Australia, it was a 1.5-billion-dollar industry with most viewing it for free, so how many Australians weren’t looking at it? For Elton, that question was more fascinating than the imagery itself. It wasn’t that he felt any sense of taboo; in fact it was the familiarity that rendered it dull, like looking at the back of one’s own hand – no surprise could be found there at all.

He’d first discovered digital nudity at the age of five. On his father’s computer, an innocuous Search word had brought forth a naked woman who seemed to be drawing nutrition from her own breast, prompting instinctual recollections within him. Another woman appeared to be crawling – something he’d done himself only a few years earlier – and a naked man was pressing his body against her buttocks, causing her breasts to oscillate magically, like a ball on a string. He grunted, she groaned, and none of it made any sense at all. At seven, with his own laptop, he’d chanced upon all manner of male and female body parts not unlike some of the peculiar fruit and vegetables he’d observed in his mother’s shopping trolley. It all seemed rather homely and commonplace. So, these days, when he sat stroking himself, he often continued in an online conversation – or sometimes he brought up a picture of some trim girl just to share that brief, casual event.

He preferred this to any thought of a real-life partner, knowing that, unlike three minutes of an MP4, actual encounters always incurred further complications. Even his mother’s profession – which he understood completely yet kept secret (not even she knew he knew) – involved transactions he was not prepared to accept. So a completely passive, naked girl on the screen who would leave the room at the click of a mouse worked fine. He’d catch the stuff in a Kleenex, crump it into a ball and while typing a message to a friend in Spain, toss it into the bin. The bin itself was occasionally emptied, particularly when his room took on the musty smell of a caged animal and threatened to disrupt his online concentration. It was his one concession to untidiness. In all other respects his body, his clothes and his bedroom were as neat and clean as an unoccupied hospital ward, and he had a large collection of selfie pics on his iPhone to prove it.

Elton was the quintessential Gen Y modern male.

But he did not see himself as such; he was just a normal person living in a time when technology had triumphed, when sanity had at last prevailed. He was overjoyed that society had permanently escaped the twentieth century, a bygone era when a totally different world existed. Back then, life was literal rather than conceptual, and people were impressed by things that today only excited the dull and naïve: garden blooms, sunsets, mammals in the sea, a kite in the sky, a ‘stolen’ kiss. Back then, even a wink was wonderful, while ecstasy could be found in a ripe apple.

What an absurd, disturbed, witless world it must have been. And how isolated. Elton could not imagine having a mere handful of friends. He had several thousand, in fact he was more popular than all his forefathers put together. And without difficulty he could stay in contact with each one of those several thousand friends, conversing regularly, confirming the stupidity of other people’s lives, sharing anecdotes and playing games. Some of his friends he had even killed for.

ELTON LIVED with his mother Adele at 42 Frederick Street, the centre terrace in a block of three. Her bedroom upstairs adjoined her son’s but was right at the front of the building. Her window faced the main thoroughfare, and from there she could look out across a sea of single-storey rooftops; a choppy vista of red tiles and tin running all the way to the horizon. In the distance, the irregular central-city monoliths stood clustered amid an amber monoxide glow.

When Adele had first moved to that inner city suburb, the urban image from high up seemed exciting and epitomised everything important about making a fresh start. But now she rarely bothered to glance out; familiarity had sucked the novelty right out of it and the view had become as predictable as the boys who kicked over the council bins on Thursday evenings.

Elton, whose bedroom was right behind hers, couldn’t care less about the view, now or ever. On the day they moved in, he pulled a single drape across his own small window and pinned it shut with a line of thumbtacks, denying the trifle of daylight that had previously limped through the smeary pane, any possibility of backlighting one of his monitors. He invested a little of his estranged father’s money on a long melamine benchtop which now ran the length of one wall with a return on each end. Atop it sat four monitors, two of them connected to the one hard drive, the others operated from laptops and all wirelessly connected to the internet. In front of this there were two ergonomic office chairs and it was from one or other of these that, all day and night, Elton met, talked and played games with his several thousand friends.

To suggest that Elton was agoraphobic would not sit well with the young man. Hadn’t he undertaken a science degree? Hadn’t he managed a whole year of it even while his parents were going through the last ludicrous stages of divorce? You must complete your studies, his father had commanded. If you want to make me proud, please finish the course. And so he did, one year at least, not to make his father proud but to obligate him: he had two years to go. Now, with the intermittent conscience money from his corporate father’s canny dealings, Elton could afford to defer before deciding on the actual trajectory of his life. But he’d already decided that a professional career was objectionable – one in the family was enough. And surrounded as he was by his devoted circle of worldwide friends, it just didn’t seem necessary to go anywhere.

Except to shop. Clothes were Elton’s only real interest in the tangible world. For apparel, he would go anywhere, traverse the length and breadth of the planet – New York, Hong Kong, Barcelona, Beijing – and he saved to Favourites a list of online stores. Stuff arrived in the mail, usually a softpack of socks or shirts or a sports jacket which he donned with some solicitude before skyping a confidant in another corner of the globe.

Elton was no slouch, no nerd; he would not be an overweight, bespectacled, pimply Übergeek, and he had a Wii EA Sports Active 2 Cooperative Multiplayer Fitness Game stationed to one side of his workbench with its own dedicated flatscreen monitor. His mother had bought it for him as a Christmas gift. She hunted it down, added it to the shopping cart and proceeded to the checkout. There she clicked Buy, entered her PayPal details and within three days the box turned up at their front door. She wrapped it in coloured paper and placed it one Christmas night beside the pointy plastic tree.

‘If you are to stay inside then I want you to exercise, Elton,’ she’d insisted. And so he did, every day in the first week; she even joined in – twice. But keeping the boy to the rigid program turned out to be more exhausting for her than for him, and in the end the twenty-minute circuits to target upper and lower body as well as cardio, deteriorated to a simple verbal exchange:

‘Are you exercising?’

‘Yes.’

‘Don’t forget.’

‘No.’

Adele wanted to be fit herself; it was one of the first things she thought of as Randall drove away in the family car, his vintage number-plate, ICU, disappearing ironically into the distance. Good riddance.

Now without a partner, it seemed logical to take special pains with her appearance. She had no intention of attracting yet another untrustworthy male, but with only the walls to appraise her, it was easy to let appearances slip. Her new career also dictated that she should stay fit, though she refused to take over Elton’s neglected trainer. Instead, she pumped her limbs briskly around the block each day, regarding her trim figure in the bathroom mirror as reward alone.

But her son Elton never walked anywhere. He never advanced beyond the outer walls of their new dwelling – except to fetch the rubbish bins, which obliged him to venture at least as far as the rear yard. He hated it all, the green and brown and blue above, the uneven earth, the air weighted with dust, diseases and allergy-bearing pollens. Inevitably a breeze would bat him back inside to the comfort of a space that was square and clean and neatly defined. He could hardly imagine how he’d once caught the tram to uni and back, a concept that now seemed so pointless, so alien.

Adele did not object. Her son had other qualities, for instance his application to tidiness. How could any mother be critical? He managed his bedroom with unmatched diligence; he was clean and shaved and his creaseless clothes were parked on hangers or meticulously pressed and placed in drawers. His shoes were tiered on wire racks according to a hierarchy of regular use. To Elton, it all made sense: his orderliness in the regular world meant he could immerse himself in cyberspace free of encumbrances.

ADELE BEGGED her leave at 11 p.m. The parliamentary function that she’d been asked to attend had not gone well. Her client turned out to be a bore, leering unpleasantly and finding opportunities – where none actually existed – for sexual innuendo if not downright crudity. But as Adele understood, every profession had its disappointing moments, even hers; its unexpected ruptures just when things should be going smoothly. She was good at her job and she knew it, but no degree of skill could compensate for certain ineptitudes, for acts of stupidity. As soon as her agreement had been fulfilled, she excused herself and caught a cab home, closing the front door quietly behind her.

Upstairs, she was not at all surprised to walk past Elton’s door and find him still up and illuminated by the blue light of several screens. Normally he’d have his door closed but he was not expecting her home so early. She went to her room, stepped out of her evening dress and pulled on a tracksuit. In the mirror, she removed her lipstick, brushed out her L’Oreal leather-black hair and tied it loosely at the back. She returned to Elton’s bedroom and leaned against the door jamb.

‘Hi.’

‘Hi.’

‘Want to take a break?’

Elton didn’t turn. ‘Can I catch you in a minute? I just have to finish something.’

Adele never argued, well aware that her son had crucial things to complete. And so it was. Sargeras, the fallen Titan, had unleashed an army of unspeakable evil on the Draenei. They’d been slaughtered in the thousands and tonight Elton had joined his guild to repel the Burning Legion in its demonic quest to undo all of creation. A fierce battle had ensued and many despicable monsters of the Horde had fallen to his blessed blade. There were rivers of blood yet his guild was not yet safe. His guild: 128 others from all regions of the world.

Adele went downstairs and switched on the kettle. As the whistle blew, she heard Elton thumping down the carpeted stairs. The clock read ten past one.

‘Jesus, I’m buggered.’ Elton stretched his slack-muscled frame and marched towards the fridge. A photo of the two of them, taken right there in the kitchen, was held to the heavy door with a giveaway magnet. Elton gawked into the fridge and closed the door again. He thought about asking his mother why she was home so early, but decided against it. That was her business, a subject he habitually avoided.

‘Had a call from Morry this afternoon,’ Adele said and put a cup in front of him.

‘Who?’

‘Morris – your Uncle Morris and Aunty Sharon.’

Moz and Shaz. It was they who’d suggested the friendlier appellatives, so why did his mother insist on the antiquated Uncle and Aunty? They’d chosen a country lifestyle, whatever that was supposed to mean. Elton hadn’t spoken to them for a couple of years and these days they rarely came in from the bush. A disappointment really; they used to bring such good presents.

Adele sat on a stool opposite her son and placed a wet teaspoon on the cutting board.

‘I had a talk to young Shaun as well.’

A vision flashed through Elton’s mind: a small tanned two-legged creature in shorts and nothing else running through the scrub with a projectile of some kind.

‘The wild kid?’

‘He’s not a wild kid; he’s your country cousin. He’s just turned eleven and he wants to come and visit.’

Elton thumbed some digits on his iPhone and Adele watched him. ‘He sounds like a very bright little boy,’ she said. ‘Lots of questions, very curious about everything. He said he wants to visit the State Library. He asked if he could come down during the school holidays. To see what city life is like,’ she added, studying her son. ‘I was thinking, maybe at the end of the month.’

‘Okay with me. As long as he can take care of himself. Has he ever caught a tram or a train?’

‘Probably not, but you could show him.’

‘Is that necessary? Let’s talk about it, Mum.’

But of course they didn’t, at least not right then. They put their cups in the sink and both retired once more to their rooms. Elton had to return to World of Warcraft; the mission was not yet complete. In this realm he was known to others as the Dark Knight, a class of man who would stop at nothing to eliminate the diabolical evil, who would gladly sacrifice his compatriots to destroy the enemy. His empty soul knew nothing but vengeance.

Later, Elton visited other worlds, other quests. But his life wasn’t all games: he was also very much attuned to political and social concerns. A Facebook link to some atrocity in Iran or Iraq always prompted him to press the Like button. And many of those he followed on Twitter offered anything up to 140 characters on important social shifts. Every night was a long night for Elton, but that was his usual routine; he worked by night and slept a fair portion of the day, just as his mother did.

IT WAS A BRIGHT sunny day, though Elton didn’t know it. He was sitting in the dark watching a live feed from Toronto. Australian singer Jordie Lane was playing at The Planet and Elton streamed it onto one of his monitors. On another PC, he saw that Lane was asking for requests on Facebook. Elton wasn’t especially interested in the singer’s brand of down-home music but he did like the idea of a national profile. So he typed a request on Lane’s Facebook page and moments later the singer announced in real time that Elton Bright of Melbourne would like to hear ‘The Publican’s Daughter’. Elton smiled and switched off the live feed.

Just then the front doorbell rang and Elton’s body went as rigid as a shop mannequin. He listened for his mother.

‘Elton, can you get it?’

Reluctantly, he lumbered down the stairs just as the doorbell rang a second time. Through the spyhole he saw a young man about his own age, standing casually, thumbs in pockets. Elton stayed perfectly still, and it wasn’t until the bell sounded again that he removed the safety chain and opened the door. On second inspection, he decided that the guy was a little older, perhaps even into his twenties.

‘Hi. I was wondering if you want your old bike.’

Elton eyed his visitor suspiciously. ‘I don’t have an old bike.’

‘Whose is it then? The one up the side of the shed. I live next door and saw it when I trimmed the hedge. It’s a mess, rusty and everything … I thought you might want to part with it.’

Elton tried to think. Perhaps there was a bike; he recalled some angular object being unloaded with their other junk from the old house. The removalists must have shoved it up the side. It was probably his father’s.

‘What do you want with some random bike? Like, why don’t you get one off eBay? Be in better nick than ours.’

The older boy shrugged. ‘I just thought, if you don’t want it I could clean it up, pump the tyres and –’

‘Twenty bucks.’

‘Twenty bucks?’

‘Ten then.’

A motorbike blattered past and James paused.

‘Okay, ten bucks. Can … can I take it now?’

Elton hesitated before backing away from the door. He called to his mother. ‘We got a neighbour. Wants to buy our old bike.’

Adele came out of the kitchen drying her hands and introduced herself.

‘James Warner,’ the boy volunteered. He glanced at Elton, who was avoiding eye contact. The two were not at all alike. Elton was tall, thin and pale with red hair chopped by his own mother and waxed into soft spikes, while James looked solid and well-muscled. He stood with legs spread and his black hair, long and unwashed, fell about casually, a parody of his general demeanour. Adele broke the silence.

‘James, this is Elton, I suppose he didn’t introduce himself.’

Elton nodded and James addressed Adele. ‘He said he’d sell me his bike.’

‘Sell it?’ she laughed. ‘You should just take it.’

Elton shrugged. ‘He said he’d give me twenty bucks.’

‘Twenty? You said ten.’

‘Whatever.’

Adele suggested they go sort it out and Elton led the way into the backyard, his shoulders slumped as though the sky weighed heavily. James entered the narrow space between the wall and the fence and dragged out the bicycle. He went down on his knees and spun a pedal. Elton watched with accomplished vapidity.

‘Needs a bit of work,’ James declared, jolting Elton back to consciousness. ‘The tyres might be buggered. The seat’s wrecked.’

‘Don’t take it then; I don’t give a flying fuck.’

James pushed the bike towards the door. He could use it, he said, though he didn’t have the money with him. Elton told him to shove it through the letterbox later. He held the front door to let his neighbour out, and it surprised him to see the older boy lift the frame and carry it under one arm. He closed the door as soon as James stepped onto the footpath.

AN HOUR LATER Elton was assaulted a second time: the doorbell rang again. His mother had already left for work so the young man, once more, had no other option but to answer it himself.

‘Hi, I brought your money,’ James said, fishing into his pockets. ‘And I was wondering if you ever had a stack-hat to go with it?’ It was raining lightly and Elton could scarcely believe that his neighbour was standing there, apparently unaware of it.

‘A helmet,’ James added.

Elton thought he could visualise one stuffed in some tight corner, another thrifty preserve of his mother’s.

‘Ten bucks?’

‘That’s what I paid for the whole bike.’

‘Take it or leave it.’

James nodded, the beads of light rain sitting on his shoulders. ‘Do you want me to come back?’

The possibility of another visit stirred Elton to action. ‘I’ll go have a look, okay?’ He was about to shut the door but thought the better of it. ‘You might as well come in,’ he said, ‘out of the storm.’

‘It’s not a storm,’ James said and stepped inside. ‘Bit o’ bloody rain never hurt anyone.’

James stood nervously, in the middle of his neighbour’s living room, while Elton went upstairs. James hated interiors, even his own; what was it that bugged him? His mother had always known of it and blamed herself. As an infant, James screamed when left alone, as though a pin had been carelessly misplaced with his snap-crotch jumpsuit. How come no one at the antenatal class said anything about the constant bawling? Websites suggested she should switch off his light and shut the door, and they explained that if she refused to give in to the child, he’d soon settle down. But James never did and, in his teens, he began to abhor confined spaces as a cat hates a backyard kennel. Both his parents discussed the issue but his father Simon just shrugged. He was raised in an artistic house in Warrandyte where no one dared move without thinking laterally; as far as he was concerned, the boy could act as he pleased.

Except when it came to careers. Simon had hoped his son would follow in his footsteps. But James bypassed university for a job in roadworks, a move that smashed all records for lateral thinking. Both his parents were professional artists and a cultured life was critical, impossible without education. But James’s path was a different one, wide and concrete with expansion joints every three metres. He wanted to hone other skills: the manoeuvring of forklifts, bobcats and trucks; the operation of hydraulic jackhammers, cherry-pickers and vibratory rollers; expertise involving winches, welders and asphalt mixers. These were things his parents, with all their artistic training, could barely conceive, let alone understand. And each night James returned to his parents’ terrace at number 44. But he could easily sidestep any confrontation; he lived in a bungalow out the back, paid rent and kept to himself.

He scanned the shelves of his neighbour’s living room: carvings, handcrafts, figurines and other touristy nick-nacks. A large antique map of the world caught his eye and he ambled over to it. Half of Australia’s coastline was missing, allowing the Pacific Ocean to flood the interior. He thought of his own little abode next door. He liked his bungalow but even there he was hardly relaxed. Each night he’d warm some ordinary thing on the gas stove, eat it by the light of his fourteen-inch TV and then go out again. He’d walk the streets, anywhere, everywhere, with no sense of purpose at all, encouraged by the general feeling that he was at last free, of what, he couldn’t say.

But now, he needed a bike. One night he’d stumbled across three graf boys working on the defacement of a new apartment block. Over several evenings, James secretly watched them, noting the rapid application of their sweeping, deftly applied strokes, and he’d felt a peculiar stirring which he likened to the ‘inspiration’ his father had often explained. Art can be anything, the man had stated with some authority. You don’t choose your medium; it chooses you.

So James chose graffiti. Before long he was seeking out any surface on which to practise his newfound craft. On the front façade of his parents’ terrace the word framed in looping script could still be faintly detected. It was James’s tag: he had spray-painted it there and it was he who’d been paid by his unsuspecting parents to spray-paint it out again. But his own ’hood was limited; it could not compare to the wild frontier of other suburbs. For that, a bicycle was required.

At least ten minutes had passed since Elton disappeared upstairs to fetch the helmet. James listened for some sound but detected nothing. He edged across to the bottom of the stairs.

‘Elton?’ A bus pulled up out front; he heard the hiss of airbrakes and the engine burst to life as the driver pulled away. ‘Elton?’ he called again, and put his foot on the carpeted stairs.

On the top landing, he turned towards the front of the house and a room that was filled with sunlight. Stepping cautiously along the short passage, he came to a darkened doorway on the left, and across the lightless expanse, he saw the back of Elton’s head silhouetted against a computer screen, large headphones straddling his skull.

‘Elton?’

The chair swivelled instantly. ‘Jason! Sorry man! I had this message from some random guy in Connecticut and … There’s no helmet, or if there was one I can’t see it.’ James did not doubt it; his eyes were still adjusting to the gloom.

‘Okay, no problem.’ On the periphery of his vision he noted various aspects of Elton’s room, weakly illumined by the pixelated light. A single bed was pushed against the wall and the rest was all technology. No books, trophies, posters, memorabilia; not even scattered clothing, which was the omnipresent feature of his own room. James wasted no time exiting that dim, dark hole and out in the passage he breathed deeply, allowing his pupils to contract before descending the stairs.

‘I can let myself out,’ he said, and headed towards the door. ‘By the way, it’s James, Elton.’

‘What?’

‘My name. It’s James, not Jason.’ As he stepped into the street, he called again. ‘See you,’ he said, though that future prospect was furthest from his mind.

JAMES’ PARENTS, Simon and Stefanie, always arrived home in the same car. Their art studios were almost a suburb apart but it was a regular routine for Stef to swing by and pick up her husband on the way home, and the procedure was reversed each morning on the trip out. Rarely did either venture into the other’s work area. They liked their own privacy, their own ‘autonomous space’, but there were other reasons as well. Simon was a conceptual artist. He abhorred the idea of ‘art as product’, of ‘object making’, of ‘project’, of ‘frameability’. His work was ephemeral, installation-based, interactive, site-specific. By contrast, Stef was a painter and no further explanation was required. She came home enveloped in a faint aura of pure gum turps, with oil paint in her pores and a smudge of sienna up the cheek. What she envisaged as the ultimate work, striven for but never quite attained, was so far off Simon’s radar as to seem like a lost language once spoken by primitives.

Clearly, it was not Stefanie’s philosophical stance that originally attracted him to her. Instead, as Simon would happily attest, it was her superbly proportioned figure, her wicked laugh and the twinkle in her brown eyes. He was Head of the Art Department and Stef was his student. As art school seemed to dictate, the young woman cared little for virtuousness, so flirtation with a senior lecturer that lapsed into sudden liaisons in the storeroom was not at all out of the question. A relationship flowered and it was not long before it occurred to Simon that if he was ever to keep her, he should propose.

They both declared their love – though it was desire that underscored their union. Stef craved recognition but, as all art students know, there is a yawning chasm akin to the moon’s Sea of Tranquillity between being an artist and being an important artist. For Stef, Simon was the bridge and she crossed it, up the embellished passageway of the Government Registry Office. For Simon, Stef was the perfect companion and at the best gallery events he felt flattered to be with her: the sparkling young graduate who was more effusive than most, who brazenly confronted even the most conceited senior art figures.

But that was then, the early nineties, and time had intervened. Now they were husband and wife, like so many others, sharing expenses and household concerns, a night at the cinema with a meal afterwards and, every so often, a holiday overseas. They generally agreed on most things and could sidestep their differences, such as their diametrically opposed artistic sensibilities. At least most of the time.

Stef glanced at her husband, twelve years her senior, and marched towards the kitchen. ‘Are you ready for your show?’

‘When is anyone really ready?’ Simon called from the sitting room. ‘I’ll get done what I can and work it all out in situ.’

Stef carried a bottle of sav blanc to the lounge where Simon had already slumped into one of the black leather couches. She poured two glasses.

‘Are you going to use the bag piece?’

‘The bag piece …’

‘Yes, you know, those plastic bags you collected with the beach sand and –’

‘This new work isn’t about environment, Stef. Did you read the catalogue essay?’

‘Of course. But it’s hard to see exactly what you have in mind for the … you know … what you intend to –’

‘Not even I know that. Not precisely. I want osmosis and transmutation to play a role.’

Longstanding experience had taught Stef that it was time to switch subjects. She took a sip of wine and leaned back in her own armchair. The radio was whispering in the corner and Stef heard mention of a squabble for leadership. It reminded her of the special service they’d attended at the National Gallery for the passing of a leading Labor man.

‘We should invite that couple we met at Clive Cunningham’s funeral.’

‘It was a Memorial Service, Stef.’

‘You know what I mean. Those collectors, what was their name?’

Simon discharged one of his trademark huffs. ‘Those two haven’t been buying for years; they just live off their reputation. I can’t stand people like that, swanning in and swanning out, expecting the art world to court them.’ He looked away. ‘But I think it was appalling that our own National Gallery director didn’t show.’

‘At the service?’

‘Yes. He should have been there.’

‘He was there, I saw him.’

‘Really? Damn it, why didn’t you mention it?’

Just then Jess came through the front door, their daughter. As she reached the foot of the stairs, her mother called after her.

‘Jess.’

‘Yes Mum.’

‘Hi.’

‘Oh, hi Mum.’

‘How was your day?’

‘Good.’

‘Did you go to the interview?’

‘Yep.’

‘Any luck?’

‘Won’t know for a while.’ She put her hand on the banister.

‘What do you intend to do now?’

The girl turned to face them. Jess was typical and atypical; she did not look like many eighteen-year-olds yet she looked exactly like some. Self-created tartan bondage pants, platform boots, remnant top over a grey T-shirt, a clutter of silver rings and requisite piercings, spiked hair both black and fuchsia-red, black kohl surrounding fiery green eyes, face as pale as parchment. She was not quite goth, not quite emo.

‘You mean right now, this minute, or some other time?’

‘Tomorrow. Are you going to apply for something else, or do you intend to wait on the job at the electrical store?’

Jess thought for a minute, avoiding her parents’ eyes.

‘I’ll let you know, okay?’ She turned and stomped up the stairs.

Her mother watched her retreat. The girl was younger than James by two years and when she was born, Stef had already decided on a different approach to her upbringing. James was squeezed out less than a year after she and Simon married – and was completely unplanned, completely unprepared-for. During that pregnancy she’d cursed ten times a day – putting the tally somewhere near three thousand – spat bile regularly into the bathroom sink and kicked the vanity which vibrated the full-length mirror causing her reflection to shake its head disapprovingly. It was one thing to flout the rules and ignore social correctness, another to disregard the incredible stamina of sperm. But she lived through it and before long she was pregnant again. Stef was now equipped with considerable experience and expected to raise the newborn differently. But her plan had anticipated a particular type of person, a version of herself. Jess, unfortunately, seemed like the product of another woman’s genes.

If James was a crier, Jess was an outright anarchist, even as a four-year-old. Was it a clash of personalities? Couldn’t she expect her darling daughter to respond decently, logically, sensibly? But the tiny child had screamed and kicked and rejected every approach. What were she and Simon failing to notice; what were they missing; what did the child want? She had toys, books, musical instruments; they took pains to explain complex issues, introduced her to the best art, food, restaurants, people – and still the child rebelled.

Even now as she sat sipping wine with her husband, Stef knew that they’d failed in some way. They’d both long recognised that being highly trained artists did not equip them for parenting. Yet couldn’t they expect a little encouragement? Like the children they were attempting to raise, they needed nurturing too, just a little confirmation, a sign that their actions were a tiny bit appreciated. But they received no such incentive and found it very easy to capitulate.

Stef recalled her daughter going through puberty and shuddered. It was then that the girl adopted a real penchant for deviation. Beyond logic or reason, she’d entered a behavioural realm that required two years of mental-health professionalism to finally dispel. Stef was reminded of the sleepless nights monitoring her daughter, and the day the kitchen knives came out of hiding and were again returned to the drawer. Was that period finally behind the girl?

‘Anyway, I’ve never liked that man.’ Simon appeared to be addressing the bookshelves.

‘What?’

‘He always acts so superior, when it’s the curators who do all the work. A figurehead, that’s all he is; someone to address the media.’ He looked at his wife. ‘I’m talking about the Director.’

Stef wondered where her wine had gone, and poured another, her eyes drifting again to the empty staircase.

SHAUN CRAWLED under the Fringe Myrtle. Sure enough there they were: a small cluster of Gnat Orchids, their flowers not much bigger than gnats. With his stomach embracing the warm earth, he counted them: about twenty, and each was turned in the one direction; towards the best light, the boy assumed. Why were they there? He’d not seen Gnat Orchids in the forest before. But he was used to nature’s peculiar way of throwing up something unexpected, as though all things were possible if one only waited. That was the interesting thing about life: watch patiently, remain observant and the nuances revealed themselves.

‘Shaun! Wood! Wood!’ It sounded like the cry of a native pigeon echoing through the forest – wood wood wood – but his mother’s high-pitched calling reminded him of a different mission. He sat up to see her in the distance, standing on the deck, leaning out like the figurehead on the front of a sailing ship. ‘Okay!’ he yelled. He took hold of the wheelbarrow and pushed it down the track. Further into the bush, his father had taken the chainsaw to a fallen wattle and the logs were still scattered in the grass. Twenty Gnat Orchids; who would have thought it?

STEF AND SIMON wanted their daughter to remain living with them, even if they were obliged to support her forever. At least that’s what they told others. But whispering across a yellowing pillow in the dead of night, they sometimes wished to Christ she’d snap out of her morbid self-pity and take some responsibility for her life. Maybe a stint on the dole in a rented flat would shake some maturity into the girl, make her part with the tongue stud, labret and clitoris ring – the last, an act she’d defiantly announced to her mother one Christmas Eve. What was going on in her head? If only she would put some meaning in her life.

Meaning; it was everything to Stef and Simon. Above all else, life and art – not necessarily in that order – had to be meaningful: One’s actions should always add new substance to the world. It was the least they could expect of their daughter, raised as she was in such a rich cultural environment. But Jess had a response to this which was difficult to deflect: What does meaning mean?

Jess went upstairs to her room and closed the door. She sat on the bed a full minute before turning her attention to the tattoo on her forearm. Was it fading? Was it turning green? She was sure it was darker and clearer a year ago – what’s the point if it’s going to fade? A fleur-de-lis, its crossbar had been artfully placed along the raw rib of a scar, still red and raised, giving the tattoo a slight 3D look. It was very special; that little ridge of raised tissue, the first experiment, followed later by the full production. And how alive that had made her feel! For a short and precious period, a unique kind of knowing, unavailable in the outer world, eclipsed everything and left the emptiness far behind. She lightly touched the image on her arm and lifted her gaze to the cracked mirror sitting on the dresser. She could barely see her own eyes, hidden as they were in the surrounding kohl and overshadowed by her shock of wildly disarranged hair.

She was not to know it, but Elton’s room next door was exactly opposite hers and at that moment, if the party wall could be magically removed, he’d be staring precisely at her.

She sat for a few more minutes before going into the passage and along to the old nursery at the back. That room had a wide window looking down onto her brother’s bungalow. She saw lights on in James’s kitchen. It was a good time to catch him, between his working day and his wandering night. She slipped quietly down the stairs, glancing at her parents, whose backs were now turned, their eyes fixed intently on the latest TV news atrocity. Sirens wailed, at least twelve dead, she heard the newsreader say.

She went out the back way across the small concrete yard and tapped on her brother’s door. James was in the bedroom and had seen her coming.

‘What?’

‘Can I come in?’ She didn’t wait for an answer. ‘What’s up?’

‘Nothing. Why do you always ask that?’

‘Got anything to eat?’

‘Have a squiz if you like. I don’t know.’ Jess didn’t bother. She sidled through and sat on his bed. James was kneeling on the floor with his back to her, his new bike upturned on sheets of newspaper. He was spraying it black.

‘Shouldn’t you do that outside?’

‘Too damp – you need dry conditions. Don’t you like the fumes? Thought you’d be into it.’

The idea did appeal and she felt her heart skip. ‘I need some stuff, Jimmy. Do you think you could get something for me?’

‘Jessica.’

‘Just a bit o’ speed or something, mate … Don’t freak out. If you can’t, you can’t. Just thought I’d ask that’s all, no biggy.’

‘I told you, Ryan doesn’t like bringing it to work. And I don’t like it either. Means one of us has to carry it around all day. Anyway, I can’t afford it anymore.’ He looked sharply at her. ‘You’re costing me a fortune, Jess. Wean yourself off it or get your own money.’

Jess picked up a pair of his underpants and held them to her nose. James snatched them away.

‘Fuck off, you freak! What do you think you’re doing?’

Jess laughed.

‘Can I come with you tonight?’

‘No.’

‘Where will you go?’

‘Wherever.’ He rattled the can of spray. ‘Is your computer working?’

‘Nah, still fucked. Must’ve downloaded some fucker’s viral shit. Don’t want to touch it, ’case it climbs up my arm.’

‘I might know someone who can fix it,’ her brother suggested. ‘The guy next door. He sold me this bike. He’s a tech head, got an amazing stash of gear. Do you want me to ask him if he can have a look at it? I bet he’ll do it – for a price though; the prick knows the value of things.’

‘I don’t want no stranger in my room. He might be some mutant geek that, you know –’

‘He’s not like that. ’Bout your age, straight as a freakin’ flagpole, lives in the total dark – you might like him.’ He flashed her a grin.

‘Can you take it over to his place?’

‘No way! I hate his cooped-up idea of a life, him and his mum squirrelled away, sleeping through the day.’

‘What’s his mum do?’

‘Christ knows. Nurse, I reckon – or a prosty.’

‘You lookin’ to root her?’ She bounced lightly on his bed.

‘Bloody hell Jess, was that necessary?’

She reached out with her foot and pushed him in the back.

‘Piss off, woman!’

‘Get the geek to fix the computer, okay? Take it over to his place. As long as he doesn’t want the world for it.’

James spat a little more spray onto the shiny black frame. ‘Don’t worry, I’m keeping a record of every cent you owe me.’

Jess left and James righted the bike, studying it carefully. He could see himself flashing down side streets, no lights, silent and unseen as a blacksnake, keeping to the shadows. A helmet was hardly necessary and was only needed for his signature style. Like the Green Lantern’s logo, he’d paint it up symbolically, though the artistry would hardly approach his parents’ ideals.

Just then there came a tap on his other door – the one that led into the back laneway. Behind all three terraces there ran a cobblestone alley along which, a century earlier, the nightman had travelled, emptying battered drums of human waste into a horsedrawn tank. But now that artery was hardly utilised, except as James’s usual access.

The knock came again and James called through the door.

‘Hello?’

‘Hello! It’s Nikos from the corner. Got a minute?’

James opened the door to find a thickset middle-aged man standing in the fading light.

‘Nikos,’ he repeated, ‘but people call me Nick. That’s my property on the corner, number 40, where the verandah is.’

James knew it well, the third of the three terraces, the one right on the corner of Frederick and Ward. It had an awning out over the footpath straddling both streets and beneath it, the original full-length shop windows were still in place.

‘You like the verandah? I built that. Used to be one there in the old days – I got me ’ands on an old photo, out of a newspaper. Someone knocked the original one down, so I put it back up again – and painted it two-tone. That’s what they used to do back then – paint the verandahs two-tone.’

James wasn’t sure how to reply.

‘Anyway, I didn’t wanna trouble ya,’ the man said, ‘but don’t you work for the council?’

James nodded.

‘Thought so. Seen ya doin’ that new footpath on Johnson Street – that’s my café over the road. Know that one? Best spanakopita in this fair city and that’s a fact. Proper Greek tucker.’ He looked into James’s eyes. ‘Tell you what I want; I need the services of a man who knows how to use an excavator and I thought, if I hire one, an excavator that is, maybe you could drive it for me? Make it worth your while o’ course. How much do ya think it’d be? For cash?’

‘Sorry mate, I don’t want any afterhours work, okay?’

The man stood in the laneway, hands on hips, and lightly angled his head. James could see his brain ticking.

‘I’d make it worth your while.’

‘No.’

‘Cash in hand.’

‘Sorry, mate.’

He didn’t want to leave. ‘Tell you what: I got the original plans to this building. Want to see ’em? Pretty amazin’. There used to be a cellar in my place, right on the corner. It used to be a butcher shop and I bet they stored all their meat under the floor. In the cellar. Pulled up the floorboards expecting to see a bloody great hole but it’s all been filled in. I’m going to dig it out again. What d’yer reckon?’

How, James asked, did he expect to get an excavator into the room? Through the side window, Nikos declared, unperturbed. Not the whole thing of course, just the bucket. He admitted it would require real skill and again implored his neighbour. Cash in hand, he repeated.

‘I wouldn’t try it if I were you,’ James warned him. ‘Too risky. Anyway, I can’t help you. Sorry.’ He stepped back and put his hand on the doorknob.

‘Right. Okay. If you change your mind you know where I am, eh?’

NIKOS CHRISTAKOS expected to score handsomely from the purchase of number 40. It had been passed in at auction and he’d made his successful offer a month later. From that moment on he told anyone whose attention he could arrest, just how rapidly his investment was multiplying, adding small increments weekly. In Nikos’s opinion it was already worth fifty percent more than he’d paid, and with the ongoing renovations – for more than a year now – its value was rising like the morning sun.

He didn’t live there himself. Instead he rented it to two tenants who had a bedroom each upstairs and a shared bathroom and kitchen on the ground floor. He’d had no trouble finding renters. He’d placed a small ad in the suburban newspaper and a dozen people turned up. Most recoiled immediately, one woman actually reprimanding him, declaring that he had no right to offer such shabby conditions to potential tenants with the advertised claim: Excellent shared accommodation – suit professional couple. But two people put some cash on the line, there and then, no contracts, no agents, no anything.

One was an Afghan, the other an Englishman. They’d eyed each other curiously on that first day as they handed a month’s rent to their new landlord. The older Englishman was tall and blond, with a narrow face and pale complexion. Pronounced pockmarks climbed up his neck and scrambled onto his cheeks. The Afghan was short and dark, his hair, beard and eyebrows as rich as black velour. He was perhaps ten years younger than his fellow renter and wore a blue, long-sleeved shirt and grey trousers. The Englishman was similarly dressed – blue shirt, grey trousers – which was something they both noticed. But their cultural differences far outweighed any coincidental dress code. Regardless, as each nodded in agreement to the landlord’s lack of terms, they tacitly accepted one another, though as neither could produce a single reference, the decision was hardly theirs to make.

WHEN ARMAN Khan took off his shoes and stepped into his new sleeping room, six metres by five, it felt as though a significant milestone had been reached. His room and his window that looked down onto the side street and onto the bright yellow roof of the taxicab he now drove. He scanned the interior and smiled at the immensity of the double bed with the sturdy steel legs and decorative headboard. He did not require it, an extravagance of space he would not normally consider, but it came with the room. So too did the freestanding wardrobe and a wooden dresser, not antique but very old and of a style not seen in Afghanistan. The dresser had a mirror affixed and Arman gazed at his reflection within its bevelled edges. He’d had his hair cut since arrival, believing it aligned somewhat with his new country, but he’d kept his full beard in accordance with the Prophet’s example. He noted in the poor light that only the whites of his eyes were apparent between eyebrows and beard. He exposed his teeth; white and straight, though a back molar sometimes throbbed. His own mirror and his own dresser.

He spent the weekend cleaning everything, starting on the right with his left hand according to Sharia law. He began with the dust high up on the picture rail and finished with a cleansing of the varnished floorboards, washing and drying them carefully with a square of towelling. From a factory outlet near Sydney Road, he bought new sheets, a pillow and bedcovers, and he had a brand-new mattress delivered.

It was upon this that he lay back on the third night and ruminated on his extremely good fortune. There had been so much tragedy that his current situation shone among past events like a jewel in the mud. He lay blissfully and gazed up at the pale blue ceiling. Such an odd sensation: alone and content in his own sleeping quarters, a single man, thirty-five and a refugee. He hated that word: ref-ugee, and the implications of it. He winced at the thought of the three years he’d patiently endured in Kabul until he could be processed. And in his mind he saw again the landscape of the motherland growing smaller through the aeroplane window, his passage made possible with the proceeds of his father’s estate: a burnt-out mud-brick dwelling on the outskirts of Paghman.

In Melbourne, he moved in with three relatives – all men – who had already settled in Yarraville. For a while it worked, but things were never quite right and Arman recollected the miserable mat they’d given him in the laundry. Without work, he’d been obliged to cook and clean for the entire male-only household. He’d undertaken the women’s work conscientiously and not without pride, but much to his chagrin, the others confirmed that his manner and physicality were perfectly suited to it. He’d felt unequal, ignored and disrespected. All that kept him going was the possibility of finding his own abode; that and becoming a cab driver, wearing a neat uniform and working alone behind the wheel of a car in an official capacity.

Lying now on his own mattress, he ruminated on the nights spent by a bedside lamp studying the Melway, memorising all the main arteries and prominent suburbs, and the tram rides he’d made to mark it all off in his mind. He rose from the bed and looked down from the window onto the roof of the company cab shining brilliantly in the generous Australian sun. At last he had escaped the critical eye of others, including those of his own family. Now he could concentrate on work, prayer and self-improvement, and life should be much easier.

BENTON HATTERSLEY’S bedroom was further to the rear on the same floor and now he was also arranging his things but with somewhat less diligence. A room was a room as far as he was concerned; he’d lived in more than he cared to remember. He put his socks and underwear loosely into the same drawer and sat down on the edge of his single bed. Where to position his computer? He frowned, the permanent furrow between his eyebrows, an index of that regular habit.

Like Arman, he had mixed feelings regarding his past, and he too had surrendered his homeland for fear of retribution. But even now, after ten years away, he still missed his home town of Hertford, north of London, and he missed also, the life that he did not shed but rather, had taken from him.

If people could see him now they might never guess he’d come from such noble stock. His ancestors had been prominent citizens, five generations of Hattersleys, the family crest stamped prominently on letterheads and the upkeep of their sixteenth-century Tudor manor house provided for by investments in shipping and tea plantations located in far corners of the Commonwealth. But all had gone horribly awry when the mounting debts began outweighing the income. Stocks were sold, then the companies and finally the family property itself. Benton was still haunted by the expressions on the faces of those locals, the way they had shaken their heads in disbelief, that such an empire in the space of a few years could be reduced to an invalid male and his aging sister – Benton’s mother. He was seven then and still to learn that his birth had been the outcome of a fleeting romance, the first of a string of monolithic embarrassments for the family that had only ended with the sale of their ancestral land.

For seven years he’d been kept behind closed doors in that family manor house. Now in his forties, he would readily admit that he’d been an introverted child. What strange and strict times. His grandfather, who could not accept the gradual demise of the dynasty, had required of little Benton that he learn piano, read Proust, Gide and Bertolt Brecht, and undertake French and Latin. None of it raised a single hair on the boy’s downy skin, an epidermis that had barely seen daylight, let alone the sun. What strange and strict times indeed.

In his new domicile, Benton untangled the leads to his computer and, despite himself, could not help but reflect upon those lamentable, formative years. All he’d ever wanted was the company of other children, yet when he moved into the small Hertford cottage with his mother, nothing improved. Unnaturally protective, his mother discouraged outside friendships, but she needn’t have worried; for his own part Benton had no idea how to acquire such things. From that time forward he’d watched others play, laugh, push and punch, and he’d done all those things as well – but always alone in the confines of a small loft bedroom. Now, in mid-life, he recollected the countless hours he’d stood at the smeary casement window. Even in his teens he’d continued to stand at those same old multi-panes, staring out, watching others share their company but never with him.

He was fourteen when Olga Bergeson had come briefly into the house as a renting Year Nine student from Sweden. He did not interact with her, but when she finally left he’d discovered a pair of her underpants beneath the bed. He snatched them up, took them to his room and examined them as a lepidopterist might study a rare butterfly. He held them to the light, inhaled them and, later, wrapped them around the hardening shaft of his fourteen-year-old penis. But it was all harmless play, teen curiosity: he liked the girl, and as he’d happily attest, he’d done nothing wrong at all.

What followed, however, he’d always keep secret – after all, he had a private life just like everyone else. He would never tell of his first big collecting phase. He would not recount how his normal day had been summarily converted to a quest, namely, the frenzied acquisition of underwear from other people’s clotheslines. Large bloomers had disgusted him, but small panties – even boys’ Y-fronts – had monopolised his imagination completely and he gathered enough to cover his entire eiderdown twice over. Laid out in rows, it was hard to decide which were the best, which to prize most highly – perhaps the boys’ blue jocks, tiny and tight, with a motorbike embroidered on the front. But he was very young then and, these days, he’d rather forget that teenage hobby. And forget also the period in his twenties when his activities went full circle, back to the wearers themselves, the ones he still watched from the old casement window. All he ever desired was intimacy; something that he felt sure should exist, somewhere.

He was a dozen years their senior when at last he felt equipped to approach the children, when he finally found the courage, wit and social skills necessary for interaction. The kids loved it; how he entertained them and how enthralled they were with the grown-up things he could teach them. But why had it caused such unnecessary grief? All would have been fine if the boys and girls could keep secrets. But they let him down appallingly and it was the wrath of parents that eventually put him on an offenders’ list.

Now, in these rented premises on Frederick Street, the latest in a string of lodgings, he still wondered how things could have turned out so badly. Life had such unexpected twists – and not the least was his mother’s death while they were still sharing the Hertford house. He was thirty then and her passing devastated him – but not as much as the news that she’d left everything to her invalid brother. Benton inherited a damaged Guarnerius violin once owned by his grandfather, some oval miniatures painted by a lesser-known portraitist and a leather-bound set of the works of Hemingway. That was when he moved to Cambridge, rented a neat little cottage in a quiet street and left the previous thirty years behind.

Sitting in his new North Brunswick bedroom, he again frowned. During that time in England when things were going so well, how was it that one autumnal day he’d found himself back in court? It wasn’t his fault. It was the boy across the street who’d approached him; it was he who asked to earn some pocket money and he who wanted to watch some silly program on TV. No one had forced the child to do anything. And who says a thirty-year-old can’t have young friends? Where was the harm? Of course that kind of friendship entailed certain physical liberties, intimate bridges to cross, but the boy would merely gain some mature life-experience – and under the guidance of someone who knew.

For that one casual event he was put on the national register, which meant there was nothing left to do but leave. And so he did, for the new colonies, a country young and fresh and so far away that it was like being born again. It was warm and prophetically pleasant, that day he stepped onto the tarmac at Tullamarine and marched towards the terminal. At last he could lose himself, wander on the plains of anonymity. But, as he soon learned, this was also the real heart of loneliness – which prompted his introduction to one other kind of travel: the transporting effects of alcohol.

He’d experienced a step down in his professional career. Having previously specialised in the design of renewable energy equipment for the car industry, in Australia, he found himself employed at Unitex installing home entertainment systems. At week’s end most of the staff descended on the Rickard Hotel, just three doors down from the office, and this was where Benton was introduced to the luscious liquor, as Milton put it, and where he first discovered a special kind of faux-confidence.

It had come to him one evening that no one wanted prolonged, thoughtful conversation; it was the smart and springy comments which endeared, the one-liners that could be tossed off like a text message or the half dozen words of Twitter. He could easily manage that and he learned to slip his two bob’s worth into the hotel’s witty repartee, recognising that his chronic lack of social ease went largely unnoticed. It was all quite funny, really.

And in time, Benton learned to invoke some of his aristocratic legacy. Calling upon the monologues of his forebears, he discovered that he could hold forth in front of anyone with all manner of preposterous statements – and people seemed to accept it. He remembered the first ludicrous thing he’d said to his Afghan flatmate the day they’d met: You understand, young fellow, this is a temporary measure. My inheritance will soon be forthcoming and when it does, I intend purchasing something much more agreeable, a property by the river perhaps, but certainly a long way from this unremarkable little borough. Arman’s attention had been magically arrested. You understand I’m not used to such ordinary arrangements. But in the meantime I suppose we should just make the most of it, eh?

DESPITE BENTON’S apparent lack of regard for their living quarters – or perhaps because of it – Arman warmed to him. Call me Ben, the man offered genially, unless you intend a formal dissertation. He represented so much of what Arman was not: urbane, eccentric and unwilling to accept the mediocrity that life often dished out. Benton was a gentleman and Arman assumed that his way of speaking came naturally; it was the English language at its purest. It intrigued him and challenged his own grammar and, altogether, Benton appeared to be just the sort of person with whom he might share a dwelling – though he did not tell his housemate that ben meant ‘co-wife’ in Pashto.

But for all of that, the Englishman’s manners were a mystery: eating with both hands, passing items with his left, clearing the nose with the cloth in his right. And of course his fellow renter was an infidel – he had not yet found God. But Arman was learning tolerance in all things and there was no one he felt more inclined to tolerate than the blond, gangly, forty-something Englishman with the cultivated accent so refreshingly unlike his own.

With their bedrooms upstairs just a passageway apart, it was imperative that they learn to live harmoniously. Yet coming as they did from extreme cultural polarities, some kind of common ground was necessary – which turned out to be the kitchen downstairs. The room was by no means attractive and Arman declared it a cooking hole, to which the other man replied, ‘But the roses, my good fellow, what lovely roses!’ and directed Arman’s attention to the pattern on a well-worn teatowel that hung over a plastic-coated rail. Upon first arriving, both men had assessed with some gratitude, the included kitchen fittings: a fridge near the door, an old gas stove pushed into a brick recess, a wooden table and three chrome chairs standing on flecked vinyl flooring.

Additionally, there was a large, laminated sideboard backed against the opposing wall. It was atop this that Benton, in the first week of renting, installed a large flatscreen monitor and wired it to a closed-circuit camera that overlooked the main street. Nikos, their landlord, approved; it might add value to the property. He called in from time to time, to collect the rent and discuss the excavation that was soon to take place in the front room facing Frederick Street. Nick believed it had once been a butcher shop, but for the present, that room was completely unusable, its windows papered over and its floor no more than compacted earth. The middle-aged man from Mykonos explained to his tenants that he’d enthusiastically torn up the Baltic boards expecting to find the cellar but found it had been completely filled in with earth. Yet, if an ancient subterranean chamber had once existed, he declared, then he would dig the damn thing out again.

It was the unusable front room that had prompted Benton’s surveillance camera – there was no other way that he could observe people in the outside world. But now he could look on just as he’d always done: privately, discreetly and without alarming his subjects. From the comfort of a kitchen chair he could observe everyone endlessly and he knew it was only a matter of time before he would see something of genuine interest, something he desired yet dared not hope for.

SHAUN WALKED his bicycle home. A sharp stone had ruptured a tyre, precipitating an hour-long journey along the unmade road instead of a twenty-minute one. But it took the boy much longer. Every short while, something beyond the road’s shoulder would catch his eye and he felt obliged to investigate. First it was a case-moth cocoon suspended from a barbwire fence and the species needed to be identified. Next, he came across the faint tracks of a large monitor lizard, sometimes called a goanna. He followed those delicate markings from the dusty road into the dense bush, but it was all to no avail. The creature might be very close by but Shaun knew that monitors liked to cling to the far sides of tree-trunks and that as he moved, the lizard would also move, maintaining its position furthest from him.

Shaun sauntered on. With so much time on his hands it was an excellent opportunity to think, to exercise the affliction that had dogged him most of the past decade. He formed in his mind a detailed image of his Aunty Adele’s new home, the two-storey Victorian-style building with the large door that opened right onto the footpath. There was a bus stop next door, and a power pole that leaned slightly, holding aloft a thick black cable that was attached to the building’s stucco rendering. There were two windows on the second floor where he could identify scalloped and tasselled blinds raised slightly and a plaited cord hanging down. The wooden window frames, which were painted a slightly darker tone, were in need of a bit of work, and high above it all, four traditional finials, domed and decorative, stood starkly against the skyline.

How useful Google Earth could be! If Shaun could not yet visit, at least he could travel there in virtuality, courtesy of NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography. That technology had placed him right outside the front door and Shaun had scooted up and down the street, climbed all over the building, danced across the rooftop, checked all the nearby stores and cafés, and studied most of the geographical features. There was a park nearby and a small creek – and a bicycle-repair shop next to a recently converted power station. And standing outside his aunt’s front door he could determine the exact condition of its paintwork. All he could not do was ring the bell.

Could not ring the bell – what a marvellous prescription for living, a reminder that life is to be experienced as much as viewed. Humans were good at seeing, Shaun knew, better than other mammals that required movement to notice things. But seeing, for humans, was also tangled up with knowing: Oh I see, people would say, and so they did, but that was no reason not to experience things in equal measure. Get the balance right, his father had instructed.

The light was fading when he reached his own drive and pushed the bicycle down through the old Manna Gums. His father was already at home and Shaun took the bike to him. They removed the tyre together, working quickly before the treeline obscured the sun; that same flaming ball that, no doubt, was simultaneously mantling in peach-coloured light, the front of his aunty’s residence.

WHILE BENTON held vigil at the monitor, Arman cooked – even trialling such rare and foreign delights as beef sausages, potato mash, peas and pastry with tomato sauce. And when everything was cleared away, Arman would join his fellow renter in front of the closed-circuit screen. They both liked sitting there; and over a cup of tea, the main beverage of both their countries, they took turns commenting on the particularities of all who passed or stopped to await the bus.

It became obvious to Arman that their proclivities coincided. He could never understand the degree to which women, in particular, were prepared to expose their flesh and he recognised that Benton felt similarly. Both of them were more inclined to note the size of a man’s nose than the appearance of a woman’s bare legs. Shouldn’t they remain covered? Either way, women did not interest Arman at all, even though he had tried so hard in Kabul to be dutiful. As the Quran expressed it: After fear of Allah, a believer gains nothing better for himself than a good wife …

Was there any other way? He knew of his exiled cousin who had fallen under the spell of another man. Such an abomination cast anyone so-touched into the bowels of hell to burn for all eternity. Arman would never contemplate such an idea; he would not fall prey to the evils of Sodom and Gomorrah. Better to enter into an arranged marriage, though in this new country, thank Allah, that imperative was no longer imminent.

In the little kitchen, by the light of a single incandescent globe, Arman felt he’d discovered in Ben an enduring common interest, seated as they were, side by side observing the waiting commuters, or in their absence the passing foot-traffic. Arman was learning Western ways, Ben was awaiting something else, and from time to time even their landlord joined them. Nikos, also a bachelor, quickly fell into the spirit of things.

‘There’s them Asians again!’ he declared. ‘Never used to be any around here. My opinion: the Chinese are looking to take over our country. Know what I mean?’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Arman, with some confusion, attempting to juggle the apparent hierarchy of nationalities.

Benton nodded and smiled. He liked the idea that the other two were entertained by his unusual innovation. With a flourish towards the screen he would regularly repeat, ‘What do you say, chaps, can we imagine a more thorough embodiment of reality TV?’

Friends at close quarters. It was a new concept for Benton and it required practice. There were still times when the proximity of others elicited a strange and disconcerting nausea. On these occasions he was obliged to retreat upstairs, and it was here behind closed doors that he took out his special Irish tumbler and a four-sided bottle that shone liquid amber even in the bad bedroom light. He did not much appreciate the taste, but that wasn’t the point. With glass in hand, he would turn on his computer, log on to his regular internet site – the one with the children – and there at last he would feel truly inspired.