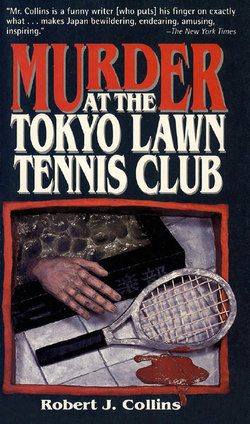

Читать книгу Murder at the Tokyo Lawn & Tennis Club - Robert J. Collins - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Shig Manabe was one of the nicest guys in the world. You would have to search far and wide to find anybody with a bad thing to say about the man. Some people, for no earthly reason, are like that.

All this is not to say that Shig had been living the life of a recluse. He had been involved in some of the more momentous events of his day and age.

Born in Yokohama, Shig moved with his family to Seattle as a ten-year-old. His father was employed by a Japanese trading company, and Shig quickly adapted to the American way of life. As a grade-school and junior high student in the relatively somnolent years before World War II, he fancied baggy trousers, wore brown-and-white saddle shoes, and cheered for the old Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast Baseball League.

The Manabe family beat a hasty retreat back to Japan in early 1942, but the sayonara party for Shig at his school was not without a few tears from his teenage classmates. He was even awarded his varsity letter in baseball weeks before the annual sports banquet.

Finishing high school in Japan had not been easy. English was completely banned, and Shig's Japanese language skills were rusty at best. But he kept his head down, went through all the correct motions, and avoided having the daylights beat out of him by those sensitive to the subtleties and nuances of "foreign pollution."

Shig graduated from high school in 1944 and was immediately drafted into the Imperial Army. Not being particularly keen to shoot people, Shig volunteered for an elite corps of personnel deployed as translators and interrogators. (Careful not to reveal too much under the circumstances, Shig demonstrated his English skills with the sentence: "Shoot the Babe Ruth bastards from the sky down and kill.") He got the assignment and sat patiently as he underwent intensive language training from men who had learned English from a book.

The tour of duty in China was not without its difficulties. The most trying aspect was interrogating a group of prisoners that included his old physical education instructor from Seattle. Shig shared his ration of rice, soup, and bamboo shoots with the man. (As history was later to record, Shig was eventually given the key to the city by the mayor of Seattle.)

Shig became a prisoner of war in September 1945 and was returned to Japan in time to experience one of the most severe winters in Tokyo history. After various interviews with the Occupation forces, Shig was released from prison and hired to translate documents and official pronouncements. At the time he weighed 45 kilograms—down from his high school weight of 70 kilograms.

People seemed to like Shig, and eventually trusted him. His scholarship to the University of Michigan was the direct result of friendships developed during the Occupation. He received his bachelor's degree and married a classmate—the daughter of a pearl importer from New York—on the same day. Shig wore a yarmulke at the wedding, along with his formal kimono. The newly-weds settled in Manhattan's Upper West Side.

Shig got involved. Down through the years he was an active member of the American Heart Association and served on the board of the New York Home for Foundling Children for ten years. He even raised money for the Republican Party in New York State.

The pearl business had been good to Shig and now, at sixty-eight and semiretired, he divided his time between Tokyo and New York. When in Tokyo, his favorite haunt was the Tokyo Lawn Tennis Club. If anything, he probably had more friends there than anywhere.

The tennis game that day had not been altogether satisfying. Shig and his regular partner, known collectively as the Silver Foxes, had built up a 5-3 lead in the first set, but they blew it and lost 5-7. The Silver Foxes really came apart in the second set and lost 1-6. A basic fact of life is that the strategy and skills of veterans are often obliterated by the speed and strength of youth.

A hot Japanese bath after a day of exercise is one of life's great sensual pleasures. The temperature in the ojuro was just right. Shig's head leaned against the rim of the tub—his body stretched out—with his toes emerging from the water at the other end. Those toes had been through a lot—shuffling back and forth to school in wooden sandals, running around bases in ill-fitting baseball shoes, tromping in rotting dampness through jungles, standing in cardboard on icy pavement, and chasing diabolical drop shots in tennis. The second toe on the right foot was a particular problem, having been shattered by a bullet through the boot during the surrender ceremonies in China.

Locker room sounds—the banging of doors and the rumblings of athletes excusing performance—filled the air. The pervasive smell of liniment was everywhere.

Unfortunately, none of these thoughts and sensations registered with Shig Manabe. One of the all-time good guys, about whom nary an evil word was spoken, was up to his eyebrows in the bath—now turning pink and beginning to bubble crimson. The American Heart Association, the New York Home for Foundling Children, even the Republican Party in New York State were on their own. No locks in Seattle would ever again be opened by Shig's keys.

On the floor next to the bath was Shig's tennis racket, a dynamically balanced graphite model with impedance tension and a shock-absorbing grip (designed to reduce the incidence of tennis elbow). The rim of the racket, it was later determined, bore traces of decidedly nontennis activity—blood, matted hair, and microscopic chunks of brain matter from the skull of the one of the nicest guys in the world.