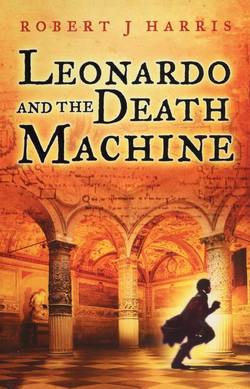

Читать книгу Leonardo and the Death Machine - Robert J. Harris - Страница 10

5 A BIRD IN FLIGHT

ОглавлениеWhen Leonardo came out of the workshop the next day, he walked straight into an ambush. He had scarcely gone a dozen yards down the Via dell’Agnolo when he was seized and hauled into the dingy alley beside the coppersmith’s shop.

Before he could cry out, a grimy palm clamped itself over his mouth. His arms were pinned to his sides from behind and a glint of metal appeared under his left eye.

It was a chisel that had been honed to a razor-sharp edge.

“If you know what’s good for you, you’ll keep quiet,” hissed a voice.

Leonardo recognised the speaker: Silvestro’s apprentice, Pimple-face, breathing fish fumes and garlic into his face. Twitcher must be behind him, holding his arms.

Pimple-face slipped his hand from Leonardo’s mouth but kept the chisel close enough to slice his cheek open if he tried to call for help. With his free hand he felt inside the leather satchel strapped to Leonardo’s belt.

“What’s he got there?” Twitcher asked.

“The usual stuff – brushes, palette knife, paint rags,” Pimple-face replied. He looked Leonardo over. “Not dressed so handsome today, are you, Leonardo da Vinci?”

“Somebody steal your fancy gear?” taunted Twitcher.

Leonardo was wearing the drab working clothes he had come to Florence in while his one good outfit was being washed and repaired after yesterday’s misadventure. Determined to protect his dignity, he responded stiffly, “I only dress up for special occasions.”

“Like visiting old Silvestro, you mean?” sneered the Twitcher.

“That’s what we come about,” said Pimple-face. “When you was visiting, you didn’t see nothing, right?”

Leonardo squirmed. “I don’t know what you mean. I only came to deliver a message.”

“Oh yes, the bill,” chortled Twitcher. “Old Silvestro was fit to throttle his own grandma when he opened it.”

“And he was even madder when we told him we saw you nosing around,” said Pimple-face. “He sent word to his client.”

“Now this client, he don’t like nosy people,” said Twitcher. “He told Silvestro to take care of it.”

Pimple-face leered unpleasantly. “So here we are.” He grabbed the front of Leonardo’s tunic and pressed the chisel against his cheek.

Leonardo swallowed hard. His copy of Silvestro’s diagram was tucked inside the tunic, perilously close to Pimple-face’s clutching fist. He had spent half the night finishing the drawing, borrowing one of Gabriello’s candles so he’d have enough light to work by.

“An artist’s work is his own private business,” said Pimple-face. “Understand?”

Leonardo couldn’t nod without cutting his face. “I understand,” he breathed.

“What did you see?”

Leonardo could feel his heart pounding against the folded drawing. “Nothing,” he replied meekly.

Pimple-face released his grip and patted Leonardo on the head like a clever dog. “That’s right, you didn’t see nothing, you don’t know nothing, and you don’t remember nothing.”

With the edge of the chisel still so close to his face, Leonardo wished for a moment that were true.

At a gesture from Pimple-face, Twitcher released him. Sniggering, the two apprentices scuttled off into the crowd that was passing along the Via dell’Agnolo.

Leonardo slumped against the wall and felt his cheek to make sure the skin wasn’t broken. Things were getting more dangerous than he had anticipated. Was it worth risking his life just to gain favour with the Medici? No, only a fool would get caught in the middle of this power struggle.

He pressed a hand to where the drawing was hidden. Maybe he should burn it before Silvestro and his friends discovered he had made a copy of their design. But no, he could not help feeling that this was the key to his future, his chance to enter a wider world.

The clang of a nearby church bell made Leonardo start. He would have to sort this out later. He was already late. He darted out of the alley and ran the rest of the way to the market.

Sandro was at the agreed meeting place: beside the statue of Abundance in the centre of Florence’s Old Market.

“Where have you been?” he exclaimed when he spotted Leonardo emerging from the crowd. “I’ve been waiting for ages.”

Raising his voice above the hubbub of barter, Leonardo said, “I couldn’t leave until I finished all the chores Maestro Andrea had for me.” He had decided to say nothing about his encounter with Silvestro’s apprentices until he was certain of what to do.

They were surrounded by butchers’ stalls and the air was buzzing with insects drawn to the raw meat. Sandro swatted away a fly with his uninjured hand. “Well, it hasn’t done my stomach any good, I can tell you. Every time I think of this plan of yours, it hurts like there was a sea urchin rolling around inside it.”

He set off, awkwardly manoeuvring his way around a pair of squabbling vendors. Leonardo wove through the crowd, keeping in step with his friend.

“There is one thing we need to settle first,” Leonardo said, drawing level. “My fee.”

Sandro stopped by a fish stall where trout, pike and eels lay on the slab. The eyes of the fish were wide and their mouths agape, as if they were still surprised at being netted.

Sandro gave Leonardo an equally startled look. “Your fee?”

“Why are you so shocked? Don’t tell me you’re doing this portrait for free.”

“That’s different. I’m an artist and you’re only an apprentice.”

“Apprentice or not, this is professional work I’m doing,” Leonardo said in his most reasonable voice. “Maestro Andrea says that money is the lifeblood of art.”

“Friends should not discuss such matters,” said Sandro, walking on. “Money is the poison that blights the flower of affection.”

“What’s that supposed to be – a proverb?”

Sandro shrugged. “It’s what my brothers always say when I try to borrow money from them.”

They were passing a trader whose caged birds were stacked one on top of the other like bricks in a wall. At the top of the stack was a lark that was beating its wings feverishly against the bars of its cage. Being so close to the sky seemed to make its confinement even more unbearable.

Leonardo knew how it felt. “I’ll tell you what,” he suggested, “why don’t you give me a gift of some sort?”

“I suppose that would be acceptable,” Sandro conceded, “as long as it’s a very small gift.”

“All right – that bird,” Leonardo said, pointing.

Sandro tilted his head and gave the bird a dubious look. “It doesn’t look very clean.”

“Look, just buy me the bird and we’ll call that my fee.”

“Six soldi,” said the birdseller, holding out his hand.

“That’s outrageous!” objected Sandro.

“Do you want to spend the rest of the day arguing,” demanded Leonardo, “or do you want to get to the Torre Donati while there is still light to paint by?”

Sandro sighed and reached into his money pouch. Carefully, he counted the coins into the birdseller’s hand. “I hope you appreciate that you have made me destitute.”

“Don’t worry,” said Leonardo, lifting down the cage. “Soon you will be famous and wealthy enough to buy a thousand birds.”

He inspected the latch on the cage. It was a simple loop of wire and he easily worked it loose. The cage swung open and the bird hopped out on to his outstretched palm.

“What are you doing?” asked Sandro, aghast. “It’s going to—”

The lark took flight. Whipping the folded paper out of his tunic, Leonardo used the back of it to make some rapid sketches of the bird as it soared off. It left the market behind, arcing gracefully across the sky to disappear behind the dome of the Duomo, Florence’s cathedral.

“That’s my money flying away!” Sandro exclaimed.

Leonardo surveyed his work. “What’s the point in having a bird if you can’t watch it fly?”

Sandro peered over his friend’s shoulder. In mere moments Leonardo had made several lightning sketches of the bird in flight, showing in sequence the movements of its wings and tail as it soared over the rooftops.

“How could you see all that?” Sandro asked. “It was too quick.”

“Not if you pay attention,” said Leonardo. He tapped himself on the temple with his stick of charcoal. “Everything I see is stored up here like a stack of pictures one on top of the other.”

“Well, you don’t need to go to all that trouble just to paint a bird,” said Sandro.

“It’s not about painting,” Leonardo explained. “I want to understand how it flies.”

“It flies because that’s what it’s meant to do,” said Sandro. “A bird is meant to fly in the air, a fish is meant to swim in the sea, a man is meant to walk on the ground.”

“And an apprentice is meant to keep to his place,” Leonardo added under his breath. “Well, we’ll see about that.”

They soon arrived at the Torre Donati, a lofty fortress of yellow stone. Sandro gripped the brass knocker, which was in the shape of a dragon’s head, and rapped three times on the door. It was opened by a plump, fastidious man in a crimson tunic who waved them brusquely inside.

“Tomasso, the chamberlain,” Sandro whispered to Leonardo. “This is my assistant, Leonardo da Vinci,” he informed the chamberlain. “Is your mistress ready for the sitting?”

Tomasso took a backward step and called out, “Fresina!”

A girl of about thirteen came scampering from a room at the back of the house. She had a slender face and long yellow hair tied in plaits. She also wore the distinctive grey robe of a slave.

“Fresina, go to your mistress,” Tomasso instructed. “Tell her the painter is here.”

He emphasised the word ‘painter’ as though he were announcing that the weekly delivery of garden manure had arrived.

The girl bobbed her head and scurried off.

“I believe you know the way,” Tomasso said to Sandro.

“You’d think he was the master of the house,” said Leonardo, as Sandro led the way up a flight of steps.

“We artists are an insignificant group compared to the bankers, merchants and clothmakers who run the city,” said Sandro. “Our job is simply to serve the needs of the rich, the same way a cook or a tailor does.”

They entered a spacious room on the topmost floor where the sun slanted through the westward facing window. The chamber itself was panelled in polished oak. On one wall hung a tapestry depicting the Labours of Hercules while under the window stood a large chest decorated with pictures of a deer hunt.

Near the centre of the room stood an easel on which there was a small picture about one foot square. Leonardo walked over and examined it. The chestnut hair, coiled in the latest fashion, was almost finished, as were the delicate ears. The eyebrows had been sketched in, and there were the faintest lines of a nose, but the rest of the face was blank.

“It’s quite good, as far as it’s done,” Leonardo said.

“Whatever you do, don’t spoil it,” said Sandro anxiously. “Make sure you follow my style. Never forget that the way to please your subjects is to bring them to perfection in the portrait. Imagine they have been carried up to Heaven and paint them as they would appear there.”

“I don’t know what people look like in Heaven,” said Leonardo. “I can only paint what I see.”

Sandro began unpacking his art supplies and setting them out on the table to the left of the easel. “You will have to mix the paints on the palette,” he said. “My wrist is plaguing me like a wound today.”

“Leave it to me,” said Leonardo.

He set to work preparing the various hues and colours he would need to complete the portrait. Sandro pestered him throughout the whole process, giving him unwanted advice about the use of white lead and viridian green.

Leonardo lifted up the palette. “If you don’t stop fussing like a fretful mother, I’ll crack this over your skull,” he warned.

It was at that moment that Lucrezia Donati walked into the room.