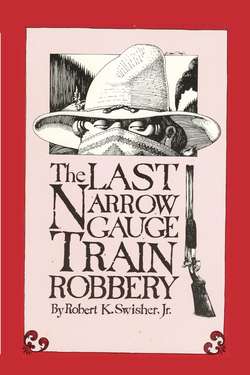

Читать книгу The Last Narrow Gauge Train Robbery - Robert K. Swisher Jr. - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

If one were to fly north from Chama, New Mexico, one would start at 7,000 feet and fly over the mountains looming up to 14,000. It is a green, lush land in the summer, dotted by fir and spruce and aspen stands. The high peaks and meadows pasture for sheep and cattle in the summer. In the winter it is white with snow. The land around the foothills of the mountains is divided, for the most part, into private ranches; big spreads boasting of times in the past when they made a living. Now ghosts of what they were, most are owned by oil men and sheiks who use them for tax write-offs and hunting. They run a few cows to help them feel like cowboys. The ranches are worked by young men, men with large drooping western hats, boots with their Levis tucked in the top, and spurs that ring when they walk. Dead men already, hanging onto a dream that died before them. They are but tokens on the ranches, living legends who, for a few years, will live their glory; sleeping with the young cowboy girls poured into their tight Levis, dreaming of six guns and cattle rustlers, reading their Louis L’Amour books until the day comes when they get one of the little cowgirls pregnant and move into a trailer, then rising each day to work in the mill or drive a truck.

The mountains that are excluded from the boundaries of the ranches are considered wilderness or natural forests. A huge tract of land running between Pagosa Springs and Durango on the west, and Chama and Antonito on the south and east remains relatively unspoiled. Left to the government, it will be spoiled. The trail heads are areas where one may start into the wilderness either on foot or horseback. Motorized vehicles are not allowed. In the lakes that dot the wilderness, brook and cut-throat trout leap into the air from the stillness of mirror-smooth water. The people who come to this country come to be alone or to be with friends. It is a small haven for the lost and disenchanted ones who come to be with the wind and the forest. It is a place to run to, to breathe the fresh air, and to see one’s life.

Before the 1860s, there was nothing back in the wilderness except a few outlaws and a few Indians. By the 1870s, gold and silver had been discovered, and a rough-cut road circled up and through Grouse Mountain, Cumbres Pass, and Munga Pass, ending at the small mining community of Platoro. Here, miners worked for the large mining company until they had a grub stake, and could then head into the mountains to pan the streams and dig the outcroppings in search of their glory hole. The trails that came from these miners are the trails that people follow now, searching for quiet. It is a timeless place, a place where the seasons come and go without our help. A place where nature is alone most of the year, sealed by remoteness from our perils.

Snaking around the edge of this wilderness is the Narrow Gauge Railroad. Running partially by the super highway, it is a black, smoke-belching attraction that makes all the cars stop and look in wonder at a portion of our past. The train runs by the highway for ten miles before it cuts off into the forest, climbing over the passes to coast into Colorado. It is a living memory, a memory of gold and silver, guards with double-barreled shotguns riding with the cars, nervous, waiting for the sound of the rifle or crack of a pistol. Hanging in the office of the Narrow Gauge Railroad is an old, browned-out photograph of four men who tried to rob the Chama train. They are strung from a cottonwood tree by the river, their necks extended out past life, dreams of riches and no work gone forever. Standing around the four is a group of smiling men, their hats pulled over their eyes, their guns crossed in their arms. There is no date, there are no names. It was just another event in the mountains not worth remembering.

When the mine played out, and the rivers did not yield enough gold to warrant any more exploring, Platoro, Chama and the railroad died, slipped peacefully back into the seasons. A few crooks and ranchers stayed on, along with a few hermits. Not until the 1960s did the land wake up once again. Hippies, the disenchanted ones, moved in from all over the world, looking for peace and love and the truth. They found Mexicans who hated Anglos, cowboys who hated Mexicans and about everything else, including cold, and the truth. But they also found the wilderness. A wilderness not overrun like Yellowstone or Yosemite. And then, as if by magic, people began to remember the forest. People all over the country were filled with the fear it was ending. One day there would be only photographs. Elk and deer would be stuffed or in zoos, and people began to flock to the outback. It was here that Bill, Ronnie, Riley and Frank came every year, came to remember old times and old places, came to laugh at the days when they cut wood to heat their homes, and walked through the snow to the outhouse. They laughed about being stuck in the woods, carrying guns to scare off the Mexicans and cowboys who didn’t like longhair s.

It is different now. People don’t care about the hair. There are enough problems without worrying about someone’s hair. Like the train, the gold, silver, and the big ranches, Frank, Riley, Bill, and Ronnie settled onto the shelf of antiquity. They settled their shoulders a little, and took life for what it was.

“It’s a mind-fuck,” Ronnie exclaimed.

“It’s a cocksucker,” Frank declared.

“It’s a bunch of shit,” Bill knew.

“It’s a photograph of a rose-colored asshole,” Riley observed.