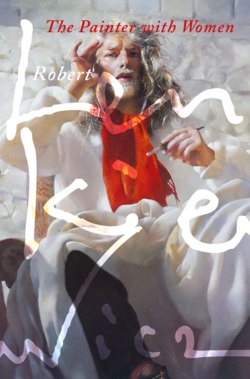

Читать книгу The Painter with Women - Robert Lenkiewicz - Страница 8

THE DOPPELGANGER 1988–1989

ОглавлениеOn 1 April 1988, five years after he had embarked upon his seventeenth Project, Robert Lenkiewicz’s large-scale exhibition Observations on Local Education, totalling 150 paintings with over 500 sitters, finally opened in his own studio premises on Plymouth’s Barbican. By his own admission, he had found the Education Project a challenging and depressing experience, which had been reflected in many of the paintings. Aside from notable exceptions such as the virtuoso The Glue Sniffer (sometimes called Syd Sniffing Glue) and the ambitious The Deposition, the mechanical, mundane and repetitious nature of the system he was recording resulted in a substantial number of portraits which were, in Lenkiewicz’s own words, ‘literal and uninspired’. Unusually for Lenkiewicz, these were painted onto white canvas rather than his usual black, reinforcing their close tonal values – grey paintings of the grey people who were in control of the education of this country’s young.

The exhibition had been open for less than a month before Lenkiewicz was questioning the purpose of the whole Project. The opening night had been packed with friends, patrons, family and his usual circle of supporters, but since then it had met with an apathetic response. The number of people visiting the exhibition was already dwindling. The two large volumes of notes, printed at great expense, which chronicled the views of his sitters on the education system, were still piled high, attracting little interest.Neither had the heavily-researched sociological aspect of this Project, or indeed his two previous ones on Sexual Behaviour and Death, done anything to redeem his critical standing in postmodern art circles.

Less than three weeks after its opening, in his diary of 20 April, Lenkiewicz observed:

Education Project very quiet. Little local interest – and of that 90% dull and plain stupid. Must consider the sense of these Projects. So much work – so little interest – and a great deal of vacuous, dilettantish carping. After seventeen massive studies on human behaviour, I should be used to it. Feel a strong leaning towards reclusive hard work for the future only.

A couple of days later, on opening the studio, Lenkiewicz found his problems mounting when he was greeted by the ‘usual Thatcherite bills.’ With no doubt his recent first-hand experience of the cultural state of the nation still in mind, he added, ‘what a crippling abomination that woman and her ruthless philistine crew are.’

The final straw appeared to come with an article in The Times, covering the arts scene in the city to mark the four hundredth anniversary of the Spanish Armada. Lenkiewicz was classified with Beryl Cook, whose retrospective was then being staged at Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, as ‘two rather eccentric characters’, without any reference at all to his Education exhibition. In the following day’s diary (28 April), Lenkiewicz commented:

Tiresome trivialising of my work in the context of Bernard Samuels’ [Director of Plymouth Arts Centre] witterings about Plymouth’s ‘two eccentric artists’ – Beryl Cook and myself. Such a dim-witted article. Would much rather have not been mentioned than be in such silly company. No mention of Education Project – usual drivel. I get used to it. Seventeen of them now; all strangely invisible. They can never be re-staged – seems so odd that such intense activity and enquiry attracts carping trivia and nothing else.

This was immediately reinforced by Plymouth City Museum’s refusal ‘under all circumstances’ to display the Education Project poster, despite thirty seven of their staff sitting for one of the largest paintings in the exhibition. Lenkiewicz seemed to be growing resigned to it:

They are too busy with their Beryl Cooks and [Spanish] Armada bullshit to notice real labour and inquiry. After seventeen Projects I now feel almost completely invisible – and indeed it is quite pleasant really.

During the following weeks Lenkiewicz turned his interest to redesigning and reorganising his ever-expanding library with little time spent painting in the studio. At the request of a Devonport tenants’ association, he took some time out to create a large mural which featured the local residents with their MP Dr David Owen, ironically titled The Ascension into Heaven. Started on 16 May, it was officially unveiled at the beginning of August and completed shortly afterwards.

Ria as Janus. 1988. Oil on canvas, 60 × 138 cm

The original painting of Ria measured 190 × 138 cm before Lenkiewicz later cut down the canvas.

Determined to rethink his future in the light of recent experience, Lenkiewicz’s next intended Project on ‘The Family’ had been put on hold, although a few paintings from this period bear an inscription of ‘Project – Family’ on the reverse. Eventually, it was in early summer in his personal life where a new, intense passion finally began to refuel his creative energies, stimulating a return to the more private enquiries into the nature of the ‘love relationship’, which had been the prime focus of earlier Projects.

In his diary entry of 6 June, he had sensed ‘something begins’. By 23 June, he had ‘treated and sized three large canvasses black’. Before the end of the month, the first paintings in a new, as yet unspecified, series were underway with both painter and model reflected in a mirror. Two of the models, Yana Trevail and Janine Pecorini, were regular models, but his newest sitter, Benedikte Esbenson, had brought back powerful early memories of ‘her look-a-like Ria [Ney-Hoch]’, Lenkiewicz’s first adolescent love at the Hotel Shem-tov, the Hampstead home for Jewish refugees run by his parents. A painting of Ria which soon followed showed her Janus-like with two heads facing opposite directions, one uncannily like Benedikte. In Roman mythology, Janus faced simultaneously into the past and the future.

The Painter with Monca and Reuben. 1988. Oil on canvas, 157 × 161 cm

The Painter with Karen and Thaïs. 1988. Oil on canvas, 137 × 90 cm

A theme began to emerge as Lenkiewicz worked intensively on the paintings. On 5 July, his notes record:

Yana – do painting. Few painters can have done what I do in the way that I do it. Again she sat – heroically – worked very hard, made strong ‘Double’ study – the beginning of a series.

This was followed the next day with:

Janine – slowly talked her into sitting for a ‘Double study’. Worked, worked, worked so hard. Lively, sensual study.

The creative energy was returning and the ideas soon followed:

7 July – Much thought on theme of the ‘Double’ – the ‘Doppelgänger’ schlemazzle. Took from my shelves the studies by Timms/Irwin/Guerard/Rogers/Keppler/Vinge/Rank and Miller. Will re-read most of it and make sense of possibilities where the theme ‘Painter with Women’ is concerned.

In July, Lenkiewicz’s friend, the photographer Dr Philip Stokes visited Plymouth and recorded in his diary:

He [Lenkiewicz] told me too that the subject of the double, the ‘doppelgänger’, had interested him much lately, and that he was working on a small, intermediate exhibition around that theme. It would contain images largely of himself and other people, mainly women, and people would look at it as mere confirmation of their belief in his irremediable prurience. Since it is to be small as well as difficult, Robert wondered if he might hive it off into a small gallery somewhere, probably in New Street; thus avoiding unnecessary interruptions to the ‘Family’ Project.

The first paintings in the ‘Double’ series in Lenkiewicz’ studio in 1988 show (left to right): The Painter with … Janine Pecorini, Karen and Thaïs, Patti Avery.

Lenkiewicz in conversation with his model, Yana Trevail, during a sitting for a ‘double’ or doppelgänger theme portrait, 1988. Photo: Bjorn Grage.

When Benedikte cancelled a late night sitting at short notice, Lenkiewicz was infuriated. ‘I rage that mediocrity can look so beautiful’, he wrote in frustration, striking through his diary appointment which served to remind him: ‘Have large canvasses ready and mirror. Work hard – hard – hard – intense – intense.’

Instead of allowing ‘all that work and build-up to tonight’s painting’ to go to waste, he sat and ‘thought much in the library’. He decided to set up a canvas nevertheless, collected Karen Ciambriello and their newly born daughter, Thaïs, from their nearby home on the Barbican and recorded that:

Did full-size tonal study of the three of us – ‘Double theme’. Rich image – strangest of the three pieces so far. Much thought on enraging Project on the theme of ‘The Painter and Women’.

He was soon discussing a preview of the Project he was now calling The Painter with Women: Observations on the Theme of the Double, which would take place in New Street over the Christmas and New Year of 1988–89. Another more practical motivation was to resolve some of his perennial financial problems, as, to make matters worse, the Education Project had proved predictably uncommercial.

Double portrait of Yana Trevail shown at the New Street Gallery, 1988.

With the exhibition in mind, the pace of work rapidly increased. On 9 July, he noted, ‘Megan sits for erotica study. Work on Double theme.’ Then the following day, ‘Lindsay – Work hard on Double study. She was heroic – worked hard until early hours – Reasonable piece.’

By the time Stokes returned to Lenkiewicz’s studio in September, he was able to report:

He mentioned that the public attendance at the Education exhibition had now fallen low enough for him to think of closing it, and turn to concentrate on the small exhibition of doubles at the New Street Gallery … Robert led me into the bedroom, where there are a number of paintings of himself with various nude women, and one including Karen and Robert’s new daughter. Robert said Karen did not want him to use it, because of the possibilities of what might happen in the current moral climate … I was interested to see that as they now stand, the paintings will have a uniformly dark background.

On this visit, Stokes also photographed Lenkiewicz in his library, holding Jacques Derrida’s The Truth in Painting, revealing the artist’s growing interest in the concerns of postmodern philosophy, confirmed in the artist’s own diary:

Have now gone through thirty-one Wittgenstein books and eleven Derrida’s; and not seriously, credibly any the wiser. So very suspicious of any non-physiology based philosophy – though I love it. But then of course it must be all physiologically-based?

Rather than continuing to pursue his documentation of other people’s lives in his sociologically based Projects, Lenkiewicz was fixed on returning to a further ruthless analysis of his own relationships. Having recorded in minute detail his own aesthetic responses some ten years previously in the Mary: Aesthetic Notes large folio, it now occurred to Lenkiewicz that he could gather further evidence of his theory as to the physiological base of human behaviour from his partners. Stokes remarked:

Speaking about his relations with various of the subjects, Robert told me that he is now asking them to write down their experiences separately, and without reference to his own writings; indeed, preferably in ignorance of them. He brought out a box containing files of this material, and showed me examples, some of which so closely resemble his own work as to look like deliberate emulations.