Читать книгу Linmill Stories - Robert McLellan - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

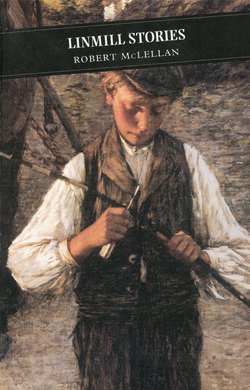

THE POWNIE

ОглавлениеLINMILL WAS A FRUIT ferm in Clydeside, staunin a wee thing back frae the Clyde road aboot hauf wey atween Kirkfieldbank and Hazelbank, close to Stanebyres Linn, ane ο the Falls ο Clyde the tounsfolk cam to see, drivin doun frae Hamilton in fower-in-haund brakes, whan the orchards were in flourish in the spring.

My grannie and granfaither bade in Linmill, and my minnie took me there for aa my holidays. I had been born there, my minnie said, and I wad hae been gled neir to hae left it, but that couldna be. My faither had his business in a toun.

It’s queer that I can hardly mind a haet aboot the toun whaur I bade in my bairnhood, whan I can mind ilka blade ο the Linmill grass. Ein whan I’m lost in the praisent, and the ferm seems forgotten lang syne, things like the taste ο a strawberry, or the keckle ο a hen whan it’s laen an egg, can bring the haill place back.

Juist the ither day I had a drink ο soor douk. That brocht the ferm back tae, for juist by the scullery door, on yer wey oot frae the kitchen, there was a soor douk crock wi a tinnie hingin frae a nail abune it, and whan ye wantit a drink ye dippit in the tinnie and gied the milk a steer, and syne helpit yersell. Syne ye syned the tinnie at the back entry, and pat it back on its nail.

I wasna juist shair ο that scullery. The ae winnock that gied it licht was sae smoored wi ivy that the place was eerie, and whan I gaed in for a drink ο soor douk I keekit ower my shouther aye for bogles, and whiles it was hard no to think that bogles were there, for there were twa hams and a roll ο saut fish hinging frae cleiks on the ceilin, and whan ye saw them black against the licht they were haurdly cannie.

But I couldna keep oot. There was a muckle bunker alang the waa neist the kitchen, for hauding pats and pans, and that had a raw ο drawers in it, and I wonert aye what was in them; and on the ither side, against the waa neist the stable, there was a wuiden stair, wi a press aneth it for hauding besoms, and that stair drew me tae. I gaed ower to the fute ο it whiles and lookit up, but there was nocht to be seen. It was as black as the inside ο the press aneth it, and that was as black as nicht.

Ae wat day, it was on an Easter holiday, I was sittin by the winnock at the back ο the kitchen lookin oot on the closs, feeling gey dowie, for I wantit to be oot and aboot wi my grandfaither, and my grannie wadna let me. The closs was dowie tae, for there was naething to be seen bune draps ο rain jaupin aff the causies, and the hens in the cairt shed at the faur end, roostin on the tail brods ο the cairts, and giein a bit girnie keckle whaneir ane ο them wantit a wee thing mair room, and tried to dunch its neibors ower a bit.

I had gotten tired watchin the hens, and was thinkin ο turnin roun and askin my grannie to let me mak a wee scone at the side ο the brod, for she was bakin, whan I heard the dug barkin at the closs mou, and my grandfaither cam in frae the yett. My hairt gied a lowp, for I thocht he micht be comin inbye and wad let me play wi his watch, but he lookit up at the lift for a while and syne gaed into the stable. I turnt to my grannie.

‘Can I gang oot to the stable, grannie?’

‘Bid whaur ye are. The horse wad kick ye.’

‘My grandfaither’s there.’

‘He’ll be ower thrang to bother wi ye.’

‘I waad staun at the door.’

‘Content yersell. Yer grandfaither’ll be in for his tea sune.’

I was gey near stertin to greit whan the ootside door ο the scullery opened, and I heard the clump ο my grandfaither’s buits. I ran through at ance to get a lift on his shouther, but he wasna for comin ben. He had gane to ane ο the bunker drawers. My een fair gogglet.

‘What are ye lookin for in there, grandfaither?’

‘A gullie.’

‘What for dae ye want a gullie?’

‘I’m mendin the harness for ane ο the cairts.’

‘Can I watch ye?’

‘Ay, ay.’

‘What else is there forbye gullies?’

‘Juist odds and ends.’

‘Can I hae a look?’

‘Na, na, ye’ll taigle me. Come on, I’m gaun up to the bothy.’

He shut the drawer and turn to the fute ο the wuiden stair. I was puzzled a wee, for aa the bothies I kent ο were the barn and the garret abune the milk-hoose, whaur the Donegals and their weemen-folk sleepit in the simmer whan they cam to pou the strawberries.

‘What bothy, grandfaither?’

‘The bothy up here.’

I keepit weill ahint him, for I was feart. My grannie had aye telt me there was a bogle up the stair.

‘Is there a bothy up there?’

‘Ay, for the kitchen lassies, but we dinna hae ony nou.’

I kent that, for it was Daft Sanny that gied the help in the kitchen.

‘Had the kitchen lassies flaes?’

I was still feart to follow, because I had aye been telt no to gang near the ither bothies for fear ο flaes.

‘Na, na, come on up.’

I gaed up the first wheen steps wi my hairt dingin, but whan I had taen the turn to the richt I felt no sae feart, for my grandfaither had opened the door at the tap, and through it I could see a bricht wee garret wi a bonnie paper on its was, aa yella roses like the anes my minnie had plantit roun at the front whan she was a lassie.

I followed my grandfaither in, and lookit roun, haudin on to the tail of his jaiket just in case. But I had nae need to fear. It was a lichtsome wee room: bare a wee, for the two built-in beds werena made up, and there wasna a stick ο plenishin. I likit the sky licht, though, and the paper wi the yella roses, and wonert if my grannie wad let me come up nou whiles and play at hooses. Then I gat roun fornent my grandfaither and saw that there were twa sets ο harness hingin frae airn cleiks aside the door. He was takin the bit aff ane ο them, a coorse cairt-horse set, but I didna pey muckle heed. The ither set had taen my braith awa.

It was like toy harness, it was that wee, and it had sic a polish on it ye wad hae thocht it was new frae the saiddler’s. The brecham and blinkers had a gloss like my grandfaither’s lum hat, and the rings for the reyns glissent like siller. The reyns themsells were sae delicate ye wad hae thocht they couldna haud.

‘What harness is that, grandfaither?’

‘It was harness we had for yer mither’s pownie.’

‘Had my minnie a pownie?’

‘Ay.’

‘Whan?’

‘Afore she mairrit yer daddie.’

I began to wish she hadna mairrit my daddie.

‘It maun hae been gey wee, the pownie.’

‘Ay, it was wee.’

‘Was it a sheltie?’

‘Ay.’

‘What did she drive it in?’

‘The bogie.’

‘Bogie?’

‘Ay, it’s in the cairt shed.’

‘I haena seen it.’

‘I wadna woner. It’s awa at the back.’

‘What’s it like?’

‘It’s juist a bogie. A wee kind ο cairt affair for gaun jauntin in.’

‘Juist like the gig?’

‘Na na, the twa saits are ower the wheels and rin back to front, an there’s a wee door in the back, wi an airn step up to it.’

‘Can I see it?’

‘Ay, if the rain’s aff. Come on and we’ll see.’

I followed him doun and oot through the scullery to the back entry, whaur the pails ο clean watter stude that Daft Sanny cairrit frae the waal. The rain wasna bad. He gied a cry to my grannie.

‘I’m takin Rab oot to the shed.’

‘Aa richt, but see he doesna get wat.’

‘Ay, ay.’

We crossed the wat closs and gaed ower amang the hens. They flew awa skrechin to the midden and left the shed fou ο feathers. My grandfaither gaed through atween the cairts and shiftit the reaper to mak a wey for me. Syne he shiftit the big wuiden plew that he used in the winter for clearin the snaw aff the roads. I hadna seen it for a gey while, for Yule had been green that year. He had an unco job, shiftin that plew, but in the end he gat it oot ο the wey and telt me to come on. It wasna easy to see at the back, for the stour in the place wi the hens aye scartin ticklet my nose and gart my een watter, but I gropit my wey ower aside him and felt for his jaiket tail.

‘That’s it, then.’

I blinkit like a bat. I could mak oot naething.

‘I canna see it.’

‘There, see, fornent ye.’

I gied my een a dicht and lookit hard, and shair eneuch there was the bogie. It was juist like ane I had seen afore at Fred Jubb the horse-brekers, whan he was brekin in shelties, but Fred had caaed it something else. He was an Englishman, Fred, and haurdly used oor names for onything.

It was ower daurk for me to see the haill ο the bogie, but by the wheels it was gey wee, juist a match for the harness in the scullery bothy. I lookit up at my grandfaither.

‘Could ye no pou it oot into the closs, Grandfaither, and let me hae a richt look at it?’

‘Na na. I wad hae to shift the haill shed.’

‘But I want to gang inside and let on I’m drivin it.’

‘It’ll be aa stour. I wad hae to wash it. I’ll fetch it oot efter, mebbe.’

‘Whan?’

‘Seterday comin.’

‘But that’s a haill week, nearly.’

‘Ye’ll hae to content yersell. I’m ower thrang the nou. I’ll hae to gang to the stable.’

‘Let me come tae.’

‘Na na. Awa back to yer grannie.’

I tried no to greit, but my een were wat afore I gat oot ο the shed, and whan he made for the stable I stertit to bubble. He turnt and liftit me.

‘Dinna greit, man. Dicht yer een wi that.’

He gied me his big reid spottit hankie and cairrit me ower to the stable.

I sat on the cornkist aside him while he gaed on wi his wark. I was feart to speak in case he wad send me back to the hoose again, but efter a while he stertit himsell.

‘It’ll be a guid bogie that yet. It was gey near new whan we bocht it, and it hasna been ill used.’

‘Did my minnie drive it aa by hersell?’

‘Ay. She gaed to Kirkfieldbank in it for the messages.’

‘Whaur did her pownie gang?’

‘We selt it.’

‘Could ye no buy it back?’

‘I dout no. I dinna ken whaur it is nou, and it’ll be gey auld.’

‘Could ye no buy anither?’

‘Ye’ll hae to speir at yer grannie aboot that, I dout.’

‘Can I speir at her nou?’

‘Ay ay. Awa wi ye.’

I ran roun and back into the kitchen. My grannie wasna in and there was a smell ο scones burnin. I ran through into the lobby. She was at the front door wi Willie Mitchell, the packman frae Kirkfieldbank. He had his big black boxes open on the step and was tryin to coax her to buy a dickie. My grandfaither wore a dickie at the kirk.

I poued at her apron.

‘Yer scones are burnin, grannie.’

‘Mercy me, I had forgotten them!’

She ran awa back in. Willie Mitchell pat back the dickies and liftit oot a wee broun guernsey.

‘Hou wad ye like that, Rab?’

I gied him a guid glower. I didna like him. Afore Yule he had selt my grannie twa pairs ο thick worsit combinations for me, pink like my grandfaither’s drawers, and they were that itchie they had speylt my haill holiday.

‘I hae aa the guernseys I need.’

‘Ye haena ane like that.’

‘I dinna want it.’

I turnt and gaed up the stairs to the landin, oot ο his way, and syne into the paurlor. That was anither place I couldna keep oot o, for there was a gless case there abune a kist ο drawers wi a tod in it staunin on a stane, and aneth there was a rabbit, lookin gey feart, and ahint the rabbit a weasel wi a bad look in its ee. I wantit aye to hit the weasel ower the back wi a stick, but I wad hae broken the gless.

I dinna ken hou lang I stude in the paurlor, but afore I cam oot I had forgotten the weasel athogither, and was thinkin ο the harness, and the bogie, and my minnie’s pownie. I keepit wishin Willie Mitchell hadna come alang and speylt my grannie’s bakin.

I heard the front door shut and gaed ower to the winnock. The packman gaed doun the Stanebyres side ο the front orchard and took the Clyde road for the Falls. I creepit doun the stairs and back into the kitchen. My grannie was rollin anither scone.

‘Grannie?’

‘Awa and play. I’m taiglet.’

‘I want to ask ye something.’

‘Awa and play, I tell ye!’

I didna like her whan she spak like that. It aye made me want to gang hame to my minnie. But I didna greit. I gaed into a corner and had a wee dwam, and in the dwam I drave the bogie to Kirkfieldbank for the messages, the same as my minnie had dune.

Whan my grandfaither cam in for his tea my grannie was still crabbit, and I didna daur speak, and efter we had aa dune I was putten to my bed in the truckle by the kitchen closet, and whan the lamp was lichtit I gaed to sleep. Afore I dozed aff, though, I heard him say in he was gaun to Lanark in the mornin to the mercat to buy a quey in cauf, and she telt him to be shair and no come hame fou. He was queer whan he was fou, my grandfaither, and my grannie aye yokit on to him, but I likit him fou weill eneuch, for he aye gied me bawbees.

It was wat the neist day again, and I had anither dowie time ο it, inbye, playin wi this thing and that and aye turnin tired ο it, and wonerin whan my grandfaither wad come hame. Sanny and the ither daft men had their denner at the side table and gaed awa oot to saw wuid in the auld byre again, and still he didna come, and my grannie and I sat doun to oor kail withoot him, my grannie wi her lips ticht, for she was beginnin to ken he wad be fou.

It faired whan we had feenished and I grew cheerie, for I kent that gin he was fou I wad hae siller to ware, and I thocht that gin it bade fair I micht be alloued alang to the shop at the Falls for a luckie-bag. I gaed doun the Kirkfieldbank side ο the front orchard and played at the road-end, aye lookin oot for him, but there was nae sign ο him aa efternune, and I gaed through the hedge into the orchard and huntit for auld nests I had kent in the simmer. Syne my wame began to rummle and I gaed inbye and priggit at my grannie for a piece.

She was in gey ill fettle by that time, and flytit me sair for the glaur on my shune, but she spread me a haill muckle scone wi reid-curran jeelie. And nae suner had she haudit it ower than my grandfaither cried my name frae the back entry, and we baith kent by his cry that he was fou by the ordinar.

I didna rin oot, for I didna feel shair ο him, and truith to tell whan he cam in frae the scullery he had a look in his ee like the lowe of a caunle. He stachert forrit and pat oot his haund.

‘Gie me yer piece, Rab.’

I took haud ο my grannie’s apron and grippit my piece ticht, but he played grab at it and poued awa hauf o it. Syne he gaed to the door and held it oot, and in cam a wee black sheltie.

He had bocht me my pownie.

I lookit to my grannie for fear she wad be mad, but the sheltie was sic a bonnie wee craitur, and sae dentie wi its piece, that she hadna the hairt.

‘Ye muckle big sumph,’ she said.