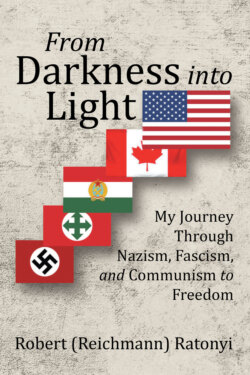

Читать книгу From Darkness into Light - Robert Ratonyi - Страница 8

ОглавлениеJourney 1: A Holocaust Childhood

There are two objectives in telling the Holocaust story. First, I wanted to write about my own experiences as a seven-year-old child. Second, I wanted to use this opportunity to provide insight into the larger scope and context of the European, specifically the Hungarian, history of the Holocaust in order to put my own family experiences into the proper perspective. In fact, I feel that the “big picture” may be even more important than my own experiences. What happened to our family of Hungarian Jews living in the center of Europe during what was considered an enlightened era of the twentieth century was nothing unusual or exceptional. If anything, the fact that I am alive to write this story is the exception.

My family’s situation in 1944 was an inevitable result of the downward spiral that started as far back as January 30, 1933, when Hitler became chancellor of Germany. It culminated in the annihilation of close to six hundred thousand Hungarian Jews, starting in early 1944 and ending with the liberation of Hungary in April 1945.

The Holocaust consists of the vast scale of Nazi eliminationist anti-Semitism in Europe that encompassed more than twenty countries, from the Mediterranean in the north to the Baltic Sea in the south, from France in the west to close to Moscow in the east. It begs the question of how this predominantly Christian region of about 500 million people could stand by and at best ignore and at worst actively collaborate in and support such a murderous empire. Six million men, women, and children, more than half of the European Jewry, perished during the Holocaust.

Even though Germany lost the war before completing its Final Solution,1 Hitler came close to eliminating Jews from Europe. Following the end of the war, three of every four, around three million, of the surviving Jews left Europe for North America, Palestine (now Israel), South America, the United Kingdom, Australia, and South Africa. Jews used to represent a significant percentage of the population of Europe (Poland, 10 percent; Hungary, 6–8 percent; depending on which borders are used). Today, Jews represent a miniscule percentage (less than 1 percent) of each country’s population. The largest population by percentage is in France due to the circumstances of the German occupation of France.2

When I think of the flight of the Jewish intelligentsia in the 1920s and the 1930s, followed by the obliteration of six million Jews through 1944, then the mass exodus of the survivors from Europe, I have to believe that Europe will never again be a hospitable place for Jews. Sadly, many of the European impulses that led to the Holocaust still exist today. Anti-Semitism is rampant in Europe, and it shows its ugly side not only in the ordinary street crimes committed by its perpetrators but also in the political and social expressions of some of its popularly elected leaders.

I tried to develop a statistical summary of the Jewish population by country prior to the Holocaust, immediately after it in 1950, as well as in 2017, in order to provide a more succinct and visual view of the impact of the Holocaust on the Jewish people. The best I was able to do is located in Appendix A.

According to Yad Vashem,3 the Holocaust started in 1933 when Hitler came to power. The killings did not just happen suddenly, by one single maniac or by any of the governments involved. Instead, the killings were the result of a legalized process of singling out the Jews and denying their civil rights. Laws were passed that gradually denied the Jews their freedom of occupation and education, of movement, of their ownership rights and their participation in any form of labor, and of civic or cultural organizations. The writer Daniel Jonah Goldhagen4 correctly identified the deliberate effort by the Nazis to dehumanize and demonize Jews (and the Roma people) to make it legally, morally, and emotionally acceptable to murder them.

Jews were fairly well assimilated into Hungarian society in the early 1900s. They were accepted as citizens in all professions, including academia and the Hungarian armed services. This moderate view of accepting Hungarian Jews as ordinary citizens who practiced a different religion from the Christian majority changed drastically in the 1930s. At the end of the decade, the Jews were portrayed as a dangerous “race” whose members committed unpardonable crimes against Christianity, and whose very presence in society had endangered the economic, social, and political well-being as well as the morality of the Christian population.

Discrimination against Hungarian Jews in the twentieth century started with the Numerus Clausus law, Latin for “limited number,” enacted on September 20, 1920. It declared that from the 1920–21 academic year onward, only those would be admitted to universities and colleges “who were trustworthy from the point of view of morals and loyalty to the country, and even those only in limited numbers [the maximum percentage was fixed at 6 percent], so that thorough education of each student could be ensured.”

The term “Jew” was deliberately omitted, and there is no trace of anti-Semitism in the law, yet it closed the gates of the universities to many Jews. Instead of abilities, it was “loyalty to the country,” i.e., birth and background, that determined who may attend university. In today’s lingo, this was a “politically correct” way of discriminating against the Jews. Soon after Hitler was named chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, discrimination, isolation, deportation, and the eventual liquidation of Jews spread from Germany to the occupied lands and eventually to Germany’s allies, including Hungary.

The year 1938 was an important year for me, for my parents, and for the Jews of the Third Reich. I was born in January of that year. Subsequently, two historic events took place. On March 13, 1938, Germany invaded and annexed Austria into the Third Reich in what was called the Anschluss in German. Some 97 percent of Austrians voted for the Anschluss, and Hitler was cheered by hundreds of thousands of Viennese when he entered the city following the annexation.

Furthermore, the second historic event took place in November 1938. The official start of the Holocaust is recognized as the year 1933 when Hitler came to power. However, for me personally, it was Kristallnacht, referred to in English as “The Night of the Broken Glass,” that occurred on November 9 and 10. This was a massive coordinated attack on Jews carried out by Nazi storm troopers who were aided by local police and citizens. Gangs of Nazi youth roamed through the Jewish neighborhoods of both Berlin and Vienna, capitals of Germany and Austria, respectively, in addition to hundreds of other cities in the Third Reich. During the two days of riots, about twenty-five thousand Jewish men were sent to concentration camps where they were brutalized by SS guards, and some of them beaten to death. The Nazis recorded 7,500 businesses destroyed, 267 synagogues burned, and 91 Jews murdered. Part of my family and I lived in Budapest, less than 175 miles from Vienna, where the news of Kristallnacht was known within days if not hours.

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, which started World War II. Hungary then joined Germany as an ally in June 1940, which most likely delayed the execution of the Final Solution there until 1944.

The conclusive chapter of the European Holocaust commenced on January 20, 1942, when Reinhard Heydrich, Himmler’s second in command of the SS,5 convened the Wannsee Conference in Berlin. As a result, fifteen top Nazi bureaucrats officially approved the coordination of the Final Solution, under which the Nazis aimed to exterminate the entire Jewish population of Europe. The whole meeting took no more than an hour, and the translation of the minutes is no different from that of a board of directors meeting of a large corporation taking care of ordinary business matters.6 The records and minutes of the meeting were found intact by the Allies at the end of WWII and were used during the Nuremberg Trials. Heydrich personally edited the minutes of the meeting, utilizing the following code words and expressions when describing the actions to be taken against the Jews:

“…eliminated by natural causes” refers to death due to a combination of hard labor and starvation, the cause of my father’s death.

“…transported to the east” refers to mass deportations to the planned gas chamber complexes such as Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz.7

“…treated accordingly” or “special treatment” or “special action” refers to execution by SS firing squads or death by gassing.

At the time of the Wannsee Conference, I had just turned four years old, but my, and my family’s fate were sealed according to those minutes. The potential difficulty the Germans were facing with the liquidation of the Hungarian Jews (742,800 listed in the minutes of the Wannsee report) is all mentioned within the minutes. It was agreed that in order to deal with the Hungarians, “it will be soon necessary to force an advisor for Jewish questions onto the Hungarian government.” The special handling was necessary because of Hungary’s status as an ally.

The process of isolating the Jews and stripping them of most civic, political, social, and economic rights did not begin in Hungary until 1938. Under pressure from Germany, as well as from internal anti-Semitic forces, the Hungarian parliament began passing anti-Jewish laws in the spring of 1938, similar to those passed in Germany five years earlier. A detailed chronology of the most important events of the Hungarian Holocaust is included in Appendix B.

By April 1942, the Hungarian government promised the “resettlement” of close to eight hundred thousand Jews but not until after the war. Doubts about the outcome of the war and the consequences for Hungary began to emerge within Hungarian ruling circles. In my opinion, Hungary’s reluctance to execute Hitler’s Final Solution was not so much due to the moral dilemma of killing its Jewish population but more to the cynical and self-serving concerns about losing a highly educated, creative, and productive segment of society, together with the anticipated postwar retributions.

By 1942, the Hungarian government had doubts about a Nazi victory, and Hungarian Jews were hopeful until 1944 to escape the fate of their European brethren. Indeed, had it not been for Adolf Eichmann’s8 personal intervention in Hungary and the installation of a pro-Nazi, anti-Semitic government on March 22, 1944, Hungarian Jewry might have survived the Holocaust. As it turned out, close to one of every ten Jews killed during the Holocaust was an ethnic Hungarian Jew.

The gross statistics and many dates shown in Appendices A and B can be overwhelming and also overshadow the individual and personal tragedies they depict. Therefore, I compiled six pictures shown on page 9 with the caption “Pictures from Auschwitz” to focus on the individual tragedies. These pictures illustrate the fate of 400,000 of the nearly 440,000 Hungarian Jews, including many in our family, who died in Auschwitz. Reading the statistics and the chronology of events in Appendices A and B and looking at these pictures from Auschwitz may be a shocking and mind-blowing experience for my children, grandchildren, and future generations. However, it is necessary to endure the pain of learning the history of their ancestors in order to keep these memories alive. The lessons of history are clear, and I invoke the warning of George Santayana9: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I was born on January 11, 1938, just a few months before the Hungarian parliament ratified the First Anti-Jewish Act. The Soviet Army liberated the Budapest Ghetto,10 where I survived the last few weeks of the war, on January 18, 1945, exactly one week after my seventh birthday. Therefore, my first seven years on this earth coincided with the Hungarian Holocaust period. Most adults have childhood memories that extend back before the age of seven. Strangely, my memories of those childhood years with my family and friends are mostly gone, except for memories associated with the Holocaust.

1. Pictures from Auschwitz.

The Yellow Star

2. I remember practicing my alphabet in this last family picture—circa 1943.

On January 11, 1944, I turned six years old, and soon after I first felt the profound impact of the Holocaust, even though this term was not in my vocabulary until decades later.

When I was four and five years old, I was not aware that my father’s absence was due to the anti-Jewish laws forcing him into special Jewish military units first and labor battalions later, where visitation rights to one’s family were rare. After Hungary became an ally of Germany in June 1940, a decree was passed in the Hungarian parliament on December 2, 1940, ordering Jewish men to enroll in special Jewish labor battalions. My father was twenty-nine years old. It is not clear when exactly my father joined a labor battalion, but it was probably between 1941 and 1943. I accepted that my father, unlike the fathers of Christian children around me, was absent without ever knowing where he was or why. This explains why even as I was growing up after the war, I could hardly recollect his face, much less remember a warm embrace, a bedside story, a smile, or a kiss.

I often wondered as I grew up why I didn’t have any brothers or sisters. After all, both of my parents came from very large families. My mother was the youngest of ten while my father was the second oldest of nine children. Only decades later when I had children of my own did I learn that my parents decided it was too dangerous to bring another Jewish child into their world.

I was already a father myself when I learned that the reason for my lack of siblings was directly attributable to the general condition of Jews in 1938 Hungary. My mother confessed that she did get pregnant at least once when I was two or three years old. According to my mother, my father told her, “I don’t want to bring another child into this world. If you don’t get an abortion, I will divorce you.” When my mother told me this, she was already an elderly woman, but there was unmistakable resentment and hurt in her voice when she told me that if it had been her choice, she would have had more children.

Subsequent events proved my father right. Based on my personal experiences during the critical period of May 1944 through the spring of 1945, I have little doubt that the chances of survival of a younger sibling would have been negligible at best. However, this is not an excuse or an apology for my father’s ultimatum to my mother. It is hard for me to believe that there was not a more delicate or sensitive way of conveying his convictions. On the other hand, it is also possible that my mother was a bit melodramatic in describing these events. Therefore, the first victims of my Holocaust were my unborn brothers or sisters. Consequently, I remained a single child, which has always been a regret of mine. This is why the beginning of the Holocaust was Kristallnacht for me.

Sadly, it seemed that my parents must not have had a warm and loving relationship. Since the disastrous times started just when I was born, it is possible that they didn’t have the chance to develop one given their short-lived marriage that began on December 4, 1936. In passing judgment, I have to bear in mind that back in those times marriages between children of very large families were not necessarily based on love but were more of an economic or socially driven necessity. My suspicion is supported by the fact that my mother had never divulged any romantic memories about my father. In fact, she hardly mentioned him as I was growing up other than to say that he was a good dancer, loved me very much, and was a strict father.

Therefore, unbeknownst to me, the Holocaust had a significant impact on my life before the age of six. Had it not been for the terrible times already on the horizon, I probably would have had some sisters and brothers. For the rest of my life, I felt envious of those who had siblings.

My naiveté regarding the consequences of being Jewish was shattered in early 1944, when Germany invaded Hungary in March. On the thirty-first, Eichmann personally traveled to Hungary to plan the deportation of Hungarian Jews. An order was issued for Jews six years and older to wear a six-pointed bright canary-yellow star that measured ten by ten centimeters (four by four inches) on the top left side of their clothing in public. I had just turned six in January and therefore had to wear a yellow star every time I went outside to play or go on an errand with my mother.

My mother didn’t observe any of the daily Jewish rituals, but she made sure that during the Jewish High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Passover, and Hanukkah, we went to my grandparents’ home to celebrate. In other words, it was clear that I was Jewish and different from most of our neighbors who were Christians, but I didn’t know exactly what those differences were aside from celebrating different holidays. Other than a few well-to-do Jewish families in our building, most of our neighbors were Christians.

Right next door to us lived the Gyura family, a married couple and their daughter, Juci, who was about my age. We got along well with them, and I recall being invited over to their place to see their Christmas tree with all the decorations. Mr. and Mrs. Gyura made sure that I also had a present. Their tree was decorated with all the colorful bulbs, angel hair, and candy hanging from the branches. Their tiny apartment was a mirror image of ours with their kitchen adjoining our own. The Gyuras were Protestants, not Roman Catholics. Protestants, who represented about 15 percent of Hungary’s population, were perceived as being more tolerant of Jews as opposed to their Catholic brethren.

One day, before the anti-Jewish laws concerning the Star of David and other restrictions were pronounced, my mother arranged a meeting through the Gyura family to meet their local pastor and discuss the possibility of converting me into the Protestant faith. Clearly, the news about the Hungarian Jews’ fate in other parts of the country had spread to the city. This was my mother’s last desperate attempt to provide protection for me. I do remember going into the small Protestant church at the corner of Fűzér and Kápolna Streets and the meeting with the minister, but nothing ever happened afterward. There were strict laws against converting Jews, and the penalties were severe: deportation and almost certain death. In addition, as I later learned, the authorities disregarded all such conversions. Escaping the Nazis was only possible through having money and/or connections to forge the proper papers and to pay off those willing to take the risk of being caught hiding a Jew, for which the penalty was death. My mother had neither money nor connections, so we waited for the inevitable.

Bearing the Jewish star in public raised my awareness of being Jewish to a new level. My mother and I had often recalled the bittersweet story of my Jewish friend Bandi Fleishmann, who was a few months younger than I. When Bandi saw me with my yellow star, he, too, wanted one. He cried bitterly and couldn’t be consoled by his mother’s explanation that he was too young to wear it. We children didn’t know that wearing the yellow star or not could mean the difference between life and death in the months ahead.

The year 1944 turned into an apocalyptic year for the Jews of Hungary. Due to my young age, I was spared the mental and physical agony and deprivation that were yet to come to the Jews of Budapest. Moreover, I had no inkling of the fate of Hungarian Jewry outside the capital of Budapest, where several of my aunts, uncles, and cousins lived. I’m not sure how much my mother knew either.

I learned that there was something unusual and dangerous going on in the world that the grown-ups called war. I had no idea of what this meant exactly except that my mother was visibly shaken and more and more anxious as time went on. Since March of 1944, when the Germans took control, Jews were exposed to arbitrary arrests and deportation.

It was in the late spring and early summer of 1944 when phase 1 of the Hungarian Final Solution was implemented. With lightning speed and great efficiency, approximately five hundred thousand—roughly two-thirds of Hungarian Jewish men, women, and children who lived outside Budapest—were dragged from their homes, jammed into cattle cars, and deported. Members on both sides of my family, which consisted of uncles, aunts, and cousins, were included.

Ninety percent of these Jews from the Hungarian provinces and smaller cities were sent to Auschwitz, and of those only 10 percent survived. It took less than sixty days to accomplish this. The deportations were enthusiastically supported by the local government officials, police officers, soldiers, and local population. Historic evidence revealed that even the Germans were surprised by how enthusiastically and ruthlessly the Hungarians supported and aided in this tragedy. My mother and my family who lived in Budapest, including my grandparents, knew that many in our family were deported. However, my mother kept me in the dark.

There were also nightly and daily air raids on Budapest, starting in the spring of 1944. The bombing of Budapest started on April 2, when the Americans bombed the industrial sites in the city during the day and the British by night. On July 2, the Allies delivered the greatest air raid against the city, this time including the residential areas. I do recall the air raid sirens going off in the middle of the night. My mother hurriedly dressed me to cross our courtyard and go into the cellar that ran underneath the length of the apartments facing ours.

Meeting some of our neighbors in the cellar during air raids was actually fascinating. I rarely, if ever, had the opportunity to socialize with those neighbors who lived in the beautiful and spacious apartments across the courtyard, except with the Lesko family, where I often hung out with Tibi, who was four years older than I. The courtyard separated the well-to-do middle-class families from the poorer, working-class families on our side of the building. A good example of this social divide was an older Jewish couple, Mr. and Mrs. Gergely, who lived right across the courtyard from us with their dog.

I rarely saw Mr. Gergely, who owned a retail store on the main road in our neighborhood. He came home every afternoon to take a nap. I was under strict orders, which I frequently violated, not to play outside and to avoid making any noise that might disturb his sleep. My mother and I were never invited to the Gergelys for a social visit that I can recall. However, Mrs. Gergely occasionally invited me in and showed me to their spájz, or “pantry” in English, to offer me a candy or a cookie that she stored in glass jars lined up on one of the shelves.

These social barriers miraculously disappeared in the cellar during the air raids. My mother chitchatted with the Gergelys and others as if they were part of her social circle. In addition, I received attention from people who under normal circumstances would barely acknowledge me. Everyone huddled in the darkness around the flickering candles. The whispers of the grown-ups were occasionally punctuated by the whistling noise of falling bombs followed by large muffled explosions.

In late June 1944, phase 2 of the Hungarian Final Solution was implemented. The Jews of Budapest were forced into approximately two thousand selected Yellow Star buildings in the city, which included ours. All the Christians living in those buildings had to move out unless they had special permission to stay so that Jewish families could move in. All I remember is that some of my Jewish friends and their mothers now lived in our building.

One Christian family who stayed in our building was Mr. and Mrs. Lesko with their son Tibi. Although we were neighbors, we lived a world apart. I loved hanging out at Tibi’s place. Mr. Lesko was an architect, whom I had rarely seen at home. Mrs. Lesko, a very tall woman, was always busy in her kitchen with her apron on. She was very nice to me and often invited me to join Tibi for lunch or a snack. Most importantly, I enjoyed spending time with Tibi whenever he would tolerate me. If Tibi was not home when I knocked on their door, I asked if I could look at their leather-bound collection of American comics that contained the original drawings and was translated into Hungarian. Thus, my first exposure to American culture came at a very early age.

It was in the early fall of 1944 that my mother had a chilling encounter with Mr. Lesko, an ardent Nazi. They accidentally met at the entrance of our house one day where Mr. Lesko warned my mother, “The day will soon come, Mrs. Reichmann, when you will be happy to be my servant and to polish my boots.” The obvious reference was to the eventual enslaving of all the Jews of Hungary. It must have been due to Mr. Lesko’s Nazi connections that his family was allowed to stay in our Yellow Star-designated building. It turned out that many years after the events of 1944, Tibi Lesko had an indirect role in my decision to escape from Hungary in 1956, but that is another story.

3. Swedish SCHUTZ-PASS issued to Éva Balog; August 19, 1944.

The day and night bombings were intense, but I don’t recall being particularly frightened. The worst time was when I had to go to bed. I insisted that the door to our kitchen be left open just a crack so I could see a little light and hear the whispering voices of my mother and her friends discussing the day’s events around our kitchen table. I listened to their conversation and occasionally picked up some foreign-sounding words like “Schutz-Pass,” which means “Protective Passport,” a document issued by the embassies of neutral countries, such as Sweden, Switzerland, and Portugal. Hundreds or even thousands of these or similar documents were issued to provide protection for Jews.

The Swedish Schutz-Pass shown above declares that “the abovenamed person is allowed to travel to Sweden,” which was quite laughable in the summer of 1944, since the only Jews traveling out of Hungary were in cattle cars going to Auschwitz. The document also states that until the abovenamed person can travel to Sweden, he or she can live in a place protected by the Swedish government. This is how holders of Schutz-Passes were allowed to move into several protected houses in an area of Budapest referred to as the International Ghetto, where they were relatively safe from the Nazis. Access to these passports was not easy and not free. Most Hungarians, including my mother, were not able to secure one for their families.

4. Canadian stamp honoring Raoul Wallenberg.

Swedish Schutz-Passes were issued by Raoul Wallenberg, the third secretary of the Royal Swedish Embassy, who was sent to Budapest in July 1944 to save as many Jews as he could. He is credited with saving the lives of thousands of Budapest Jews. The Canadian post office issued a stamp in his honor in 2003. The question mark at the end, “1947?” indicates that in 2003 we still didn’t know the fate of Raoul Wallenberg after the liberation of Budapest by the Red Army in 1945.

The advantage of being almost seven years old was that I didn’t quite understand the seriousness of the situation we faced. I was unable to comprehend that we faced a far more sinister danger than the possibility of a bomb directly hitting our building. However, the immediacy of being hit by a bomb became quite clear one day while in our cellar during a daytime air raid.

A very loud whistling noise was followed by a great thud, which was then followed by silence. When the “clear” siren was sounded, we scrambled up the stairs to see what had happened. A massive unexploded bomb fell right through the roof of the building and lodged in the floor of the second-story apartment. The top half of the bomb was inside the second-floor apartment, and the bottom half, with a pointed conical end, hung from the ceiling of the first floor. Had the bomb exploded, we might not have survived that attack.

In September 1944, I was eager to start first grade, but I was forced to stay mostly indoors, much of the time spent in our cellar. By this time, the world had been at war for years already, and millions of people, adults and children alike, had died in the killing fields of faraway places as well as in the Nazi concentration camps.

Having completed phase 1 of the Final Solution for Hungary at the end of July 1944, phase 2 was implemented for the remaining two hundred thousand or more Jews in Budapest, where my mother, grandparents, and I lived.

In order to accomplish the ultimate deportation of the Budapest Jews, orders were issued to herd all of us into a walled prison referred to as the Big Ghetto, located in the middle of Budapest, which was the destination for my mother and me.

There were very few options available to stay out of the ghetto. One was to pass yourself off as a Christian with false identification papers. Another possibility was to be hidden by a Christian family, and a third option was to obtain a Schutz-Pass.

Then, on October 10, 1944, we were awakened at dawn by someone banging on our door and yelling, “Everybody get out!” I was scared because I knew this was not a typical air raid since no sirens were heard. We quickly got dressed and joined the other Jewish mothers, children, and some of the older couples who lived in our building. There were several soldiers with guns on their back ordering the Jews to line up in the middle of the courtyard.

We stood in one line, my mother on my left holding my hand, when someone shouted, “All grown-ups, two steps forward!” I could feel my mother’s hand slipping from mine as she started crying, let my hand go, and stepped forward. As a result of the confusion and seeing my mother cry, I joined the weeping chorus of the other children. Then someone shouted, “Turn left and march!” and the row of women began to move toward our gate.

This all happened so quickly that I couldn’t comprehend what was going on. A soldier standing near me put his hand on my head and said, “Don’t cry, little boy, your mother will return.” However, his words, although prophetic, didn’t console me. I continued to cry and tried to hold my mother’s image in my mind through tearful, blurry eyes long after the last of the grown-ups had disappeared through our gate. This was the last time I saw my mother until the summer of 1945.

Survival

A friend of my mother’s, Julia, an elderly Jewish woman who moved into our Yellow Star house, had not been taken away with the other women. Julia decided to take care of me after my mother was taken away. Perhaps it was prearranged between my mother and her, or she simply took the initiative, but that very same morning Julia told me that she was going to take me to my grandparents’ apartment house in the city. I knew my mother’s parents well. My mother and I had visited Nagymama and Nagypapa, or “grandmother” and “grandfather” in English, every other week, so the idea of being with them was comforting.

As soon as the curfew was lifted, Julia packed up some of my belongings and took my hand to begin the long walk into the city to my grandparents’ house. I made sure that Julia packed my new white long pants, which children didn’t usually wear back then, most of us sporting shorts and knee-length pants. For me, my striking long white slacks were a testament to my being a grown boy and not a baby anymore.

Trips to my grandparents’ place were something I always looked forward to. My mother and I used to take three different streetcars to Lövölde Square, and then walk a short distance to 106 Király Street, located in a Jewish neighborhood in the central part of the city. Kneeling on the bench in the streetcar, I watched the houses go by along with the retail shops that had fancy colorful signs hung above the shops. I always tried to read the signs, having already known some of the letters of the alphabet that my mother had taught me. The streetcars hurtling in the opposite direction thrilled me as the faces in the windows whizzed by at what seemed an incredibly high speed.

Nevertheless, this trip with Julia on October 10, 1944, was very different. The damage to Budapest was significant. Buildings had disappeared where the bombs fell, only rubble remaining. Walls stood without roofs and buildings without facades, exposing floors with furniture and whatever evidence of previous occupants remained. The streetcars weren’t running at that time, and we had to make the long journey on foot, by far the longest I had ever taken in my short life.

I recollect fragments of our trip and remember having been fascinated by what I saw. The two of us, an old lady who could have been my grandmother and I with yellow stars on our coats, walked through rubble, torn pavement, pieces of fallen airplanes, and broken vehicles left on the streets in the aftermath of the heavy bombardment on the city. It must have taken several hours for us to get to my grandparents’ place given our respective ages.

Distracted by the excitement generated by the strange sights around me, I forgot to think about my mother’s strange disappearance earlier that morning. I felt safe with Julia holding my hand and knowing that soon I would be with my grandparents, who loved me and always welcomed me in their home.

Another reason I looked forward to visiting my grandparents was that their building was several stories high. It was a large contemporary building by the standards of those days. Once we passed through the main gate, we walked up several steps that led directly to the elevator in the middle of the foyer. However, I was disappointed in never having an opportunity to ride it as my grandparents’ apartment was on the main floor.

I also enjoyed the spaciousness of their apartment. Unlike our tiny two-room apartment, this place had a foyer, a bathroom, a separate toilet, several large rooms, and a very large kitchen. It even had a maid’s room, though I can’t recall ever seeing a maid there. They also had a large icebox in the foyer, a rarity in our neighborhood and where I learned that certain food items like butter and milk were kept in.

5. The Spitzer family. My mother is the youngest girl next to my grandmother. The picture was probably taken around 1930 when my mother was fifteen years old.

My grandmother was a sizable woman, taller than my grandfather. She had a round face and sad brown eyes that betrayed her smile, and she would often take me into her broad lap. Born as Ida Glück in 1888, Mamuka, as all her children called her, was fifty-six years old in 1944. She had ten grown children, five boys and five girls, and was grandmother to twelve.

Born as Vilmos Spitzer in 1881, my grandfather turned sixty-three in 1944. In contrast to his wife, he was short and thin, probably not taller than five feet, two inches. As a child, I was fascinated by his handlebar mustache that was curled upward, ending in a sharp point, giving his face a serious martial look. I still remember playing with his mustache while sitting in his lap.

Now I have to pause in telling my story in order to introduce a “story within the story.” I had already completed the draft of this story in the fall of 2004 when I called my Cousin Miklós Grossman in Sydney, Australia, to say hello and inquire about how he and his family were doing. Miklós and his younger brother Tomi are my first cousins. Their mother, my Aunt Piri, was one of my mother’s older sisters. How my cousins and their mother got to Australia from Hungary is another inspiring tale, but outside the scope of my own.

During my conversation with Miklós, I mentioned that I had written down my experiences of the Holocaust and complained to him that there were many holes in my story. I told Miklós that I could vividly remember many vignettes of my experiences, but I was having difficulty putting all the events together. Here is a brief excerpt of our phone conversation:

Me: I remember many things, but I am missing many details.

Miklós: I remember everything!

Me, after a long pause: What do you mean? Were you there?

Miklós: Of course I was there. So were my brother Tomi and our mother. We were all together with our grandparents.

Me: Why don’t I recall any of this?

Miklós: You were too young and were probably confused.

6. Aunt Piri after she turned ninety in 1999 in Sydney, Australia. My cousins, Miklós on the left and Tomi on the right.

I have to add that Miklós was seven years older and Tomi was about three years older than I. Therefore, in 1944, Miklós was already fourteen years old and was able to retain all that we had gone through together. On the other hand, Tomi can recall even less than I can, which I will return to later.

I was shocked to discover that exactly on the sixtieth anniversary of the events that took place in October 1944, my Aunt Piri and my two cousins were with me during those horrible times. All these years thinking about Julia taking me to my grandparents’ house, I failed to remember them, on which my mind is completely blank to this day.

In my excitement, I started asking random questions, which Miklós dutifully answered with all the necessary details. Finally, we agreed that I would call him back and spend more time on the phone to add many of the missing details. My second phone call to Miklós provided a wealth of information about how our little band of family survived the ensuing months in the belly of the beast.

Unfortunately, Miklós had developed emphysema, the result of a lifelong smoking habit, and his health was declining. That, plus the difficulty of discussing events that took place sixty years ago in English and Hungarian over a satellite connection to Australia, made it difficult for me to accurately capture all the information I wanted to. Therefore, following my second phone call, I decided to travel to Australia in December 2004 to hear Miklós’s recollection of events face-to-face. I captured several hours of conversations with Miklós on tape and have incorporated much of it in this story.

I have no recollection of what happened once I arrived at my grandparents’ house on the day, or possibly the day after, my mother was taken away. I can only speculate that the usual warm welcome was replaced by sadness once my grandparents found out what happened to their youngest daughter. By this time in mid-October 1944, my grandparents must have known that their other children who were not present, as well as their respective families—husbands, wives, sons, and daughters—had been taken away to various forced labor and concentration camps.

Now there were ten of us living in my grandparents’ home. In addition to my grandparents, there was me, Aunt Klári and her paraplegic son Iván, and Aunt Piri and her two sons, Miklós and Tomi. Due to the overcrowding, I shared a bed with one of my aunts. In addition, there was a couple I never met, older than my grandparents, whom I later discovered were my grandfather’s older brother Samuel and his wife. Before going to sleep at night, I missed my mother terribly.

Unfortunately, my sense of safety and security with my grandparents and extended family didn’t last long. Shortly after my arrival, I learned that we had to pack up and move. Of course, I had no idea why or where we were going, but as long as I was with my family, I wasn’t afraid.

The final relocation of the Budapest Jews into designated Yellow Star houses was about to be completed, and the house where my grandparents lived on 106 Király Street was not a Yellow Star house. Therefore, we had to move.

Throughout our dangerous journey from house to house in the ghettos to liberation by the Soviet Army, our fate was in the hands of a man I didn’t even know existed, according to my Cousin Miklós. This man was our guardian angel, my mother’s Cousin Laci Spitzer,11 who single-handedly aided us through the terrifying weeks and months ahead and possibly saved our lives.

László Spitzer, Laci for short, was the oldest of three brothers, the sons of my grandfather’s older brother Samuel and his wife, Eszter. I knew all three brothers, Laci, Pali, and Imre, and their families rather well much later in life in Montréal, Canada. However, back in Budapest in 1944, I was unaware of their existence.

Laci was a large man with blue eyes and not a trace of “Jewishness” in his features. He was also what we would call a tough guy. He somehow managed to get an Arrow Cross12 uniform and false identity papers for himself. His sole purpose in life in 1944 and 1945 was to save himself, his brothers, and his parents from death. Because his parents were quite old, he asked his uncle, my grandfather, to allow his parents to join us and to care for them. In return, he promised to help the rest of the Spitzer family, now all living at my grandparents’ place.

His plan was to secure (probably forged) Swedish Schutz-Passes for his parents, my grandparents, my two aunts, and their three sons, which added up to nine Schutz-Passes. Of course, he didn’t know that I joined the family and now needed ten Schutz-Passes. In the end he was able to produce eight of these documents, leaving us two short. Even though they didn’t have one, my grandparents made sure that I did. As it turned out, just a few weeks later, my grandparents’ not having the Schutz-Passes almost cost them their lives.

The house Laci picked for us was in an area of Budapest that became known as the International Ghetto on the east side of the Danube, across from Margaret Island. The name International Ghetto came from the fact that it was where all the “protected houses” supported by various foreign embassies were located. The Hungarian government reached an agreement with the embassies of neutral countries, such as Sweden, Switzerland, and the Vatican, that all Jews with protective documents or affidavits issued by these governments would be temporarily protected as long as they lived in specifically designated houses.

7. Locations of the Big Ghetto and the International Ghetto.

These affidavits testified that the holders of these documents were approved to immigrate to the issuing neutral country as soon as it was feasible. There were at least fifty of these designated “protected houses” in the International Ghetto. This area also happened to be where many of the well-to-do Jewish families lived, and for that reason, many of them were designated Yellow Star buildings.

There were important advantages of moving into a protected house as opposed to into the Big Ghetto. First, these houses were not walled-off prisons. There was freedom of movement in and out of the protected houses to buy or barter for food and medicine, visit family, or go to anywhere when the curfew for Jews was lifted. And most importantly, Jews could keep money, jewelry, and all valuables they could carry.

In order to bring us all together under one roof, Laci arranged to have an apartment available for us in a building where his girlfriend, Erzsi, who later became his wife, lived. The house was on Légrádi Károly Street, known today as Balzac Street, and we all moved into a third-floor apartment. Laci deemed this place safe, and the fact that the building’s superintendent, a woman, was not an anti-Semite was definitely favorable.

It was quite the frenzy as my grandparents and aunts tried to decide what to pack, what to take, and what to leave behind. Food, sheets, blankets, pillows, clothing, eating utensils, precious family heirlooms, among many other things, had to be sorted out. Arguments ensued as to what was feasible to carry. A wicker basket normally used for shopping at the market was assigned for me to carry. Additionally, a cast iron meat grinder that looked enormous to me was placed in the basket and was topped off with some of my clothing that Julia had brought with us, including my precious pair of white pants.

To this day I cannot figure out why grandmother insisted on taking the meat grinder. The whole city was starving, and even potatoes and bread, never mind meat, were scarce. But no matter how bitterly I complained about the weight of the meat grinder, Grandmother insisted that I carry it. And that is how our journey to seven different places during the course of the next few months began.

So, one day, all ten of us, including Laci Spitzer’s parents, packed up with bundles of property; me with the meat grinder and Cousin Iván in his wheelchair with bundles in his lap, began a journey on foot from one place to the next that I shall never forget.

Our building, 106 Király Street, from where we started, literally bordered the northern perimeter of the Big Ghetto. The distance from there to our new destination was a good mile or mile and a half of walking.

More than sixty years after these events took place, I still have this bittersweet recollection of a feeling of indignation for having to carry the heavy meat grinder in spite of my protestations. What had my grandparents or aunts been thinking? Did they think that they could set up a functioning kitchen or have access to one in some stranger’s apartment? Did they think that they could actually obtain meat for cooking?

Looking back, I can only conclude that the grown-ups didn’t have a clue to the conditions we were about to experience once we left my grandparents’ place. Nevertheless, I had to carry my heavy cargo without it ever being in any proximity of meat to grind in the months ahead.

Life was still dangerous for Jews despite having authentic papers to authorize living in a protected house. Our goal was to stay one step ahead of deportation or being gathered together for summary execution on the banks of the Danube. Our survival depended on obtaining sufficient food to avert starvation, on avoiding any serious illness or the arbitrary roundup of Jews by the Arrow Cross, and on not being bombed by the Allies. It was a race against time as the fighting was already at our doorstep and the Soviet Army was rapidly approaching Budapest from the east.

It was on Légrádi Károly Street that my grandparents were caught without their papers. The Arrow Cross men periodically visited the protected houses and demanded to see everyone’s papers. We all had to descend to the courtyard and stand in line as the papers were examined. Since my grandparents didn’t have any papers, they were told to take whatever they could carry in one bag, and were taken away to the Budapest brick factory, which was a collection center for future deportees. The sudden departure of my grandparents was disastrous for all of us.

Miraculously, two days later at daybreak, my grandparents were spotted from our window walking back toward our house, pulling their knapsack behind them in the snow. Somehow my grandfather managed to engineer their escape before dawn and we were together again. Following the near-fatal incident with my grandparents, we moved out of the house where the grown-ups had felt relatively safe for the previous couple of weeks.

I recall nothing peculiar about our stay at Légrádi Károly Street, our first stop. We still slept in beds, the apartment had windows to keep the cold out, and I didn’t feel hungry. I still missed my mother a lot. I certainly didn’t have any idea that by this time my mother, together with several thousand Jewish women, would be marching on foot toward Austria under the most miserable and inhumane conditions.

I learned much later that after our separation on October 10, 1944, my mother was taken to a brickyard in Óbuda, an old section of Budapest on the west bank of the Danube. This was a collection point for all the Jews who were to march to Austria.13 She never spoke about what happened in her entire life, but others did. Here is an excerpt from a letter written by another Jewish woman, Mrs. Szenes, who was also forced to march:

As the night fell, it started raining. We continued to march through the mud and the water…and finally we arrived at the brickyard in Óbuda. We were driven to the corridor around the burner, which was so crowded that you could barely stand. The walls of the burner kept us warm so at least the cold did not torture us all night long. It was impossible to sleep, and at dawn, everyone was driven out into the courtyard. We were divided into groups of one hundred, four people in each row. The endless column of human beings started marching towards Austria. Civilian guards were ordered to accompany us, who made no secret out of their unhappiness at having to walk ten or twelve miles a day. They kept an eye on people so that none should escape.

These marches illustrate one of the most inhumane, and frankly absurd, policies of the German authorities. Presumably, they needed the labor to build defensive lines near the border of Austria. However, they didn’t provide the transportation, food, or shelter to protect those assigned to do the work. Thousands of people died along the road to Austria, and those who survived were all too weak to do any useful work once they arrived at their destination.

Back in Budapest, I knew nothing about my mother’s perils. The most annoying part of moving again was that I had to once again carry my basket with the meat grinder. Fortunately, our next stop was a Swedish protected house on Pozsonyi Road just a few blocks away.

It turned out that our new home was also fraught with risks. Arrow Cross men came, and having broken all the understanding established between the neutral countries and the Hungarian government, they herded everybody into the General Ghetto unless they were bribed with money or jewelry. They didn’t care if one had a legitimate or a fake Schutz-Pass—they took everyone. Obviously, we didn’t have enough money, and only a few days after we settled in, we were all marched into the General Ghetto. I was again in charge of carrying the meat grinder back near my grandparents’ house, where we started from a few weeks earlier. This move must have happened in November 1944, before the ghetto was closed on December 10. The borders comprised the core of the old Jewish neighborhoods.

The following streets formed the borders: Dohány Street, Károly Boulevard, Király Street (where my grandparents lived), and Nagyatádi Szabó Street, now named Kertész Street. One of the most memorable events was our entry into the walled ghetto. Families, mostly consisting of older people and children, were lined up next to the wooden fence, and every able-bodied person was carrying something. For a majority of the time we just stood there and then proceeded to walk a few yards. This was fine for me because I could rest my heavy basket on the ground. We approached the ghetto from the west side, where the Great Synagogue is, on Dohány Street.

Finally, as we got close enough, a small gate appeared in the middle of a very high wooden fence stretching between two walls. Men with guns surrounded the gate and people were let through the narrow opening one at a time. To the right of the gate were high piles of objects heaped on the ground. As I got closer, I realized that these piles were silver dishes and utensils, jewelry, watches, rings, and other valuables that people had to discard before entering the ghetto. The uniformed men with guns, the loud noise of shouting and crying, and the sight of all the treasures piled up on the sidewalk were so strange yet entrancing that I don’t even remember walking through the gate.

Moving into the ghetto was a shock to us all. All I remember is that we ended up uncomfortably crowded into one room. There must have been two or three other families already living in the apartment. We were so crowded that Miklós had no room on the floor and he slept on top of a dresser, the only piece of furniture left in the room. The place was dreadfully bug infested, and we all knew that our future prospects were very dim in this place.

Fortunately, Laci Spitzer found out what happened when he came to visit us at our old address and took immediate steps to rescue us. Two days after we were shepherded into the ghetto, Laci showed up fully dressed in his Arrow Cross uniform, followed by a horse and wagon pulled by a man he hired to move us. All our belongings were put into the wagon, along with Laci’s parents, and we left the ghetto and headed to our new destination. The good news, in addition to leaving the ghetto, was that I didn’t have to carry the meat grinder.

In November, it was still safer to be outside the ghetto in a protected house than to be inside. First, obtaining food was easier. Jews could leave the protected houses for a few hours every day to get food. Second, even though the ghetto was completely walled in, soldiers, who guarded its gates, often allowed Arrow Cross units to enter to commit atrocities inside. However, we soon learned that being outside the ghetto had its own perils. There were no physical barriers to keep the increasingly aggressive Arrow Cross thugs from invading the protected houses and dragging the Jews away for summary execution and then dumping them into the Danube.

The food situation had become critical for everybody in Budapest by now. Access to traditional transportation routes into and out of the city was blocked or significantly hampered by the war conditions. Most staples could only be bought on the black market at inflated prices. It was even more challenging for Jews because many shopkeepers refused to sell food to them.

Once again, under Laci Spitzer’s protection, we moved back into the International Ghetto and ended up in another Swedish protected house on 3 Kárpát Street, not too far from the places we stayed before. We were lucky and actually found some food and watches stashed away in a drawer that had been left there by the Jews who were taken away and herded into the ghetto as we were just a few days earlier.

Finding food continued to be the most difficult challenge for us. Whenever Laci came by, he always brought some food for us, but it was never enough. Laci’s parents were too old, my grandparents still didn’t have any papers, and my aunts had to care for the children. The risky job of finding or stealing food fell onto Miklós’s fourteen-year-old shoulders. To quote him, “I was not a child anymore, but I was not quite a grown-up yet.”

Why we didn’t stay at 3 Kárpát Street for more than a few days is still unknown to me. As the end of the war was getting closer, the daily risk of being exposed to the Arrow Cross thugs was obviously increasing. For whatever reason, we were on the road again and subsequently moved back to an apartment on Pozsonyi Road, where we had first stayed.

8. Arrow Cross armband.

There were dozens of other people also crammed into the apartment, and there was barely enough space for people to sleep on the floor. It was in this house that one day Miklós found an Arrow Cross armband on the staircase in our building. He picked it up, making sure nobody saw him, and pocketed it, not really knowing what he might do with it one day. It soon turned out that the armband would be a lifesaver for all of us.

We were living on Pozsonyi Street when Cousin Miklós witnessed a scene that terribly upset him. It was still difficult for him to tell me at the age of seventy-three.

One day as he went about scavenging for food, he saw about a hundred Jews being marched on the street. Guarding them were three or four teenagers with guns and the Arrow Cross armband on their arms. Miklós recalled:

They were like sheep going to the slaughterhouse. Why did a hundred people allow a few teenagers to treat them like sheep? If they attacked their guards, and even if only ten Jews would have escaped and survived, it would have been better than submitting so willingly to a few teenage thugs. To this very day I feel ashamed when I recall this scene.

Miklós was visibly shaken in recalling the incident that took place almost exactly sixty years earlier. As I listened to him, I could feel my throat tighten and my anger rising to the surface. Who was I angry at? The Arrow Cross thugs? At the Jews who allowed themselves to be treated like “sheep”? Or at all those countless people, the Hungarians, the Germans, and all the people around the world who by ignorance, indifference, prejudice, or active collaboration allowed such a scene to take place in Budapest?

I really felt my cousin’s pain as I looked in his tearful blue eyes, searching for an answer to an unanswerable dilemma. By the time Miklós was sixteen, he was fighting another war in Palestine, and I am sure the experiences in Budapest had built up a great deal of resolve in him.

Miklós had gumption, even at the early age of fourteen. As mentioned previously, it was his job to go out of our building day and night, usually without his yellow star, and scavenge and barter for food for the family. Unfortunately, by November 1944, many of the shops were bombed and destroyed, and many of those that were still open for business refused to sell food to Jews.

Miklós would go into a bombed-out building or store and look for anything that had value—a piece of jewelry, a watch, silverware, or a pack of cigarettes—and then barter that for food for the family. As he was returning one day, he saw that all the Jews of our house, including our family, were herded together in courtyard. Here is how Miklós described the scene:

There were a couple of sniveling brats and an old man in Arrow Cross uniforms selecting people from the crowd to take to the Danube. The kids were not much older than I was. The guns on their shoulders touched the ground. Everyone was just standing there scared to death and tolerating it. Suddenly, I remembered that I had an Arrow Cross band in my pocket. I put it on and walked up to the old man and said, “These are my Jews, I will take them.” The old man looked at me, saw my armband, and said, “All right, but be careful that they don’t cheat you.”

The “cheating” was in reference to the allowing of Jews to bribe their way out of certain death by giving the thugs money, jewelry, or other valuables.

Once more, we were on the move. This time we moved into one of the protected houses surrounding Szent István Park. By now, I was barely able to walk, much less carry anything as heavy as the meat grinder. I don’t remember being hungry anymore or even thinking about my mother. Perhaps I had reached the stage of malnutrition when a certain calmness and indifference take over.

From time to time, we heard bombs falling around us. I didn’t know it then, but Miklós told me that the Germans had placed eight guns along the bank of the Danube, right next to the park. One morning the guns were gone, but several Russian airplanes showed up and started bombing the riverbank where they had been. So much for timing!

While we were living at Szent István Park, my grandparents seriously questioned my cousin’s sanity. Following one of his missions to secure some bread, Miklós came home exhilarated and claimed that he saw two of our cousins. He witnessed a squadron of labor camp inmates being marched toward the Big Ghetto in the middle of the street guarded by Arrow Cross men. Marching side by side in the front row were Pisti and Gyuri, the two teenage sons of my mother’s older sister Aunt Bözske,14 and each was carrying a loaf of bread.

Upon hearing of this sighting of family members together in broad daylight with bread under their arms, my grandmother declared, “There is something wrong with this child. He must have been affected by a bomb blast and now he is hallucinating. It is not possible that what he describes is true.” Despite his protestations, Miklós was summarily ignored. However, Miklós proved her wrong after we moved back into the ghetto for the second time.

The situation in Budapest was becoming more and more critical. The Red Army was moving closer and closer to the outskirts of the city. The Germans were withdrawing but didn’t surrender Budapest without a fight.

Knowing that their glorious time of terrorizing defenseless Jews was coming to an end, the Arrow Cross thugs were even more brazen in their attacks. They captured Jews during the hours they were allowed on the streets or dragged them out of their protected houses, taking them to the Danube, murdering them, and dumping their bodies into the river.

One day we were told to pack up and be prepared to move again. All the Jews in the houses on Szent István Park were gathered on the street, and we were marched off, Miklós carrying me on his back. Laci Spitzer was nearby and kept an eye on us, but we still didn’t know where we were going. Were we heading to the embankment of the Danube or into the Big Ghetto?

As we turned left on the main road, we knew we were heading toward the ghetto. Suddenly, we heard the roar of airplanes flying over, and we soon saw and heard the bombs exploding near us. Aunt Klári panicked, decided to bolt from the row, pushing her son Iván in the wheelchair, and ducked inside a house along the road. Normally, this would have been suicide due to the Arrow Cross shooting all deserters on the spot. This time, Aunt Klári got lucky. Because of the chaos of the bombing, and before anything tragic could happen, my grandfather swiftly dragged her back into the line.

We moved back into the ghetto around the end of December 1944, and this was the last place we stayed until the Red Army liberated the ghetto in January 1945. This second and last entry into the ghetto was through the same gate we used the first time. Unlike our first entry into the ghetto, I cannot recall going through the same gate. Laci came into the ghetto, wearing his black Arrow Cross uniform, armband, and shiny boots, and managed to put us in a single room in an apartment building at 34 Kazinczy Street, right across from a small synagogue.

Somewhere along the way, moving from one place to the next, my new white long pants that I was so proud of and had barely an opportunity to wear had disappeared. I was inconsolable over their loss, no matter how much the grown-ups tried to convince me that I would get another pair.

As soon as we moved into the ghetto, Miklós took off to look for the cousins he had seen a couple of days earlier. He was determined to prove to our grandmother that he wasn’t hallucinating. Sure enough, after going from house to house, he found them all and was hoping they still had some of the bread they were carrying on the street. This is when he learned that the bread they had carried was allotted for the whole squadron and was long gone.

Miklós brought our two cousins, Pisti and Gyuri, to visit us in our tiny room, where there was a bittersweet rejoicing at having reunited. Everybody was indifferent by now. Having seen and suffered so much, we all sensed that the outlook was grim. It was difficult to celebrate a reunion when everyone was starving and when so many of our family were missing and presumed already dead.

The food situation in the ghetto was desperate because there wasn’t any. A potato skin found on the floor was a treasure. Kitchens were set up at several places within the ghetto that were supposed to dispense about seventy thousand portions a day. Unfortunately, the raw materials the government was expected to provide for the ghetto were rarely delivered. It fell to the International Red Cross to provide the staples, which often fell short. After all, we were on the front line of a war zone.

The food shortage created a despondent situation for everyone in the ghetto, and only those with money or outside connections could secure additional food for their families. Documents found among the papers of the ghetto administrator, Captain Miksa Domonkos of the Hungarian Army, indicate the caloric content of the daily portions distributed:

| Child’s portion: | 931 calories |

| General portion: | 781 calories |

| Sick portion: | 1,355 calories |

According to the “Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005” released on January 12, 2005, by the US government, daily calorie intake recommended for “moderately active” people between the ages of thirty-one and fifty was 2,000 calories for women and 2,400 to 2,600 calories for men. Therefore, nobody could survive on the portions in the ghetto for long.

These documents also showed the weekly menu in December 1944:

| Monday: | bean soup with pasta (14 ounces)15 |

| Tuesday: | dish of cabbage (10.5 ounces) |

| Wednesday: | potato soup (14 ounces) |

| Thursday: | dish of dried peas (10.5 ounces) |

| Friday: | caraway seed soup (14 ounces) |

| Saturday: | sholet16 (10.5 ounces) |

| Sunday: | vegetable soup and pasta (14 ounces) |

At that time, the only physical discomfort I felt was the cold. Heating materials weren’t available as winter arrived in the city; most modern city apartment houses were heated with built-in stoves that used wood and coal. The mean temperatures in Budapest in November and December are 41oF and 34oF, respectively, with the temperature often dropping below freezing at night. The windows were all broken, and the walls of our room provided the only protection against the elements.

I kept getting weaker and weaker until I was no longer interested in getting up in the morning at all. I didn’t miss much fun since we were crowded into a small room, sleeping on blankets on the floor and huddling together to keep ourselves warm, just waiting for something to happen.

We were on the second floor of the building, and to my right there were two windows facing the synagogue across the street. There was not a single piece of furniture save for a wall-mounted grandfather clock that hung over my grandparents’ heads across the room. All other furniture that once made this room part of a family home had already been sold or used up as firewood. The image of the grandfather clock with its motionless brass arm is stuck in my mind like an old photograph. I was frightened that it could come crashing down on my grandparents’ heads at any time. Miklós stated that the building belonged to the clock makers’ union, explaining the presence of the wall clock.

I went to Hungary in 2007 to attend a family wedding, and I decided to find 34 Kazinczy Street. Amazingly, this was the only house on the street whose façade has not been renovated. It stood exactly like it was in 1945 with its bullet holes and scars from bomb shrapnel, a testament to the events of more than sixty years ago. The only difference is that all the windows had been replaced. It is now a surreal picture of wartime Budapest since almost all the surrounding buildings on both sides of the street have been rebuilt or renovated. The small synagogue across the house was no longer in use. I thought maybe this house stayed this way so I could take a picture and show it to my grandchildren.

9. 34 Kazinczy Street in 2007, where we survived the final weeks of the Holocaust.

Raids on Budapest continued, but we didn’t seek shelter in the basement as my mother and I used to do in our home. There was a cellar under the building; however, the grown-ups decided that it was unnecessary to trek up and down every time the air raid siren went off. The bombs fell on Budapest day and night, some of which landed in the ghetto. Strangely, I didn’t fear the bombs, but as I later discovered—twenty years after these events—I didn’t totally escape the psychological impact.

In July of 1964, when I was already married and our son was less than a year old, I had just started working for General Electric in Philadelphia. It was my first job after graduating from college, and we had recently rented an upstairs furnished apartment in Broomall, a suburb of the city.

One night I awoke suddenly to the sound of sirens. I immediately broke out in a cold sweat, jumped out of bed, and ran to the balcony. I stared at the sky, seeking the air-raid searchlights that were used in Budapest in 1944, and listened for the familiar sound of bombers flying over. However, it took me a few minutes, standing there stark naked with sweat pouring down, to realize that I was in Broomall, Pennsylvania, and not back in Budapest. It was only the next day that I learned the siren was the call signal for the volunteer firefighters to rush to their station. Fortunately, this was the only such incident.

Back in Budapest in December 1944, I must have been emotionally numb after everything that had happened during the previous months. Bombings didn’t bother me, and I was getting used to being hungry and cold all the time. My Cousin Tomi was in even worse shape, though he was three years older. A month or so earlier, a bomb exploded nearby at Légrádi Károly Street, the first place we moved to after leaving my grandparents’ place. Consequently, Tomi had become almost catatonic. He completely shut down and to this day has no recollection of anything that happened then. However, the month of December 1944 proved to be one of fateful and historic events:

December 15: The German government fled the city, and the activities of the Red Cross were banned. Armed bands of Arrow Cross soldiers began a string of systematic murders of Jews. On the same day, rail tracks were laid down up to the wall of the ghetto. It seemed that this was in preparation for deportation of the ghetto inhabitants to Auschwitz.

December 20: Several bombs hit the ghetto during the night, seriously damaging five houses where close to six hundred people lived, many of whom died.

December 22: Eichmann personally visited the ghetto and ordered the Jewish Council17 members to meet him the next morning at nine o’clock. His plan was to personally supervise the execution of the Jewish Council, followed by the massacre of the entire Jewish population of the ghetto.

December 23: Eichmann decided to leave Budapest at dawn as the news spread of the Soviet Army’s push to the outskirts of Budapest, thus averting the massacre of seventy thousand Jews.

December 23: Representatives of the neutral countries18 who had not yet left the city met and delivered a memorandum to the royal government of Hungary, protesting against transporting Jewish children found hiding elsewhere into the ghetto.

December 24: The Soviet Army surrounded the city, and the siege of Budapest began.

December 31: Corpses of the dead could no longer be taken out of the ghetto for burial. Many were lined up in the small courtyard of the synagogue on Dohány Street, today called the Hero’s Cemetery. To this day, two thousand victims rest there.

Life in the ghetto became quite perilous in December 1944. In addition to starvation, the cold, and bombs, there were bands of Arrow Cross soldiers determined to take as many Jews as they could out of the ghetto and murder them. An excerpt from the diary of a survivor, Miksa Fenyő, hiding not far from the ghetto on December 23, 1944, illustrates the dangers we faced every day:

There seems to be no end to the robbery and murder. No day goes by without a few dozen Jews dragged out of the ghetto on the slightest pretext, or on no pretext at all. At night they are shot to death along the banks of the Danube, to save the trouble of a burial.

A couple of stories my cousin recalled illustrate how pure luck played a crucial role in survival. The fear of Arrow Cross men dragging Jews away from the ghetto was so great that a decision was made to post a “guard” at the gate of our building. All grown-ups had to stand guard for two hours all day and night to alert us in case the Arrow Cross men were near. I’m not sure what we would have done if an alarm sounded, but being on guard kept the grown-ups proactive.

One evening my Aunt Piri was on guard when a man in our building volunteered to take her place and told her to go back upstairs and take care of her family. “I am a single man, but you have a family to take care of. I will take your watch,” he told her, and she came upstairs. Ten minutes later a bomb fell into the yard near the gate and instantly killed this Good Samaritan instead of my Aunt Piri.

There was another incident that involved Miklós. It was his responsibility to go to the ghetto kitchen and return with the daily soup portions for the whole family. He collected the soup in a big pot and was on his way back to our building when he heard the Soviet planes flying over with their guns blazing. He took cover on the side of a house until the planes disappeared. Upon hearing a sharp noise, he looked down into the pot and realized that the soup was gone. A bullet hole had penetrated the pot, causing all the soup to leak out.

By now, the Red Army was fighting the Germans and the Arrow Cross men city block by city block. The Soviets weakened the resistance by attacking Germans behind the front line via airplane. As we were surrounded by German troops, it was not easy to see the wooden fence boundaries of the ghetto from an airplane flying at 150 mph with guns blazing. According to Miklós, our situation looked very bleak by January 1945, and apathy and hopelessness were spreading.

Desperation for food had reached a new high when we somehow got hold of some starch. We were not sure what we could do with it until Aunt Piri suggested that we try to mix it with the very fine lubricant oil that the clock makers who used to live in the apartment used. A few books were found in the building, and the potbelly stove was fired up. Aunt Piri mixed the oil with the starch, and the fried mixture soon had the appearance of traditional latkes, a traditional Jewish side dish for Chanukah. We all ate it and thankfully nobody got sick, but I doubt that this new recipe for latkes will ever find its way into a Jewish cookbook.

On January 15, 1945, after the Soviet Army had already captured the outskirts of the city, remaining SS units and armed Arrow Cross men planned to launch an attack on the ghetto to slaughter everyone per Eichmann’s original plan. Thankfully, Raoul Wallenberg discovered the plan on January 12 and threatened the SS commander, General Schmidhuber, with severe consequences if it was carried out. The massacre of seventy thousand Jews was averted, and thus we survived.

Liberation

My last memory of the ghetto is the day of liberation. I had no idea when exactly the ghetto was liberated until I did the research for this story. Based on my impression that we lived in the ghetto for a very long time, I always thought that it was in the spring of 1945. I felt surprised, as well as dismayed, to discover that the day the Soviet Army liberated the Budapest ghetto was on January 18. Therefore, we lived in the Big Ghetto just a few weeks, not several months as I had thought. The corollary to the saying that time flies when you are having fun should be time stands still when you are miserable.

According to my Cousin Miklós, the fighting erupted literally under our windows one morning. Then suddenly there was quiet. While I don’t recall the fighting, I do remember one of my aunts taking me to the window to look. I saw uniformed men marching off in the distance, pulling what appeared to be guns on two wheels, and then disappearing at the end of the street. All these years I always thought what I saw then were German soldiers. However, according to my cousin, it is possible that these were Arrow Cross men fighting to the very end. For them, liberation meant the end of their regime and possible death. They had nothing to lose by fighting for every inch of territory.

Gunfire continued to be heard in the distance, but it was silent in front of our building. In what seemed like minutes, soldiers of the Soviet Army appeared at the opposite end of the street. They came into the ghetto through the eastern gate, moving west block by block. I then heard yelling and screaming as the Russians drew closer to our house. The Russian word for “bread,” chleba, was being shouted from the windows and by people rushing out of the houses toward the soldiers.

My grandfather, having been a prisoner of war in Russia for five years during World War I, spoke some Russian, and he was out of our building in a hurry to get some bread for us. By this time even Miklós was so weak that he could barely drag himself to the window to witness the dramatic events.

Finally, on January 18, 1945, we went from being exposed to imminent death to being free within one day. Any memories of celebration or laughter have escaped me. It is possible that everybody was still in shock and ridden with anxiety about what they had gone through and about the fate of the rest of their families.

Laci Spitzer, our guardian angel, showed up in the ghetto the day we were freed and took his parents with him. I never saw him again until we met in 1957 in Montréal, Canada. Like me, Laci escaped from communist Hungary following the Uprising in October 1956. We met many times in Montréal, and I even remember visiting him and his wife, Erzsi, in their lovely apartment in downtown Montréal. He never mentioned anything about what happened to us back in 1944 and 1945, and I knew nothing about the role he played in my family’s survival until I visited my cousins in Sydney, Australia, in December 2004.

The very next day my grandfather and Miklós went to scout out the situation at 106 Király Street to make sure that it was safe and ready for our family to move back in. A peasant family from the country who had occupied our home was asked to leave, and by nightfall the next day we were back home. Fortunately, we didn’t have to walk too far because my grandparents’ home was just a few blocks from the ghetto. Who carried me back remains a mystery, as does what happened to the meat grinder.

A couple of days after the liberation of Budapest, Raoul Wallenberg was captured by the Red Army, and for decades the Soviet Union refused to provide information about his whereabouts or whether he was dead or alive.

10. Members of the International Red Cross examining a pile of dead bodies in the Big Ghetto following liberation in January 1945.