Читать книгу What it Means to be Human - Robert Rowland Smith - Страница 25

Haunting

ОглавлениеThat wasn’t the main reason why I stayed up in Oxford that first summer. Though I too struggled with the comedown in our family fortunes. The loss of social status became all the more acute on going up to Oxford. I could see up close the real-life toffs at Christ Church and Worcester and Magdalen. These were the gilded youth who hailed from old money, had houses in the country, and all knew each other – my peers included David Cameron and Boris Johnson. Before going up, I had assumed that Oxford would be about the scaling of intellectual summits. I soon realised that social altitude mattered more. Being middle class and intellectual was somewhat suspect. Better to be a bit less bright and a bit more posh. I’d been a keen actor at school and a member of the National Youth Theatre, and Oxford would be a chance for me to take some interesting new roles … but the roles were always taken by these chums with skiing holiday tans, liberal allowances and bow ties that needed to be tied.

A short note on cars

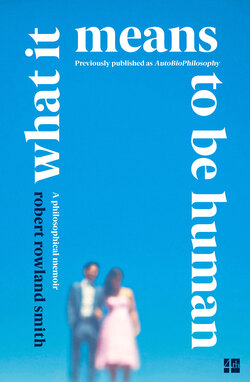

The Chrysler in the photo was one of several owned by my grandfather with an ‘Oak’ licence plate. The registration number refers to ‘Ye Olde Oak’, the brand name of the tinned ham produced by Rowland Smith & Son Ltd. In the mid 1970s, this vehicle was sold to none other than David Bowie, who was then in his ‘plastic soul’ phase, and wanted an American car to drive in England. A Chrysler features in his 1975 song ‘Young Americans’. Perhaps it was this one. When my father had to give up driving, it represented another break with the Oak dynasty, and a loss of male energy. My own dreams often feature cars. The kind of car I’m driving and the journey I’m on seem to indicate my state of mind at the time.

Admittedly, I had been to a private school myself – the same Dulwich College that my mother aspired to on her son’s behalf. But Dulwich was a school for new-money boys from Beckenham or Bromley or, like me, Croydon. By contrast, those bright young things had carved out an elite within the elite, an inner sanctum of privilege cordoned off with a red rope and guarded by a PR team with a list of names from which mine was absent. I wasn’t sure if I hated them or wished I was one of them. Probably both.

Ultimately, staying away that summer was a means of avoiding living under the same roof as my father in his castrated state. A state like that of King Lear turfed out of his castle, confined to the outbuildings with the animals. It would have meant seeing his reality first hand. I use the word ‘castrated’ deliberately. Though the MS would sure enough disable his sexual functioning along with everything else, it was more that the symbolic male energy that should have flowed from father to son, from him to me, had been interrupted. The oil pipeline, the artery of resources, had been blown up by terrorists. Just as I was making my transition from adolescence to the big wide world, and needing male fuel to boost me on, the engine cut out.

More usually the reverse applies: paternal potency induces filial feebleness. There are billionaire fathers with wastrel sons, and celebrity fathers whose male progeny live in their shadow. In those cases, it is an excess rather than an insufficiency of fatherly strength that causes the son to weaken. For me, it was the other way round. And it was as much about timing as anything else. At the point of leaving home I needed a full tank. I had expected my father to fill it up as a parting gift. I got only a few miles down the road before the engine sputtered and died. Why had my father stopped earning money to support me? Why couldn’t he have an influential job for me to boast about? Why did he have to crumple into his own despair rather than steer me with gubernatorial ease towards a sure destiny? I felt angry with him, disappointed, cheated.

To tell the awkward truth, I felt it would have been better if he had died. To me he was like a bloodied bull staggering around the bullring, dazed and confused, the picos sticking out from his neck to make a grotesque ruff. A part of me was praying for the matador to put him out of his misery. At least then I would have the opportunity to mourn. In the terms of Sigmund Freud, I would have been able to ‘incorporate’ him properly. Instead, he was cast into a limbo between life and death. That made it impossible for me as his son to abstract the remaining heat from his corpse, like an electricity thief, and plug it into my own circuit of veins. For Freud, this is one of the chief causes of depression, or what he calls ‘melancholia’. Instead of being able to grieve fully for somebody by incorporating them into our memories, we are impeded. They remain only half taken in, and that induces a terrible sadness.

But Freud is talking about people who actually die. He is describing a failure of mourning on the part of those who survive them. My dad did not actually die. Rather, he lived a half life, as if he’d been exposed to radiation. He would stir only to do sums on blotting paper, working out how to eke out his savings, now that no more income was coming in. This half life, half death on his part was the cause of my half mourning. I’ve effectively remained in this state of half mourning ever since that rupturing of the masculine tract. I think it lies behind the dejection I experienced at Oxford. Freud refers to primitive societies in which the dead king is literally eaten, ingested, as a way of tapping his energy. Not eating leaves you weak. We grow in strength when we consume dead meat. We need the body of the past to sustain us for the future.fn1

The implication is that when you fully incorporate the dead, you won’t be haunted by them. They will be satisfactorily swallowed, and you can get on with your business, just as if you’d had a restorative meal. Haunting is less a spectral visitation, in other words, than a failure of mourning. It’s not that the dead return, but that the living haven’t digested them properly. The living thus keep burping up the dead like a gas which takes human shape, its hologram shimmering before their eyes. And because, with the onset of his two irreversible conditions, MS and unemployment, my father entered a zone that was also neither dead nor alive, it turned him into a kind of ghost that haunted me. It was his ghostly half-presence that spooked me, and I couldn’t face living in the little house with it for a whole summer.

But nor could I fight with him. Young adult sons need not only to draw from the male strength of the father, but also to do battle with it. There has to be some alpha wrangle that lets the son believe he has thrown the father over. It’s an Oedipal crisis that tightens the relationship between father and son like a screw until the wood splits, and the parts can become individual again. With a damaged father, one mother, two sisters and no brother, I lacked a male adversary to define myself against. My father had become a ghostly gas (the two words are related), and I could punch right through it.

The word ‘Oedipal’, of course, refers to the Oedipus complex as elaborated by Freud. The original version by Sophocles sees Oedipus unwittingly kill his father and marry his mother. Freud recasts the Greek original in psychological terms in order to reveal a general tendency among boys to attack their fathers while idealising their mothers. He says that it is an important phase for a boy to go through. As in, go through and come out the other side. In my attempt here at a Freudian self-analysis, I’m saying that I never quite went through it, or that I might still be stuck in an unresolved version thereof. I couldn’t attack my father because he couldn’t fight back.

And if I couldn’t elbow my way beyond that aggressive phase with my father, does it imply that I remained in a state whereby I idealised my mother in Oedipal fashion? As I pointed out in the Foreword, this book contains disproportionately more material about my father than about my mother. I would answer that writing less about my mother does indeed contain a residual motive to idealise, but in the following sense. Just as my teenage self was squaring up to fight him, I saw that my father was already on the canvas, knocked out by life. With one parent down, and still down to this day – as I write Colin lies in his hospital bed ten miles away – how could I possibly risk damaging the other parent too? Would analysing my mother in the way that I have analysed my father undermine the consolation that I derive from having at least one parent not sitting on death row? Even if any illusions that I hold about my mother serve merely to compensate for the disillusion with my father, that is fine by me. My silence about my mother keeps those illusions about her alive. Those illusions, if they exist, serve a purpose.

Whether or not my self-analysis is valid, it was because of that father–son dynamic that I didn’t go home that first Oxford summer. The following year, 1986, I took up the summer job at the call centre and met Simone. Having dropped out of college, I started wondering what I would do with my life.