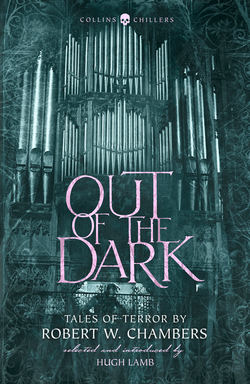

Читать книгу Out of the Dark: Tales of Terror by Robert W. Chambers - Robert W. Chambers - Страница 24

IV

ОглавлениеShe was standing still when I approached the pool. The forest around us was so silent that when I spoke the sound of my own voice startled me.

‘No,’ she said – and her voice was smooth as flowing water, ‘I have not lost my way. Will he come to me, your beautiful dog?’

Before I could speak, Voyou crept to her and laid his silky head against her knees.

‘But surely,’ said I, ‘you did not come here alone.’

‘Alone? I did come alone.’

‘But the nearest settlement is in Cardinal, probably nineteen miles from where we are standing.’

‘I do not know Cardinal,’ she said.

‘Ste. Croix in Canada is forty miles at least – how did you come into the Cardinal Woods?’ I asked amazed.

‘Into the woods?’ she repeated a little impatiently.

‘Yes.’

She did not answer at first but stood caressing Voyou with gentle phrase and gesture.

‘Your beautiful dog I am fond of, but I am not fond of being questioned,’ she said quietly. ‘My name is Ysonde and I came to the fountain here to see your dog.’

I was properly quenched. After a moment or two I did say that in another hour it would be growing dusky, but she neither replied nor looked at me.

‘This,’ I ventured, ‘is a beautiful pool – you call it a fountain – a delicious fountain: I have never before seen it. It is hard to imagine that nature did all this.’

‘Is it?’ she said.

‘Don’t you think so?’ I asked.

‘I haven’t thought; I wish when you go you would leave me your dog.’

‘My – my dog?’

‘If you don’t mind,’ she said sweetly, and looked at me for the first time in the face.

For an instant our glances met, then she grew grave, and I saw that her eyes were fixed on my forehead. Suddenly she rose and drew nearer, looking intently at my forehead. There was a faint mark there, a tiny crescent, just over my eyebrow. It was a birthmark.

‘Is that a scar?’ she demanded drawing nearer.

‘That crescent-shaped mark? No.’

‘No? Are you sure?’ she insisted.

‘Perfectly,’ I replied, astonished.

‘A—a birthmark?’

‘Yes – may I ask why?’

As she drew away from me, I saw that the color had fled from her cheeks. For a second she clasped both hands over her eyes as if to shut out my face, then slowly dropping her hands, she sat down on a long square block of stone which half encircled the basin, and on which to my amazement I saw carving. Voyou went to her again and laid his head in her lap.

‘What is your name?’ she asked at length.

‘Roy Cardenhe.’

‘Mine is Ysonde. I carved these dragonflies on the stone, these fishes and shells and butterflies you see.’

‘You! They are wonderfully delicate – but those are not American dragonflies—’

‘No – they are more beautiful. See, I have my hammer and chisel with me.’

She drew from a queer pouch at her side a small hammer and chisel and held them toward me.

‘You are very talented,’ I said, ‘where did you study?’

‘I? I never studied – I knew how. I saw things and cut them out of stone. Do you like them? Some time I will show you other things that I have done. If I had a great lump of bronze I could make your dog, beautiful as he is.’

Her hammer fell into the fountain and I leaned over and plunged my arm into the water to find it.

‘It is there, shining on the sand,’ she said, leaning over the pool with me.

‘Where,’ said I, looking at our reflected faces in the water. For it was only in the water that I had dared, as yet, to look her long in the face.

The pool mirrored the exquisite oval of her head, the heavy hair, the eyes. I heard the silken rustle of her girdle, I caught the flash of a white arm, and the hammer was drawn up dripping with spray.

The troubled surface of the pool grew calm and again I saw her eyes reflected.

‘Listen,’ she said in a low voice, ‘do you think you will come again to my fountain?’

‘I will come,’ I said. My voice was dull; the noise of water filled my ears.

Then a swift shadow sped across the pool; I rubbed my eyes. Where her reflected face had bent beside mine there was nothing mirrored but the rosy evening sky with one pale star glimmering. I drew myself up and turned. She was gone. I saw the faint star twinkling above me in the afterglow, I saw the tall trees motionless in the still evening air, I saw my dog slumbering at my feet.

The sweet scent in the air had faded, leaving in my nostrils the heavy odor of fern and forest mould. A blind fear seized me, and I caught up my gun and sprang into the darkening woods. The dog followed me, crashing through the undergrowth at my side. Duller and duller grew the light, but I strode on, the sweat pouring from my face and hair, my mind a chaos. How I reached the spinney I can hardly tell. As I turned up the path I caught a glimpse of a human face peering at me from the darkening thicket – a horrible human face, yellow and drawn with high-boned cheeks and narrow eyes.

Involuntarily I halted; the dog at my heels snarled. Then I sprang straight at it, floundering blindly through the thicket, but the night had fallen swiftly and I found myself panting and struggling in a maze of twisted shrubbery and twining vines, unable to see the very undergrowth that ensnared me.

It was a pale face, and a scratched one that I carried to a late dinner that night. Howlett served me, dumb reproach in his eyes, for the soup had been standing and the grouse was juiceless.

David brought the dogs in after they had had their supper, and I drew my chair before the blaze and set my ale on a table beside me. The dogs curled up at my feet, blinking gravely at the sparks that snapped and flew in eddying showers from the heavy birch logs.

‘David,’ said I, ‘did you say you saw a Chinaman today?’

‘I did sir.’

‘What do you think about it now?’

‘I may have been mistaken sir—’

‘But you think not. What sort of whiskey did you put in my flask today?’

‘The usual sir.’

‘Is there much gone?’

‘About three swallows sir, as usual.’

‘You don’t suppose there could have been any mistake about that whiskey – no medicine could have gotten into it for instance.’

David smiled and said, ‘No sir.’

‘Well,’ said I, ‘I have had an extraordinary dream.’

When I said ‘dream’, I felt comforted and reassured. I had scarcely dared to say it before, even to myself.

‘An extraordinary dream,’ I repeated; ‘I fell asleep in the woods about five o’clock, in that pretty glade where the fountain – I mean the pool is. You know the place?’

‘I do not sir.’

I described it minutely, twice, but David shook his head.

‘Carved stone did you say sir? I never chanced on it. You don’t mean the New Spring—’

‘No, no! This glade is way beyond that. Is it possible that any people inhabit the forest between here and the Canada line?’

‘Nobody short of Ste. Croix; at least I have no knowledge of any.’

‘Of course,’ said I, ‘when I thought I saw a Chinaman, it was imagination. Of course I had been more impressed than I was aware of by your adventure. Of course you saw no Chinaman, David.’

‘Probably not sir,’ replied David dubiously.

I sent him off to bed, saying I should keep the dogs with me all night; and when he was gone, I took a good long draught of ale, ‘just to shame the devil’, as Pierpont said, and lighted a cigar. Then I thought of Barris and Pierpont, and their cold bed, for I knew they would not dare build a fire, and, in spite of the hot chimney corner and the crackling blaze, I shivered in sympathy.

‘I’ll tell Barris and Pierpont the whole story and take them to see the carved stone and the fountain,’ I thought to myself; what a marvelous dream it was – Ysonde – if it was a dream.

Then I went to the mirror and examined the faint white mark above my eyebrow.