Читать книгу Tokyo Junkie - Robert Whiting - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

The late Anthony Bourdain, renowned celebrity chef and globetrotter, in an interview with Maxim in 2017, named Tokyo as his favorite city in the world and said, “If I had to agree to live in one country, or even one city, for the rest of my life, never leaving it, I’d pick Tokyo in a second.” He called his first trip to Tokyo, in general, an “explosive, life-changing event” and even compared it to the first time he ever took acid, in the way it changed every experience that came after it. “Nothing was ever the same for me,” he said, fascinated with the city’s myriad layers and the variety of its flavors, taste, and customs. “I just wanted more of it.”

I understood what he was saying because I had felt the same way when I first came to the city over five decades ago in 1962 as a raw nineteen-year-old GI from small-town America. It was a time when the United States was at the peak of its economic power under iconic new president John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Japan was still struggling to recover from the damage of defeat in World War 2.

Tokyo, at the time, was tearing itself apart and putting itself back together in preparation for the Tokyo Olympics. You could stand in parts of the city and watch as buildings were being torn down on one side of the street and new ones constructed on the other. I had arrived at what someone would later describe as the biggest construction site in the world.

I watched fascinated, astonished, as, before my eyes, the city evolved, in a few short years, from a fetid, disease-ridden third-world backwater into a modern megalopolis in what many believe to be the greatest urban transformation in history. Tokyo then staged what Life magazine called “the Greatest Olympic Games ever.”

I was as naïve as they come. I had grown up in Eureka, a small fishing and logging town on the coast of northern California. Military training in Texas, Intelligence school in Mississippi, and a weekend in New Orleans. That was all I knew of the outside world. My knowledge of Japan was limited to Godzilla movies, dubbed in bad English, I had seen at the Eureka Theater. In fact, the first thing I did on my initial visit to Tokyo was to look for the Diet Building that Godzilla had destroyed in his debut Toho feature.

But I was hypnotized by the energy of the place—the ubiquitous neon signs, the endless nightlife—and so I chose to stay on in Tokyo. I went on to graduate from the Jesuit-founded Sophia University in the city and grew into adulthood there, surviving a self-destructive tailspin into the Dark Heart of its seductions that caused me to pack up and move to New York for three years to recover.

Finally, I settled down to become the author of several successful books over a four-decade span. Along the way I met a lot of fascinating people: newspaper barons, politicians, baseball stars, famous writers, yakuza enforcers, and other denizens of the city’s underworld. I also met my wife, with whom I would spend over forty-five years, dividing my time between Japan and the numerous global capitals where she worked as a United Nations officer.

Tokyo grew right alongside me. It became the richest city in the world, riding the back of the global trade juggernaut Japan built in the aftermath of the ’64 Games. It weathered the real estate collapse of the bubble era, got its choking pollution under control, covered the landscape with a succession of high-rise buildings, and became what many people regard as the cleanest, safest, most modern, most transportation efficient, most fashion conscious, and the politest city anywhere—with arguably the best selection of restaurants on the planet, boasting more than twice as many Michelin three-star restaurants as any other city, including Paris. The aforementioned Bourdain declared the food in the city superior, on “virtually every level and price point.”

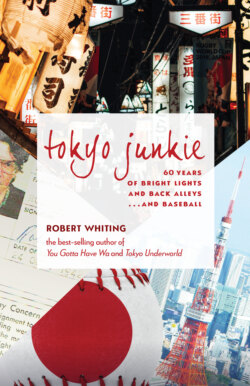

Robert Whiting. Tokyo, 1962.

By 2018, Tokyo had actually passed Paris as the world’s leading tourist destination. Trip Advisor, the largest travel website in existence, asked its users to rank the thirty-seven top cities across the globe in terms of “the most satisfying” to visit. Tokyo was voted #1 in the world, topping several of the sixteen categories listed, including local friendliness, taxi services, cleanliness, and public transportation. I’d lived in or visited extensively many of those places mentioned in the survey and I would have voted the same.

The city may have its flaws: crushing rush-hour crowds, mindless bureaucracy (in the great typhoon of fall 2019 in Tokyo, homeless people were denied entry to a shelter because they could not provide a residence address), and certain gender-equality issues. There are also questions about press freedom, rampant cronyism in politics, and a government that is all too often enmeshed in scandal.

But the good, in my opinion, outweighs the bad.

***

Tokyo is now the largest city on the planet, with thirty-eight million inhabitants in the Greater Metropolitan Area—thirteen million in the city proper. Tokyo has the highest GDP of any city at $1,520 billion, ahead of New York City, Los Angeles, Seoul, London, and Paris. Tokyo also has more Fortune 500 global headquarters than anywhere else and boasts a newly minted, awe-inspiring metropolitan skyline that ranks with that of Manhattan, Sydney, and other great capitals. The city also ranks among the highest around the globe in terms of literacy levels, with a rate of 99 percent for people above the age of fifteen, and life expectancy, with almost a quarter of the population over the age of sixty-five. Special features incorporated by the city fathers to accommodate Tokyo’s aging society include talking traffic lights and ATMs, as well as ubiquitous directional tactile pavers to aid pedestrians with poor eyesight, along with special ramps accompanying steps in train stations and public buildings for the benefit of the less mobile.

In 2013 I watched as Tokyo won the bid to host another Olympics, this one scheduled for 2020, fifty-six years after the first one, if under vastly different and improved circumstances. I looked on with not a little interest as preparations began for an army of robots to help with language translation, directions, and transportation; driverless cabs; 8K TV broadcasts; algae and hydrogen as clean alternative energy sources; demonstrations of Maglev trains running nearly 400 miles per hour; and man-made meteors streaming across the sky from satellites in space for the opening ceremony. You could feel the buzz.

From my office window in Toyosu—built partially on reclaimed land at the northern end of Tokyo Bay and yet another bustling new quarter of commerce and leisure filled with skyscrapers of both the office and residential variety—I had a bird’s-eye view of the Olympic Village for the 2020 Games erected under the shadow of the Rainbow Bridge. In my mind’s eye I could see another Olympic Village from fifty-six years ago. Tokyo and I had come full circle. The perfect time to write a memoir had arrived, and, as chance would have it, that time would be accompanied by a coronavirus pandemic that would keep me in isolation for extended periods, allowing for total dedication to the task at hand. It also necessitated the first postponement in Olympic history.

My story is part Alice in Wonderland, part Bright Lights, Big City, and part Forrest Gump, among other things. It is a coming-of-age tale as well as an account of a decades-long journey into the heart of a city undergoing one of the most remarkable and sustained metamorphoses ever seen. It is also something of a love story, with all the irrational sentimentality that term entails. Tokyo and I have had our differences, our ups and downs—I once left for what I thought was good, so tired of being a gaijin (outsider) that I thought I would die if I stayed any longer—but as our relationship reaches the end and I look back, I must say that all in all it was the right place to spend all these years.

It is not too much to say that I am what I am today because of the city of Tokyo. It was here that I learned the art of living, discovered the importance of perseverance, grew to appreciate the value of harmonious relations as much as individual rights, and came to rethink what it means to be an American as well as a member of the larger human race.