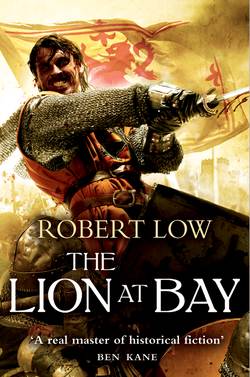

Читать книгу The Complete Kingdom Trilogy: The Lion Wakes, The Lion at Bay, The Lion Rampant - Robert Low - Страница 17

ОглавлениеChapter Six

Edinburgh

Feast of St Giles – August 1297

The church of St Giles was muggy, blazing with candles and the fervour of the faithful. Hot breath drifted unseen into the incense-thick air, so that even the sound of bell and chant seemed muted, as if heard underwater. The wailing desperate of Edinburgh crowded in for their patron’s Mass, so that the lights fluttered, a heartbeat from dying, with their breathy prayers for intercession, for help, for hope. There were even some English from the garrison, though the castle had its own chapel.

The cloaked man slipped in from the market place, slithering between bodies, using an elbow now and then. In the nave, the ceiling so high and arched that it lost itself in the dark, the gasping tallow flickered great shadows on stone that had never seen sunlight since it had been laid and the unlit spaces seemed blacker than ever.

In the shade of them, folk gave lip-service to God and did deals in the dark, sharp-faced as foxes, while others, hot as salted wolves, sought out the whores willing to spread skinny shanks for a little coin and risk their souls by sweating, desperate and silent, in the blackest nooks.

‘O Lord,’ boomed the sonorous, sure voice, echoing in dying bounces, ‘we beseech you to let us find grace through the intercession of your blessed confessor St Giles.’

The incense swirled blue-grey as the robed priests moved, the silvered censers leprous in the heat. The cloaked man saw Bisset ahead.

‘May that what we cannot obtain through our merits be given us through his intercession. Through Christ our Lord. Amen. St Giles, pray for us. Christ be praised.’

‘For ever and ever.’

The murmur, like bees, rolled round the stones. The cloaked man saw Bisset cross himself and start to push through the crowd – not waiting for the pyx and the blessings, then. No matter … the cloaked man moved after him, for it had taken a deal of ferreting to get this close and he did not want to lose him now. All he needed to know from the fat wee man was what he knew and whom he had told.

Bartholomew was no fool. He knew he was being followed, had known it for some time, like an itch on the back of his neck that he could not scratch. Probably, he thought miserably, from the time he had left Hal Sientcler and the others at Linlithgow long days ago.

‘Take care, Master Bisset,’ Hal had said and Bisset had noted the warning even as he dismissed it; what was Bartholomew Bisset, after all, in the great scheme of things?

He would travel to his sister’s house in Edinburgh, then to Berwick, where he heard the Justiciar had taken up residence. He was sure Ormsby, smoothing the feathers that had been so ruffled at Scone, would welcome back a man of his talents. He was sure, also, that someone had tallied this up and then considered what Bartholomew Bisset might tell Ormsby, though he found it hard to believe Sir Hal of Herdmanston had a hand in it – else why let him go in the first place?

Yet here he was, pushing into the crowded faithful of St Giles like a running fox in woodland, which was why he had turned into Edinburgh’s High Street and headed for the Kirk, seeking out the thickening crowds to hide in. He did not know who his pursuer was, but the thought that there was one at all filled him with dread and the sickening knowledge that he was part of some plot where professing to know nothing would not be armour enough.

He elbowed past a couple arguing about which of them was lying more, then saw a clearing in the press, headed towards it, struck off sideways suddenly and doubled back, offering a prayer to the Saint.

Patron Saint of woodland, of lepers, beggars, cripples and those struck by some sudden misery, of the mentally ill, those suffering falling sickness, nocturnal terrors and of those desirous of making a good Confession – surely, Bisset thought wildly, there was something in that wide brief of St Giles that covered escaping from a pursuer.

The cloaked man cursed. One moment he had the fat little turd in his sight, the next – vanished. He scanned the crowd furiously, thought he spotted the man and set off.

Bartholomew Bisset headed up the High Street towards the Castle, half-stumbling on the cobbles and beginning to breathe heavy and sweat with the uphill shove of it. The street was busy; the English had imposed a curfew, but lifted it for this special night, the Feast of St Giles, so the whole of Edinburgh, it seemed, was taking advantage.

In the half-dark, red-blossomed with flickering torches, people careered and laughed – a beggar took advantage of a whore in the stocks, cupping her grimed naked breasts and grinning at her curses.

Bisset moved swiftly, head down and peching like a mating bull – Christ’s Wounds, but he had too much beef on him these days – half-turned and paused. He was sure he saw the flitting figure, steady and relentless as a rolling boulder; he half-stumbled over a snarling dog tugging at the remains of a bloated cat and kicked out at it in a frenzy of fear.

That and the sheer tenacity of the pursuer panicked Bisset and he swept sideways into Lachlan’s Tavern, a fug and riot of raucous bellowing laughter and argument. He pushed politely into the throng, to where a knot of drovers, fresh down from the north, were starting in to singing songs off key. Big men, they smelled of sweat and earth and wet kine.

The cloaked man ducked in, blinking at the transfer from dark to dim light, the sconce smoke and the reek of the place attacking his nose and eyes – sweat, ale, farts and vomit, in equal measure. He could not see the fat little man, but was sure he had come in here – sure also that the fat man now knew he was being followed, which made matters awkward.

Bisset saw the man, a shadow with a hood still raised, no more than two good armlengths away. He whimpered and shoved the nearest drover, who lurched forward, careering into a clothier’s assistant, spilling ale all down his fine perse tunic and knocking the man off-balance into a half-drunk journeyman engraver, who swung angrily, missed his target and smacked another of the drovers on one shoulder.

The cloaked man saw the mayhem spread like pond ripples from a flung stone. He cursed roundly as a big man, a great greasy shine of joy on his fleshy face, lurched towards him swinging. He ducked, hit the man in the cods, backed away, was smashed from behind by what seemed the world and fell to his knees.

Bisset was already in the backland, stumbling past the privy, hearing the shouts and splintering crashes from inside Lachlan’s. The Watch would arrive soon and he hurried off until he was sure he was safe, then he stopped, hands on thighs and half-retching, half-laughing.

He reached the safety of his sister’s house moments later, found the door unlatched and fixed it carefully behind him, leaning against it and trying to stop the thundering of his heart – yet he was smiling at what he had left behind. That will teach the swine, he thought with savage joy.

He was still laughing quietly to himself when the hand snaked out of the dark and took him by the throat, so hard and sudden that he had no time even to cry out, even as he realised he had not been as clever as he had thought. An unlatched door. On a silversmith’s house – he should have known better …

‘Happy, are we?’ said a voice, so close to his ear he could smell the rank breath. From the side of one eye, he caught the gleam of steel and almost lost the use of his legs.

‘Good,’ the voice went on, soft and friendly and more frightening because of it. ‘A wee happy man is more likely to give me what I need.’

The shadowed man came in through the back court, limping slightly and almost choked by the smell from the garderobe pit. The windows here were wood shutters over waxed paper and no match for the thin, fluted blade of his dagger, but there were bars beyond that, installed by a careful man, with wealth to protect. He moved to the backcourt door, which was stout timbers, nail-studded to thwart savage axes – yet it was unlatched, so that he was in the dark, still room in a few seconds.

He stood for a moment, listening, straining against the thunder of his heart blood in his ears, feeling the matching throb of his cheek and the knuckles of one hand; the drover who had done the first and received the second had the bones of his face broken, but it was small comfort for the cloaked man.

He had come here because it was Bisset’s sister’s house and the place where he had picked up the Edinburgh trail of the fat wee man who had – he was forced to admit – cunningly contrived to thwart him at the tavern.

Now he listened and peered into the grey-black, took a step, then another and stopped when he crunched something under one foot. Glass or pottery, he thought. Smashed. He heard soft scuttling and froze, then heard it again and felt slowly into his belt, fishing out fire-starter and a nub end of candle. He took a deep breath and struck.

The sparks were dazzling in the dark, even through the veil of his closed eyes and, after the first strike, he waited, alert and ready. No-one came; something scuttled at floor level. He struck sparks until the treated charcoal caught, then he fed the wick to the embers and blew until it caught, flaring like a poppy.

He held it up, saw the overturned chair, the smashed crockery, the spilled meal and the mice scattering away from it. He fetched up a fallen candlestick holder, found the fat tallow that had been in it, replaced it and fed that from his nub end.

Better light, held high, flooded yellow-butter around him, glowing sullenly off the rock crystal board and the spill of chess pieces. He turned slowly; gryphon and pegasus stared unmoving back at him, their winking silver bouncing light that turned the tarn of blood to a dark pool. A woman – the sister, he imagined – white face bloody, eyes wide and one of the straw rushes stuck to her cheek with her own blood. Naked and bruised. Knifed, too, the cloaked man saw, with as expert a stroke as he had ever seen – or done himself.

She had let her murderer in herself, quiet in the dark and had not, the cloaked man decided, died easy. Not a lover, then, he decided, but a clever man who knew how to imitate the voice of the woman’s brother. Let me in, hurry in the name of God – he heard it as if he had been there himself, hoarse and urgent in the dark.

She had let him and the stark purple finger marks round her face showed she had been silenced, forced to strip off her flimsy nightdress. Used, he thought, then killed, all without her having said a word.

Yet not silent, all the same. The next body was not far off, a man in his nightshirt – the sister’s husband, armed with a fire iron and fresh from bed, following the whimpers and scuffles of a savage man and a terrified woman. A journeyman silversmith, thinking his gryphon and pegasus were under threat from a wee nyaff of a thief, finding his wife violated, probably already dead, for the red curve along the silversmith’s throat showed he had been taken by surprise. Fixed by the horror of seeing his wife, dead and naked, the cloaked man thought, easy prey for a murderer as ruthless as this one appeared.

He was dry-mouthed and sweating, moved cautiously, rolling along the length of his feet, although he was sure the murderer was long gone, and cursed the brawl in the tavern. He had been lucky to get away from that when the English soldiers from the garrison waded in, cracking heads and shouting. A good trick, Bartholomew Bisset, he thought … you delayed me a long time.

He found the fat man near the door, so near it that he knew Bisset had barely stepped inside before he had been attacked. He had been stripped and lay with his hands above his head and still tied by the blue-black thumbs; looking up, the cloaked man saw the lantern hook and the length of line from it.

Strung up and ill used, he thought grimly, by someone who not only knew the work but liked it and had the leisure to indulge himself, because he knew everyone else in the house was dead.

If Bisset, the poor doomed sowl, had not contrived to delay me with fighting drovers and determined guards chasing me ower the backcourts, I might have been here in time to save him, the cloaked man thought.

He peered more closely, saw the single wound, a lipless mouth that led straight up and into the heart, killing the little fat man so completely and suddenly that he had barely bled. A death stroke, then, from a man with a flat, sharp-edged dirk who had learned as much as he would get, enjoyed as much as he dared and had no more use for Bartholomew Bisset.

The cloaked man heard noises in the street, people passing and calling out to each other, guttural as crows; he blew out the candle and stood, thinking. Nothing here, then. Back to the Lothian man, Hal Sientcler, though the cloaked man was sure that lordling had nothing to do with this.

As he wraithed back out past the choke of the garderobe pit, the cloaked man wondered who did.

The Abbey Craig, Stirling

Feast of Saint Lawrence – August 10, 1297

For two nights the Earl of Surrey’s host had been watching the dull red glow that marked the Scots campfires, across the valley and up to the piously named crag beyond. Like the breath of a dragon, Kevenard had said, which made the rest of the men laugh, the thought of a good Welsh dragon being a comfort to the archers.

Addaf did not think about dragons when he marked it; he thought about Hell and that the Devil himself might be up there for once, when the wind had changed, they all heard the mad skirl and yell of them, like imps dancing.

‘Hell is not up there, look you,’ Heydin Captain had growled, sucking broth off the end of his moustache. ‘Hell will be in the valley, where it is cut about with ponds and marsh and streams. It is there we will have to stand and shoot these folk down and when we start in to it, they will not be singing, mark me.’

In the Keep of Stirling, Sir Marmaduke Thweng watched the ember glow and thought about all the other times he had seen it – too many times, standing in one mass of men about to try to hack another mass of men to ruin.

If he had known Heydin Captain at all, he would have been able to nod agreement to the Welsh file commander; the carse, that low-lying meadow beyond Stirling Bridge cut about by waterways the locals called ‘pows’, was just the place the archers would stand to shoot ruin into the rebel foot.

‘They have no horse at all,’ De Warenne had been told, and the lords who revealed it, shooting uneasy looks at Cressingham and Thweng and Fitzwarin as they did so, would be the ones to know. James the Steward and the Earl of Lennox, fresh from negotiating their way back into Edward’s good graces, now offered to try the same with Sir Andrew Moray and Wallace.

‘I doubt it will do much good,’ De Warenne declared, ‘since Moray might grovel his way back to his lands and titles, but Wallace will not be granted anything, my good lords. Not even a quick death.’

‘For all that,’ Lennox said morosely, ‘it would be worth the try and you lose nothing by it – you are waiting for Clifford.’

‘Ha,’ snorted Cressingham and De Warenne shot him an ugly glare. Thweng said nothing, but he could see the two Scots lords look round them all, then to each other. No-one offered an explanation, but Thweng knew, as they left, that they would find out soon enough – Robert De Clifford, Lord Warden of the English March and the man who had been assiduously gathering troops for the Earl of Surrey’s host, had been sent packing by Cressingham. He had been turned back as ‘not needed’, Cressingham ranting about the cost of defraying Clifford’s expenses when the army was already large enough to deal with a rabble under a mere brigand.

That had been before they set out, of course and between Roxburgh and Stirling, the great army had melted like rendering grease and the countryside for miles around, in a broad band along the road, was filled with plundering deserters and stragglers.

Now they needed Clifford and that outraged lord would not come even to piss on a burning Cressingham.

Thweng left De Warenne and Cressingham arguing about dispositions and went out into the wind-soughed night, high on the battlements of the castle where sentries marked steady progress between flickering torches. He wondered if he would have to fight anyone he knew tomorrow.

Out on the road to Cambuskenneth’s Abbey, far enough from Craig for the fires there to be pale flowers in the dark, Bangtail Hob wrapped himself tighter in his cloak and brooded, half-dreaming of Jeannie the miller’s daughter, who could get you cross-eyed with just hands and lips. It was a fair trod to get to her at Whitekirk, but worth the shoeleather … he heard the hooves on the road and raised his head above the tussocks he hid behind.

The wind sighed, damp off the carse, and the loop of wide river was a black shining ribbon in the last light. The rider, hunched on the back of a plodding mount, was a silhouette heading down to the great campanile tower which marked where the abbey stood.

Since the only road led down from under the Abbey Craig, it meant the visitor had come either from the Scots camp, or across the brig, up the causeway and along under the Abbey Craig. There had been a few desperate refugees earlier, all handcarts and hurry, but none for some time.

Bangtail watched the rider vanish towards it, then settled back into his half-dream. Stop folk getting out of the Abbey, he had been told – so anyone coming in was not a problem. He glanced up to the distant balefire lights of Stirling’s hourds, then across the stretch of dark to the flowered blossom of fires on the hill and wondered what it might be like to be there, waiting on the morrow.

He was certain Sir Hal knew what he was about, trying to avoid the great scourge of soldiery coming up on Stirling, full of vengeance against all matters Scots. Heading for the rebel camp was dancing along a thin edge, all the same – on the one hand, Hal would be seen as a Bruce man and so on the English side. On the other, he had the Countess of Buchan with him and she was the wife of the Earl who, if not actively supporting Wallace and Moray, had contrived to turn a blind eye to their doings, permitting them to unite here.

There were other reasons, Bangtal Hob was sure – or else why would he be sitting here, making sure no wee stone carver crept out of Cambuskenneth in the dark? Yet he did not fully understand them – nor needed to. He had been told what to do and he settled to it, huddling into his cloak against the chill.

Up on the crag, Dog Boy sat in the lee of the striped tent, watching the nearby fires and, beyond that, the little red eyes, like weasels in a wood, that marked where the English walked the walls of Stirling Castle.

He sat listening to the nearby men chaffering each other, arguing about this and that, fixing leather straps, honing the points of the great long spears. He had been watching the spearmen, fascinated, for days; they were being drilled in how to work together, hundreds and more in a block. Level pikes. Ground pikes. Support pikes. Butt pikes. Charge pikes. The Dog Boy had watched them stagger round, clashing into each other, cursing and spitting and tangling up.

Some, he saw, were more advanced than others – the men of Moray’s army – and these were a joy, moving and turning like a clever toy. Wallace’s kerns did not like the work, but were whipped to it by the lash of his great booming voice and the expert eye of Moray’s commanders.

Hal sat nearby and watched the Dog Boy watching the flames of cookfires flatten and flicker in the wind up on Abbey Craig. He was waiting to speak to Wallace and curiosity -Christ, now there was a curse on him – had driven him within earshot of the tent, where he could hear the arrived lords try to persuade Wallace and Moray to give in.

‘So you stand with the English,’ Wallace said and Hal heard Lennox and John the Steward splutter their denials through the canvas.

‘So you stand with us.’

This time there as silence and then Moray’s bland, calming voice broke a silence so uncomfortable Hal could feel it from where he sat.

‘You have our thanks, my lords,’ he said in French. ‘Take to Surrey our fervent wish that he withdraws from here and the realm.’

‘Surrey is not the power here,’ John the Steward answered, ‘Cressingham will lead the army in the morning.’

Wallace’s laugh was a bitter bark.

‘He is no leader of men. He is a scrievin’ wee scribbler, who would skin a louse for the profit of the hide,’ he growled. ‘Tell him that, if ye like – but mark me, nobiles, there will be no repeat of Irvine here.’

‘Those negotiations held the English there. Bought you the time for all this,’ Lennox answered sullenly in French, and Hal heard Wallace clear his throat, could almost see the scowl as he made it plain he wanted no more French here, which he could understand much less than English. Quietly, Moray translated.

‘You bought your lands back,’ Wallace answered bluntly. ‘With a liar’s kiss and betrayals. Soon, my lords, you will have to choose – tak’ tent with this; those come last to the feast get the trencher only.’

‘We will not fight with ye, Wallace,’ the Steward said defiantly, preferring to irgnore the insults. ‘It is the belief of the community of the realm that a peaceful settlement is by far the best, no matter the considerations.’

‘That will never be from my hand,’ Wallace answered, bland as mushed meal and speaking in carefully modulated English. ‘I wish you well of your own capitulation. May your chains sit lightly on you, my lords, as you kneel to lick the hand. And may posterity forget you once claimed our kinship.’

There was silence, thick as gruel, then a voice thicker still with anger; the Steward, Hal recognised, barely leashed.

‘You have nothin’ to lose, Wallace, so casting the dice is hardly risk from your cup.’

‘And from mine?’ Moray asked lightly. There was silence.

‘We will not stand against ye,’ Lennox persisted.

‘So declared another of your brood, Sir Richard Lundie, afore he leaped the fence to the English,’ Wallace answered, his voice bitter. ‘He now thinks Edward is the braw lad to put this realm in order and has joined them to fight us. That is what came of your antics at Irvine. If you fine folk persist in grovelling, there will be a wheen more like him.’

‘By God, I’ll not be lectured by the likes of you,’ the Steward thundered. ‘You’re a come-lately man, a landless jurrocks with a strong arm and no idea of what to do with it until your betters tell ye …’

‘Enough.’

Moray’s voice was a harsh blade and the silence fell so suddenly that Hal could hear the ragged bull-breathing through the canvas.

‘Go back and tell the Earl of Surrey, Cressingham and all the rest that we await their pleasure, my lords,’ Moray added, gentle and grim. ‘If he wishes us gone from here, let him extend himself and make it so.’

Movement and rustle told Hal that Lennox and the Steward had gone. There was silence, then Wallace rumbled the rheum out of his throat.

‘Ye see how it is?’ he declared bitterly. ‘Apart from yourself, the community of the realm spits on me. We can never mak’ Wishart’s plans work if there is only us pushin the plough of it.’

‘Never fash,’ Moray said. ‘For all they think it, it is not the community of the realm who fight here the morn. It is the commonality of the realm and you are their man. Besides – the nobiles of this kingdom follow us because neither the Bruce nor the Comyn can walk in the same plough trace. In the end all we have is a king, for Longshanks has broken Scotland’s Seal, stolen the Rood and purloined the very Stone of kings. There is no-one else to dig the furrow, so we must.’

The Dog Boy had only half-heard this, understanding little, watching the feet come and go. He was an expert on feet, since it was usually what he saw first from the rabbit crouch he always adopted, halfway between flight and covert.

He saw the horn-nailed bare feet of men from north of The Mounth, who scorned shoes for the most part save for clogs or pattens in the deep winter. These were the wild-haired men with wicked knifes and round shields and long-handled axes, who spoke either a language the Dog Boy did not understand at all, or one which he recognised only vaguely. They sibilated in soft, sing-song tones and made wild music to dance to.

There were turnshoes and half-boots, ragged and flapping some of them, belonging to men from Kyle and Fife and the March. These were the burghers and free men, ones who could afford iron hats and fat-padded jacks with studs, the ones who carried the long spear, the pike, in the marching formations which so fascinated the Dog Boy. Schiltron. It was a new word, to everyone else as much as the Dog Boy; he rolled it round his mouth like a pebble against thirst.

The men from Ayrshire and those from Fife contrived to sneer at each other for their strange way of speaking – and both walked soft around the men from the north. Yet they were here, all facing the same direction, and the Dog Boy was aware, as if he had lain back in grass and started to look clearly at clouds, of the vastness of that revelation.

They were here because, for all they might dislike each other and the men from north of The Mounth look on the likes of Bruce and Moray and Comyn as incomers, the one thing they hated more was the idea of being ruled by invaders from the English south.

The Dog Boy had also seen the fine leather boots, or the maille chausse with leather sole that marked a knight or man-at-arms, but there were precious few of those iron leggings. He had thought of Jamie Douglas then and had asked round the campfires until he had found men from Lanark, one of whom knew the tale of it.

‘Away to France,’ he told the Dog Boy in the guttering red light. ‘Away to safety with Bishop Lamberton, since his da is taken off in chains.’

The man who told the Dog Boy looked at the boy’s pinched, sunken-eyed face as he added that Jamie’s da was unlikely to be seen again, carried off to the Tower from his cell in Berwick, where he raved, ranted and finally annoyed his gaolers once too often. Beatings, he had heard, and worse. The Hardy would not be back in a hurry, his woman and Jamie’s siblings were living with her relations, the Ferrers, somewhere in England – and Douglas was now an English castle.

The Dog Boy had wandered in a daze back to the lee of the striped tent where Hal found him. Douglas held by the Invaders. Jamie in France. The Dog Boy only had a vague idea that France was somewhere south of England, which was south of Berwick; it seemed a long way off, even if the high and mighty spoke the language of the place to one another and there was actually a man from France here, on Abbey Craig.

In the middle of the flickering fires, like roses in the dark, the men huddled close and the Dog Boy felt utterly alone, felt the great, black brooding of the surrounding trees, sighing and creaking in the dark.

Jamie, Douglas Castle – everything he had known was gone, even the Lothian lord’s fine dogs. Now most the few men he knew – Tod’s Wattie and Bangtail and the others – were far across the night and the swooping loops of the river, down where the faint pricking lights marked Cambuskenneth Abbey. He was glad that Sim and the Lord Hal were close.

‘Get yourself to Sim,’ Hal said to the huddled Dog Boy, the tail-down hunch of him wrenching his heart. ‘He is by a fire with something in a pot.’

The Dog Boy went into the night. Hal heard the tent rustle again as Moray left it and then Wallace’s bass rumble slipped through the canvas.

‘Ye can stop skulking at the eaves, Hal Sientcler, and come and tell me about a stonecarver.’

Wearily, Hal levered himself up and went in to where the air reeked of stale sweat and wet wool. Wallace lay slumped in a curule chair, the hand-and-a-half no more than a forearm length from his right hand. He listened as Hal told him about the Savoyard stonecarver.

‘Forty days, is it? We never have forty days, Hal. We have the night and the morn and, God willing, if battle be joined as we wish it, the morn’s morn.’

Hal shifted slightly and inwardly cursed the great giant lolled opposite. He wore better clothes these days – even hose and shoes, as befitting one of the saviours of the realm – but it was still the same brigand Wallace.

‘I can hardly assault Cambuskenneth,’ Hal declared. ‘The man has sanctuary for forty days. He has thirty-seven of them left. He cannot get out without being seen, for I have posted men to watch every way away from the place.’

Wallace heaved a sigh and shook his shaggy head.

‘The army had been here a week waiting for the English to relieve out threat against Stirling. I cannot believe the man was under my nose for that time,’ he said and then grinned ruefully. ‘Ye did good in tracking him, more praise to ye for that.’

Hal did not feel comforted; it had not exactly been difficult to work out that Manon de Faucigny would head for the abbey at Stirling – Cambuskenneth was perfect for a man of some quality, with skills and tools specific to kirk stonecarving and the history of having worked at Scone.

Since he was a Savoyard, it was not hard to find out that he was in residence – but the questioning had revealed their presence and the abbot, initially smiling and helpful, returned grim-faced to tell Hal that the man they sought was now in sanctuary. In forty days, he would have to leave, until then he was inviolate. He did not want to see or be seen by Hal or anyone else.

‘Well,’ Wallace answered. ‘After the morn, all matters will be resolved, win or lose. The abbey included.’

Hal did not doubt it; here was a man who had sacked Scone, who had burned Bishop Wishart’s house – in a fit of temper some said, after hearing that his mentor had given in at Irvine. The likes of an abbey was no trouble to the conscience of a man like that, yet Hal did not like the idea of sacking it and said so.

‘A wee bit too much brigand for ye, Sir Hal?’ said Wallace, his sneer bitter and curled.

‘Did clerics do ye harm afore?’ Hal countered, stung to daring. ‘When ye were up for the priesthood?’

Wallace stirred from his scowling and grinned, slack with weariness.

‘No, no – I was a bad cleric always – though a good man, John Blair, tried to put me on the path. But my wayward young nature had mair affinity with Mattie.’

He glanced up and smiled wryly.

‘Son of my uncle, who was a priest,’ he added. ‘Like all such, he was neither sheep nor wolf and suffered because of it. Wanting no part of priesthood and yet stepping into the robes, like myself. What dutiful sons we were – I am sometimes sure that bairns weep at birth because they know the estate they are born into.’

Hal recalled the few priests sons he had known, pinch-faced boys living in a nether world where they were unacknowledged and yet given the advantages of rank as if they had been. Even Bishop Wishart had sons, though no-one called them anything other than ‘nephews’.

‘Mattie,’ Wallace went on, dreamy-voiced with remembering, ‘showed me the way of survival as an outlaw, mind you, so the life clerical was not all wasted time.’

Hal had heard vague tales of the wayward Wallace, of the robbing of a woman in Perth. He mentioned it, quivering on the edge of fleeing at the first sight of black on the Wallace brow.

‘She was a hoor,’ Wallace admitted ruefully. ‘She robbed us – but it did not look good, a fully fledged cleric regular and a wee initiate boy visiting her in the first place. So we took what we could and ran. Not fast enow, mind – but since Mattie was a priest and I was so young, they let us off.’

‘Is that why ye gave Heselrig a dunt, then?’ Hal asked. ‘I had heard it was because of a wummin.’

‘I have heard this,’ Wallace answered slowly. ‘No wummin and no petty revenge for an assize that freed us. I went after Heselrig because he went after me – I had a stushie with a lad who fancied I had no right to wear a dagger and made his mind up to remove it.’

He paused and shook his head – in genuine sorrow, Hal saw.

‘I was a rantin’ lad then, a hoorin’ brawler in clericals and aware that the cloots did not fit me. I did not want the Church, Sir Hal, nor did it care much for me – but there was little other course open for a wee least son of a wee least landholder.’

He paused, frowning and pained.

‘I did no honour to my father with such behaviour and am not proud o’ it.’

‘What happened?’ Hal asked. ‘With the lad ye argued with?’

Wallace glanced up from under lowered brows, then stared back at the scarred planks of the floor.

‘He was a squire to some serjeant in Heselrigg’s mesnie, who contrived the quarrel in order to put down a wee strutting cock of a Scottish lay priest.’

He stirred at the memories of it, hunched into himself like a great bear.

‘It should have been a matter for knuckles and boots, no more,’ he went on bleakly. ‘Yet there was a dirk involved in the quarrel and, in the end, I gave it to him – though it did him little good, since it was buried in his paunch. He did not deserve such a fate and the Sheriff of Lanark agreed. No matter my guilt – aye and shame over the affair – I was not about to stand around like a set mill and be assized for it. So matters took their course.’

He was silent for a time, then shook his head and stirred.

‘Such tales do not endear me to the nobiles, he noted grimly. ‘They have no use for a wee outlaw, a landless apostate clerical of the Wallaces.’

‘Hardly wee,’ Hal returned wryly. ‘Betimes – ye have a wealth of brothers and cousins, it appears.’

‘Peculiarly,’ Wallace said bitterly, ‘this is timely with my elevation to the status of Roland and Achilles. I could not beg a meal at Riccarton, Tarbolton or any other Wallace house afore now. Only Tam Halliday in Corehead ever gave me room and board and he was kin only by being married on to my sister.’

He yawned and his eyes half-closed, so that Hal saw the weariness slide into the etched face of the man. Tomorrow, this giant would take the weight of the kingdom on his broad shoulders and lead Scotland’s army against their enemy.

Tomorrow, I will be gone from here, Hal thought. I can leave the Countess here and say I delivered her as far as safety allowed – which was no lie, he tried to convince himself. If I had taken her to the English in Stirling, only to find her husband was now actively a rebel, I would have delivered her into the hands of his enemies. Taking her to the rebels on Abbey Craig, on the other hand, placed her in hands which, at least, would not use her as ransom. Yet.

Not for the first time, Hal cursed the whole uncertain business, as he had done, silent and pungent under his breath, all through the town, under the brooding scowl of the English-held castle and out over the brig to Abbey Craig.

Yet he remembered the long days up to Stirling as ones marked by glory. As Sim said when they were rumbling up Bow Street, you would not think the world was about to plunge into blood and dying.

‘You will be wishing yourself back behind the plough, Lord Hal,’ Isabel said to him, gentle and smiling. He was glad of the smile, since it had been fading the closer they got to the northland of Buchan.

Back at Herdmanston, Hal said, it would be the barley harvest, the big one of the year. With luck, he told her, there would be no scab on sheep, or foot-rot, or cracked udders on cattle, or staggers or overlaid pigs. Even as he spoke, he felt the crushing weight of knowing that there were too many men away from home and not enough to get the harvest in, a tragedy repeated across every homestead in Scotland.

Every day the sky was faded blue, streaked with thin, cheese-muslin clouds. The barley and rye was ripening, waiting to be reaped, tied and winnowed without blight or burning, just enough rain had fallen to turn the millwheels and fill the rain-butts. Yet the land was empty, for everyone was with the army.

Yet the memory of Herdmanston bleared him as he spoke. You will, he told her, feel the first breath of autumn, cool, but not cold. It would be a place of precious metals, the sun shining through a soft silver, lying green-gold on the harvest fields. In a sea of haze, great iron bull’s head clouds would float up from the west and the breeze, he added, has a trick of rising suddenly, running through the trees.

She listened, marvelling at the change in him when he spoke of the place, finding that same strange leap deep in her.

There would be sunsets, he began to tell her – then stopped, remembering the last one he had seen, etching the stone cross stark against the dying blaze of day.

She knew of the dead wife and son from others.

‘What killed them?’ she asked and the concern in her voice robbed it of sting.

‘Ague,’ Hal answered dully. ‘Quartan fever – she died of the same disease as Queen Eleanor, my boy a week after his mother. I had the idea for the stone cross from all the ones the king put up for her.’

‘Longshanks loved her,’ Isabel said, ‘hard man though he is.’

‘Aye,’ Hal said and shook himself from the memories. ‘We share that pain, if little else.’

‘One other thing you share,’ Isabel said impishly, ‘is a horse. The king’s favourite horse is Bayard and the Balius you ride is from the same stock.’

Bayard, Hal knew, was the name of a magical bay from children’s stories, a redhead with a heart of gold and the mind of a fox and would have been a good name for Isabel herself. He said as much and she threw back her head and laughed aloud, a marvellous construct of white throat and rill that left Hal grinning, slack and foolish.

‘I heard he rode Bayard at Berwick,’ Sim growled, coming up in time to hear this last, crashing into it like a bull through a bad gate. ‘Leaped the wood and earth rampart and led his men in for the slaughter, so it is said. We are nearly at St Mary’s Wynd – do we cross the brig and join the rebels up on Abbey Craig?’

‘Join the rebels,’ she had said and laughed.

Hal shook himself from his revery, back to the present. Easy for you to laugh, Lady, he thought bitterly, who are never done rebelling, one way or another. Yet I have been charged to see you safe and so it must be …

Wallace had nodded off and Hal felt a sharp sympathy with the sleeping giant, hair spilling over his face, one grimed fist a finger-length from the hilt of the hand-and-a-half. Keeping all these men together was a hard enough task, never mind trying to turn them from fighters into soldiers, trying to outthink the enemy, trying to plan how to win a battle against the finest cavalry in the world.

Join the rebels. By God, not again, Hal thought. Bringing the Countess here was the safest course for her, Hal thought, since her husband was a Comyn and so more kin to the rebels than English Edward. Now that it was done …

He stepped out into the night air, hearing the strange, wild sound of sythole and viel and folk wheeching and hooching in a dance, as if tomorrow was just another day, with time enough to work off a bad head. The world was racing towards dawn and Hal felt a leap of panic to be away from here before light …

‘Let us hope they dance as well the morn,’ said a voice and Hal spun to where Moray stepped from the shadows. He was young, thick-necked and barrel-trunked and would go to fat like his da, Hal thought, when he got older. For now, though, he was a solid, formidable shape in fine wool tunic and a surcoat with a blue shield and three stars bright on it, even in the dark. Behind him came the foreign knight who spoke French but was Flemish with some outlandish name Hal scourged himself to remember.

‘He’s asleep,’ Hal said jerking his head back into the tent. Moray nodded and shrugged.

‘No matter, the ring is arranged and all that remains is for us to take our partners and jig.’ Moray said, breaking into French for the benefit of his companion, then paused, a smile, half-affection, half bitter rue on his face.

‘I came to make sure The Wallace followed the steps,’ he added. ‘He has a habit of dancing away to his own tune.’

‘Will you join us tomorrow, Lord Henry?’ the foreign knight asked and Hal blinked, then realised the knight – Berowald, he remembered suddenly, Berowald de Moravia, the Flemish kin of the Morays – was inviting him to be part of the hundred or so horse, all that the Scots army possessed and almost none of it heavy warhorsed knights and serjeants.

He shook his head so vehemently he thought it might fall off. Balius belonged to Buchan and could not be risked in a battle like this, he babbled, while Griff was too light to be of much use. Andrew Moray nodded when this was laid out.

‘Aye, well, it will be a painful dunt of a day,’ he declared grimly, then nodded to Berowald as he spoke to Hal.

‘The winning of it,’ he added in French, ‘will depend on the foot and not the horse, for all my kinsman here wishes it otherwise.’

Berowald said nothing, but the scowl spoke of his distrust at relying on ragged-arsed foot soldiers who were wildly dancing away the night before they had to stand and face the English horse. A thousand lances, Hal had heard, and he shivered. A thousand lances would do it – Christ, half that would plough them under, he thought.

He thought of Isabel and what would happen to the camp and the women and bairns in it if the battle was lost and panicked at that – the pull of her was iron to a lodestone.

She was in with the Grey Monks, the Tironensians from Selkirk, who had made a good shelter from tree branches and tent cloth, consecrating it into both a chapel and a spital for the sick and, soon, the dying. Hal found her arguing with a frowning cowl about how best to treat belly disease.

‘Chew the laurel leaves, swallow the juice and place the mulch on the navel,’ she said wearily. ‘He chews the leaves and swallows, not you. I would not stray far from the jakes now if I were you.’

The monk, pale faced in the shadows under the cowl, nodded and reeled away; Isabel turned to Hal, raising eyes and brows to the dark. She jerked her head and he followed her to a curtained-off chamber, where, once inside, she hauled off her headcovering and scrubbed the spill of dark unbraided red-auburn hair which fell to her shoulders, like a dog scratching fleas and with every sign of enjoyment.

‘God’s Wounds, that feels good,’ she exclaimed. ‘All I need now is a chance to wash it.’

She became aware of Hal’s stare and met it, the headcovering dangling in one hand like a limp, white snakeskin. Under his frank, astonished stare she felt herself blush and became defiant.

‘So?’

‘My … I am sorry … you took me by surprise,’ Hal stammered and turned his back. She snorted and then laughed.

‘There is not much you do not know of me now, Hal. Whore of Babylon is the least of it. Unhappy wife, certes. Unhappy and spurned lover. Showing my unbound hair to man not my husband or kin is the least of it.’

She sank on a long bench. ‘No worse than having to be restrained by outraged monks from actually putting a mulch of leaves on a sick man’s navel.’

‘I was not expecting the hair,’ Hal said.

‘I admit it needs a comb and a wash,’ she answered, ‘but surely it is not as ravaging as a basilisk to the eye?’

‘No … no,’ began Hal, then saw her wry little smile. ‘No. I was not expecting so much of it – I only saw it once down and in the …’

He stopped, realising the mire he had blundered into and the widening of her eyes.

‘When was this?’

He felt himself prickle and flush.

‘Douglas,’ he admitted. ‘I saw you and The Bruce … young Jamie’s shield and gauntlet …’

It was her turn to redden.

‘You were spying on me,’ she accused and he denied it, spluttering, then realised she was laughing at him and stopped, scrubbing his own head ruefully.

‘Aye,’ she said, seeing this, ‘the pair of us will have to shave like clerics to rid ourselves of all that is living in it.’

‘Like your spital,’ Hal answered, straight-faced, ‘it seems to have offered space to all the poor souls who can cram in.’

Now it was her turn to smile and the sight warmed Hal. Outside, someone started to scream and Isabel’s head came up.

‘Maggie of Kilwinning,’ she said, frowning. ‘Her man is with Moray’s mesnie. She was brought in raving about tigers of flame tearing her body. Four other pregnant women were brought in, spontaneously aborting. Three of them will probably die.’

Her shoulders slumped and he found his hand on her head before he knew he had even done it. She straightened and looked at him, halfway between flight and astonishment. He took it away and then she stirred and smiled.

‘I would wash that if I were you,’ she said.

‘There are those who will say it is possession by demons,’ Hal offered cautiously. ‘A punishment for the sin of rebellion. A sign, perhaps, that God has forsaken us.’

‘Bollocks,’ said Isabel savagely and Hal jerked. Their eyes met and both smiled.

‘So,’ Hal said finally. ‘A sickness. Of the mind, perhaps? The madness of the doomed?’

It was shrewd and Isabel acknowledged it with a nod of approbation into those cool, grey eyes. Then she shook her head.

‘There are herbs that do that, though not so violently as this.’

‘Poison, then?’ Hal suggested and they looked at one another. She knew he was thinking of his dogs and Malise; for a moment she shivered, then shook it off.

‘No,’ she answered, ‘nothing so murderous – St Anthony’s Fire.’

Hal had heard of it though he did not know what it was.

‘The curse of a saint,’ she said. ‘Which is never dismissed lightly. Ask the Earl of Carrick.’

she sighed and rubbed her tired eyes.

‘One day we will find how the saint does it and why it is always the poorest of the sma’ folk who suffer. I have no proof of it, but I suspect the bread. Or the herbage they put in potage. The poor do not have the luxury of refusing even the stuff that looks worst.’

‘You know a deal on medical matters,’ Hal said and she looked sideways at him.

‘For a Countess, you mean? Or for a woman?’

‘Both.’

she sighed.

‘Well, remember I was once the daughter of MacDuff. My father was murdered, by his own kinsmen. The true lord of Fife is a a wee boy and a prisoner in England. I had no great expectations, even of a good marriage and, certes, not one by choice of my own hand.’

‘Unlike Bruce’s mother,’ Hal said tentatively and saw the flicker of her lips at the memorable tale of how the Countess of Carrick had kidnapped the young man, Bruce’s father, come all the way from the Holy Land to tell her that her first husband, Adam de Kilconcath, had died.

‘Aye – maybe I should have followed her and locked up the son until he agreed to carry me off,’ Isabel sighed. ‘Then, he is not his father and holds that kidnapping up as yet another indication of how little spine his father has, to be so overcome by a woman.’

‘Would it have been worth it, such a kidnap?’ Hal asked cautiously.

‘No, for certes,’ she answered with a frankness that stunned him. she saw his face and managed a grim little smile.

‘Once I thought there was love in it, but I always thought the Earl of Carrick was as good a refuge from the Earl of Buchan as I would find,’ she said and her face darkened as she spoke of Buchan. ‘That one behaves as if I was a dunghill hen to his rooster – the day he realises I cannot give him the egg he wants will be the one that dooms me to a convent, I am thinking. As you can see, lord Hal, I am not suited to a cleric life.’

‘You cannot have childer?’ he blurted and the concern in it was balm enough for her to reply without anger.

‘It would seem not,’ she answered. ‘I am young yet, but women with those years on them have a brood and more.’

The bitterness in it was a wormwood Hal could almost taste himself, so he sought to dilute it.

‘Or are dead in the birthing,’ he pointed out, then saw the bleak that scorched her eyes grey as ash.

‘Better that,’ she said softly and he saw the lip tremble, just the once.

‘So – this is why you study the medical?’ he asked hastily, levering matters back on track.

‘At first,’ she answered flatly, ‘but that was not for a daughter, let alone one of Fife. I contrived a deal of it on my own, though books and treatises are hard to come by – and none of it was any help. Strangely, as the Countess of Buchan I had better freedom to indulge it and my own house at Balmullo.’

She stopped and he saw the beautiful eyes of her pool with tears, which she shook away with an impatient gesture.

‘I have books there and kept Balius stabled at it,’ she went on. ‘My husband will want to burn it to the ground after this unless I prevent him.’

Hal did not want to know how she would prevent him. He did not want to know that she was returning to Buchan at all, or that he was the jailer taking her. Yet the thought of what might happen if the English stormed into this camp, all vengeance and victory, made him take her by the hand, so suddenly that it was moot who was more surprised by it.

‘We could leave,’ he declared. ‘Tonight – afore the battle …’

She blinked once or twice, disbelieving – then the great warm rush of it hit her like a wave and it did not matter if they stayed or left, only that he had offered. She took her hand back, gently.

‘You have done enough, Lord Hal,’ she said and meant it. ‘Go home. As I must.’

There was silence, long and aching.

‘I even contrived to have a master from Bologna visit once,’ she declared, suddenly brittle bright. ‘The Earl was pleased, since it would keep me from shaming him at home.’

‘Bologna?’

‘Buchan no doubt hoped I would find humility, but I was gulling him. I said he was a priest from Rome.’

She broke off, sighed and shook her head.

‘I have treated Buchan poorly and have sympathy for the man,’ she added bleakly, ‘but only to the point when he goes red in the face and punishes me, one way or another. Yet I have treated him as ill, in my way.’

‘Does this excuse beatings?’ Hal growled. ‘A knight is supposed to protect a lady.’

Isabel smiled sadly.

‘Ah, would it not be nice if the world was Camelot,’ she answered. ‘It is not, of course, so I cheated him to get this Master Schiatti from Bologna, for the best medical teachers are there at the University. What in the name of God and all His Saints I thought to do with what he taught I do not know -but I learned, among other matters, that even the most recalcitrant can be persuaded, for a price, to teach some of their art to a woman. Some of it was valuable, other aspects less so. I was good with the astrology, but mediocre with pigs at best.’

‘Pigs?’ asked Hal. Talking to this woman was like learning to skate on thin ice.

‘Nearest to humans in anatomy and skin and bone,’ Isabel replied. ‘In Bologna, real corpses are kept for examinations and most everyday work is done on pigs. Strangled, burned, poisoned and buried for a day, a week, longer. Bologna is a dangerous place to be a pig, sir Hal.’

‘If I ever take sim Craw to the Italies, I will bear it in mind,’ Hal said laconically, ‘since his manners clearly endanger him with dissection. Mark you – it seems Balmullo is no place to root for acorns either.’

she looked at him sideways a little.

‘You are not fond of physickers?’

Hal started to deny it, unwilling to annoy this woman, but the truth choked him. The ague was a pest which began as innocent as a shiver on a warm day, as if some sudden unseen breeze had caressed the spine. In three days or less, the shiverers were rattling their teeth on a rack of sweat-soaked bedding, the air in their chest wheezing like leaky forge bellows. They complained of the cold and burned away to a greasy husk before your eyes.

Others got it, too – from the vapours of the fetid, warm marshes according to the physickers and lazar priests – and some of them died swiftly, while others were abandoned even by their fearful priests and died of neglect.

One, the lovely young Mary of the saltoun Mill, crawled from her sickbed and slipped into the river, drawing the cool water over her like a balming coverlet. After they found her, the same saltoun priests who had abandoned her refused her consecrated burial, since she had taken her own life.

Not that they were any use when they found the courage to remain with their charges. Rosemary and onions, wormwood and cloves, vinegar and lemons, all mixed with henshit like some bad pudding or capon stuffing and smeared on the forehead and under the arms.

A live toad, fastened to the head. A live pullet, cut in two and held, bleeding and squawking, to anything that looked like a sore – though sores were no part of the ague that took Hal’s wife and son, only a shaking sickness that boiled them away to wasted sweat, to where death was a merciful release.

She listened to him in silence, feeling the bile, the venom pus of it. When he had finished, she laid a hand on his arm and he felt strange and light-headed.

Another scream echoed and he saw her leap up, then waver uncertainly before recovering.

‘Have you eaten?’ he asked and she stared at him for a moment, then shook her head.

‘Well, if you provide the wine, I will provide some oatcakes and a little cheese,’ he said with forced cheer.

She didn’t argue, so that they sat in a makeshift House of God and ate.

‘Cygnets’ Hal said, rinsing the cling of oatcake from the roof of his mouth.

‘What?’

‘Cygnets,’ Hal repeated. ‘A teem of cygnets. The game you like to play.’

He saw her face flame and her head lower. The oatcake turned to ash in his mouth.

‘Pardon,’ he stuttered. ‘I thought …’

It tailed off into silence and he sat, mouth thick with oats he could neither spit nor swallow.

‘It was a silly game for lovers,’ Isabel said at last and raised her head defiantly, staring him in the face. ‘To see who would be horse and who the rider.’

Hal forced the lump down his throat, remembering as he gagged, the high table at Douglas and her triumphant shout as she beat Bruce with her blush of boys. Ha, she had declared. I come out on top.

He found her hand thrust at him and a cup in it.

‘You will choke,’ she said and he forced a smile.

‘Water,’ said Hal with certainty, ‘has fish dung in it.’

Then raised the cup in salute and drank.

‘Which is as good a reason as any to avoid it and keep to wine.’

‘That is Communion wine,’ Isabel said wryly and Hal spluttered, then put the cup down carefully, as if would bite him. Isabel chuckled.

‘You have already swallowed enough to be allowed to sit at the feet of Christ Himself,’ she said and Hal found himself grinning. They could both be ducked, or even burned at the stake for what they did here, drinking Holy wine and laughing blasphemously, her unchaperoned.

‘shrews,’ she said suddenly and Hal blinked. The silence stretched and then she raised her head and looked into his grey eyes.

‘A rebel of shrews,’ she declared and added softly, ‘I win.’

The thunder of blood in his ears drowned the sudden arrival, so that only the blast of air snapped the lock of their gaze. Like the opening of a chill larder door, the man crashed in on them.

‘Ah might have weel kent ye would find the cosiest nook,’ growled the voice. ‘Wine and weemin – I taught ye well, it appears.’

Hal whirled, as if caught fondling himself in the stable, stared up into the fierce, grey-bearded hatchet face.

‘Father,’ he said weakly.

The Abbey Craig, Stirling

Ninth Sunday after Pentecost, Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity – August 11, 1297

They came to him just before dawn, as the sky lightened in a sour-milk smear, two earnest men already accoutred for war and clacking as they walked. Thweng watched them, seeing the grim eagerness in their hard young eyes, flicking over the blazons that let him know who they were. In the midst of their differing heraldry, a little badge in common – st Michael with flaming sword.

‘The Wise Angels request a boon,’ one of them said, bowing, and Thweng sighed, trying not to let it out of him in a weary puff. Mummery. Chivalric posturing from folk gripped by Arthur and the Round Table – yet, beneath it, the very real courage and skill that might win the day. So he forced himself. ‘Speak, Angel.’

‘The Wise Angels request to be your boon companions in the Van this day, lord.’

‘How many angels ride at my shoulder?’

‘Twenty, lord. Sworn under Christ.’

‘Welcome, Angels.’

He watched the men clack happily away. The Wise Angels were one of many little companies of knights who swore oaths to do great deeds of bravery on the eve of battle, although Thweng knew these were one of the better ones, composed of tournament-hardened knights. They had come to him, one of the foremost fighters on the circuit – and commander of the Van horse.

They had taken their name after Christ’s rebuke to Paul when men arrived to arrest them and Paul wished to fight. ‘Do you not think,’ Christ had said, ‘that, if I had asked, my Father in Heaven would not send me a legion of wise angels, against whom no man will stand?’

Today, a legion of twenty Wise Angels, against whom no man will stand, would ride at Thweng’s shoulder, swelling the numbers of barded horse under his command. The Fore-Battle, the Van, would be led by Cressingham, around two thousand foot and Thweng’s one hundred and fifty heavy horse designed to plant themselves firmly on the far side of the long brig and allow the Main and Rear battles, another two hundred knights and sergeants and four and a half thousand spearmen and archers, to form up under Barons Latimer and Huntercombe.

After that, it would simply be a matter of shooting the Scots to ruin and then riding the remnants into the dust.

It would have been simpler still if half the army had not melted away on the road up from Roxburgh and most of the rest sent home by the Treasurer on grounds of cost. Now the forces arrayed opposite each other were roughly equal, though Thweng knew the heavy barded horse and their lances would be the deciding factor. All the same, there were far fewer than he would have liked and Cressingham bore the blame for that.

Thweng heard the low, beast-grumbling groan of the army surfacing into the day, saw the spark of hasty fires in an attempt by some to get warmth in their bellies. Somewhere across the slow, ponderous loops of the river, he heard bells pealing. It is the Sabbath, he remembered suddenly.

Across the looped river Scots knelt while the wind ruffled through them as if in a forest. The Abbot from Cambuskenneth and his coterie of solemn priests walked the length of the humble horde, the pike blocks kneeling in ranks a hundred wide, six deep to be blessed. Men who had been cursing and wheeching carelessly in the night, hunting out the oblivion of women and drink in the baggage camp, now faced the cold silver of the day, shivering and crossing themselves as they begged forgiveness, knowing there was no time for everyone to take the abbot’s pyx.

The wee Abbot would be less even-handed with the wafer, Hal thought, if he knew that Wallace would burn him out in an eyeblink to get at his sanctuary sparrow once this bloody affair was concluded satisfactorily. A Wallace, buoyed by such a victory, would want to get at the truth of why a master mason was murdered – and whether a Bruce or a Comyn had done it. That knowledge would be a weapon of considerable sharpness.

The last censer swung away in a trail of dissipating smoke and Hal got to his feet and faced his father.

‘You should not be here,’ he said accusingly, raking the coals of the argument that had heated them both the previous night. ‘I left you safe, harvesting in Herdmanston.’

His father squinted a glare back at him, his iron-grey hair wisping in the breeze. Sir John Sientcler – The Auld Sire of Herdmanston, they called him, and he had been the capstone of that place for longer than the world itself, or so it seemed to Hal.

‘We ploughed that rigg last night,’ he growled back. ‘For my part, I thought you would be back long since. I sent ye to Douglas a terce of months ago an’ now find ye gallivantin’ about with rebels and another man’s wife.’

‘Ye … I …’

His father chuckled and laid a steel hand on Hal’s forearm.

‘Do not gawp like a raw orb,’ he chided gently. ‘We have shouted at yin another and there is an end to it, for this cannot now be undone.’

Which was a truth Hal did not care for, since it wrapped himself, his father and his men in the coils of that Trojan serpent. The Auld Templar, back at Roslin to see to his great-grandweans, had told Hal’s father what his son was about. Worse than that and unable to thole not being a part of any strike against the English, he had sent Roslin men to join Wallace – and stayed at home himself.

That last scorched Hal with a banked fire of fury. Stayed in Roslin and sent his steward – and the Auld Sire of Herdmanston. Who was no younger, Hal thought savagely, but a sight more honourable, so that he would not wriggle his way out of it with pleadings of old age, or that he was the only one to look to Herdmanston’s safety.

‘I have no fine warhorse and so cannot ride like a nobile this day,’ his father declared suddenly, bland as a wimple.

‘Balius is not mine. He is the Earl of Buchan’s and I am charged with taking him back, hale and hearty,’ Hal retorted, seeing the sly look the old man shot him. His father stroked his ragged beard and nodded.

‘Aye, aye, so I heard. Stallion and mare both back to the Comyn – the young Bruce is feeling generous. Pity, though, for I would have liked to have ridden as a knight proper in a great battle, just the yin time.’

‘It is a young man’s sport,’ Hal said, ignoring the wistful longing. Concern made him brutal. ‘That will be why the Auld Templar bided at home and sent his steward in his place. Sense would tell ye that is where you should be. You will note also the absence of a single chiel belonging to the Earl of Buchan, who still sits on his fence – or to Bruce, who is supposed to be on the English side. Save for us, who are in the wrong God-damned place.’

‘Weesht,’ he father chided softly. ‘The Auld Templar bides in Roslin because he cannot be seen involvin’ the Order in this stushie. And yourself is free to go – only I am sent to fight in this affair.’

He glanced at the outraged face of his son, already gasping out protest about how he was unable to leave his own da to certain death.

‘Certain death, is it?’ answered his father, cocking an eyebrow. ‘Bigod, ye set little store by my abilities these days. Besides – there was never a thought about yer auld faither when you were clatterin’ about with a coontess and a mystery. Ye have contrived to tangle yerself in the doings of Bruce, the Balliol and Comyn an’ this Wallace chiel. As if there was nothing left for you at home but a wee bit stane cross.’

Then his father relaxed and paced a little.

‘I ken why ye do it, boy,’ he said more softly and shook his head. ‘I miss them too. Grief is right and proper but what you are doing is … unhealthy.’

He stopped. Hal had nothing he could say that would not bring argument and anger, so he stayed silent – in the core of him he felt shame at what he had abandoned for grief and a sense that, like some chill cloud, it was lifting off him. His father waved a metal hand into his silence.

‘There’s sense in silence. No point in blowing away like a steamy pot,’ he said. ‘I have got myself dressed in all this iron at the behest of our liege lord, who seems determined to put Sientclers in harm’s way, God bless the silly auld fool. So I have come here to this field to dance, not hold a rush light on the side. I do not have a warhorse, but I will have a wee wheen of Roslin pike to order so it is not all bad. What we should be discussing is this mystery of the Savoyard and who you should be unravellin’ it to.’

‘Wallace …’ Hal said uncertainly and his father nodded, pursing lips so that his moustache ends stuck out like icicles.

‘He has asked you to look at it, certes. But a Bruce or a Comyn is involved in it, for sure … so trust nobody.’

He looked at his son steadily, his eyes firm in the middle of their pouched flesh.

‘Tak’ tent – trust no man. Not even the Auld Templar.’

‘What does that mean?’ Hal demanded and his father rolled his eyes and flung his hands up.

‘Christ’s Balls – may God forgive me – do ye listen or not? Trust no man – Sir William asks me a deal about this affair for a casual aside. A man has been red murdered already and whoever did it is no chivalrous knight. I ken Sir William is our kin in Roslin, but he is sleekit in this, so – trust no man.’

He looked at his son, a hard look filled with a desperation that stitched Hal’s arguments behind his lips.

‘Whoever did such a kill will come at you sideways, like a cock fighting on a dungheap,’ his father went on bleakly. ‘Even from the dark.’

He clasped his son by both forearms and drew him into a sudden, swift embrace, the maille of his shoulder cold, the aillette with its shivering cross rasping on Hal’s cheek. Then, just as suddenly, he stepped back, almost thrusting Hal away from him.

‘There,’ he declared huskily. ‘I will see you on the far side of this affair.’

Hal stared, wanting to speak, dumbed and numbed. He watched the armoured figure stump away into the throng, felt a presence on his shoulder and turned into Sim’s big squint.

‘Is Sir John fechtin’ then?’ he demanded and Hal could only nod. Sim shook his head.

‘Silly auld fool,’ he declared, then added hastily. ‘No slight intended.’

‘None ta’en,’ Hal answered, finding his voice. Then, more firmly, he added, ‘He will be fine, for we will be guarding his back. Seek young John Fenton, the steward of Roslin – that’s where father is, and so we will be.’

‘Good enough,’ Sim declared, glad to have some sort of plan for the day. Then he jerked a grimy thumb at lurking figures behind him; Hal realised, slowly, that they were Tod’s Wattie, Bangtail Hob and the rest, their faces shifty and eyes lowered. His heart sank.

‘Ye let the Savoyard get away,’ he said softly.

‘Aye and no,’ Tod’s Wattie began and Bangtail shushed him, stepping forward.

‘The Abbot came this morn,’ he said, ‘to tell us that a man arrived in the night and put the fear of God and the De’il both into the Savoyard. This stranger never got near our man, the Abbot says, but the Savoyard took fright and went out the infirmary drain.’

‘The what?’

Tod’s Wattie nodded, his eyes bright with the terror of it.

‘Aye. Show’s how desperate the chiel was. The spital drain, man …’

He left the rest unsaid and everyone regarded the horror for a silent moment. The infirmary drain was where every plague, every foulness from the sick lurked. For a man to risk himself to that, plootering like a humfy-backit rat through a slurry of ague, plague and worse …

‘Who arrived in the night?’ Hal demanded, suddenly remembering Bangtail’s words. Bangtail twisted his hands and cursed.

‘I saw him,’ he declared in a pained voice. ‘But ye said to keep folk from leaving, not to stop them getting in. If I had known who it was …’

‘Malise,’ Tod’s Wattie said, his voice like two turning querns. ‘Malise Bellejambe, who pizened the dugs. He is in there now, claimin’ the same sanctuary from us that the Savoyard did, for he kens what will happen whin I get my fists on him.’

‘I have sent men to find which way the Savoyard went,’ Sim added and Hal nodded slowly. Malise was on the trail of the Savoyard, which meant Buchan and the Comyn were involved.

Nothing more to be done with it on this, of all days. On the other side of it, God willing, he could start thinking matters through again.

Cressingham was a ranting, red-faced roarer, which did no good to his dignity with the troops he was supposed to be leading, Addaf thought. Mind you, the man is after having some reason.

The reason trailed behind him, coming back over the brig they had just crossed, led by the fat man bouncing badly on the back of his prancer of a horse so that the swans on his belly jumped.

‘I am thinking folk do not know their own minds, mark you,’ Heydin Captain declared, able to be loud and sour in Welsh, as they crowded back across the brig and sorted themselves out. Addaf saw the long-faced lord, Thweng, turn his mournful hound gaze back to where the Fore Battle straggled.

Cressingham scrambled off his horse and, already stiff and sore, stumped furiously up to the knot of men surrounding the magnificently accoutred Earl of Surrey, who stood deep in conversation with two men. One was the Scots lord, Lundie, the other was Brother Jacobus, his face quivering with outrage and white against his black robes.

‘He dismissed us, my lord. As if we were children. Said he had not come here to submit and would prove as much in our beards.’

Men growled and Lundie waved a dismissive hand.

‘Aye, Wallace has a way of speaking, has he not?’ he said, mockingly. ‘But Moray’s is the voice to listen to, my lords, and he will have some plan to take advantage of having to cross this narrow brig, my lord. You have seen how it is -two riders side by side can scarce find room to move. There is a ford further up. Give me some men and I will flank him – it will take me the best part of this day and you can cross in perfect safety tomorrow.’

‘Tomorrow,’ bellowed Cressingham, forcing everyone to turn and look at him. The Earl of Surrey saw the red pig-faced scowl of him and sighed.

‘Treasurer,’ he said mildly. ‘You have something to add?’

‘Add? Add?’ Cressingham spluttered and his mouth worked, loose and wet for a moment. Then he sucked in breath.

‘Aye, I have something to add,’ he growled and pointed a shaking, gauntleted hand at De Warenne. ‘Why in the name of God and all his Saints am I marching back and forth across this bloody bridge? Answer me that, eh?’

The Earl of Surrey felt men stir at the insulting way Cressingham was speaking, but quelled his own anger; besides, he felt tired and his belly griped. Deus juva me, he thought as the pain lanced him, even the crowfoot powder no longer works.

‘Because, Treasurer,’ he answered slowly, ‘I did not order any movement.’

Cressingham blinked and his face turned an unhealthy colour of purple. He will explode like a quince in a metal fist, De Warenne thought.

‘I ordered it,’ the Treasurer exclaimed, his voice so high it was nearly a squeak. ‘I ordered it.’

‘Do you command here?’ De Warenne responded mildly.

‘I do when you are still asleep and half the day of battle wasted,’ roared Cressingham and folk started make little protesting noises now.

‘Have a care,’ someone muttered.

‘Indeed,’ De Warenne agreed sternly. ‘I will have my due from you, Treasurer. Remember your place.’

Cressingham thrust his great broad face into the Earl of Surrey’s indignantly quivering beard. Sweat sheened the Treasurer’s cheeks and trembled in drips along jowls the colour of plums.

‘My place,’ he snarled, ‘is to make sure you do the king’s bidding. My place is to get this army, gathered at great expense, to do the job it is supposed to and destroy this rabble of Scots rebels. My place is to explain to the king why the Earl of Surrey seems determined not to do this without spending the entire Exchequer. If you wish to stand in my place before the king himself, my lord earl, please feel free.’

He stopped, breathing like a mating bull; the coterie waited, watching the Earl of Surrey, who closed his eyes briefly against the hot wind of Cressingham’s breathing.

He wanted to slap this fat upstart down with a cutting phrase, but he knew the Treasurer was correct; the king wanted this business done as quickly and cheaply as possible and the last thing De Warenne wanted was to have to face the towering menace of Edward Plantagenet with a monstrous bill in one hand and failure in the other. He gathered the shreds of himself and turned to the Scot.

‘As you see, Sir Richard,’ he declared, mild as milk, ‘the ink-fingered clerks will not permit delay. I am afraid your war-winning strategy will have to be foregone in favour of Cressingham’s crushing delivery.’

Then he turned to Cressingham, his poached-egg eyes wide, white brows raising, as if surprised that the scowling Treasurer was still present. He waved a languid hand.

‘You may proceed across the river.’

***

Hal stood to the left of the little pike square, the front ranks heavy with padded, studded gambesons and iron-rimmed hats, the back ones filled with bare heads and bare feet, trembling, grim men in brown and grey.

A hundred paces in front of him was a long, thin scattering of bowmen, right along the front to right and left and for all Hal knew there were some four hundred of them, it looked like a long thread of nothing at all.

There were shouts; a horseman thundered past and sprayed up clods so that everyone cursed him. He waved gaily and shouted back, but it was whipped away by the wind and he disappeared, waving his sword.

‘Bull-horned, belli-hoolin’ arse,’ Sim growled, but the rider was simply the herald for Wallace and Moray. Hal saw the cavalcade, the blue, white-crossed banners and then the great red and gold lion rampant, with Moray’s white stars on blue flapping beside it. Wallace, Hal saw, wore a knight’s harness and a jupon, red with a white lion on it. He also rode a warhorse that Hal knew well and he gaped; Sim let out a burst of laughter.

‘Holy Christ in Heaven, the Coontess has lent Wallace your big stot.’

It was Balius, sheened and arch-necked, curveting and cantering along the line of roaring squares as Wallace yelled at them. When he came level, Hal heard what he said clearly, a shifting note as the powerful figure, sword raised aloft, rode along the line, followed by a grinning Moray and the scattered band of banner-carriers.

Tailed dogs.

As a rousing speech, Hal thought, it probably fell far short of what the chroniclers wanted and they would lie about it later. Six thousand waited to be lifted and not more than a hundred would hear some rousing speech on liberty, with no time to repeat it, ad infinitum.

‘Tailed dogs’ repeated all the way along the long line did it this time: the ragged, ill-armoured horde, half of them shivering with fear and fevers, most of them bare-legged and bare-arsed because disease poured their insides down their thighs, flung their arms in the air and roared back at him.

‘Tailed dogs,’ they bellowed back with delight, the accepted way to insult an Englishman and popularly believed as God’s just punishment on that race for their part in the murder of Saint Thomas a-Becket; the Scots taunt never failed to arouse the English to red-necked rage.

Hal leaned out to look down the bristle of cheering pikes to where his father stood, leaning hip-shot on a Jeddart staff which had the engrailed blue cross fluttering from a pennon. He had his old battered shield slung half on his back, the cock rampant of the Sientclers faded and scarred on it – that device was older even than the shivering cross.

Beside him stood Tod’s Wattie, offered up as standard-bearer in a cunning ploy by Hal to get him close enough, so that he now struggled with both hands to control the great wind-whipped square of blue slashed with the white cross of St Andrew. He had that task and the surreptitious protection of the Auld Sire to handle and he did not know which one was the more troublesome.

The great cross reminded Hal of the one he wore and he looked at the two white strips, hastily tacked over his heart in the X of St Andrew. A woman with red cheeks and worn fingers had done it when he had taken Will Elliot to Isabel in the baggage camp, finding her with the woman and the Dog Boy, moving among those already sick.

‘This is Red Jeannie,’ Isabel declared and the bare-legged woman had bobbed briefly and then frowned.

‘Ye have no favour,’ she said and proceeded to tack the strips on Hal’s gambeson while he told Isabel that Will Elliot was here to guard her and the Dog Boy should the day go against them.

‘He will keep ye safe,’ he added. ‘Mind also you have that Templar flag, so wave that if it comes to the bit.’

She nodded, unable to speak, aware of the woman, tongue between her teeth, stitching with quick, expert movements while Hal looked over her head into Isabel’s eyes. She wanted to tell him how sorry she was, that it was all her fault that he was here, trapped in a battle he did not want, but the words would not come.

‘I …’ he said and a horn blared.

‘You had best away,’ Isabel said awkwardly and Red Jeannie finished, stuck the needle in the collar of her dress and beamed her windchaped face up into Hal’s own.

‘There, done and done,’ she said. ‘If ye see a big red-haired Selkirk man with a bow, his name is Erchie of Logy and ye mun give him this.’

She took Hal’s beard and pulled him down to her lips so hard their teeth clicked. He tasted onion and then she released him as fiercely as she had grabbed him.

‘God keep him safe,’ she added and started to cry. ‘Christ be praised.’

‘For ever and ever,’ Hal answered numbly, then felt Isabel close to him, smelled the sweat-musk of her, a scent that ripped lust and longing through him, so that he reeled with it.

‘Go with God, Hal of Herdmanston,’ she said and kissed him, full and soft on the lips. Then she stepped back and put her arm round the weeping Jeannie, leading her into the carts and sumpter wagons and the wail of women.

The kiss was with him now, so that he touched his gauntlet to his mouth.

‘Here they come again,’ Sim declared and Hal looked down the long, slope, sliced by the causeway that led to the brig. On it, small figures moved slowly, jostling forward, spilling out like water from a pipe and filtering up.

‘Same as afore,’ Sim said. ‘It seems they are awfy fond with walking back and forth across the brig.’