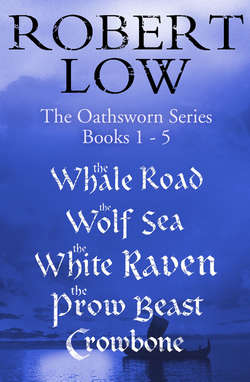

Читать книгу The Oathsworn Series Books 1 to 5 - Robert Low - Страница 34

ONE

ОглавлениеMIKLAGARD, the Great City, AD 965

His eyes flicked to the bundle in my hand, then settled on my gape-mouthed face like flies on blood. They were clouded to the colour of flint, those eyes, and his snake moustaches writhed as he sneered at me, the blow I had given him having done nothing except annoy him.

‘Big mistake,’ he snarled in bad Greek and moved up the alley towards me, hauling a seax the length of my forearm out from under his cloak.

I hefted the wrapped sabre, swung it and revealed how clumsy the weapon was in that single moment. He grinned; I backed up, slithering through black-rotted rubbish, wishing I had just gone my way and ignored him.

He was quick, too, darting in fast and low, but I had been watching his feet not his eyes and swung the bundle so that it smacked him sideways into the wall. I followed it with a big overarm hack, but missed. The bundled sword cut through the wrappings and struck sparks from the wall.

Showered with brick and plaster chips, he was alarmed, both at the near miss and the fact that there was now a sharp edge involved. I saw it in his eyes.

‘Didn’t expect this, did you?’ I taunted as we shifted and eyed each other. ‘Tell you what – you tell me why you are following me all over Miklagard and I will let you go.’

He blinked astonishment, then chuckled like a wolf who has found a crippled chicken. ‘You’ll let me go? I don’t think you realise who you are facing, swina fretr. I am a Falstermann and not one to take such insults from a boy.’

So I had been clever about him being a Dane, I thought. It was a pity I had not been so clever about taking him on. His feet shifted and I had been watching for that, so that when he swung I caught the seax on the shredded bundle, wincing at the blow. I turned my wrist to try and tangle his blade in cloth and almost managed to twist the seax free of his grasp. He was too old a hand for that, though, and I was too clumsy with the sword wrapped as it was.

Worse than that – even now I sweat with the shame of it – his oarmate came up behind me, elbowed the breath out of me and slammed me to the clotted filth of the alley. Then he plucked the wool-coddled sword from my fluttering hands, easy as lifting an egg from a nest and, dimly, I realised that’s what they had wanted all along. I was gasping and boking too much to do anything about it.

‘Time to row hard for it,’ this unseen one growled and I heard his steps squelching through the alley filth.

I was sure death had not been in the plan of this, but the man from Falster had blood in his eye and I had rain in mine, blurring the world. The cliff walls of the alley stretched up to frame a patch of indifferent grey sky and it came to me then that this would be the last sight I would see.

I did not want to die in a filthy alley of the Great City with the rain in my eyes. Not that last, especially, for the vision of the first man – the boy – I had killed came back to me, lying on a heath with his bloodless face and his eyes open and startled under little pools of rainwater.

The Falstermann loomed over me, breathing hard, the seax reversed for a downward thrust straight at my belt loop, rain pearling mistily on the pitted steel, sliding carelessly along the edge …

The rain, says Sighvat, will tell you all about a place if you know how to read it. The rain in a Norway pine wood is good enough to wash your hair in but, if a city is really old, it drips from the eaves with the grue of ages, black as pitch, harsh as a curse.

Miklagard, the Great City, was ancient and her pools and gutters spat and hissed like an evil snake. Even the sea here was corroded, heaving in slow, fat swells, black and slick and greasy as a wet hog’s back, glittering with scum and studded with flotsam.

I did not even want to be in this city and the gawping wonder of it had long since palled. Stumbling from the ruined dream of Attila’s silver hoard, those of the Oathsworn who survived the Grass Sea of the steppe had washed up here, after a Greek captain had been persuaded to take us. Since then, my great plan had been to load and unload cargo on the docks, husband what little real money we had, waiting for the rest of the Oathsworn to join us from far-off Holmgard and make a crew worth hiring for something better.

At the end of it all, distant as a pale horizon, was a new ship and a chance to go back for all that silver, a thought we hugged for warmth as winter closed in on Miklagard, drenching the Navel of the World in misery.

That black rain should have been warning enough, but the day the runesword was stolen from me I was wet and arrogant and angry at being followed all along in the lee of Severus’s dripping walls by someone who was either bad at it, or did not care if he was seen. Either way, it was not a little insulting.

On a clear day in Constantinople you could almost see Galata across the Horn. That day I could hardly see the man following me in the polished bronze tray I held up and pretended to study, as if I would buy it.

A face twisted and writhed in the beaten, rain-leprous surface, a stranger with a long chin, a thin, straggled beard, a moustache still a shadow and long, brown-red-coloured hair that hung in braids round the brow, some of them tied back to keep the hair from the blue eyes. My face. Beyond it, trembling and distorted, was my shadower.

‘What do you see?’ demanded the surly Greek owner of the tray and all its cousins laid out on a worn strip of carpet under an awning, heavy with damp. ‘A lover, perhaps?’

‘Tell you what I don’t see,’ I said with as sweet a smile as I could muster, ‘you gleidr gaugbrojotr. I don’t see a sale.’

He snorted and snatched the tray from me, his sallow face flushed where it wasn’t covered with perfumed beard. ‘In that case, fix your hair somewhere else, meyla,’ he snapped, which I had to admit was a good reply, since it let me know that he understood Norse and that I had called him a bowlegged grave-robber. He had called me little girl in return. From this sort of experience, I learned that the merchants of Miklagard were as sharp as their manners and beards were oiled.

I smiled sweetly at him and strolled off. I had learned what I needed: the bronze tray had revealed, beyond my face and watching me, the same man I had seen three different times before, following me through the city.

I wondered what to do, clutching the wrapped bundle of the runesword and chewing scripilita, the chickpea-flour bread, thin and crusty on top, glistening with oil on the bottom, wrapped in broadleaves and – wonder of wonders – thickly peppered. This treat, which was never seen further north than Novgorod, was so expensive beyond the Great City, thanks to the pepper, that it would have been cheaper to dust it with gold. The seductive taste of it and the cold was what made me blind and stupid, I swear.

The street led to a little square where the windows were already comfort-yellow with light as the early winter dark closed in. I had, even in so short a time, lost the wonder that had once locked my feet to the street at the sight of houses put one on top of the other and had eyes only for my tracker. I paused at a knife-grinder’s squeaking wheel, glanced back; the man was still there.

He was from the North, for sure, for he was taller than any others and clean-shaven but for the long snake moustaches, a Svear fashion that was much fancied by dandies then. He had long hair, too, which he had failed to hide well under a leather cap, and wore a cloak, under which could lurk anything sharp.

I moved on, past a stand where a woman sold chickpea flour and dried figs. Next to her, a man in a sleeveless fleece sold cheeses out of a single basket and, leaning against the wall and trying not to let their teeth chatter in the cold, a pair of girls tried to look alluring and show breasts that were red-blue.

The Great City is a miserable place in winter. It has the Sea of Darkness at its back and behind that the Grass Sea of the Rus; and it is a place of gloom and penetrating damp. There may be a flicker of late summer and even pleasant days at the start of the year, but you cannot count on sun, only rain, between the last days of harvest and the first ones of the festival of Ostara, which the Miklagard priests call Paschal.

‘Come and warm me,’ one of the girls said. ‘I can teach you how to make a beast with two backs if you do.’

I knew that trick and moved on, trying to keep the man in sight by turning and exchanging some good insults, then bumped into a carder of wool coming up the other way, demanding that people buy his mattress stuffings or risk freezing their babies by their carelessness.

The street slithered wetly down to the docks, grew crowded, sprouted alleyways and spawned people: bakers, sellers of honey, vendors of tanned leather for making cords, those selling the skins of small animals. This was not the fashionable end of Miklagard, this collection of lumpen faces and beggar hands. They were the halt, the lame and the poxed, most of whom would die in the cold of this winter unless they got lucky.

It was already cold in the Great City, cold enough to numb my senses into thinking to find out who this man was and why he followed me.

So I slid up one of the alleys and hefted the bundle that was the runesword, it being the only weapon I had besides an eating knife. My plan was to tap him with the cushioned blade of it as he passed, drag him in the alley and then threaten him with the sharp end until he babbled all he knew.

He duly obliged, even pausing at the mouth of the alley, having lost me and wondering where I had gone. If I had stayed in the shadows, I would have shaken him off, for sure – but I stepped out and rapped him hard on the head.

There was a clatter; he staggered and yelled: ‘Oskilgetinn!’, which at least let me know I had been right about him being from the North – though you could tell by his roar that it meant ‘bastard’ even if you couldn’t speak any Norse. The curse let me know he was at least prime-signed, if not fully baptised, since only Christ-followers worried about children born out of wedlock. A Dane, then, and one of King Harald Bluetooth’s new Christ-converts. I did not like what that promised.

The third thing I found out was that his cap was a metal helmet covered in leather and most of the blow had been taken on it. The fourth was that he was from Falster and I had made him angry.

That was what I learned. I missed many things, but the worst miss of all was his oarmate, coming up behind me and leaving me gasping in the alley, the sword gone and pearled rain dripping off the Falstermann’s blade, raised to finish me.

‘Starkad won’t be pleased,’ I gasped and the big Dane hesitated for long enough to let me know I had it right and he was a chosen man of an old enemy we had blooded before. Then I lashed out with my right leg, aiming for his groin, but he was too clever for that and whacked my knee hard with the flat of the blade, which he then pointed at me.

He wanted to kill me so bad he could taste it, but we both knew Starkad wanted me alive. He would want to gloat and wave the stolen runesword in my face, the one now long vanished up the alley. The Falstermann, wanting to be away himself, started to say a final farewell, which would have included how lucky I was and that the next time we met he would gut me like a fish.

Except that all that came out was ‘guh-guh-guh’ because a knife hilt had somehow appeared beneath his right ear and the blade was all the way into his throat.

A hand pulled it out as casually as if it were plucking a thorn and the hiss of escaping blood was loud, the splatter of it everywhere as the Dane collapsed like an empty waterskin.

Blinking, I looked up to what had replaced him against the yellow lantern glow of the window lights beyond the alley: a big man, shave-headed save for two silver-banded braids over each ear, wearing the checked breeks of the Irish and a tunic and cloak that was Greek. He also had a long knife and a tattooed whorl between his eyes, which I knew was the Ægishjalm, the Helm of Awe, a runesign supposed to send your enemies away screaming in terror with the right words spoken. I wished he would turn it off, for it was working well on me.

‘I heard him call you pig fart,’ he said in good East Norse, his eyes and teeth bright in the alley’s twilight. ‘So I reasoned he bore you no goodwill. And, since you are Orm the Trader, who has a crew and no ship, and I am Radoslav Schchuka, who has a ship and no crew, I was thinking my need for you was greater than his.’

He helped me up with a wrist-to-wrist grip and I saw that his bared forearm had several thick-welted white scars. I looked at the dead Dane as this Radoslav bent and rifled his purse, finding a few coins, which he took, along with the seax. Then it came to me that I should be dead in the alley and my legs trembled, so that I had to hold on to the wall. I looked up to see the big man – a Slav, for sure – cutting his own arm with the seax and realised the significance of the scars.

He saw my look and showed me his teeth in a sharp grin. ‘One for every man you kill. It is the mark of my clan, where I come from,’ he explained, then helped me roll the Dane in his cloak and back into the shadows of the alley. I was shaking now, but not at my narrow escape – it had come to me that the Dane would have gone his way and left me lying in the muck, alive – but at what had been lost. I could have wept for the shame of losing it, too.

‘Who were they?’ asked my rescuer, binding up his new scar.

I hesitated; but since he had painted the wall with a man’s blood, I thought it right that he knew. ‘A chosen warrior of one Starkad, who is King Harald Bluetooth’s man and anxious that he get something from me.’

For Choniates, I suddenly thought, the Greek merchant who had coveted that runed sword when he’d seen it. It was clear the Greek had sent Starkad to get it and would be unhappy about the death. The Great City had laws, which they took seriously, and a dead Dane in an alley could be tracked back to Starkad and then to Choniates.

Radoslav shrugged and grinned as we checked no one could see us, then left the alley, striding casually along as if we were old friends heading for a drink-shop. My legs shook, which made the mummery difficult.

‘You can judge a man by his enemies, my father always said,’ Radoslav offered cheerfully, ‘and so you are a great man for one so young. King Harald Bluetooth of the Danes, no less.’

‘And young Prince Yaropolk of the Rus also,’ I added grimly to see his reaction, since he was from that part of the world. Beyond a widening of his eyes at this mention of the Rus King’s eldest son there was silence, which lasted for a few footsteps, long enough for my racing heart to settle.

I was trying desperately to think, panicked at what had been lost, but I kept seeing that little knife come out of the Dane’s neck under his ear and the blood hiss like spray under a keel. Someone who could do that to a man is someone you must walk cautiously alongside.

‘What did he steal?’ Radoslav asked suddenly, the rain glistening on his face, turning it to a mask of planes and shadows.

What did he steal? A good question and, in the end, I answered it truthfully.

‘The rune serpent,’ I told him. ‘The roofbeam of our world.’

I brought him to our hov in a ruined warehouse by the docks, as you would a guest who has saved your life, but I did this Radoslav no favours. Sighvat and Kvasir and Short Eldgrim and the rest of the Oathsworn were huddled damply round a badly smoking brazier, talking about this and that and, always, about Orm’s plan to get them back to sea in a fine ship, so that they could be proper men again.

Except Orm didn’t have a plan. I had used up all my plans getting the dozen of us away from the ruin of Attila’s howe months before, paying the steppe tribes with what little I had ripped from that flooding burial mound – and had nearly drowned to get, the weight of it stuffed in my boots almost dragging me down.

I could not get rid of the Oathsworn after we had all been dumped on the quayside. Like a pack of bewildered dogs they had looked to me. Me. Young enough for any to call me son and yet they called me ‘jarl’ instead and boasted to any they met that Orm was the deepest thinker they had ever shared an ale horn with, even as I spun and hung my mouth open at the sheer size and wealth and wonder of the Great City of the Romans.

Here, the people ate free bread and spent their time howling at the chariot and horse races in the Hippodrome, fighting mad over their Blue or Green favourites and worse than any who went on a vik, so that city-wide riots were common.

The char-black scars from the previous year still marked where one had spread out, incited by opponents of Nikephoras Phocas, who ruled here. It had failed and no one knew who had fed the flames of it, though Leo Balantes was a name whispered here and there – but he and other faces were wisely absent from the Great City.

A black-hearted city right enough, which turned the slither from the gutters crow-dark so that we knew, even if the story of it curled on itself like a carved snake-knot, that cruelty squatted in Miklagard. Blood-feuds we knew well enough, but Miklagard’s treachery we did not understand any better than the city’s screaming passion for chariots and horses that raced instead of fought.

We were wide-eyed bairns on this new ship and had to learn how to sail it, fast. We learned that calling them Greek was an insult, since they considered themselves Romans, the only true ones left. But they all spoke and wrote in Greek and most of them knew only a little Latin – though that did not stop them muddying the waters of their tongue with it.

We learned that they lived in New Rome, not Constantinople, nor Miklagard, nor Omphalos, Navel of the World, nor the Great City. We learned that the Emperor was not an Emperor, he was the Basileus. Now and then he was the Basileus Autocrator.

We learned that they were civilised and we could not be trusted in a decent home, where we would either steal the silver or hump the daughters – or both – and leave dirty marks on the floors. We learned all this, not from kindly teachers, but from curled lips and scorn.

The slaves were better off than us, for they were fed and sheltered free, while we took miserable pay every day from a fat half-Greek, which would not let us afford either decent mead – even if we could find it here – or a decent hump. My stock of Atil’s silver was all but exhausted and still no plan had come to me yet and I wondered how long the Oathsworn would stomach this.

Singly and in pairs like half-ashamed conspirators all of them had approached me at one time or another since we had been here, all with the same question: what had I seen inside Attila’s howe?

I told them: a mountain of age-blackened silver and a gifthrone, where Einar the Black, who had led us all there, now sat for ever as the richest dead man in the world.

All of them had been there – though none but me inside it – yet none could find the way back to it, navigating themselves like a ship across the Grass Sea. I knew they also felt the fish-hook jerk of it, despite all that they had suffered, no matter that they had watched oarmates die there and had felt the dangerous, sick magic of that place for themselves.

Above all, they knew the curse that came from breaking the oath they had sworn to each other. Einar had broken it and they all saw what had become of that, so none slipped away in the night, abandoning his oarmates to follow the lure of silver. I was not sure whether this was from fear of the curse, or because they did not know the way, but they were Norsemen. They knew a mountain of riches lay out on the steppe and they knew it was cursed. The wrench between fear and silver-desire ate them, night and day.

Almost every night, in the quiet of that false hov, they wanted to look at the sword, that sinuous curve of sabre wrenched from Atil’s howe by my hand. A master smith had made that, a half-blood dwarf or a dragon-prince, surely no man. It could cut the steel of the anvil it was made on and was worked along the blade length with a rune serpent, a snake-knot whose meaning no one could quite unravel.

The Oathsworn came to marvel at that steel curve, the sheen of it – and the new runes I had carved into the wooden hilt. I had come late to the skill and needed help with them, but those were simple enough, so that any one of the Oathsworn could read them, even those who needed fingers to trace them and mumbled aloud.

Only I knew they marked the way back to Atil’s howe in the Grass Sea, sure as a chart.

A chart I had now managed to lose.

All of this swilled round in my head, dark as the water from Miklagard’s gutters, as I hunched through the rain towards our ratty warehouse hall, dragging the big Slav with me. The wind blasted and grumbled and, out across the black water, whitecaps danced like stars in a night sky.

‘You look like you woke up with the ugly one, having gone to bed with golden-haired Sif,’ Kvasir growled as I stumbled in, shaking rain off, slapping the piece of sacking that was my cloak and hood. His good eye was bright, the other white as a dead fish, with no pupil. He looked the big Slav up and down and said nothing.

‘Thor’s golden wife wouldn’t look at him,’ said a lilting voice. ‘Though half the Greek man-lover crews here would. Maybe that is the way ahead for us, eh, Orm?’

‘The way behind, you mean,’ jeered Finn Horsehead, jerking lewd hips and roaring at his own jest. Brother John’s look was withering and Finn subsided into mock humility, nudging his neighbour to make sure he had caught his fine wit.

‘Never be minding,’ Brother John went on, taking my elbow. ‘Come away here and sit you down. There’s a fine cauldron of … something … with vegetables in it that Sighvat lifted and Finn made with pigeons. And a griddle of flatbread. Enough for our guest, too.’

The men made room round the brazier and Brother John ushered us to a place, gave us bowls, bread and a wink. Radoslav looked at the food and it was clear a stew made of the Great City’s pigeons was not the finest meal he had eaten, nor – with the wind hissing through the warehouse, flaring the brazier embers – was this the best hall he had been in. But he grinned and chewed and gave every indication of being well treated. I took a bowl, but my mouth was full of ashes.

I introduced Radoslav. I told them why he was here and that what we had feared had happened – the rune-serpent sword was gone. The silence was crushing, broken only by the sigh of wind ruffling the curls on Brother John’s half-grown forehead. You could hear the sky of our world falling in that silence.

Brother John had been on the boat when we had boarded it on the Sea of Darkness. The Greek and his crew thought he was one of us, we thought he was one of them and neither found out until after we were ashore. We had taken to Brother John at once for that Loki trick and afterwards he had astounded us all by telling us he was a Christ priest.

Not one like Martin, the devious monk from Hammaburg, the one I should have killed when I had the chance. Brother John was from Dyfflin and an altogether different breed of horse. He did not shave his head in the middle like the usual priests, he shaved it at the front – when he could be bothered. ‘Like the druids did in times of old,’ he offered cheerfully when asked.

He did not wear robes either and he liked to drink and hump and fight, too, even though he was hardly the height of a pony’s arse. He was on his second attempt to get to Serkland, trying to reach his Christ’s holy city, having failed the first time and, as he said himself, sore in need of salvation.

I was sore in need of the same and dare not look anyone in the eye.

‘Starkad,’ muttered Kvasir. ‘Fuck his mother.’ His head drooped. There were grunts and growls and sniffs, but it was a perfect summing up and the worst sound of all was the despairing silence that followed.

Sighvat broke it. ‘We have to get it back,’ he declared and Kvasir snorted derisively at this self-evident truth.

‘I will tear his head off and piss down his neck,’ growled Finn and I was not so sure that he was talking about Starkad and not me. Radoslav, food halfway to his mouth, had stopped chewing and looked from one to the other, only now realising that something truly valuable had been taken.

‘Starkad,’ said Finn in a voice like a turning quernstone. He stood and dragged the seax out, looking meaningfully at me. The others growled approval and their own hidden knives flashed.

Despair closed on me like dark wolves. ‘He works for the Greek, Choniates,’ I said.

‘Aye, right enough, we saw him there,’ agreed Sighvat and if there is a colour blacker than his voice was then, the gods have not seen fit to show us it yet.

Finn blinked, for he knew what that meant. Choniates had power and money and that permitted him armed guards and the law. We were Norse, with all that stood for in the Great City. Bitter experience had taught the people of Miklagard just what the Norse did in their halls during the long, dark winters, especially men with no wives to stay their hands. The Great City’s tabernae and streets did not want feasting Northmen getting drunk and killing each other – or worse, the good citizens – so the city had made a law of it, which they called the Svear Law. We could carry no weapons and would be arrested for the ones gleaming in the firelight here. We had only a limited time in the Great City and soon we would be rounded up and pitched out beyond the frontier if we did not get a ship in time to leave ourselves.

Finn wolfed it all out in a great howl of frustration that bounced echoes round the warehouse and started up local dogs to reply, his head thrown back and the cords of his neck standing out like ship’s cables. But even he knew we would not profit from charging up to Choniates’ marbled hov, kicking in the door and dangling him by the heel until he coughed up the runesword. All we would get was dead.

‘Choniates is a merchant of some respectability,’ Radoslav said, quiet and cautious about the smouldering rage round him. ‘Are you sure he has done this thing? What is this rune serpent anyway?’

Glares answered that. Choniates had it, for sure. Architos Choniates had seen the sword weeks ago and I had been expecting something since then – only to ease my guard at the last and lose it.

When we had first staggered on to the docks of the Great City, it was made clear we would remain unmolested provided we could pay our way. I had half a boot of coins and trinkets left, the last cull from Atil’s howe, but they were not seen as currency, so had to be sold for their worth in real silver – and Architos Choniates was the name that kept surfacing like a turd in a drain.

It took two days to arrange, because the likes of Choniates wasn’t someone you could walk up to, a ragged-breeks boy like me. He had no shopfront, but was known as a linaropuli, a cloth merchant – which was like calling Thor a bit of a hammer-thrower.

Choniates dealt in everything, but cloth especially and silk in particular, though it was well known that he hated the Christ church’s monopoly on making that fabric. Brother John found a tapetas, a rug dealer, who knew a friend who knew Choniates’ chief spadone and, two days later, this one turned up in the Dolphin.

Outside it, to be exact, for he wouldn’t set foot inside such a place, despite the rain. He sat in a hired carrying-chair, surrounded by hired men from the guild of the racing Blues, wearing their neckcloths to prove it. They were all scowling toughs sporting the latest in Great City fashion: tunics cinched tight at the waist and stiffened at the shoulders to make them look muscle-wide. They had decorated trousers and boots and their hair was cut right back on the front and grown long and tangled behind.

It was all meant to make them look like some steppe tribe come to town, but when one came into the Dolphin and asked for Orm the Trader, he was almost weeping with rage and frustration at the hoots and jeers of men who had fought the real thing.

We all went out, for the others were anxious to see what a spadone, a man with no balls, looked like, but were in for a disappointment, since he looked like us, only cleaner and better groomed. He was swathed in a thick cloak, drawn up over his head so that he looked like an old Roman statue, and he inclined his head graciously in the direction of the gawping mob of pirates who confronted him.

‘Greetings from Architos Choniates,’ he said in Greek. ‘My name is Niketas. My master bids me tell you that he will see you tomorrow. Someone will come and bring you to him.’

He paused, looking round at us all. I had followed his talk well enough, as had Brother John, but the others knew just enough Greek to get their faces slapped and order another drink, so they were engaged in peering at him. Finn Horsehead was practically on his knees, trying to squint into the carrying-chair, and I could see he was set on lifting clothing to get a better look at what wasn’t there.

‘We will be ready,’ I said, cuffing Finn’s ear. ‘Convey my thanks to your master.’

He nodded at me politely, then hesitated. Finn, scowling and rubbing his ear, was glaring at one of the smirking thugs who formed the bodyguard.

‘You may bring no more than three others,’ Niketas said as they left. ‘Suitably comported.’

‘“Suitably comported”,’ chuckled Brother John as we watched them go. ‘How are we to do that at all?’

In the end, I decided Sighvat and Brother John were best and left it at that, ignoring Finn’s demands to be included.

‘He may just decide to lift it,’ he argued. ‘Or send men to ambush you on the way.’

‘He is a merchant,’ I said wearily. ‘He depends on his reputation. He won’t get far by waving a blade and robbing everyone.’

How wrong that turned out to be.

The next day we were escorted by another of Choniates’ household to the expensive end of the city and were greeted by Niketas in the immaculate atrium of a large house. He eyed us with one brow raised, taking in our stained, worn clothes, flapping soles and long beards and hair. I felt like a grease stain in this marbled hov.

Sighvat, who took considerable pride in his appearance – we all did, for we were Norsemen and, compared to others in the world, a byword for cleanliness – scowled back at Niketas and hissed, ‘If you had balls left, I would tear them off.’

Niketas, who must have heard it all before, simply bowed politely and then left. It may be that Choniates was then busy for two hours, or that Niketas was vengeful.

But it gave us a chance to watch and learn in a part of the city where life seemed careless. People came and went in Choniates’ lavish hall with no apparent purpose other than to lean against polished balustrades and laugh and talk and bask in the perfect sun of their lives, warmed, on this chilly, damp day, by heat that came under the floor.

They drank wine from bowls, spilled it, laughingly daring, as an offering to older gods and chided each other for getting it on their expensive sleeves, patting their clothes with sticky-ringed hands. Sighvat and I spent some time wondering if you could get those sticky rings off without cutting their fingers and even more wondering how the heat came up from the floor without the place burning down.

Choniates, when we were finally ushered into his presence, was tall, dressed in gold and white and with perfect silver hair. He conducted affairs in a chair at first, surrounded by men who softened his face with hot cloths, slathered him with cream and then, to our amazement, started painting it with cosmetics, like a woman. They even used brown ash on his eyelids.

He was offhand, dismissive – I was a badly dressed varangii boy, after all, clutching a bundle wrapped in rags, accompanied by a big, hairy, fox-faced man and a tiny, bead-eyed heretic monk who spoke Latin and Greek with a thick accent.

After he had seen the coins, though, he grew thoughtful and that did not surprise me. They were Volsung-minted and the only ones in the world not in Atil’s dark tomb were the ones he turned over and over in his fat, manicured fingers. He knew their worth in silver – and, more than that, he knew what they meant and that the rumours about the Oathsworn were true.

He asked to see the sword and, made bold and anxious to please, I unwrapped that bundle and everything changed. He could scarcely bring himself to touch it, knew then who this Orm was and saw the beauty and the worth of that sabrecurve, even if he did not know what the runes meant, on hilt or blade.

‘Will you sell this, too?’ he asked and I shook my head and wrapped it up again. I saw in his eyes the look I was fast getting used to: the greed-sick, calculating stare of those wondering how to find out if the rumours of a marvellous silver hoard were true and, if so, where it was. The sword, as it was bundled up again, was like the dying sun to a flower as Choniates stood and watched it vanish into filthy wrappings. I knew then that showing it to him had been a mistake, that he would try something.

The barbers and prinkers were waved away; he offered wine and I accepted and sipped it – it was unwatered and I laughed aloud at his presumption. By the end of a long afternoon, Choniates reluctantly discovered that he would get no bargain for the coins, nor any clue as to other treasures.

He bought the coins and trinkets, paying some cash then, the bulk by promise – and extra for trying a cheap trick like getting me drunk.

‘That went well,’ beamed Brother John when we were out on the rain-glistening street.

‘Best we watch our backs,’ muttered Sighvat who had seen the same signs as I had.

Then, as we turned for a last look at the marble hov, we both saw Starkad, quiet and unfussed, hirpling through the gate like an old friend, not exactly fox-sleekit about it, but looking this way and that quickly, to see if he was observed. Even without the limp, which Einar had given him, both Sighvat and I knew this old enemy when we saw him – but, just then, the Watch tramped round a corner and we slid away before they spotted us and started asking awkward questions.

That had been weeks ago and Choniates, it had to be said, had been patient and cunning, waiting just long enough for us – me – to relax a little, to grow careless.

Oh, aye. We knew who had the runesword, right enough, but that only made things worse.

Finn grew redder and finally hacked the pigeon he had been plucking into bloody shreds and flying feathers until his rage went and he sat down with a thump. Radoslav, clearly impressed, picked some feathers from his own bowl and carried on eating slowly, spitting out the smaller bones. No one spoke and the gloom sidled up to the fire and curled there like a dog.

Brother John winked at me from that round face with its fringe of silly beard and jingled a handful of silver in one fist. ‘I have enough here for at least one mug of what passes for drink in the Dolphin,’ he announced. ‘To take away the taste of Finn’s stew.’

Finn scowled. ‘When you find more of that silver, you dwarf, perhaps we can afford better than those rats with wings that I catch. Get used to it. Unless we get that blade back, we will eat worse.’

Everyone chuckled, though the loss of the runesword drove the mirth from it. The pigeons in the city were fat and bold as sea-raiders, but easily lured with a pinch of bread, though no one liked eating them much. So the thought of drink cheered everyone except me, who had to ask where he had got a fistful of silver. Brother John shrugged.

‘The church, lad. God provides.’

‘What church?’

The little priest waved a hand vaguely in the general direction of Iceland. ‘It was a well-established place,’ he added, ‘well patronised. By the well-off. A well of infinite substance …’

‘You’ve been cutting purses again, holy man,’ growled Kvasir.

Brother John caught my eye and shrugged. ‘One only. A truly upholstered worshipper, who could afford it. Radix omnium malorum est cupiditas, after all.’

‘I wish you’d stop chewing in that Latin,’ growled Kvasir, ‘as if we all knew what you say. Orm, what’s he say?’

‘He says sense,’ I said. ‘Love of money is the root of all evil.’

Kvasir grunted, shaking his head disapprovingly, but smiling all the same. Brother John had no mirth in him at all when he met my eyes.

‘We need it, lad,’ he said quietly and I felt the annoyance and anger drain from me. He was right: warmth and drink and a chance to plan, that was what we needed, but cutting purses was bad enough without doing it in a church. And him being a heretic to the Great City’s Christ-men was buttering the stockfish too thick all round. All of which I mentioned in passing as we headed for the Dolphin.

‘It isn’t a church to me, Orm lad,’ he chuckled, his curls plastered to his forehead. ‘It’s an eggshell of stone, no more, a fragile thing built to look strong. There is no hinge of the Lord here. God will sweep it away in His own good time but, until then, per scelus semper tutum est sceleribus iter.’

Crime’s safest course is through more crime. I laughed, for all the sick bitterness in me. He reminded me of Illugi, the Oathsworn’s Odin godi, but that Aesir priest had gone mad and died in Atil’s howe along with Einar and others, leaving me as jarl and godi both, with neither wit nor wisdom for either.

But, because of Brother John, we were all declared Christ-men now, dipped in holy water and sworn such – prime-signed, as they say – though the crucifixes hung round our necks all looked like Thor hammers and I did not feel that the power of our Odin-oath had diminished any, which had been my reasoning for embracing the Christ in the first place.

The Dolphin nestled in the lee of Septimus Severus’s wall and looked as old. It had a floor of tiles, fine as any palace, but the walls were roughly plastered and the smoking iron lanterns hung so low you had to duck between them.

It was noisy and dim with fug and crowded with people, rank with sweat and grease and cooking and, just for one blade-bright moment, I was back in Bjornshafen, hugging the hearthfire’s red-gold warmth, listening to the wind whistle its way into the Snaefel forests, pausing only to judder the beams and flap the partition hangings, so that they sounded like wings in the dark.

Heimthra, the longing for home, for the way things had been.

But this was a hall where strangers did not rise to greet you, as was proper and polite, but carried on eating and ignoring you. This was a hall where folk ate reclining and sitting upright at a bench marked you at once as inferior, yet another strangeness in a city full of wonders, like the ornate basins which existed for no other reason than to throw water into the air for the spectator’s enjoyment.

The reason I liked the taberna was because it was full of familiar voices: Greeks and Slavs and traders from further north all talking in a maelstrom of different tongues, all with one subject: how the river trade was a dangerous business now that Sviatoslav, Great Prince of the Rus, had decided to fight both the Khazars and the Volga Bulgars.

It seemed that the Prince of the Rus had gone mad after the fall of the Khazar city of Sarkel, down on the Dark Sea – which event the Oathsworn had attended, after a fashion. He was now headed off to the Khazar capital, Itil on the Caspian, to finish them off, but hadn’t even waited for that before sending men further north to annoy the Volga Bulgars.

‘He’s like a drunk in a hall, stumbling over feet and wanting to fight all those he falls on. What was he thinking?’ demanded Drozd, a Slav trader we knew slightly and a man fitted perfectly to his name – Thrush – being beady-eyed and quick in his head movements.

‘He wasn’t thinking at all, it seems to me,’ another said. ‘Next you know, he will think he can take on the Great City.’

‘Pity on him if he does, right enough,’ Radoslav agreed, ‘for that means hard war and the Miklagard Handshake.’

That I had never heard of and said as much. Radoslav’s mouth widened in a grin like a steel trap and he laughed, causing his brow-braid to dip in his leather mug.

‘They offer a wrist-grasp of peace, but that is only to hold you close, by the sword-arm,’ he told us, sucking ale off the wet end of his hair. ‘The dagger is in the other.’

‘Let’s hope he does and dies for his foolishness. Maybe then we can go back north,’ Finn said, blowing froth off his straggling moustache.

I said nothing. The truth was that we could never go north, even if Sviatoslav turned his face to the wall tomorrow. He had three sons who would squabble over their inheritance and we had annoyed them all in the hunt for Attila’s hoard out on the steppe – the secret of which now lurked under Starkad’s fingertips.

He did not know, I was sure. Almost sure. He took the sword from me because Choniates the merchant had valued it and had probably offered highly for it. Even Choniates did not know what the scratches on the handle meant, but he knew how fine the blade was and where it had come from. Even if Starkad read runes well, he would make no sense of the ones on the sword’s grip.

Perhaps they even thought the rune serpent, carved into the steel when it was made, held the secret of the way to Atil’s tomb – and perhaps it did, for no one could read that spell in full, not even Illugi Godi when he was alive and he was a man who knew his runes. I had my own idea about what those runes did, all the same, and felt a chill of fear at not having the sword. Would all my hurts and ills come back in a rush now, no longer held at bay by that snake-knot spell?

Finn only nodded when I whispered all this out, eyeing me scornfully when I came to the last part, for he and Kvasir were the only ones I had shared this with and neither of them believed my good health and wound-luck was anything other than youth and Odin’s favour.

For a while Finn sat moodily stroking the beard he had plaited into what looked like black leather straps, trying to ignore the woman yelling at him from the other side of the hall.

‘She wants you, does Elli,’ Kvasir pointed out. ‘The gods know why – sorry, Brother John, God knows why.’

‘You’ll be well in there, with no silver changing hands at all,’ Sighvat added moodily.

Finn stirred uncomfortably. ‘I know. I have no joy in me for it this night.’

‘It’s the name,’ declared Sighvat and that, together with Finn’s half-ashamed scowl, managed a laugh from us. Elli, according to the old saga tales – and we had no reason to disbelieve them, Christ-sworn or no – was the giant crone who had wrestled with Thor, the one who was really Old Age.

I could see where that could be … diminishing to a man of sensitive nature. I said as much and Finn drained his mug, slapped it angrily on the table and lurched off to the whore, looking to soak his black rage in the white light of sweaty humping.

I sat back, easing. Brother John was right; we had all needed this. Now … it was clear Starkad was working for Architos Choniates, the merchant. We needed to—

Then, of course, Odin’s curse kicked in the door.

Well, Short Eldgrim did, slamming through in a hiss of damp wind and curses from those nearest as it washed them, swirling the lantern smoke. He spotted me, bustled his way through and sat, breathing heavily, the network of scars on his face made whiter by its weather-red. ‘Starkad,’ he growled. ‘He’s coming up the street with men at his back.’

‘That’s useful,’ muttered Kvasir. ‘I want to see his face when he finds out he has picked the last drinking place in the world he wants to be in.’

‘One!’ roared the crowd behind us. Elli was showing how many silver coins she could stick on the sweat of her bared breasts. Kvasir grinned. ‘She cheats – she uses honey. I tasted it once.’

‘Pass the word,’ I said softly. Odin’s hand, for sure – I knew One Eye would not let that sword fly from us so lightly, that he had walked the thief right into our clutches.

‘Three!’ Elli was doing well behind us.

Short Eldgrim nodded and slid away. Behind us, a coin slid from Elli’s ample, sweaty charms and the crowd roared. Brother John swallowed ale and narrowed his eyes.

‘A dangerous place to confront him,’ he said, looking round at the crowd.

‘Odin chooses,’ I said flatly and he glanced at me, who was now, supposedly, a prime-signed Christ-follower.

‘Amare et sapere vix deo conciditur’ he said wryly and I had felt my face flush. Even a god finds it hard to love and be wise at the same time; I wondered, after, if our little Christ priest had the power of scrying.

‘I hope that is Roman for “kill them all and let Christ Jesus sort them out”, little man,’ Finn growled, for he hated folk talking in tongues he did not understand. Since he did not understand any other than west Norse, he was frequently red in the face. Someone bumped him and he rounded savagely, slamming the man with an elbow. For a moment, it looked like trouble, but the man saw who it was and backed off, hands held up, aghast at having offended the Oathsworn. Skythians, they called us, or Franks – those who knew a little more used Varangi – and they knew if you took on one, you took on all.

Then the man himself came in, shoving through the door, pausing in a way that let me know, at once, that it was no accident, his arrival in the Dolphin. Heads turned to look; conversation died and silence drifted in with the cold rainwind at the sight of him and the two behind him, openly armed, wearing mail and helms. That only revealed that Starkad and his crew had a powerful new friend in the Great City.

‘Starkad,’ I said and it was like the slap of a blade on the table. Silence fell, voices ceased one by one when they heard their own echo and heads turned as people sensed the hackle-rise tension that had crept into the fug and lantern smoke. Finn’s scowl threatened to split his brow and he growled. Radoslav looked quizzically from one to the other and, even in that moment, I saw the merchant in him, setting us in scales and balancing our enemies on the other pan to see who was worth more.

Starkad was splendid, I had to allow. He was still handsome, but pared away, as if some fire had melted the sleek from him, leaving him wolf-lean, with eyes sunk deep and cheekbones that threatened to break through the skin.

Wound fever, I thought, seeing how bad his limp was – Einar had given him a sore mark, right enough, that day on a hill in the Finns’ land. The Norns’ weave is a strange pattern: Einar was now dead and Starkad was standing there in a red tunic, blue wool breeks, a fine, fur-lined cloak fastened with an expensive pin and a silver jarl torc round his neck. He was, it seemed, making sure I knew his worth.

‘So, Orm Ruriksson,’ he said. There was a shifting round me, the little sucking-kiss sound of eating knives coming out of sheaths. I placed my hands flat on the table. He had two others at his back – one with squint eyes – but I knew there would be more outside, ready to rush to his aid.

‘Starkad Ragnarsson,’ I acknowledged – then froze, for he was wearing a sword at his side and he and his men had dared swagger through Miklagard with weapons openly, which fact had to be considered.

Not just any sword. My sword. The rune-serpent blade he had stolen.

He saw that I had spotted it. He had a smile like the curve of that blade and, behind me, I felt the heat and the stir and heard the low rumble of a growl. Finn.

‘I have heard of the death of Einar,’ Starkad said, making no effort to come closer. ‘A pity, for I owed him a blow.’

‘Consider it Odin luck, since he would have balanced you up with a stroke to the other leg if you had met again,’ I replied evenly, the blood thundering in my ears, ringing out the question of how he came to be wearing that sword. Had he stolen it from Choniates, too? Had the Greek given it to him – if so, why?

Starkad flushed. ‘You yap well for a small pup. But you are running with bigger hounds now.’

‘Just so,’ I answered. This was easy work, for Starkad was not the sharpest adze in the shipyard for wordplay. ‘Since we are speaking of dogs – have you been back to sniff Bluetooth’s arse? Does that King know that you have lost both the fine ships he gave you? No, I didn’t think so. I am thinking he may not stroke your belly, no matter how well you roll on your back at his feet.’

The flush deepened and he laid one hand casually on the hilt of the sabre by way of reply. He saw me stiffen and thought it recognition of the blade and smiled again, recovering. In truth, it was the sight of his pale fingers, like the legs of a spider, sliding along the marks I had made on the hilt, watching them unconsciously trace the scratches, all unknowing.

‘Look …’ began the tavern-owner, his hands trembling as he wiped them over and over on his apron. ‘I want no trouble here …’

‘Then fasten yer hole shut,’ growled the squint-eyed man, his affliction adding to the savagery of his tongue. The tavern-owner winced and backed off. I saw little Drozd sidle away from us, as though we had plague.

‘King Harald can spare two such ships,’ Starkad went on dismissively. ‘I have been tasked with something and will travel to the edge of the world to obey my King.’

I mock-sighed and waved an airy jarl hand at a seat, as if in invitation to discuss this matter that troubled him. I hoped to get him closer, away from the door and the men at his back and the ones I was sure were outside. There would be a fight and blood, since they had weapons and we did not and that would bring the authority of the Great City down on us, but still …

He was polished as a marble step and no fool. ‘You are not what I seek, boy,’ he said with a sneer that refused my invitation. ‘Nor any of these who treat you like a ring-giver on a gifthrone, for all that you have neither seat, nor neck ring, nor even ship to mark you. No sword, either, since I took it.’

He drew back a little from his hate then and forced a smile into my face, which I knew was pale and stricken. I felt the Oathsworn behind me, trembling like ale at an over-full brim and Finn, quivering, barely leashed, finally snapped his bonds.

A bench went over with a clatter and he howled himself forward at Starkad, who whipped that sabre out with a hiss of sound, fast as the flick of an adder’s tongue. Finn, with nothing but his fists, came up two foot short of Starkad’s face, with the point of the rune-serpent sword at his neck. Someone squealed; Elli, I thought dully.

I held up my hand and leashed the others, which act gave me a measure of stone-smoothness, for Starkad noted that and was impressed, despite himself. I could hardly breathe; I wondered if he knew how deadly that blade against Finn’s neck truly was. Even just resting it left a thin, red line. For his part, Finn had froth at the edges of his mouth and I knew that one more comment and he would run his neck up the blade, just to get his hands round Starkad’s own.

‘I have heard tales of this blade,’ Starkad said softly. ‘It cut an anvil, I hear.’

‘Just so,’ I agreed, dry-mouthed. ‘Perhaps, Finn, you should come and sit by me. Your head is hard, but not harder than the anvil that blade was forged on.’

The rigid line of Finn softened a little and he took a step backward, away from the blade. Each step laboured, he unreeled from the hook of that runesword. I breathed. Starkad, smirking, waited until Finn was seated, then sheathed the weapon; life flooded back to the room with a breathy sigh.

‘You have the look of a jarl,’ I said into Starkad’s smirk, my chest still tight with the fear of what might just have happened, ‘but you should beware the jarl’s torc.’

‘You should only beware it when you do not have it,’ Starkad spat back. ‘The mark of ringmoney is the mark of a gift-giver, whom men follow.’

I said nothing to that, for Gunnar Raudi – my true father – had often told me that you should never interrupt an enemy who was making a mistake. I already knew the secret of the jarl torc Starkad was so proud of wearing. It was just a neck ring of silver, which we still call ringmoney, whose dragonhead ends snarl at one another on your chest.

The secret was that the real one was made of steel, carried by the men who wielded it for you. It hung round your neck, another kind of rune serpent, at once an ornament of greatness and a cursed weight that could drag you to your knees and which you could not take off in life.

I knew that from Einar, who had warned me of it as he died by my hand, sitting on Attila’s throne. Now I felt the weight of it myself – even though I could not, as Starkad had seen, afford a real one.

‘I seek the priest, one Martin, the monk from Hammaburg,’ Starkad went on. ‘You know where he is, I am thinking.’

I was silent, knowing exactly what it was Starkad sought. Not a silver hoard at all, but Martin’s treasure, the remains of his Christ spear, the one stuck in the side of the White Christ as he hung on the cross and whose iron head had helped make the sabre Starkad now wore. He did not know that and I leached a little comfort from the secret.

Now that King Harald Bluetooth was a Christ-man himself, he fancied this god spear to help make everyone in his kingdom stronger in the Christ faith – no matter that the Basileus of the Romans claimed such a spear already resided in the Great City. Like me, Bluetooth believed Martin had the real one.

‘He fled,’ Starkad added, when my silence stretched too far. ‘The monk fled. To here, I am thinking, and to you, since you are the only ones he knows.’

It was a good thought, for Martin had been with us for long enough, but Starkad did not know that it was not as a friend. My tongue was already forming the words to tell him this when the thought came to me that we could not – dare not – take him here. It was certain that the Watch had already been called and Starkad was measuring his time like a shipmaster tallies his distances, down to the last eyeflick.

Miklagard was a haven for Starkad; he had to be lured out of it.

‘East,’ I said. ‘To Serkland and Jorsalir, his holy city.’

I have my own thoughts on who made me gold-browed at that moment, to come up with a lie and the wit to speak it with such shrugging smoothness. Like all Odin’s gifts it was double-edged.

He blinked at the ease with which I had given up the information and you could see him weigh it like a new coin and wonder if it rang true when you dropped it on a table. I felt the others twitch, though, those who knew it to be a lie, or suspected the same. I hoped Starkad did not look in their bewildered eyes.

In the end, he bit the coin of it and decided it was gold. ‘Let this be an end of things between us, then. Einar is dead and I have no more quarrel with the Oathsworn.’

‘Return the sword you stole and I will consider it,’ I told him. ‘I once thought you a wolf, Starkad, but it turns out you are no more than an alley dog.’

He had the grace to redden at that. ‘I took the sword the same way you took my drakkar – because I could and it was needful,’ he replied, narrow-eyed with hate. ‘It stays with me because you and your Oathsworn pack cost me dear and I will count it bloodprice for the losses.’

‘Not the last losses you will have,’ Kvasir interrupted angrily. ‘We are not finished with you – take care to keep beyond reach of my blade, Starkad Ragnarsson.’

‘What blade?’ sneered Starkad and slapped his side. ‘I have the only true blade you nithings owned.’

The door opened in a blast of wind and rain and a head hissed urgently at Starkad’s back. It did not take much to know the Watch was coming up the street. Starkad leaned forward at the hip a little and his lip curled.

‘I know you, Kvasir, and you, Finn Horsehead. You also, boy Bear Slayer. I will find out the truth of what you say. If you spoke me false here, or if you get in my way, I will make you all unwind your guts round a pole until you die.’

He backed out of the door while I was still blinking at the picture he had placed in my head with that last one, for I had heard of this cruel trick.

There was a surge, like a wave breaking on a skerry, and I hammered the table to bring the Oathsworn up short, while the others in the tavern scrambled to be out and away. Finn hurled one luckless chariot-racing fan sideways, then stopped, sullen as winter haar.

‘We have to kill Starkad,’ he growled, sitting. ‘Slowly.’

‘Is this sword so valuable, then?’ asked Radoslav. ‘And who is this priest?’

I told him.

‘What holy icon?’ demanded Brother John when he heard my brief tale of Martin and his spear.

‘A spear, like Odin’s Gungnir, only a Roman one,’ I answered. ‘The one they stuck in the Christ when he hung on the cross. Only the metal end is missing from it.’

Brother John’s mouth hung open like the hood of a cloak, so I did not mention that the metal end had been used in the making of the runed sabre Starkad had stolen to feed the greed-fire of Architos Choniates. I did not understand why Starkad had the sword, all the same.

‘Another Holy Lance?’ Brother John was a flail of scorn. ‘The Greeks-who-are-Romans here swear they have one, tucked up in a special palace with Christ’s bed linen and sandals.’

I shrugged. Brother John snorted his disgust and added, scornfully, ‘Mundus vult decipi.’

The world wants to be deceived … I wasn’t sure if it was a judgement on Martin’s desires or on just how genuine the spear was. But Brother John was silent after that, deep in thought.

‘Concerning this sword …’ Radoslav began, but the Watch piled in then and the tavern-owner went off into an arm-wave of Greek. There were looks at us, then back again, then at us.

Eventually, the Watch commander, black-bearded and banded in leather, peeled off his dripping helmet, tucked it in the crook of his arm, sighed and came towards us. His men eyed us warily, their iron-tipped staffs ready.

‘Who leads?’ he asked, which let me know he was no stranger to our kind. When I stood up, he blinked a bit, for he had been looking expectantly at Finn, who now showed him a deal of sarcastic teeth.

‘Right,’ said the Watch commander and jerked a thumb back at the tavern-owner. ‘Not your fault, Ziphas says, but he still thinks you brought armed men to his place. Scared off his custom. Neither am I happy with the idea of you lot blood-feuding on my patch. So beat it. Consider it lucky you have no weapons yourselves, else I would have you in the Stinking Dark.’

We knew of that prison and it was as bad as it sounded. Finn growled but the Watch commander was grizzled enough to have seen it all and simply shook his head wearily and wandered off, wiping the rain from his face. Ziphas, the tavern-owner, still smearing his hands on his apron, finally left it alone and spread them, shrugging.

‘Maybe a week, eh?’ he said apologetically. ‘Let folk forget. If they see you here tomorrow, they will not stay – and you don’t spend enough to make up the difference.’

We left, meek as lambs, though Finn was growling about how shaming it was for a good man from the North to be sent packing by a Greek in an apron.

‘We should follow Starkad now,’ Short Eldgrim growled. ‘Take him.’

Finn Horsehead growled his agreement, but Kvasir, as we shrugged and shook the rain off back in our warehouse, pointed out the obvious.

‘I am thinking Starkad’s crew are now hired men and so permitted weapons,’ he observed. ‘Choniates will stand surety for them here like a jarl.’

Radoslav cleared his throat, cautious about adding his weight to what was, after all, not much of his business. ‘You should be aware that this Starkad, if he is Choniates’ hired man, has the right of it under law. We will have warriors from the city on us, too, if blood is shed and not just the Watch with their sticks. Real soldiers.’

‘We?’ I asked and he grinned that bear-trap grin.

‘It is a mark of my clan that when you save a man’s life you are bound to keep helping him,’ he declared. ‘Anyway, I want to see this wonderful sword called Rune Serpent.’

I thought to correct him, then shrugged. It was as good a name for that marked sabre as any – and it was how we got it back that mattered.

‘Which brings up another question,’ said Gizur Gydasson. ‘What was all that cow guff about the monk going to Serkland? Has he really gone there?’

That hung in the air like a waiting hawk.

‘If force will not do it, then cunning must,’ Brother John said before I could answer, and I saw he had worked it out. ‘Magister artis ingeniique largitor venter.’

‘Dofni bacraut,’ Finn growled. ‘What does that mean?’

‘It means, you ignorant sow’s ear, that ingenuity triumphs in the face of adversity.’

Finn grinned. ‘Why didn’t you say that, then?’

‘Because I am a man of learning,’ Brother John gave back amiably. ‘And if you call me a stupid arsehole again – in any language – I will make your head ring.’

Everyone laughed as Finn scowled at the fierce little Christ priest, but no one was much the wiser until I turned to Short Eldgrim and told him to find Starkad and watch him. Then I turned to Radoslav and asked him about his ship. Eyes brightened and shoulders went back, for then they saw it: Starkad would set off after Martin and we would follow, trusting in skill and the gods, as we had done so many times before.

Anything can happen on the whale road.